1218 Chennai, a place in between

MEMOIR: Chennai, a place in between

by Jane Frankish

*

It was the last week of October 2002 and we were homeless, jobless, and rootless. This is just the way it was when we entered Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu in Southern India. Our home for the previous eight years had been Kuching, the capital of Sarawak in East Malaysia. This is where I had given birth to my daughters, Tara and Durga. We were settled there and enjoying life, when Ranjan, my partner, was invited to apply for a position in Vancouver, British Columbia. There was an initial resistance but we slowly grew into the idea that Canada might offer the most supportive environment for our multiracial, multicultural, multinational family.

Long after contracts had been exchanged, just as we were poised to depart, the job unexpectedly collapsed. There seemed to be no value that we could retrieve from the situation. Ranjan’s father had said, “It’s like backing a race horse that has fallen down dead on the track.” Various family members had stood with us for a while poking at the carcass but we could not bring ourselves to bury it. We were still running the race, a strange momentum carried us and we found ourselves tumbling into Tamil Nadu on the way to Canada. Chennai was a diversion, an interlude of sorts, on our journey from Sarawak to British Columbia.

My family and I arrived at Chennai International Airport after a four hour flight from Kuala Lumpur. As we were waiting at the baggage reclaim carousel, an announcement came over the PA system that our bags had been rerouted to a pick-up point some distance away. There was a collective murmur as everyone moved anxiously amidst concerns about lost luggage. At the new pick-up area, the luggage came into the hall on a raised conveyor belt. Some bags were standing up giving them an animated appearance. As our bags came forwards, I thought they looked like long lost relatives. I lost sight of them momentarily as they plopped onto the carousel, glimpsing them through the sea of hands reaching in to retrieve what was theirs. We went in and grabbed what was ours.

It was late when we got out into the heat of the Tamil Nadu night. The air was heavy with diesel fumes and the scent of the monsoon rains. We loaded our bags in the back of a taxi van and told the driver to head for the city. There were many others going our way, it wasn’t a race, it just felt like one.

*

The taxi van turns off the Poonamallee Road and pulls into the driveway of YWCA International Guest House. The entrance, foyer, reception and dining room all have a floor of deep red tiling. The moment I step into the guest house I am reminded of the ‘wine dark sea’ of Homer’s Odyssey. The colour leads us through the entrance and upstairs to our room, which is simple, spotlessly clean and comfortable, with two double beds and a large bathroom covered in tiny green tiles.

I look at our bags and I feel a sense of loss. Most of our stuff has been shipped to Vancouver directly from Kuching and we have packed a motley mix of garments that we had kept at my in-laws’ house in Kuala Lumpur. The children have a selection of leggings and T-shirts, I have some old slacks and tops and Ranjan has brought black cargo trousers and white cotton T-shirts. I find it comforting to have these old clothes, they give me a sense of the familiar in the midst of a new adventure. I think of where we have just come from and it doesn’t seem so far away.

In Kuching, you learn to live with the sun. Dawn always breaks at 7 am and dusk falls at 7 pm. Ranjan and I used to go to the market early in the morning and after shopping we would have breakfast at the Hong Huat Cafe where we would talk over soft boiled eggs, kaya toast and coffee. I recall the old man who sits in a chair at the 4th Mile Market, peeling Sarawak pineapples and carving out the eyes in diagonal groves. I am always grateful to see the pineapple man, preparing pineapples because his fruit is sweet and easy to serve. He sits alone at the edge of the vegetable market, at the place where it becomes the fish market. I used to rely on him being there, and on the odd occasion that he was not, I became worried about him. I wonder now if he misses me. He did not know my story but he knew I loved Sarawak Pineapple. I look at my sleeping daughters and think of the times they had kicked off their slippers and run around the coffee shops in Kuching. I realize that I am going to miss the freedoms of daily life in Kuching. I loved raising my children there.

*

The following day we all crammed into the back of an auto-rickshaw and headed into the city centre, to an area called Egmore, which the YWCA receptionist had called the ‘fancy area.’ We left the sanctuary of the guest house to meet life, greet life, city life, outside life, street life, billboard life, cinema life, river life, sewer life, stinking life, beach life, decaying life, poverty-stricken life, animal life, temple life, colourful life, ourselves in life, the energy of life. We told the auto driver to stop and the four of us stepped out to join the fray.

We wandered along in the hot sun, seeking the covered walkways of the red brick buildings on Mount Road, as we headed for Higginbotham’s bookshop. The moment we entered, we felt the familiar relief of air conditioning. Ranjan and I were on a mission to find out more about Chennai and we looked for books on temples and museums. Tara and Durga ran to the children’s section where they found the familiar Teletubbies and a Malaysian comic book called, The Kampung Boy. We had entered a sanctuary and, immersed in the coolness of the air conditioning, we settled into the books. We made plans, read tales, learnt from the scholars and delved into the spirituality of the place.

*

We step outside our palace of books and continue walking along Mount Road. There are many shops and stalls laden with books. Booksellers pack into tiny slivers and slots between the shops, books are stacked under tarpaulins, all smelling musty, each book holding the other book up, creating a literal store of knowledge. Chennai is a city of closely packed stacks and as you go down one stack and back up another, you can see the poverty line, as though it is drawn across the street. The slums seem uninhabitable, there is no space, no ventilation, no sanitation. The rich seclude themselves in plain sight. The middle class is busy, serving the rich and feeding the poor, seemingly squeezed between wanting more and fearing less. People are further blocked into caste, which layers them into rigid hierarchical groups. India has been stacked for centuries in a social organization that seems to carry the weight of time.

The heavy mid-day congestion slows Chennai’s constant flow. Auto-rickshaws and motorcycles race along, weaving in and out of the crawling traffic, people hang on the side of buses and lorries, jumping on and off whenever they please. As we walk along, there are beggars at our feet, reaching. Poor people squatting with their chins on their knees, blind people and deformed people, impossible versions of people, sights that we cannot ignore. Destitute children in the crowd, grabbing and pulling at you with their hands and their charm. Women in bright saris accentuate the constant movement of the crowd. There are street vendors standing stationary, selling watermelon slices and orange drinks. A myriad of colours but the colour that you really see, the colour of the buildings, the colour of the soil, the colour that you will take home with you, is red. Red is the colour of Chennai.

I think of London and I remember how, in the crowded underground, I used to look for the advertising panels presenting the ‘Poems on the Underground’ public art project. It was here, in the most unlikely of places, grasping onto the handhold and being swung about by the train’s motion that I had first come across classical Tamil Poetry. I remember a poem by the anonymous poet known as Cempulappeyanirar which means “he of red fields and pouring rain.”

What He Said

What could my mother be

to yours? What kin is my father

to yours anyway? And how

did you and I meet ever?

But in love our hearts are as red

earth and pouring rain:

mingled

beyond parting. — Cempulappeyanirar (1st -3rd century AD), translated by A.K. Ramanujan

I am jolted back from my thoughts. I help my children negotiate the Chennai street, as motorcycles and bicycles halt suddenly at the curb-side, allowing passengers to jump off in our path. Auto drivers and street people shout at us to come this way or that and we enjoy the engagement while trying to stay out of their designs, whatever these might be. Ranjan, who was born in Jaffna, just across the waters from the Southern tip of Tamil Nadu, seems to be totally at home. He is finding a fluidity of belonging that I don’t think even he knew he had. He jokes with one fellow in Tamil and rebukes another with street smart ease. The kids and I are thrilled, laughing at Ranjan who seems oddly alien to us and yet so at home in his own otherness.

I feel the exhilaration of the city and its chaotic energy reflecting my own uncertainties. I think of how I wriggled free of Kuching, how my best friend could not bear to see us go, and so didn’t look. I did the same, I said my goodbyes lightly, as if I would be returning. As I walk on, I allow myself to feel the wrench of leaving. I know I have not processed these emotions fully and I am happy to be distracted by the scene in front of me. I wonder how I will make new friends in Vancouver.

*

We walked up Mount Road to the corner of Blackers Road looking for a vegetarian restaurant called Hotel Saravana Bhavan. The Saravana Bhavan chain of restaurants was reputed to strike a perfect balance between affordability, authenticity and quality. It would become a regular pit stop in our wanderings around Chennai. I would look out for the famous red logo, a lotus with closed petals forming the letters HSB. When we ate here, we felt comforted that we were heeding my mother-in-law’s warning.

Our friends and relatives had cautioned us about making the trip with our young children. Ammamma, as we all called Ranjan’s mother, had said, “Do not drink the tap water and do not eat the meat.” Uncle Mahathevan who maintained a property outside of Chennai, had suggested that we stay at his place to avoid the crush and clamour of the city. Srini, a friend in Chennai, had even said, “don’t come at this time, there will be floods.” It had been a particularly rainy monsoon season, and there was a possibility of cyclones and flash floods. We had thought they were all being overly concerned. After all, we were familiar with the pollution and the congestion of Kuala Lumpur and we had experienced floods in Sarawak. “We’ll take care with the food and the water, and we will be alright with the rest,” Ranjan had said to me rather confidently.

*

The steam from the cooking, the ring of utensils working on cast iron frying platters, the clatter of metal serving plates and the constant in and out movement of chairs as people came and went, all give the restaurant the feeling of a moving train. All the waiters are dressed smartly, in starched white cotton shirts with neatly placed white caps on their heads. They know exactly what is what and who is next. Many uniformed but barefooted boys are clearing and cleaning the tables enabling an efficient circulation of people. The restaurant is in movement as we step in and take a table. We order quickly, the waiters move on, this is the pace. The kids choose Idli and Appam, Ranjan and I each have a full Thali. We were used to eating this food but this mix of perfection, speed and spice is a completely new experience.

Even in Malaysia, after Indian food, our treat was always a Bru filter coffee and hot milk for the kids. We would pour the strong sweet milky coffee from its metal tumbler into a small metal dish and back again to cool the drink down. My four-year-old daughter, Durga, spills her milk on the first pour. The steaming white liquid spreads over the marbled plastic tabletop, and we have no way to dam the flow. One of the boy servers swoops in and swipes up the spillage with his cloth and our waiter gets her a new tumbler of milk. It all happens in an instant, we have no chance to call for attention, to ask for a replacement or even to thank the servers.

Durga tugs at my shirt and leans into me. She isn’t feeling well and it is beginning to rain outside. As we leave the restaurant with full tummies, we drop coins into a beggar’s tin cup, the chink of the coins sounds our privilege. Our children’s questions are unbearable. I explain, our coins are a gesture and this is what we will give today. I have a sudden unease about the order of the world, and about what might happen next. I have become detached from the daily certainties of our life in Kuching. In Chennai, the past and the future fall away, as we touch the eternal present. Back at the guest house, I step gingerly onto the wine dark floor and it feels like I am being drawn into the red earth of Tamil Nadu.

*

At breakfast, the following morning, Tara played with the children from the neighbouring tables. They were all in high spirits and their laughter reverberated off the tile floor, echoing into the vacuous spaces of the YWCA. They ran around the reception area of the guest house, encouraged in their rambunctiousness by the staff who appeared to take delight in their behaviour. Durga had joined in the fun but her cold was developing at an alarming rate. She was feeling out of sorts and we decided to stay in for the morning. Her temperature shot up and her breathing became laboured. The room, with its subdued green walls and scant curtains had seemed pleasant before but with our little girl in bed, the ambiance turned sickly. We sat with her, encouraging her to drink water but her condition appeared to be getting worse. Her chest was heaving violently and within the hour we had called for a Doctor.

The Doctor arrived carrying a medical bag of the type I had known as a child, in the days when doctors still made house calls. I remember, I would peer anxiously into the black bag full of compartments. I was peering anxiously again. The doctor drew up an injection and administered it into Durga’s arm. Within a few minutes, her breathing was more relaxed and not so laboured. The Doctor seemed to have performed a miracle. We had all been silent while the Doctor waited for the medication to take effect but as he was tidying his bag to leave, we began to ask questions. He explained that it was probably a bacterial infection and that he had prescribed antibiotics, and yes, he said, an infection can hit the airways that quickly. He had seen it before in Chennai, in the rainy season. He told us that it can be fatal if not attended to promptly. I was rooted to the spot, we had narrowly missed a catastrophe, and we had been forewarned.

The Doctor turned to leave and, as he put his hand on the door, he stopped, “There’s something I should tell you.”

I gulped, thinking that our relief had been premature. “Yes,” Ranjan responded bravely.

“There’s a young girl staying here. I attended to her yesterday and I diagnosed her as having Typhoid Fever. You should not let the children play together and I feel you should leave this place as soon as you can.”

The Doctor was apologetic and seemed uncomfortable about having betrayed his patient’s confidence. He left, quietly closing the door behind him. At that moment I felt the weight of all the warnings sink in. I wanted to leave immediately and we decided to take up Uncle Mahathevan’s offer after all. Srini had already arranged to pick us up the next afternoon to take us to the Hridayaleeswarar Temple. We would now leave for Uncle’s house straight after the trip.

With Durga recovering as quickly as she had gone down, we made a rash decision. The next morning instead of resting, we went out touring. The impulse, I think, was to leave the sick room, to simply put it behind us. We walked through the garden of the guest house to the Poonamallee High Road. On either side of the path was a row of potted plants, bougainvillea, jasmine and green ferns, all beaded with water. I had heard the rain the night before but had not paid attention to the extent of the downpour. The palm trees in the garden looked subdued but the sturdier shade giving trees seemed vibrant. I inhaled the refreshing after-rain smell of water soaking dry earth and noticed a recurring redness. Mineralogists call the scent produced when rain falls on dry earth ‘petrichor,’ a term whose root goes back to ‘rock’ and ‘the blood of the gods.’ I thought again of Cempulappeyanirar‘s gentler image of the same.

*

At the gate, a yellow auto makes a beeline for the YWCA entrance, the exhaust sputtering as it pulls up to us. We want to go to the Government Museum to see the Bronze Gallery and the famous Nataraja of Thiruvalangadu. As we set off, Ranjan impulsively tells the driver to take a detour via Chennai’s exclusive Poes Garden, to see the movie Superstar Rajinikanth’s house. Back in Kuching, Ranjan had brought home some Rajinikanth movies and our kids had got a taste of ‘Kollywood.’ Muthu and Baasha had become our favourites and we were all truly enamoured of this movie superstar who rides a horse-drawn buggy and an auto-rickshaw with equal panache! Durga is getting chirpy now and we are in good spirits, as we set off to see our hero’s house. We take a right turn into Rukmani Lakshmipathi Road and come upon a flood. The rains had overflowed the Cooum River and its waters had submerged the road. The driver steps out of the auto and makes a quick assessment, he then jumps back in and drives straight into the water. Shouting over the revving engine, he promises cheerfully that he will get us to the other side. The other side, to be fair, does not look that far away but the engine fails right in the middle of the crossing with a sad final putt.

We sit there with the murky water gently lapping at the sides of the cab, teasing our dry feet. The driver gets out to push and, of course, the harder he pushes the more water enters the cab. Next he tries some kind of manual start but the engine is too wet. We have come to a full stop. I think we can get out and walk but I do not know what we will be stepping into, and the fear of disease is fresh in my mind. As we wait, the water settles around us and after more pulls of the starter lever, the auto suddenly spurts back to life. The driver slaps his foot down on the accelerator and we drive out of the flood with gusto! When we arrive at Rajinikanth’s house, it looks just like any other posh house in Poes Garden. I feel a little let down but on the other hand, we have come through a Chennai flood and we have found our very own auto driving Superstar.

*

That afternoon Srini came to take us to the Hridayaleeswarar temple in Thirunindravur. Ranjan and I knew Srini from a chance encounter at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the early 1990s. Our paths crossed several times in the near deserted galleries and as we kept bumping into each other, it seemed natural that we should talk. We started a conversation that continued over hot chocolate in the Museum cafe. Ranjan and Srini would later collaborate in creating an online temple based on the founding myth of the very temple we were about to visit.

There was a keen sense of anticipation as we drove along the wide open road that seemed to merge into the surrounding fields. Cows marked the roadside sitting placidly in groups, gently chewing the cud. I remember there was some urgency to get to the temple before dark. Our minivan hurtled along, bouncing through water filled potholes. We turned off the main road and drove through a series of villages. I saw people getting on with their evening and, as we passed by, they glanced at us casually, as though we were a familiar part of their scene. When we stopped at our destination people gathered around to see who or what had arrived.

The moment we got down, Srini and Ranjan chatted with the elders and Thirunindravur opened up to us generously. Everyone was gesturing and getting excited but smiles were turning to frowns as the temple was apparently closed for renovation. There was more animated conversation. As I waited, I scrunched my shoes in the earth, Srini and Ranjan came back to the van, grinning. They had gained access, so we all got back in the van and took the short drive to the Temple. Once we were inside the compound a priest came forwards holding a large iron key which turned easily in the lock of the temple door.

Inside, it was dark and water was dripping from the ceiling, the floor was slippery and there was a clawing aroma of lamp oil and camphor. We went in further and, as my eyes adjusted, the cavernous temple architecture slowly revealed its form. The priest lit one of the lamps and showed us around, the walls glistened greasily in the wavering light. We stopped at every niche and put our hands together in praise of its deity. In the inner sanctum, standing next to the Lingam icon of Lord Shiva, we see a sculpture of the sage Poosalar. Legend has it that, as the great King Kadavaraja was preparing for the consecration of his grand Kailasanathar temple in Kanchipuram, Lord Shiva had appeared to him saying that he would not be there because he would be attending the consecration of another temple. Incensed at being upstaged, the King had looked for the offending temple throughout the land but there was no such structure. He found only the poor sage Poosalar, who had realized the temple ‘brick by brick’ in meditation. The humbled Kadavaraja had then built the Hridayaleeswarar temple, the Temple of the Heart, at this very place.

*

Perhaps it is the heat and the smell of old camphor, incense and oil but I remember feeling overwhelmed and having to go outside. Out in the fresh air, we thank the priest and are about to leave, when one of our party invites us to go up onto the temple roof. We are led to a tall bamboo ladder leaning against the wall. Ranjan carries Durga, while Tara pulls herself up excitedly onto the first rung of the ladder. I go up carefully, as I have to keep Tara covered while balancing myself. To the delight of everyone watching from above and from below, we make the climb safely. We come off the top of the ladder and walk towards the western edge to face the setting sun. Apart from the central tower which is scaffolded and clearly in need of repair, the temple roof is flat. Our group is growing in number and there are probably eight or nine others with us now, among them, children who have clambered up to join ours.

The view is expansive and, in the evening light, I experience the flatness of the land. The monsoons have turned the scene a lush green, which is complemented by the dark red of the soil. The Thirunindravur Lake is full and buffalos laze in the shallows, a blue heron takes to the air and I spot other birds feeding by the lake. Thickets mark the landscape, here and there, small groups of palms stand out looking lonesome. From our vantage point, I can see entire villages, with temples nestled in their midst. Ranjan and Srini talk about how each node on the Internet is located at its centre, and how, in the same way, the deity of a temple, is always at the centre of the cosmos. In approaching the deity in the inner sanctum of a temple, you go towards that cosmic centre. What Poosalar shows us is that you don’t need the physical temple, you can get to that same centre by going inwards, in prayer and meditation … into the ‘heart.’

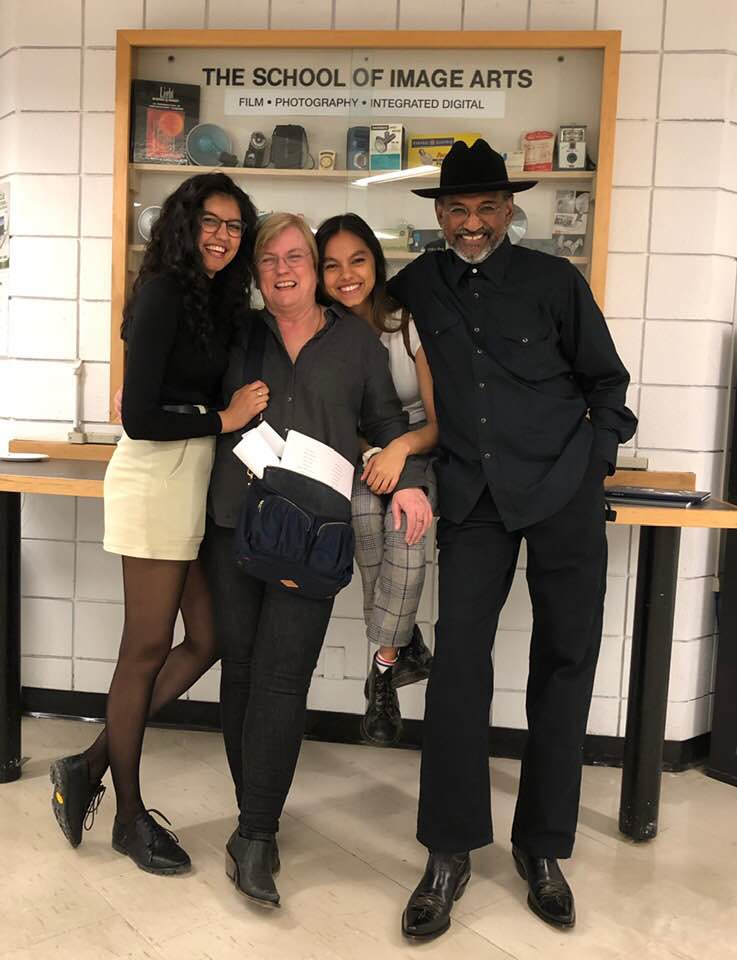

I listen and I am suspended between all that has happened and all that is to come. When our Canadian landing papers had arrived, I was surprised to find the children’s’ mother tongue officially recorded as Tamil, a language they did not speak. I had listed their mother tongue as English, and as their English mother, I had wondered why the authorities had changed my entries. As I stand on the roof of Poosalar’s temple, I worry about what lies ahead for the girls in Canada, but the warm Thirunindravur breeze lets me know they will be alright there, just as they are here, with me, on the temple roof. I look at them and see that I am the centre for my children.

*

It was late when Srini dropped us back at the YWCA, we quickly gathered our things and headed for Injambakkam in a taxi. Uncle Mahathevan’s house was down a narrow lane away from the main East Coast Road, close to the famous VGP Amusement Park. Uncle was in Malaysia at the time, and his caretakers welcomed us into the house, with sleeping children in our arms.

The next day, Tara and Durga played in the garden with the caretakers’ kids, digging up earth, running away from little snakes, hiding in sheds and generally screaming out loud in delight. When they had exhausted themselves they all settled down to work on a jigsaw puzzle. Ranjan and I sat on the swing in the flower garden smoking cigarettes and drinking Kingfisher beer. We watched the plumes of cigarette smoke rise in waves and disappear from view, we laughed and made analogies between our journey and the VGP roller coaster which we could see clearly from Uncle’s garden.

As the evening drew to a close we finalized the plan for our tour of Tamil Nadu. We were off again. It felt like the momentum was building up that would carry us all the way through to Canada. We would first go to Mahabalipuram, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Starting there, we would take a circuitous route, which would include Kumbakonam, Swamimalai, Thanjavur, Tiruchirappalli, Chidambaram and Puducherry. The highlight of the trip would be a visit to Chidambaram and the Thillai Nataraja temple where, according to the faithful, Lord Shiva performs his eternal dance. After about a week or so of touring, we would end up at Srini’s house in Chennai to meet his family and celebrate Tara’s sixth birthday.

In the morning the car that Uncle’s caretakers had organised for us arrived. The kids got in with me at the back, Ranjan got in the front, and we set off on the drive in great anticipation. As the journey progressed, the engine began to sound wrong and the steering seemed off. We meandered along the road at a very slow pace and, as we all swayed back and forth, the driver insisted that everything was fine. When we got to Mahabalipuram, Ranjan and I looked at each other knowing that we would have yet another problem to deal with, first though we would take in the sights.

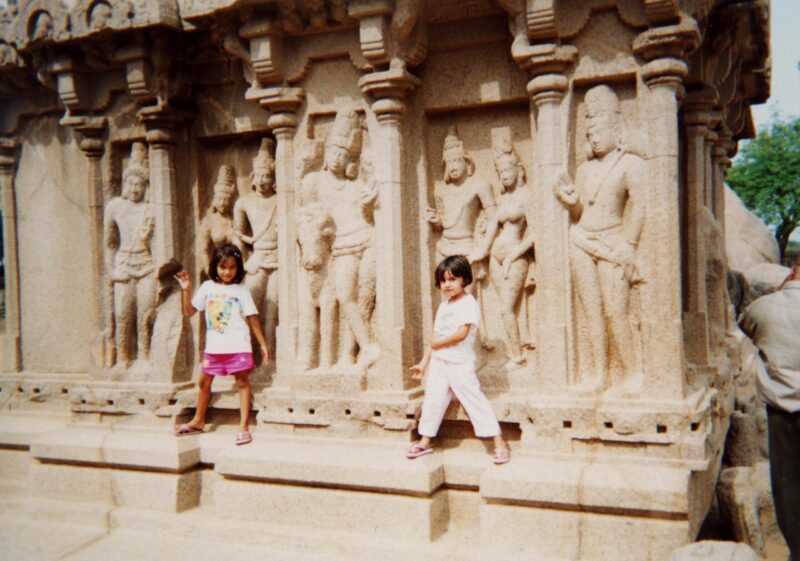

Leaving our bags in the car, we started at the Five Rathas temple complex and then walked to the Mahishasuramardini cave temple. Next, we headed for the monumental stone relief known as Arjuna’s Penance or the Descent of the Ganges. Ranjan and I discussed our next move while taking in this complex carving. Tara and Durga enjoyed naming the animals and we all looked for the fabled ascetic cat who feigns piety to trap and eat gullible mice. We let the girls go on ahead of us but they came running back to tell us about a snake that people were having to jump over on the way. Ranjan and I took charge of them but we did not come across any snakes. We ended up joining in the fun of sliding down the smooth hillock on which the giant rock, known as Krishna’s Butterball, is perched.

Returning to the car we carried out our plan. Ranjan gave the driver some money and told him that we would not be continuing with him, and leaving me with the girls and the bags, he crossed the road to engage with a group of men standing around their Ambassador cars. We had seen the men standing there when we arrived and guessed that they must be drivers. What a negotiation, on this dusty street in Mahabalipuram, Ranjan was finding a natural connection to his mother tongue. We walked over to meet our new driver with his fully serviced Ambassador. As we left Mahabalipuram behind, I sat between my children and put my arms around them. I saw that they were themselves mingled like red earth and pouring rain.

*

There is a small strip of greenery running along the sidewalk on the west side of Quebec Manor, at the intersection of Quebec Street and East 7th Avenue, in Vancouver. It is September 2020 and haze from the forest fires raging in California has filtered the sunlight, causing a sharpening of colour. I am attracted to the yellow of the long stemmed daisies just behind the holly tree at the top of the strip. They are in perfect bloom. I pick a few heads as well as some large white chrysanthemums that are blooming close by.

I go up to our first floor apartment and place the flowers before the Nataraja icon that had once belonged to Ammamma. Both my in-laws have now passed away, and Ranjan has brought this icon home from Kuala Lumpur, complete with Ammamma’s string of prayer beads and holy ash still marking the blackened bronze. When I first went to my in-laws’ house, I would place jasmine flowers at the icon’s feet. Later my girls would run behind their beloved Ammamma chatting and collecting flowers from the garden with which to adorn this Nataraja. Today, I bring flowers to Shiva Nataraja who stands in our bay window, left foot raised, bestowing grace.

I reflect on the day we landed in Vancouver, with bags that were bigger than Tara and Durga. We were all so tired and disheveled. I had felt vaguely criminal when Immigration Canada snapped our photos. We had waited in the fog for a cab to take us to our landing address, the downtown YWCA. I am comforted in remembering the Thillai Nataraja temple, where I had bought colourful flower heads at the entrance to offer to Shiva Nataraja who presides there, and here, in the temple of the heart.

*

Jane Frankish is a Master’s student in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University. She is a librarian who enjoys creative writing and poetry. Jane blogs here. Editor’s note: Jane Frankish has also contributed “Letters from the Pandemic 16: Dear Percy” to the Pandemic Letters, a collaboration between Graduate Liberal Studies at SFU and The Ormsby Review.

*

Endnotes & Images:

Baasha. 1995. Photo Gallery – IMDb photos, including production stills, premiere photos and other event photos, publicity photos, behind-the-scenes, and more. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0139876/mediaindex 29/07/2021

Thiruvalangadu Nataraja. Centre for Art and Archaeology. Virtual Museum of Images and Sound. https://vmis.in/ArchiveCategories/collection_gallery_zoom?id=1027&search=1&index=54058&searchstring=thiruvalangadu 29/07/2021

Benson, Gerard, Judith Chernaik, and Cicely Herbert. 2009. Best Poems on the Underground. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, p. 49

Saravana Bhavan, Mylapore. Dr .Manickavasagam 2008. 26/08/2021

http://wikimapia.org/376163/Saravana-Bhavan-Mylapore

Higginbothams. Pen, Paper and Blue Ink. No Date. 26/08/2021 https://sahanibhumika.wordpress.com/2014/05/14/higginbothams/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1218 Chennai, a place in between”

So lovely to read this, Jane. Thank you.

Jennifer thank you for your kind comment, I am glad you found this – jane