1206 Interview with Dustin Cole

INTERVIEW: Dustin Cole with The British Columbia Review.

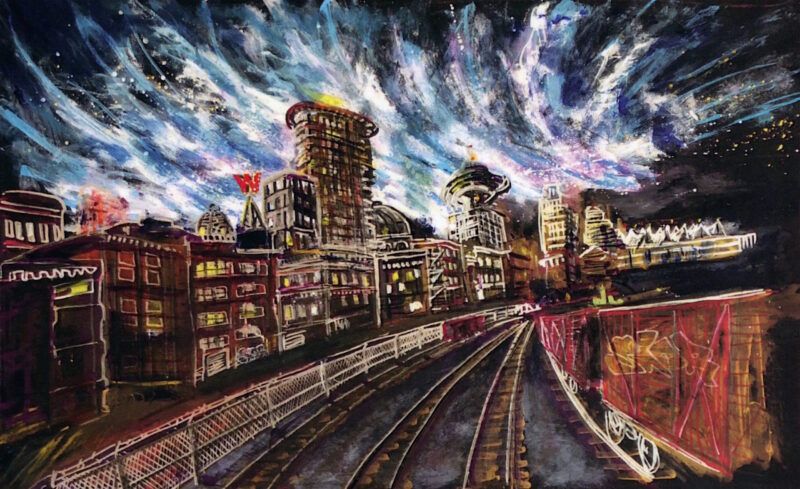

We caught up with Dustin Cole at his brother’s house in Slave Lake, Alberta, to learn the circumstances and inspiration for Notice (Nightwood Editions, 2020), the story of Dylan Levett, a dishwasher from Alberta caught in the gears of renoviction from his apartment on Main Street. “It’s summer 2017 in Vancouver, BC, where economic imperatives are making space less and less accessible to low-income residents,” reads Nightwood’s website blurb. “The rental crisis is intensifying, ravenous real-estate development is thriving and there is a province-wide forest fire emergency blanketing the city in smoke.”

We caught up with Dustin Cole at his brother’s house in Slave Lake, Alberta, to learn the circumstances and inspiration for Notice (Nightwood Editions, 2020), the story of Dylan Levett, a dishwasher from Alberta caught in the gears of renoviction from his apartment on Main Street. “It’s summer 2017 in Vancouver, BC, where economic imperatives are making space less and less accessible to low-income residents,” reads Nightwood’s website blurb. “The rental crisis is intensifying, ravenous real-estate development is thriving and there is a province-wide forest fire emergency blanketing the city in smoke.”

Smoke from forest fires in BC’s interior also figures in Brett Josef Grubisic’s review in The Ormsby Review, which opens:

Early in Dustin Cole’s audacious and emphatically atmospheric debut novel, Levett, Cole’s furious flaneur of an anti-hero, catches a glimpse of himself: he takes in his pouched eyes and frazzled hair. Minor indignities, they’re practically the least of his worries. For one, the weather’s intrusive and abysmal: either hostile with incessant pissing rain in Vancouver’s spring or, months later, over the summer of 2017, an ominous season of choking smoke from distant wildfires: “Through rust-coloured air, the vulcanized land evoked a planet in the hot tumult of its own creation.”

Also a book reviewer, Dustin Cole has considered books by Grant Lawrence, Grant Buday, Patrick Lane, and Brett Josef Grubisic for The Ormsby Review. — Ed.

*

The Ormsby Review: Did you always know you were going to be a writer? When you were growing up, at what point did you begin to realize that your life would entail some sort of literary pursuit?

I didn’t know I would be a writer when I was a child, but I loved making up short stories in school. I used to write these commando stories. They were pretty gnarly. My first critique was from my father. He said: “Does it have to be so violent?” Throughout my twenties and thirties a read a great deal, more and more so, until it was no longer a casual hobby. As I read and admired different authors, I liked the idea of possibly writing books, too, and then began my attempts at poetry composition and fiction writing.

The Ormsby Review: To what extent is the character Dylan Levett autobiographical? Why were you compelled to present him the way you did?

Dylan Levett is me if I followed my craziest impulses. A few of my friends couldn’t quite tell, though, and asked me if certain things Levett did were things I did. I liked this because it meant I was successful at blurring the division between documented and imagined worlds. It called into question just when exactly an ordinary event in the novel became extraordinary, or when acceptable behaviour became transgressive, and whether all of this was me or an imagined me. I’m fascinated with these categories, the way they merge together, blend, and become ambiguous or fractured. When people have conflicted responses to my work, then I know I did it right.

The Ormsby Review: Levett is a dishwasher. You seem to like writing about work. Why? And how has your working experience affected your writing?

You can choose your friends but you can’t choose who you work with. I have encountered all kinds of people on the job that I would never have encountered in my friend circles. Their personalities are different, their lifestyles are different, their values are different, their speech is different, their tastes are different. All this gave me access to varied points of view that I could borrow from, combine, and contrast in my fiction. I’m also quite interested in other people’s jobs, and will hear what people have to say about their occupation. They’ll use a lot of specialized language and include authentic details impossible to invent, which lends a distinctive texture, this naive aesthetic I’m really drawn to. So much of a person’s time is spent working. Their mind and body are tuned to a specific, often repetitive, activity they do for money. Because at least one third of our time is spent working, I think that our work lives make up a corresponding portion of our life stories.

The Ormsby Review: In BC Bookworld, Alan Twigg drew attention to your vocabulary. “Most readers don’t like to encounter words they don’t know,” Twigg wrote. “But some do. Dustin Cole caters to the latter category. Strabismic. Suspired. Weft. Corbel. Knurled. Caduceus. Plagal.” Where do you find them?! How did you justify the at times baroque language in Notice?

I will usually look up words I don’t know. That’s a way to steadily increase your vocabulary. Sometimes I see something, an object, maybe, but I won’t know what it’s called, so I’ll search it up. I’ll have to describe it in a search engine by its general appearance or constituent parts, or go to a commercial website that sells whatever it is I’m trying to find the name for. This helps sometimes with economy of prose because if you don’t know what something is called, you end up writing around what it is and wasting words you don’t need. My justification for the occasionally obscure vocabulary in Notice was based on the novel’s principal character, Dylan Levett, who is a bookish, imaginative guy, writes poetry, plays music, studied history. Sometimes these types of words occur in his thoughts, and other times they appear as free indirect discourse. By doing this, I was able to characterize Levett’s perception of the world with externally descriptive prose; it’s inside and outside his mind at the same time, and the narrator both is and isn’t Levett.

The Ormsby Review: Did you read novels when you were in high school? Is there a particular one that you loved when you were a teenager that you remember well?

I didn’t read very much in high school, but got curious about novels shortly after. I liked Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller, Herman Hesse, Hunter S. Thompson, William Gibson, George Orwell. Soon after I got into William T. Vollmann and David Foster Wallace. My reading branched out from all that and I haven’t stopped since. In his review of Notice, Alan Twigg actually recognized some of these writers in my prose twenty years after I had first read them. I found that remarkable, and remembered that Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Down and Out in Paris and London deeply impressed me as a young person. Another book that impressed me early on is Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential. I think Bourdain would’ve liked my kitchen scenes.

The Ormsby Review: What particular writers or books have most inspired you? Who are some contemporary novelists (nonCanadian is fine) you admire?

I’ve made a rule that I won’t talk about active authors who inspired me. There’s been a handful in the last few years that were game changers in terms of how I told stories and crafted images. If I said their names, it might skew how a reader engages with my work. They would be reading my book through the filter of some contemporary influence I said I had.

The Ormsby Review: What are some of the novels on your coffee table or bedside table in your home today?

I don’t have any novels going right now. Currently I’m reading Chateaubriand’s Memoirs From Beyond the Tomb, which is really enjoyable. He came of age as a noble during the French Revolution and makes some astute comments about that period. I like the way he complicates time by telling the reader when and where he is writing, what he’s doing presently while he’s recalling events earlier in his life. Or he sees patterns and repetitions in his memory. He’s critical and analytical about the perspective lost and gained by elapsed time. In addition to that, there are encyclopaedic passages and thrilling action sequences, introspective moments, and adventurous travel stories where he recounts schlepping his manuscripts through the North American wilderness and on military engagements, manuscripts that become books that later make him famous. It’s really a fine volume, I recommend it.

The Ormsby Review: You have a BA in history from SFU. How has the study of the past influenced your writing?

It made me more aware of how societies are organized, how ideas can shape events, how complex human action is, how deep and intractable the past is when you actually begin to study it. Learning history left me wanting at times, though, and that’s why I decided to write fiction instead of becoming a professional historian. I found empirical methodology quite strict, and the writing was too formally rigid. But I learned a lot. I read a lot of history and wrote a lot of essays. As a history student, I was always intentionally honing my prose style and carrying it over into creative writing. I took the knowledge, the plethora of contradictory ideas and real-world conflicts, the researching skills, the rigour, and put that all to work in service of my novel writing.

The Ormsby Review: What will Notice tell future readers (or scholars) about Vancouver in 2017? How will it stand as a document of this era?

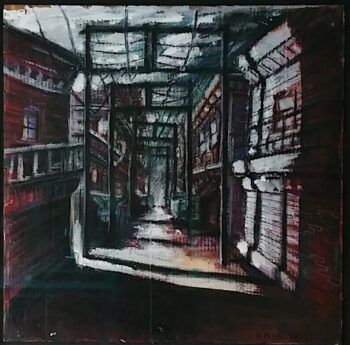

It’s impossible to know what future historians will see in something. That said, my intention was to dramatize a few personal struggles related to housing access. Perhaps a scholar in 2094 will use my novel as a primary source to make an argument about housing policy in British Columbia in the early 21st century. They might look to Notice for the representation of true subaltern experience during the housing crisis. I think the detail in Notice is granular and raw enough to give readers a sense of what it was like to physically be in East Vancouver, the Downtown East Side, and Gastown during the spring and summer of 2017.

The Ormsby Review: What part does place play in your writing?

Notice is a very place-based book. I was always around the places depicted in that book. The text is intensive that way. My forthcoming novel is a departure from place-based writing. Because Covid limited my mobility, the settings of this new novel aren’t lived, they’re imagined, even though I have been to almost every city and town depicted in the novel. I’ve thought about doing a big road trip to get more ideas for it, but I don’t think I will. It’s a personal accomplishment for me to have written a sizeable work of fiction using research and my imagination with few autobiographical elements. I’m very proud of this. And I’ve been able to re-use some of the documentarian techniques found in Notice, but instead I use them with imagined sequences. I’ve realized that these presumably disparate sensibilities aren’t that different.

The Ormsby Review: What advice do you wish you’d received, but didn’t, when you first started to take your writing seriously? And what advice would you give a writer contemplating their first novel?

It would be the same for both: Get comfortable, you’ll be here a while.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1206 Interview with Dustin Cole”