1216 Despatches from the Pit

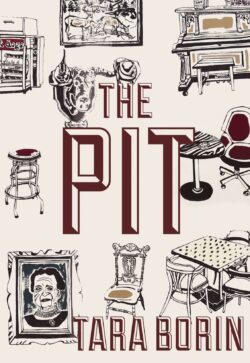

The Pit

by Tara Borin

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2021

$18.95 / 9780889713949

Reviewed by Michael Turner

*

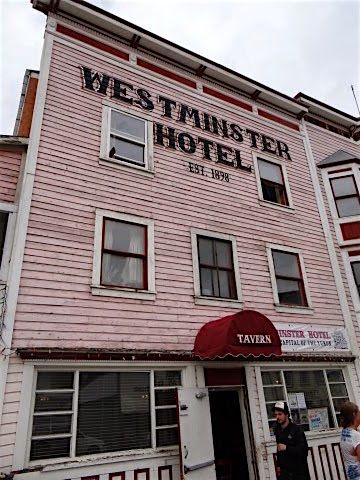

Tara Borin’s first poetry collection The Pit takes its name from a Dawson City hotel, “the Yukon’s oldest and longest-running.” Christened the Westminster Hotel in 1898, its building (rooms, bars and a diner) has undergone numerous additions and renovations, which it wears today like a cartoon hobo’s coat. Yet unlike the hobo, the Pit (as it is known to locals) has stayed where it started: a fixture on the town’s main drag, a cultural hub and de facto museum dedicated to humanity’s highs and lows. I too had my “first and last beer” at The Snake Pit (as I knew it in 1992) when in town to perform with Hard Rock Miners at the Dawson City Music Festival, and I drew on the Pit’s eccentricities (and clichés) when I accepted an offer from the North Burnaby Inn to “do something” with its lounge in 1993, what I ended up calling the Malcolm Lowry Room.

Tara Borin’s first poetry collection The Pit takes its name from a Dawson City hotel, “the Yukon’s oldest and longest-running.” Christened the Westminster Hotel in 1898, its building (rooms, bars and a diner) has undergone numerous additions and renovations, which it wears today like a cartoon hobo’s coat. Yet unlike the hobo, the Pit (as it is known to locals) has stayed where it started: a fixture on the town’s main drag, a cultural hub and de facto museum dedicated to humanity’s highs and lows. I too had my “first and last beer” at The Snake Pit (as I knew it in 1992) when in town to perform with Hard Rock Miners at the Dawson City Music Festival, and I drew on the Pit’s eccentricities (and clichés) when I accepted an offer from the North Burnaby Inn to “do something” with its lounge in 1993, what I ended up calling the Malcolm Lowry Room.

Even before cracking The Pit the reader can’t help but notice on its back jacket how often the term “dive bar” is used to prime us for what lies inside. For literary readers new to English slang, a “dive” is an unkempt place, usually of ill-repute; when applied to a bar: a popular staging ground for postwar anti-heroic activity, mostly by and about forthright urban white guys like Jack London, Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski and, more locally, Peter Trower. But does the term travel well to rural communities? Well enough that it can reduce the improvisatory nature of these communities to a cartoon strip of cultural stereotypes, a tendency that equates transgression with failure, abjection with pathos. A “dive bar” is largely an urban phenomenon, authored by urban eyes. Its antonyms — fern bar, wine bar, cocktail lounge — belong to a social class who care only about the absence of what threatens them.

Organized in five sections, The Pit is a perfectly spare 72-page book that rewards the reader as much with what isn’t there as what is. Part of this reward manifests in a desire to return to its poems and bask in their careful language, or in ambiguities and complications like those we find ourselves mired in, no matter where we are; but also to appreciate how the author did it, their exquisite combination of narrative propulsion and lyric meditation. As for absences, most notable is the omission of Time’s context-setting world events. The only instance of anything external entering The Pit is through mediated sources: a televised Canucks game (muted by the bartender), another Canucks game (or is it the same game?) on a resident’s clock radio and an unnamed Rolling Stones song (“Satisfaction”?) performed by a touring cover band. Everything taking place in The Pit could have happened at any point since 1970, the year the Canucks entered the NHL. (Everything except the author, that is, who wasn’t born yet.)

The Pit’s opening section, “Beer Parlor,” is rich in Judeo-Christian symbolism. Though its first poem “Desire Paths” beckons Pit patrons with a more primal “husky’s howls,” its opening lines “In the long absence/ of light” echoes the Genesis creation myth, a clever reversal where a pushy GOD is the “husky’s” pulling DOG. Indeed, it is these (Ginsbergian?) “howls” that “drive us/ from our singular// cells to trace paths/ pressed in snow,” a pilgrimage where the patrons, once arrived, genuflect (“flirt,” “dance”) in regalia (“toques,” “parkas,” “boots”) before contributing “our secrets” to the bar’s collection plate “in exchange for an ounce/ of forgetting,” which is of course the sermon — like the “jukebox/ onstage” is the church organ and the “whirling stars/ on our tongues” the flesh of Christ, as given in a Christian Communion service. The conceit established, the poems that follow in this section can be read accordingly: “Church Key” is the cross the bartender uses as a bottle opener, the “List of Duties in a Subarctic Dive Bar” their Commandments, etc.

As implied by the titles of the following two sections, “Rooms for Rent” and “The Regulars”, the focus is on portraiture. But portraits abound throughout The Pit, and they are expertly rendered; irreducible to a stanza or two, they need to be read in their entirety, just as their subjects’ need to be heard with more than a bartender’s absent uh-huh ears. Consider this from “List of Duties in a Subarctic Dive Bar”: “If someone reveals residential school horrors,/ listen with your whole body.” Later, in the “Hard Stuff” section’s “Telephone”, the attentive body has no choice but to retract. Here is the left-margin that precedes the poem’s right-margin follow-up:

I am the one

serving him beer

after beer, trying not to think

about who is left at home.

It’s none of my business, I’m not

here to judge.

I take the rent money, the diaper fund

and break the change down for tips.

When the phone rings, the voice

in my ear is stretched thin

by sleepless nights

and distance.

The subsequent right-margin “I” is no longer the “I” of the bartender but the person with whom the drinker shares a baby, the one who “wails in the car seat” while the co-parent speaks into a truck stop pay phone (“is he there”). An interesting decision. Rather than “judge” the situation, Borin broadens it, fleshing out a cycle common to addiction and reproduction, elevating the portrait petit genre to the level of a history painting. Brilliant.

But what of this bartender who is mostly so clearly Borin, our poet? Which of these poems are their self-portraits, if that should matter? Is Borin, like Tennyson, “a part of all that I have met”? Do they, like Whitman, “contain multitudes”? I would think so. Because we are active readers — drawing as much on our own desires and experiences as those shown to us — it is our tendency to imagine what we are reading, and thus we find ourselves projecting. Is Borin the “I” in the erotic “Cribbage & Chill”, happily pegging their way to defeat? The “you” in “Home”? I am satisfied that this is not something that needs to be laboured over. Unlike the bars of Bukowski and Trower, Borin has made The Pit a proprioceptive space, where identities and subjectivities are fluid, plural, intersectional. They could easily be the drunk they are serving — a situation I found myself in when I had my bar, and it had me.

For an Ormsby Review interview with Tara Borin, see here. — Ed.

*

*

Michael Turner is a writer of variegated ancestry (Scottish/ German/ Irish, mat.; English/ Japanese/ Russian, pat.) born, raised and living on unceded Coast Salish territory. He works in narrative and lyric forms, both singularly, as a writer of fiction (American Whiskey Bar, The Pornographer’s Poem, 8×10), poetry (Hard Core Logo, Kingsway, 9×11), criticism and music, and collaboratively, with artists such as Stan Douglas (screenplays), Geoffrey Farmer (public art installations) and Fishbone, Dream Warriors, Kinnie Starr and Andrea Young (songs). His work has been described as intertextual, with an emphasis on “a detailed and purposeful examination of ordinary things” (Wikipedia). He holds a BA (Anthropology) from UVic and an MFA (Interdisciplinary Studies) from UBC Okanagan. Currently he is an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies and Graduate Studies, Ontario College of Art & Design University and a workshop leader at Mobil Art School, Vancouver. Editor’s note: Michael Turner has also reviewed books by Taryn Hubbard, Jen Sookfong Lee, Isabella Wang, and Sachiko Murakami for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1216 Despatches from the Pit”