1302 Lessons from the Big House

Linda Rogers reviews two books:

Indian in the Cabinet: Speaking Truth to Power

by Jody Wilson-Raybould

Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2021

$34.99 / 9781443465366

*

From Where I Stand: Rebuilding Indigenous Nations for a Stronger Canada

by Jody Wilson-Raybould

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019

$24.95 / 9780774880534

*

CHARACTER, a drama with some bad actors and some good ones.

CHARACTER, a drama with some bad actors and some good ones.

Jody Wilson-Raybould’s blueprint for a life of service is laid out in From Where I Stand, her collection of speeches on the state of the nation in the tragic wake of the Indian Act, a legal justification of cultural genocide. Her mission is to remediate the damage done to her people and heal the country, no small task.

She makes it clear from her intent to her actions that her model of governance is as old as her Kwakwaka’wakw heritage. It is about balance.

I was taught that equilibrium is necessary in society and must be maintained by adherence to our laws, practices, and customs, including those of the Bighouse. When the balance is upset, institutions must seek to find and reset it. I believe this is true for this country as a whole, that it is only by embracing diversity and promoting a truly inclusive society that we can restore and maintain balance in Canada.

She had every reason to believe her position was respected, because that is her training and heritage. Not only does she know the rules of conduct, she has also studied the laws of the land, many of which have been perverted to oppress the original people who had already evolved an effective and fair system of governance by and for the people.

The story of this ongoing narrative is of a cultural bridge disrespected in bias against gender and culture and, with her, all of us ingenuous in our optimism, we feel the tragic loss of an opportunity squandered.

The emotional impact of her examination of the social contract is to at once understand she was a sheep led to slaughter by her faith in the principles of justice, albeit wearing a fleece of asbestos armour in the bonfire of vanities, Trudeau style ( as opposed to substance) post-liberalism. Because her desiderata for governance are based in idealism and an inherited ethic, there is strength in her analysis of current events and promise in her continued presence in public life, as she notes: “…we will, indeed, continue to collectively breathe life into our Constitution and in so doing set the standard for the globe in terms of freedoms and rights and the protection of equality for all.”

*

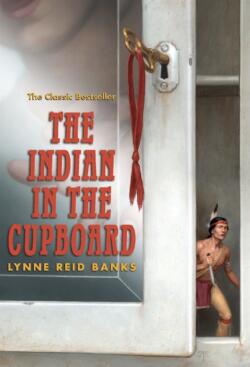

The second book reviewed here, Indian in the Cabinet, the story of her use and abuse in the corridors of power, is the unmasking of our mutual fantasy, its title wry commentary on a book by Lynne Reid Banks, The Indian in the Cupboard, that Raybould-Wilson must have read as a child. It doesn’t take long for its protagonist and storyteller to communicate that she too was miscast, a toy used to facilitate fiction, the fairy tale that the very government applying the reprehensible Indian Act to control the most vicious chapter in our collective experience actually has the moral character to change the narrative.

The second book reviewed here, Indian in the Cabinet, the story of her use and abuse in the corridors of power, is the unmasking of our mutual fantasy, its title wry commentary on a book by Lynne Reid Banks, The Indian in the Cupboard, that Raybould-Wilson must have read as a child. It doesn’t take long for its protagonist and storyteller to communicate that she too was miscast, a toy used to facilitate fiction, the fairy tale that the very government applying the reprehensible Indian Act to control the most vicious chapter in our collective experience actually has the moral character to change the narrative.

These books are about character, the treasure generations of matriarchs passed down to their daughters and what happens when it is undermined by a patriarchy running on money and power.

Wilson-Raybould introduces herself as a woman with a dream, the belief that she could use her understanding of a colonial legal system to disturb the verbs that have only served to “legally” oppress her people since its implementation, that in government she could facilitate change in our egregious history of suppression.

It is a charming introduction as she begins her dance with the master manipulator, a pretty face painted by alliances that remain unchanged as the past continues to dictate the present in spite of lofty rhetoric to the contrary.

The plot is familiar. As usual, power corrupts.

There is a saying about politicians running with poetry and ruling with prose, the dull thud of ideals landing in mud, defining the difference between sweet music and the sour disposition of power.

What lawyers and poets share is comprehension of the importance of semantics. The brief seduction of this female lawyer and Indigenous rights activist mimics that of a country compromised by sunny ways, the blinding promise of shining cities just beyond our reach, as she quickly learned that “Words, in the work of reconciliation, are also cheap without real action — action that goes to the core of undoing the colonial laws, policies, and practices, and that is based on the real meaning of reconciliation.”

What were the inherent ironies when she allowed herself to be embraced by the dream? What did Jody Wilson-Raybould not understand about power and what did the Prime Minister, himself mesmerized by flashbulbs and sound bites, the smell of greasepaint, the roar of the crowd, no grasp about a character formed by generations of women schooled in good governance, rule of the people, the common good.

That is potlatching. When we share what we have, we are all enriched.

Many of us shared her optimism. Would this dynamic person, the inheritor of a battered but not broken matriarchy, be able to effect the change too often described in bold rhetoric and later discarded with the Emperor’s vestments? She hoped. We hoped, even as Mister Sunny Ways threw off his shining raiment and revealed a clown in Punjabi regalia making a mockery of sacred choreography.

In her own words, it was bound to happen. She lists the transgressions of an actor for whom disingenuousness is as easy as slipping into costumes: black face, free rides from the Aga Khan, dress-up in Delhi. She mentions outbursts of temper. Actors get cranky when they struggle to remember their lines.

And who is the ultimate victim of her truth telling? Not Wilson-Raybould as we learn, because she is sidelined but undiminished by the corrupt choreography of her dance with a gilded suit controlled by puppeteers.

The Emperor turns out to be ugly, covered in suppurating wounds, scars from dishonest liaisons with industries allied to climate change and whippings from intransigent voters dedicated to maintaining a status quo that has undermined thousands of years of cooperation with the land that sustains us. How ironic the subtle difference between the words “suppurate” and “superate,” almost homonyms, when one is transcendence of the ordinary and the other is a puss bubble, poison built up over centuries of injustice.

How ironic the name of our current Prime Minister, so close to what is right but somehow reduced to “Just in…” the latest sound bite as the drummer calls the dance dictated by breaking news.

Wilson-Raybould came with an agenda and the training and experience to facilitate her mandate, but just as quickly as she got to work on reform, her debt was called in, at first in subtle ways, but then with the blunt force of realisation. The naked emperor removed her from a throne room she never really accessed, as she describes in the rules about parliamentary communication. In one word, don’t. We learn the cabinet is advised not to advise one another.

Is the root word of parliament not conversation, the dialectic that leads to consensus?

“I feared government was slipping back into its old colonial patterns.”

Just as the Prime Minister, acting his part as reformer in chief, was effective in charming her, she mesmerises her readers with her candid, except for classified information, description of her reaction to favour and fall from grace. She reacts as a woman and as an Indigenous person denied her full humanity, giving space to the larger debate about human rights, and we can’t help but respond emotionally to this battering. And then she is treated like a woman, as misogyny reveals itself. This reader needed to take a shower when she closed the book, a common reaction of rape victims washing in the blood of the lamb, or whatever.

When the patriarchy is so dedicated to power that it directs its children to bend over and drink dirty water, what is the justification for its continuance under the shadowy hat of capitalism. Da capo, yes, off with its/his head. Wilson-Raybould is sharpening her knives in these books. She is ready.

First and foremost a woman of her ilk, she was raised in the powerful language of a matriarch who knew that so long as women/ matriarchy is under assault then so is our very connection to the Earth, to the Mother Trees that sustain life, to the Moon in the sky that assists us in navigating our lives. Her struggle is our struggle, the most important ever.

Because Wilson-Raybould is candid in reporting her reactions, we feel every impertinence, every condescension as she experiences exclusion on the very public stage where she had been invited to perform on our behalf. As it happens, she was placed in an alleged power position by the grace and favour of hollow men, suits who follow markets controlled by money and public opinion dominated by manipulative social media. She makes sure we know that, in the end, her situation equated with pin-ups on dart boards.

Her realisation of fraud is stunning and no one can read her account without feeling the threatened penetration of her suit of armour, a grandmother’s wisdom.

This reader recalls letters I received from the Emperor’s mother when she too experienced loss of self in the machinery of the Ottawa establishment. “I can’t be myself.” It is a female epiphany, the realisation that seduction is rape, repeating what happened to Wilson-Raybould’s ancestresses when the Whitecomers arrived.

This is what Kent Monkman brought to his audience in his painting Hanky Panky (2020) for the ritual buggering of a Prime Minister who has broken his promise to First Nations and continued the mandate of the witnesses who began the careful dismantling of its ancient matrilineal cultures, politicians like Sir John A. Macdonald who suffered little children to be stolen and sexually assaulted by the ecclesiastical hypocrites who were his accomplices in crime.

Monkman’s fictional apparatus is a sex toy held up by his alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickles, symbol of the Red Hand movement, meant to halt the rape and murder of Indigenous women. In handing over the power, Monkman’s avatar (male elegance in his Eagle headdress) makes a stunning statement about a status quo which, despite the Indigenous Renaissance, despite treaties and promises, despite general public awareness of inequity and racism, remains unchanged. The Trail of Tears, scrubbing out our calculated identity of Canadian decency, continues to extend through the wilderness into the public domain of our so-called shining cities.

Did the Wizard of Oz really expect an Indigenous buck and wing from Puglaas, the granddaughter of Pugdladee? “Was I supposed to act like Trudeau’s very own Bill Barr and do his bidding?” Not a chance in Hell.

In her feminist speech “Each of Us, in Our Own Way Is a Hiligaxste,” in From Where I Stand, she articulated the responsibility of wise women to effect gender balance. “As in my culture, we have to tame the Hamatsa. Modern democracies require that those who govern are elected to do so for the right reasons and must be held accountable.”

Monkman’s Hanky Panky is shock therapy. That is the function of satire, the catalyst of social change. Trudeau will not easily relinquish his pacts with oligarchs. Beguiled Indigenous girls will not easily give up their contract with the beauty myth, the Cinderella possibility that has made every missing woman poster almost identical, making victim recognition difficult if not impossible. That is our challenge as participants in democracy.

Too often we conform to expectation. That is our historical weakness and the key to transformation. All we need to do is change those expectations in empirical reality. It’s that simple. Wilson-Reybould, despite her trial by fire can still imagine it happening because she intends to recalibrate a world that is out of balance.

She holds a mirror up for us and what we see is a nation shocked out of our comfortable pews. We are not inherently “nice.” Our settlement was far from peaceful, a handshake agreement to redesign a people who already lived with good government and intact morality into clones of their Imperial oppressors. It is time to address wounds that cannot be negotiated scar by scar through civil contracts and redefine ourselves in the deep language of holy laws that transcend politics and religion. It is time to do what is right.

The reflection one sees of oneself in the mirror is the legacy that ultimately matters. I have strived to live a life of principle and values, to reflect the best of what I have been taught is important in life. I keep looking in the mirror as part of the striving, to make sure I am doing my part to honour the past, change the present, and build a stronger future.

Amen, Sister. Gilaskas’la

*

Linda Rogers was the first Public Relations chair of The Status of Women Action Co-ordinating Committee, a politically and culturally diverse coalition of women, including her heroic sister Rosemary Brown. Rogers is the editor of the Mother, the Verb, the Swan Sister Treasure Book, which celebrates resistance to paternalism in Kwakawaka’wakw’ culture and world community. Editor’s note: Linda Rogers has recently reviewed books by Carol Shields & Nora Foster Stovel, Mandi Em, Sue Goyette, Cid V. Brunet, Betsy Warland, Yvonne Owens, Junie Désil, Rob Taylor, Andrea Actis, Grace Lau, Janet Gallant & Sharon Thesen, Philip Resnick, Celeste Nazeli Snowber, Patrick Friesen, Stephen Collis, Colin Browne, and Heidi Greco for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “1302 Lessons from the Big House”

Totally agree with Mahnoud Ali. This is less a review than Rogers primping herself in front of some imaginary mirror.

I am going to be on a Zoom meeting to discuss Indian in the Cabinet, so I wanted to see what the book reviews said. I find this an emotional diatribe replete with a grab bag of righteous terminology that is, in effect, devoid of any meaning.

Wow!

Linda Rogers says she’ll be sure to cover her mirror next time she begins an emotional diatribe , observations based on a lifetime of scholarship and advocacy. And she won’t be joining a political party anytime soon.