1295 Chapman’s high-rise history

Vancouver Vice: Crime and Spectacle in the City’s West End

by Aaron Chapman

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021

$27.95 / 9781551528694

Reviewed by Grahame Ware

*

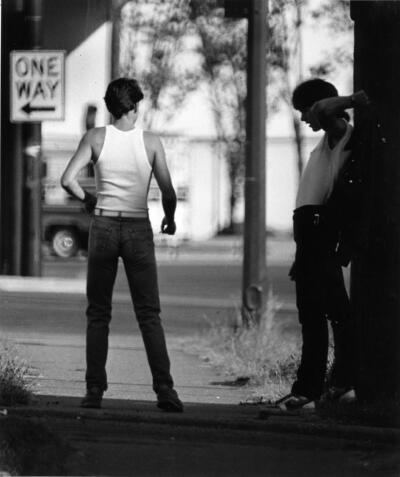

Aaron Chapman begins Vancouver Vice by using the West End Sex Workers Memorial (dedicated in 2016) as a point of reference and meditation regarding the whole dynamics of sexual freedom in all of its manifestations. Then, using 1970s sexual liberation, revolution, and sex worker trade of the West End as a proxy, Chapman carefully chisels and carves a bas-relief of Vancouveriana that depicts its depth and breadth but also places it deftly within the context of North America. In Vancouver Vice: Crime and Spectacle in the City’s West End, Chapman’s voice resonates with a mature lyricism, fearlessly bringing to bear many stories and scenes that illuminate the whole zeitgeist. This is no mean feat when one considers all the things that were going on in the seventies and eighties. I daresay, too, that no one has ever captured it quite like Chapman, whose tone and timbre throughout the book is consistently engaging and effortlessly authoritative.

Aaron Chapman begins Vancouver Vice by using the West End Sex Workers Memorial (dedicated in 2016) as a point of reference and meditation regarding the whole dynamics of sexual freedom in all of its manifestations. Then, using 1970s sexual liberation, revolution, and sex worker trade of the West End as a proxy, Chapman carefully chisels and carves a bas-relief of Vancouveriana that depicts its depth and breadth but also places it deftly within the context of North America. In Vancouver Vice: Crime and Spectacle in the City’s West End, Chapman’s voice resonates with a mature lyricism, fearlessly bringing to bear many stories and scenes that illuminate the whole zeitgeist. This is no mean feat when one considers all the things that were going on in the seventies and eighties. I daresay, too, that no one has ever captured it quite like Chapman, whose tone and timbre throughout the book is consistently engaging and effortlessly authoritative.

Chapman’s sure voice relates the city’s history in a smooth and accessible way. “It was as if Vancouver had decided to sow as much of its wild oats as fast as it could — exorcise all of its urban demons — before the city got together for the Expo 86 ‘family photo,’ the world exposition that would transform and define the city for the years that followed” (p. 15).

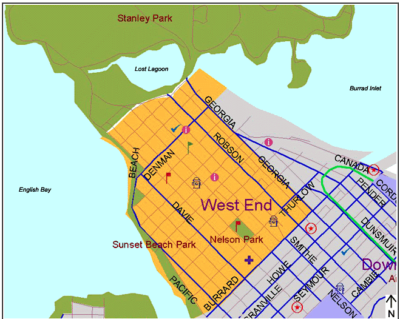

Chapman lays down the foundational history of Vancouver’s West End, brick by sociological brick until he himself builds his own high-rise of a book that gazes across the social landscape of the time with a transcendent omniscience. “Beyond the boundaries of the West End,” notes Chapman, “with so many new arrivals to Vancouver expanding the population of the city, there are many who have little to no knowledge of the neighbourhood’s tumultuous recent history” (p. 11).

Vancouver’s urban historians have been slow to document and portray this era. “Too many in this chapter of the city’s history have passed on before their time, unable to tell their own story. Many seem to have vanished from memory; others will never been forgotten. And while some former sex workers who once walked the streets of the West End celebrate an era that they feel was less compromised by exploitation, there are others whose experiences were not as fortunate” (p. 15).

Precipitating much of the change in the West End and, indeed, Vancouver itself was the huge increase in population. The density soared with the building of high-rise apartments:

High-rises were the next big change in the West End. In a thirteen-year run, from 1959 to 1972, developers built more than 220 high-rise apartment buildings, several of them more than twenty storeys. These new towering apartment complexes provided convenient housing for the ever-expanding workforce as jobs proliferated in the growing downtown corporate sector. A flood of secretaries, salespeople, flight attendants, nightclub performers, and hairdressers began to populate the neighbourhood…. None of the architects who designed these towers would probably have imagined it, but the high-rises filled with a new kind of modern Vancouverite: the swinging single. Thousands of young, professional, single West Enders now mixed everywhere from the laundry room to the beach to the bedroom (pp. 20-21).

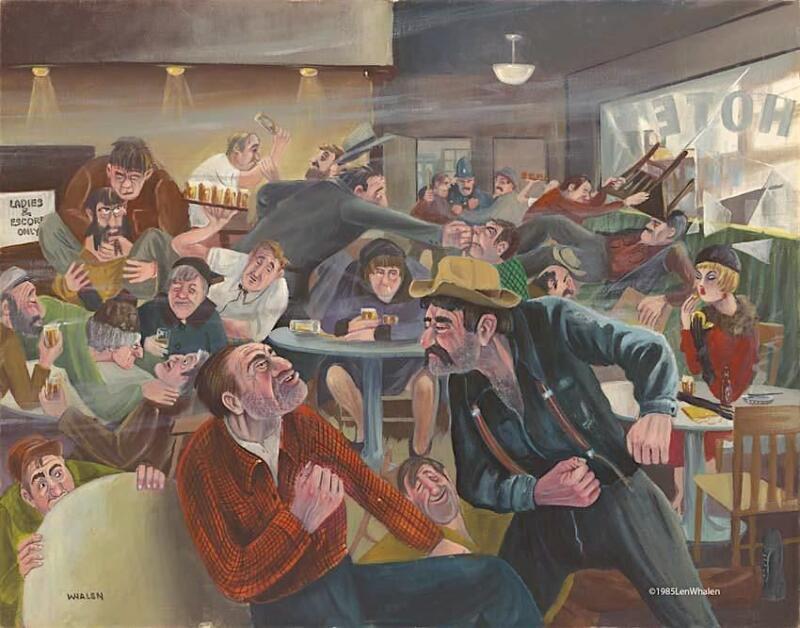

Nearby Gastown was just starting to blossom in 1973-74 but, as I can attest, there were still some old hangouts that resisted gentrification, especially hotel beer parlous such as the Anchor. I worked with an old guy called Austin Taylor who actually lived in the Anchor Hotel at 90 Alexander Street. “Ozzie” didn’t eat a lot and his idea of food was to put some tomato juice in his beer. He was a tough old bird who had been a logger for a good part of his early life. He was part of that generation of loggers that once out of the woods and back in town, whooped it up in their Zoot suits with some babes, shot a little smack and then went back to the woods to get straight. Now, for Ozzie, it was all about booze. He used to chide me for being so young and married. As a bachelor, his favourite expression was, “It’s a dirty old duck that swims in the same old pond.”

I spent one Saturday night at the Anchor in the company of Ozzie and that was enough for me — and why Chapman’s description of the Anchor rang true as a bell: “Day and night, drinkers, drug dealers, drug users, sex workers, and even what Robson describes as a group of “Maoist hippies” all held court in the bar. Police doing casual checks in the bar even had bottles thrown at them and management did little to discourage this behaviour.”

And Chapman continues:

The bar was full, but they [VPD detectives] found this gal there with about thirty vials of liquid hash in her purse, selling it out of the place like it was a garage sale on a Sunday afternoon. With that much, we had to take her in. So Rick [Stevens] grabbed her for the arrest, and she started fighting. The next thing you know, the whole place went nuts and turned on us. What started as pushing and shoving broke into a full-blown mêlée. Tables were overturned. Beer bottles and smashed glass rained down on the heads of Detectives Robson, Stevens, and Brown. With the woman in tow, they retreated to the back wall of the Anchor and (then) into the toilets, radioing for backup.“Ronnie [Brown] pulled his gun and yelled that the first person who tried to come in would get his brains blown out,” Robson recalls. “I had my foot up against the door as they were just thumping away (p. 49).

Ah yes, the “pigs” were not popular back then especially at the rowdy Anchor. In the gentrification of Gastown, the Anchor had a new neighbour right next to it — the newly opened restaurant, La Crêperie. The patrons nicknamed it Creepies. That’s just the kind of folks they were. Nothing was going to change them.

But, of course, the focus of the book is to record the West End and some of the more skanky and, indeed, pathologically criminal things that went down. This doesn’t make for a dark tale by any means. Chapman is not attempting anything like an exploitative or voyeuristic pulp fiction. He is, after all, an historian and to this end he evenly lays out a number of events that stitch together a realistic and fantastic book.

Overall, Vancouver Vice is a wise and balanced portrait of the phenomena of sexual liberation, sexploitation, and repressive politics in the West End in the seventies and eighties where, inevitably, elements of crime rose up to tarnish the ideals and lives of many people and players in that drama. Chapman, who tracked down and interviewed many retired detectives, filters and integrates their recollections seamlessly and compellingly into a grand narrative.

This enjoyable and informative book adds to Chapman’s already impressive canon of recent award-winning Vancouveriana social history. Full credit to his team at Arsenal Pulp Press. I can’t see how this publication won’t merit another BC Book Prize nomination. Get it for yourself and get it for Christmas gifts. This is one helluva book for your Vancouver and BC history bookshelves.

*

Grahame Ware has been a regular contributor to The Ormsby Review since its inception. As well as book reviews, he has contributed four memoirs, The Sonics at the Grooveyard, On the road with Sir Kenneth, My Private Italy, and My Private Chinatown. He is a member of the SFU-based Canadian Association of Independent Scholars. Grahame lives on Gabriola Island where he is finishing a book on Jim Christie, a Scottish social activist in the nineteenth century Okanagan Valley. He also makes wooden sculpture from forest refugees and driftwood detritus. Editor’s note: Grahame Ware has also reviewed books by Ira Nadel, Aaron Chapman (Vancouver After Dark), John Moore, Ken Smedley, Mike Lascelle, Roy Miki/ Michael Barnholden, Pirjo Raits, Keith McKellar (Laughing Hand), Lou McKee, Monika Ullmann, Kerri Sakamoto, Jan DeGrass, Jon Steinman, and Dan Jason & Michele Genest for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1295 Chapman’s high-rise history”

Pre-ordered!

Many thanks to Grahame Ware and the Ormsby Review for the kind words on the book.