1252 J.W. McKay & the Métis mystery

Joseph William McKay: A Métis Business Leader in Colonial British Columbia

by Greg N. Fraser

Victoria: Heritage House, 2021

$22.95 / 9781772033403

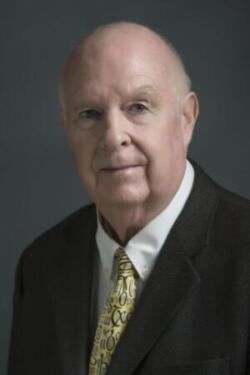

Reviewed by John R. Hinde

*

By coincidence, Greg N. Fraser’s biography, Joseph William McKay: A Métis Business Leader in Colonial British Columbia, arrived on my desk the same day that the Tk’emlups te Secwépemc First Nation confirmed to the world the presence of about 200 unmarked graves, mostly of children, at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. This was followed by revelations from the Brandon First Nation and from the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan, where 751 unmarked graves were confirmed. This was only the beginning and many more similar announcements from First Nations across the country have since been made.

By coincidence, Greg N. Fraser’s biography, Joseph William McKay: A Métis Business Leader in Colonial British Columbia, arrived on my desk the same day that the Tk’emlups te Secwépemc First Nation confirmed to the world the presence of about 200 unmarked graves, mostly of children, at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. This was followed by revelations from the Brandon First Nation and from the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan, where 751 unmarked graves were confirmed. This was only the beginning and many more similar announcements from First Nations across the country have since been made.

As it happens, Joseph William McKay (1829-1900) was serving as the Canadian federal government’s Indian Agent for Kamloops and Okanagan when the precursor of the Kamloops Indian Residential School, the Kamloops Industrial School, was established in 1890. McKay’s active role in organizing the school was recognized by its principal, Father Alphonse-Marie Carion, (p. 136), whose task it was “to civilize the Indians” through Catholic moral and religious education. Although Greg Fraser is well aware of the destructive nature of the Residential School system and Canada’s policies towards Indigenous peoples, he is careful to point out that while “many Indian agents during this time enforced repressive policies …. in contrast, McKay offered support to First Nation groups, such as by advocating for them to protect their water rights” (p. 133). Fraser also emphasizes that “in 1887, McKay personally vaccinated 800 people for smallpox, and in 1888 he vaccinated 500 more” (p. 135).

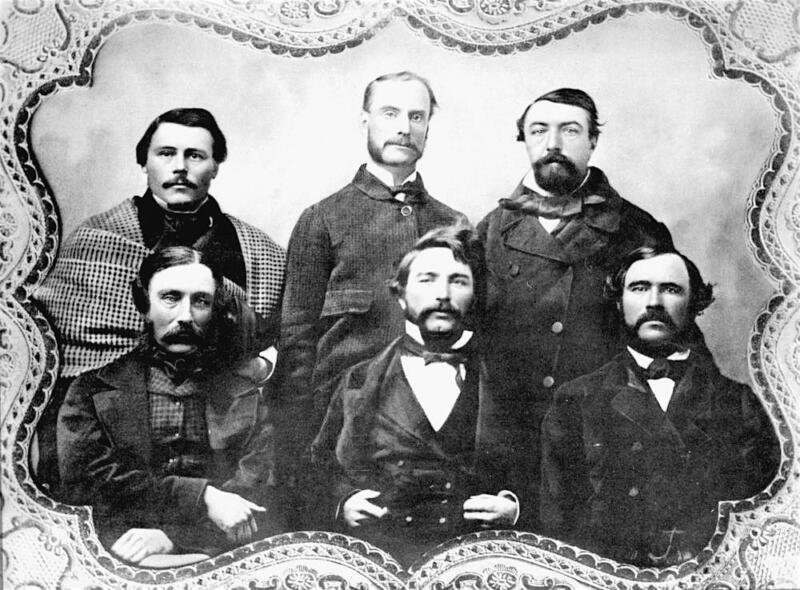

In many respects, McKay’s successful career was a remarkable rags to riches story on the imperial frontier. McKay was born to Métis parents on 31 January 1829 at the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) post of Rupert’s House, now Wakaganish, Quebec, on the southeast shore of James Bay. After attending boarding school in the Red River Colony, McKay joined the HBC as an apprentice clerk in 1844 at the age of fifteen and journeyed west with four other men to Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River. There he worked under HBC Chief Factor Dr John McLoughlin, considered the “Father of Oregon,” and his subordinate James Douglas, the “Father of British Columbia.” In late 1846, following the HBC’s withdrawal from Oregon territory and removal to Fort Victoria, the seventeen-year-old McKay became general manager of the Northwest Coast, based at Fort Simpson at the mouth of the Nass River. Three years later he returned to Fort Victoria where his career began to take off under Douglas. He played a very prominent role in negotiating the Douglas Treaties from 1850 to 1852, with which the HBC and British authorities intended to “extinguish First Nations title to the land so European settlement could proceed peacefully” (p. 36), and was heavily involved in the discovery of coal at Wentuhuysen Inlet, before subsequently founding the town of Nanaimo there in 1852.

In 1856, two years after returning to Victoria from Nanaimo, McKay was elected to the first House of Assembly for Vancouver Island. During his time in the House, the Fraser River Gold Rush began and the colony of British Columbia was created on the mainland. When McKay’s term in the House ended in 1860, he did not seek reelection. Rather, he made his way to Fort Kamloops where he became Chief Trader for the HBC. For the next five years he worked hard to successfully expand the HBC’s retail trade. He then transferred to Fort Yale in 1868 and a few years later in 1872 he became Chief Factor of the HBC. As Fraser writes, “with the position, McKay joined a small number of other Métis men who had advanced to the position of Chief Factor for the HBC in Canada,” a considerable accomplishment, as he now enjoyed “’the status of an officer and a gentleman’” (p. 121). In 1878 McKay left the HBC. It is not clear if he was retired or fired. After a two-year stint as manager of the Inverness Cannery, which brought him into contact with the Tsimshian people, his relationship with whom was apparently fraught at times, McKay worked for the federal government as head of the Census Department for British Columbia. In 1883 he took on his last important position, this time as Indian Agent for the government of Canada for BC.

Indian Agents are controversial figures in modern Canadian history. As Fraser writes:

During much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries [in fact from the 1870s until 1960s – JH], First Nations peoples in Canada were considered wards of the state (meaning they were placed in the care of the government). Under the terms of the Indian Act, their decision-making rights were taken away and vested in the federal government. Indian agents were responsible for making sure that federal policy was followed. As the government’s representatives on reserves, they exercised great power over First Nations peoples, even at times overriding bands’ traditional political authority and making decisions about their religious and cultural practices (p. 129).

It was unusual for a Métis to become Indian Agent, but McKay’s successful career in the HBC and his years of experience working with First Nations communities on Vancouver Island and the BC mainland made him an ideal candidate for the position. He had learned the language of the Saanich people and spoke Chinook Jargon, and as a result McKay’s active engagement with Indigenous communities helped to ensure the steady settlement and economic exploitation of Vancouver Island. During this formative phase in modern BC history, the European population was a tiny minority dependent upon the First Nations for resources and labour. As a consequence, Indigenous people played a vital role in the economic life of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia and were well placed to prosper from the emerging capitalist and colonialist economic system that emerged in the first half of the nineteenth century. After Confederation, however, and as the non-indigenous population grew and the native population declined, indigenous peoples were increasingly isolated from the economy and society.

As Federal Indian Agent, McKay clearly played a prominent role in this process. Yet Fraser appears to be reluctant to engage more fully with issues such as this. While Fraser’s biography provides us with an excellent introduction to a man who played a very important role in the founding of Nanaimo and more significantly in the history and development of modern British Columbia, it needs to be better contextualized as we get little insight into the broader society, mentality, and history in which McKay’s life was lived. The author’s emphasis on McKay’s Métis heritage and the role of Métis in building BC is also certainly warranted, as this is often neglected or minimized.

As a Métis officer in the HBC, McKay was able to operate very successfully in both the world of the Europeans and the world of the Indigenous peoples of BC. However, a fundamental contradiction appears to have governed his life and work. While McKay worked closely with First Nations communities and often fought for their interests, it is clear that he also worked within a brutal system of oppression. It is impossible to understand this system without exploring its pre-history. Here more context and analysis would have been useful. During McKay’s working life, the position of Indigenous peoples changed dramatically. Whereas they were active traders and a crucial and indeed prosperous component of the labour force in the colonial era, by the time of McKay’s death in 1900 they were not just increasingly isolated and excluded from economic and social life, but were subject to the oppressive and destructive Indian Act of 1876 and the horrors of the Residential Schools. But how and why did we get to this point? What was McKay’s role in this transformation? How did he understand what was happening? And what is his ultimate legacy? At a time when the ghosts of Canada’s past, hidden in plain sight despite the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports, are coming back to haunt the nation, we desperately need the answers to these questions if we are to come to terms with our dark past.

*

John Hinde teaches history at Vancouver Island University. He is the author of Jacob Burckhardt and the Crisis of Modernity (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000) and When Coal Was King: Ladysmith and the Coal-Mining Industry on Vancouver Island (UBC Press, 2003). Editor’s note: John Hinde has also reviewed books by Mike Bechthold and Jan Peterson for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster