1201 Must be Bowering

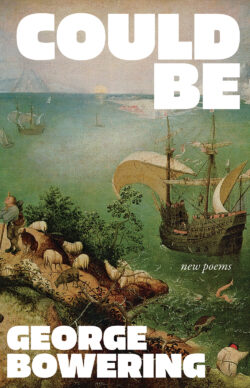

Could Be: New Poems

by George Bowering

Vancouver: New Star Books, 2021

$18.00 / 9781554201785

Reviewed by Karl Siegler

*

George Bowering, Canada’s first Poet Laureate and author of over 100 books of poetry, fiction and non-fiction, could be dead. In April of 2015, standing in front of the Point Grey Library in Vancouver, B.C., his heart stopped. If it hadn’t been for the fact that standing right beside him at the time was a 14-year-old school-girl called Ivy Zhang who had a cell-phone and knew how to use it; an anonymous passer-by who tried some CPR on him; three library employees who knew where their first aid equipment was stored and how to deploy it; two first-responders in an ambulance which arrived within minutes of Ivy Zhang’s call; and a cardiologist at VGH who recognized his condition and put him into a two week super-cooled coma before trying to revive him; he would be dead.

George Bowering, Canada’s first Poet Laureate and author of over 100 books of poetry, fiction and non-fiction, could be dead. In April of 2015, standing in front of the Point Grey Library in Vancouver, B.C., his heart stopped. If it hadn’t been for the fact that standing right beside him at the time was a 14-year-old school-girl called Ivy Zhang who had a cell-phone and knew how to use it; an anonymous passer-by who tried some CPR on him; three library employees who knew where their first aid equipment was stored and how to deploy it; two first-responders in an ambulance which arrived within minutes of Ivy Zhang’s call; and a cardiologist at VGH who recognized his condition and put him into a two week super-cooled coma before trying to revive him; he would be dead.

In the opening paragraph of this book review, there are at least eight persons, seven hyphens, and six objective circumstances standing between the contingent statement George Bowering could be dead and the definitive statement he would be dead. Everyone’s life is like that: between the possibilities of our future and the certainties of our past lies the COULD BE of our present in all of its contingencies.

George Bowering learned this from, among others, the poet and physician William Carlos Williams, whom no one would ever accuse of blind sentiment. It is therefore no accident that on the cover of COULD BE, we find a reproduction of Brueghel’s The Fall of Icarus, about which painting Dr. Williams said: “According to Brueghel / when Icarus fell / … /unsignificantly / off the coast / there was / a splash quite unnoticed / this was / Icarus drowning”. The difference I am pointing to here is, of course, that when George Bowering fell on the sidewalk outside the Library, the event did not go unnoticed, even without a splash—if it had, he would be dead.

Another thing we see on the cover of this handsome book published by New Star in June, 2021, in bright little lower-case italic script right above the spot in Brueghel’s painting where Icarus is drowning (which, like everyone else in the picture, one might otherwise not have noticed at all), are the words new poems, between the bold upper-case letters of the title COULD BE and the slightly less ostentatious spelling of its author, GEORGE BOWERING.

“Could be” is the definitive condition of being. It is the relation of space to time—what Heidegger tried to articulate in his perpetually unfinished and utterly untranslatable 1926 book Sein und Zeit. “Could be” is what drives the life of things. Without it, there could not be a future—those as yet always indeterminate things that “will be” after the past tense “there was” and the present tense “there is” are done. “Could be” is what drives the individual recognitions of proprioception as their compositional form. That’s what Bowering learned from Charles Olson: “time is the life of space.” And it’s what Heisenberg described in his famous article, also written in 1926, as a relation between an observer and the observed—active, not passive—a relationship, not an abstract principle, as it is consistently mistranslated in English. Before any of us takes a look, Schrödinger’s famous cat “could be” either alive or dead. Only what we do in time can (or will) tell. It takes time. And if, like George, we are lucky enough, when we run out of time, we get to go into overtime.

And that’s what Bowering’s COULD BE is all “about”: his extra innings in poetry since April, 2015.

He tells us so explicitly in a beautifully bracketed sequence of poems that begin with his first recognition of the birth of language within him, ‘Baby’s Breath’ and ends with the recollections of his present old age, ‘Sitting in Jalisco.’ If you are born into this world as a poet, George says, you can tell, because you suffer from an abiding pathological condition in which, from the deep dark visceral inside of you, words of a poem well up, not indiscriminately, chaotically, for you to ‘shove … back down into its container, vacuous as it may seem,’ but only and always in search of other words that will rhyme [rime] with them, until you find yourself become ‘someone you don’t even like’—where that dark someone, for example, might find ‘Oedipus, in Kelowna’ (to skip from the beginning of “Baby’s Breath” right to the end of “Sitting in Jalisco”).

In between, “The stars / fell from the sky / like similes / on a sheet of paper,” i.e., without agency. Poems write themselves. Not by the poet, but through the poet.

People and things and poems and recognitions and what Robin Blaser called “great companions” keep showing up in the extra innings of Could Be, not because of what Wordsworth famously claimed poems to be, “emotion recollected in tranquility,” but because, Bowering says: “if you could take it with you, what / would you do with it?” So you keep it in the present even though errors continue to be recognized in overtime. In “We old guys sit at our crossroads / in fear of blank spaces joining and spreading” we find in his “It Would Never Have Been a Sonnet” a perfect illustration of the dictum ‘form is never more than an extension of content.’ Of course not: the poem’s octave is missing a line. George notices such things, even though “poets have no business / looking for order.”

Poets have a duty to live on in the fields of dreams: “When Robin went into that riverside earth, / we threw books and bottles into the ground, / enough for a good long read and another round…” because “when you begin / to notice sentience floating away, you say I’ll be / a boy again, just not so much in a hurry to get there.”

A third of the way through the book, in part 3 of “Scenes from Our Balcony,” we are invited to gaze out over the sea from a castle on the Adriatic coast, there to find George’s Kerrisdale version of the opening lines of Rilke’s Duino Elegies, which in turn gave birth to his Sonnets to Orpheus: “Who, if I complained / would say go inside / and read a sonnet?”

In the Middle section of the book, ‘I Know All Those Tunes,’ we get to spend time once again with the poet’s mentors, peers, friends and relatives we think we already know so well from his many previous books, but are surprised by what re-collection adds to what we thought we already knew. Who suspected, for example, that George’s admiration for Robert Duncan’s protégé, Michael McClure, was neither diminished by the latter’s friendship with Jim Morrison of the Doors, nor his biography of Hell’s Angel, Freewheelin’ Frank? Not the kind of cool one has come to expect from a poet previously best known for the amount of serious homework he packs into his book bag. Or that he taught Brian Fawcett how to write a story; or that he’d been more interested in Roy Miki and Bobbie Creeley singing “hurtin’ songs” upstairs at the Tallman’s house while Robert was reading his grocery list downstairs in the parlour; or that Frank O’Hara’s sun would cast his shadow on “the far side, / the quiet side, the neap tide…” opening the Spicerian section ‘Combustible Paper’?

Here, the sonnet, “On the Avenue” illustrates perfectly the ambiguous caution George first articulates in the opening poem “Baby’s Breath”: “shove the poem back down into its container, vacuous as it may seem….” This certainly is one for the burn pile! As opposed to the landscapes of David McFadden’s poems which follow like a travelogue, where “The rain / falls on Ireland / like similes /on a page. / That’s what I started to say…” OK. Got it!

Then, on page 63, two thirds of the way through, we come across the poem “Could Be,” smug in thinking we’ve come to some sort of apotheosis—until we reach page 71 of course, where we are pulled up short in our comfortable certainties by George’s poem: “My Best / advice is: / don’t believe anything I said on page 63.” This is followed by the delightful silliness of poems that find themselves by accident of grammar and/or circumstance and lead us to the last section, “Pelican Dive.”

There is a temptation to read Could Be as poems of an octogenarian’s nostalgia for the expectation of beauty’s return, but George Bowering cautions us in ‘Gilbert Sorrentino,’ his homage to the great lyric poet Lorine Niedecker who wrote all her poems out in longhand: “People sometimes say, oh, I / love your book, and when I have the nerve, I’ll say / that’s not what it was written for.”

We become our own fathers in the dead heat of overtime, like Daedalus, cautioning our children against our own designs. What a gorgeous inning, George!

*

Karl Siegler is a writer and translator; the former publisher at Talonbooks; author of the Manitoba Cultural Industries Policy; three-time President of the Association of Canadian Publishers; co-founder of the SFU Centre for Studies in Publishing, The Literary Press Group of Canada, and the Association of Book Publishers of BC; and has served as board member and Vice President, Policy at the Canadian Conference of the Arts. In 2015 he was inducted into the Order of Canada for his long-term contributions to publishing. He currently lives in Powell River, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1201 Must be Bowering”

“Poets have a duty to live on in the fields of dreams”….fabulous Karl…

What a fine review, Karl. Witty and serious! Personal and transpersonal. What a tribute to George’s poetic resilience.