1212 Considering George Manuel

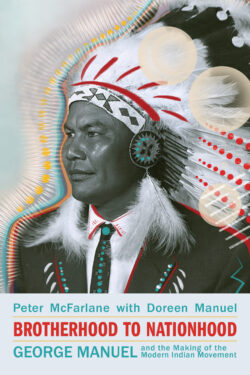

Brotherhood to Nationhood: George Manuel and the Making of the Modern Indian Movement

by Peter McFarlane with Doreen Manuel, with a foreword by Pamela Palmater

Toronto: Between the Lines Books, 2020 (second edition; first published 1993)

$32.95 / 9781771135108

Reviewed by Sarah Nickel

*

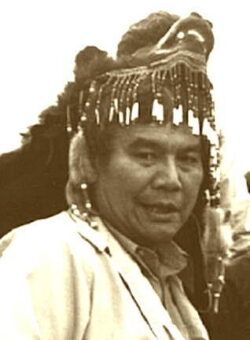

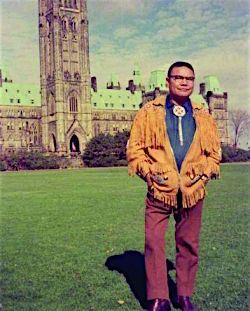

Indigenous women “were every part of organizing [because] the women are the ones who know everything that needs to be done.”[1] These were the words that Doreen Manuel shared with me when we spoke about Indigenous women’s activism and, specifically, the additions she insisted upon in the new edition of Brotherhood to Nationhood: George Manuel and the Making of the Modern Indian Movement. Originally published in 1993, this work is one of those rare examples of scholarship that largely stands the test of time. A detailed and meticulously researched biography of the late, great, Secwépemc leader George Manuel, undertaken with the approval and cooperation of the Manuel family, Brotherhood to Nationhood was, in many ways, ahead of its time in terms of community-engaged research practices and Indigenous-centered histories. Historians and others interested in the modern Indigenous rights movement still widely use this work, and for good reason. But, as McFarlane relates in his updated introduction, as with any work, the original version had blind spots, particularly in terms of women’s political contributions. And this was something he set out to correct with the help of George Manuel’s daughter Doreen.

Indigenous women “were every part of organizing [because] the women are the ones who know everything that needs to be done.”[1] These were the words that Doreen Manuel shared with me when we spoke about Indigenous women’s activism and, specifically, the additions she insisted upon in the new edition of Brotherhood to Nationhood: George Manuel and the Making of the Modern Indian Movement. Originally published in 1993, this work is one of those rare examples of scholarship that largely stands the test of time. A detailed and meticulously researched biography of the late, great, Secwépemc leader George Manuel, undertaken with the approval and cooperation of the Manuel family, Brotherhood to Nationhood was, in many ways, ahead of its time in terms of community-engaged research practices and Indigenous-centered histories. Historians and others interested in the modern Indigenous rights movement still widely use this work, and for good reason. But, as McFarlane relates in his updated introduction, as with any work, the original version had blind spots, particularly in terms of women’s political contributions. And this was something he set out to correct with the help of George Manuel’s daughter Doreen.

By McFarlane’s own admission, he originally did not spend “enough time with the women of the family in researching the book” (p. xviii), and the result was an androcentric view of twentieth-century Indigenous politics that failed to account for Indigenous women’s rich contributions. This was not just a problem with Brotherhood to Nationhood. Indeed, in most of the literature on Indigenous activism and politics, Indigenous women’s activities are marginal at best – a trend in desperate need of correction if we are to truly understand Indigenous political struggles. Thus, Doreen Manuel’s role in this new edition is key. In her preface she outlines several corrections, clarifications, and additions to the story from George Manuel’s journal and family collective memory. This highlighted Indigenous women like her mother Marceline Manuel and Marie Smallface Marule, who were individuals with their own political agendas and activities, not simply supporting actors in the George Manuel biopic as the original edition implies. Marceline, for instance, sold handicrafts and organized fundraisers to help support George’s travel and political activities, but she was also on the front lines of direct action, occupying Indian Affairs’ offices through the mid-1970s to the early 1980s and taking part in the Indian Child Welfare Caravan in 1980. The inclusion of Marceline and others here both elevates and complicates Manuel’s legacy, enabling readers to see the importance of great figures while acknowledging that Manuel could not have done his work without extensive direct and indirect support.

Through twenty comprehensive chapters over four roughly chronological sections detailing Manuel’s early upbringing and community work, and the building of national and international political movements, Manuel’s life and work become a microcosm of the Indian rights movement. This movement was neither linear nor unidirectional in progression, but messy and full of setbacks and disappointments as well as great triumphs. Early chapters scaffold Manuel’s upbringing in Neskonlith, surrounded by family and Secwépemc culture before his forcible removal at age nine to the Kamloops residential school to outline his growing politicization and disdain for state policies.

We are witness to transformative moments – some subtle, like Manuel quietly refusing to pay a doctor’s bill for his son Arthur. Upon learning that the Department of Indian Affairs would no longer take responsibility for health care costs of employed First Nations peoples in 1955, Manuel took, what McFarlane describes as his “first political stand” by refusing to pay (p. 30). This set Manuel on a path of refusing to accept government paternalism and state-sanctioned oppression. Other moments were more explosive and overt – such as Manuel’s 1960 speech to the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Indian Affairs, and his inadvertent, but nonetheless pivotal role in the 1975 decision by the provincial Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) to reject all forms of government funding as an act of Indigenous sovereignty (pp. 194-95).

It was in this final example that Doreen Manuel’s influence on the revised edition is most prominent. She issues a lengthy corrective about decision to refuse funding, which McFarlane interpreted as premature, inappropriate, and ultimately devastating to the UBCIC and Indigenous communities who suffered greatly without government support. Instead, drawing on family knowledge and her own memories, she insists that the funding decision was a positive turning point for Neskonlith, which turned inwards to help community members thrive with collaborative hunting parties, farming, and gardening, and sharing resources (p. 195). Eschewing simplistic and universal narratives about this historical moment, Doreen Manuel uses her local insight to understanding pan-tribal political events as multivocal.

As in the original, McFarlane and Doreen Manuel do not shy away from exposing the personal impact of George Manuel’s political activism. Brotherhood to Nationhood paints a picture of a man relentlessly dedicated to the Indigenous rights movement, whatever the cost. And it did cost him dearly. But the authors carefully balance discussions about the importance of his contributions to national unity through the North American Indian Brotherhood (NAIB) and National Indian Brotherhood (NIB) and to internationalization with political travel and the creation of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) in 1974, with the breakdown of his marriage and alienation from his children. It is here where Doreen Manuel’s input is equally moving and distressing, reminding us that George Manuel was a powerful activist, but like everyone else, he was also flawed. We need to consider both in tandem.

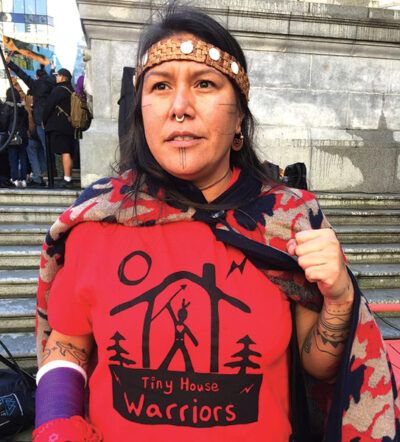

At its root, this is a book about the past, but new materials including a foreword by Pamela Palmater, prefaces by McFarlene and Doreen Manuel, and afterword by Kanahus Manuel draw attention to its continued relevance. In revisiting the words and deeds of activists, “A new edition of Brotherhood to Nationhood,” in McFarlane’s estimation “would bring all these voices back to speak to another generation” (xvi). Doreen Manuel agreed, while also insisting that “even in a book that is primarily about politics and the activism of our peoples, family details are important in understanding the incredible pressures involved in mounting a modern-day movement” (xx). It is thus fitting that Kanahus Manuel – the daughter of noted activist Arthur Manuel and granddaughter of George Manuel – should have the last word. She reflects both on the important work her grandfather and others did, but also demonstrates how this activism continues in largely women-led initiatives like the Tiny House Warriors, a land defender movement opposing the proposed Trans Mountain pipeline. While Doreen Manuel’s voice and interventions thread throughout – bringing community and women’s perspectives through where they were otherwise muted or omitted, Kanahus Manuel’s words look to the future and the challenges that remain.

Ultimately, the changes in Brotherhood to Nationhood are subtle and transformative in equal measure. The new edition does not read like a rewrite – it is still familiar and maintains the important critical interventions it always had – but it’s richer and more complex. Importantly, the additional insights and material provided by Doreen Manuel do not feel unnatural or shoe-horned in as rejoinder to criticism, but rather appear as though they were there all along. As such, this new edition honours and acknowledges the invisible, under-appreciated, and under historicized work of Indigenous women – and offers this classic book new life.

*

Sarah A. Nickel is Tk’emlupsemc (Kamloops Secwépemc), French Canadian, and Ukrainian. She is an associate professor in the Department of History, Classics, and Religious Studies at the University of Alberta. Her areas of interest include comparative Indigenous histories, 20th century Indigenous politics, gender, Indigenous feminisms, and community-engaged research. Her work has appeared in several journals including the Canadian Historical Review, American Indian Quarterly, and BC Studies. Her first book Assembling Unity: Indigenous Politics, Gender, and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (2019) won the 2020 Canadian Historical Association’s Indigenous History book prize. Sarah also recently co-edited a volume on Indigenous feminisms titled: In Good Relation: Gender, History, and Kinship in Indigenous Feminisms, which was released by the University of Manitoba Press in May 2020. Editor’s note: Sarah Nickel has also reviewed Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws: Yerí7 Stsq̓ey̓s-kucw, by Marianne Ignace and Ronald Ignace, for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Doreen Manuel, interview with Sarah Nickel, July 15, 2021

2 comments on “1212 Considering George Manuel”

In an article stressing how women were overlooked in the first edition of a book it’s curious that in two of the photographs of women accompanying the article the first words that appear in the title are “George Manuel’s….”