1184 Veterinary grace & suite

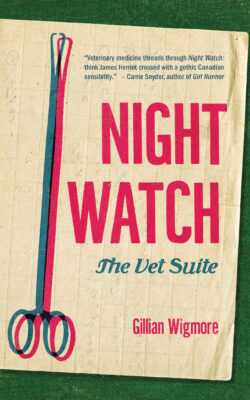

Night Watch: The Vet Suite

by Gillian Wigmore

Picton, ON: Invisible Publishing, 2021

$19.95 / 9781988784588

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

Veterinarians are absurdly villainized, unsung heroes. After my Australian Shepherd suffered THC poisoning, my respect and appreciation for veterinarians has only grown. Mercifully, Gillian Wigmore, daughter of a veterinarian, has written three novellas combined in Night Watch: The Vet Suite. Like other service-oriented professionals, vets are often accused of being money-hungry, the kind of meritless accusation that fails to account for the debilitating debt most vets are saddled with after graduating and the stress of their subsequent work. Worryingly, the suicide rate of veterinarians surpasses all other industries, and while suicide and literature are often romanticized together, veterinarians are not prominent in literature. There are no suicides in Night Watch, but there is death, rumination about life’s fragility, and a respectful and realistic understanding of veterinarians’ lives and work.

Veterinarians are absurdly villainized, unsung heroes. After my Australian Shepherd suffered THC poisoning, my respect and appreciation for veterinarians has only grown. Mercifully, Gillian Wigmore, daughter of a veterinarian, has written three novellas combined in Night Watch: The Vet Suite. Like other service-oriented professionals, vets are often accused of being money-hungry, the kind of meritless accusation that fails to account for the debilitating debt most vets are saddled with after graduating and the stress of their subsequent work. Worryingly, the suicide rate of veterinarians surpasses all other industries, and while suicide and literature are often romanticized together, veterinarians are not prominent in literature. There are no suicides in Night Watch, but there is death, rumination about life’s fragility, and a respectful and realistic understanding of veterinarians’ lives and work.

In “Love, Ramona,” the first of three novellas, Wigmore’s protagonist is Ramona, a sympathetic woman whose childhood love, Louis, mostly takes place in epistolary form after Louis moves to Quebec. She writes long, overwrought letters; he sends mix tapes she has a tendency to read into. Surely, they are meant to be together. And yet. “Love, Ramona” depicts nonlinear love, hereby defined as a romantic phenomenon adjacent to unrequited love that, unlike the former, has more warranted optimism, a love that nevertheless remains continuously quashed by circumstances and inconvenient revelations.

When Ramona becomes engaged to a veterinarian, their relationship doesn’t seem ideal; it seems adequate. To gauge whether her childhood love is one worth revisiting, Ramona and her fiancé vacation to Fiji with Louis and his girlfriend, Jessica. It’s a veritable soap opera waiting to happen, an eyeball-bursting champagne bottle. Would Ramona pass the Bechdel test? Who cares? If Ramona has platonic female friends, they certainly aren’t the focus of her life.

When Ramona and Louis first have sex — in France, as teenagers — it’s not a profound rite of passage, nor a sexual awakening. Rather, Ramona’s expectations have not been met: “… her vagina was sore. It throbbed with every heartbeat.” Louis, as heteronormativity would ordain, presumably had a better time than Ramona. Louis fixates on sunflowers and roosters, oblivious to Ramona’s vulva and emotional ambivalence. To Ramona’s credit, she is forthright: “Louie,” she said, “my vulva hurts. I don’t like beer. I’m not interested in roosters and I don’t know what the hell book you were reading that was so interesting on the bus.” On the one hand, she sounds whiny. On the other hand, when your vulva hurts, whininess is contextually appropriate. Their childhood game of naming three things — a decoy for actual conversation — is initiated without receptivity. This nonlinear love, perhaps, exists better in imagination than in real life. And what of the flawed but adequate spouse? Maybe adequacy is not pitiably dull, but actually relatively rare and something to treasure. I almost felt like the novella was, in its own way, saying, The grass isn’t always greener, motherfuckers. Sometimes it’s just grass.

In the second novella, “Bare Limbs in Summer Heat,” Celia and her fraternal twin brother, Dustin, quasi re-enact their childhood as they help a cow give birth. Though once inseparable, Celia is now a wife and a mother, like her own mother. Dustin is an earnest reader of parenting books and an earnest, unsolicited giver of said parenting books to an unimpressed Celia. Dustin is a veterinarian, like their father was. Dustin, like most of Wigmore’s characters, speaks bluntly: “There must be divine logic in the placement of the arsehole to the vagina, but I can’t figure it” (p. 62). You and me both, Dustin.

As children, Dustin and Celia helped their father’s veterinary practice. Dustin drops out of art school to become a veterinarian after he learns their father is dying and inherits the estate. Celia recalls holding a “watermelon-sized, half-full garbage bag of flesh” and feeling mortified in her high school classmate’s family barn. Gendered expectations have clearly coloured Celia’s career trajectory, veering her not towards her father’s profession but to traditionally feminine roles: “I didn’t know how, or why, but I knew it was different for a girl. Vet school was out of the question for me.”

Her empathy for the cow’s vulnerability — and reliance on a knowledgeable man — is readily apparent:

I’d always felt the cow’s part, the indignity of needing help, and I knew the potential for everything to go wrong in an instant, so the necessity of the intervention, but I also recognized the matter-of-fact invasion of the cow’s body. Like growing up a girl. Maybe that was what I meant by audacity — maybe I meant passivity when forced face-to-face with science, the lie-back-and-let-it-happen of the Pap-smear or the breast exam (p. 63).

Part of me wanted to shake Celia and ask her if she’d ever heard about the riddle where the doctor was — gasp — a woman. But Celia fulfills her gender role more than adequately; her dissatisfaction is her own best kept secret:

I told myself stories of how I mattered, that I didn’t need a vocation or a practice for my life to be worthwhile; it was obvious in the boys’ strong white teeth, in Joe’s sexual satisfaction, in the good healthy meals I cooked, that I was fine. … It strained my heart to keep up the invention, to pretend it didn’t kill me to have grown up into someone I wouldn’t want to have dinner with, let alone live with forever, when I’d thought it would all be so different. … I could pull off beautiful and well put-together for a week, or a lifetime. I could pull that shit off forever (pp. 78-79).

Celia’s relationship with Dustin reminds me of the weirdly intimate relationship between Brenda and Billy in Six Feet Under (vintage HBO unsurpassed by any show since.) Unlike Celia and Dustin, Brenda and Billy aren’t twins, but they do share the same fucked up parents — who are both therapists. Brenda and Billy continue to prioritize each other their lovers, parents, educational opportunities. Billy is parasitically dependent on Brenda, but at the same time, Brenda thrives in the useful, clear role of an enabling nursemaid. It’s only when Brenda detaches herself from Billy that she begins to acquire marks of “normal” success: a family and a career as a therapist, just like their parents.

Celia’s feelings of incompleteness are unassuaged by wifeliness and motherhood. More than anything, she wants a restoration with Dustin, her “other half” : “I never knew I’d be half a person for my whole adult life, that being a wife wouldn’t fix it and being a mother had nothing to do with it. I mourned everyday for something I’d never heard anyone else acknowledge, least of all my brother. What was this feeling but selfish and indulgent?”

Having watched arguably too much Game of Thrones — certainly, more than my feminism ought to have allowed — my first thought, less than genteelly, was: incest! “Better half” and “significant other” are common enough banalities to try to describe the outsized expectations people have of their spouses. Friendship is generally assigned a lower tier than marriage or marriage equivalents. Family might be defined as obligations with people you wouldn’t otherwise want to spend time with. And what of siblings? They see you at your worst and brattiest; they might have been your earliest teachers in how to be a human. I have a best friend who once said to me, “If I just saw my brother, I wouldn’t need anyone else.” Apart from being offended — what was I, gormlessly unflavoured tofu with carnivorous pretensions? — I could not relate in the least bit.

At one point, Dustin confesses to Celia that he wishes his wife, Shelley — a woman Celia envies, both for who Shelley is, and her closeness with Dustin — understood Dustin’s childhood the way Celia does. It’s not a long, drawn out admission; it’s brief, but potent. When society inundates you with outsized romantic expectations, the implications are often troubling. What if the most significant relationship of your life isn’t the one it’s supposed to be? What if the most significant relationship already ended in childhood?

In the third and last novella — the best one — Tom is a sleep-deprived rural veterinarian whose daily life is relentlessly animal-centric, leaving Hugh, his artist boyfriend, in the patience-waning role of The One Who Always Waits. Hugh is conflicted: “He loves his lover’s lower lip. … He has had two residences in Canada and one in Spain. He has had the opportunity of his own life. He has the opportunity of Tom, and he has the opportunity of himself. … Is this what life would always be like? Waiting, deciding, acting, not acting, waiting. Choosing? He might have made a choice. He has to make a choice … He thinks of Tom’s long throat. His future.”

Wigmore gives us multiple perspectives: Tom; his assistant, Janelle; Teapot Mountain, Janelle’s dog; and Hugh. Wigmore skillfully incorporates chapter titles as sentences, using “Hugh Makes a Sandwich” twice. To my recollection, a sandwich has never been such effective foreshadowing. Consumption notwithstanding, Wigmore gets the prize for Best Use of Sandwich. Another vignette title appears twice: “Nine Times Out of Ten,” the first of which sums up how most people feel about vets: “No one wants to call the vet. It’s too expensive. It’s not something someone budgets for. … You call the vet because you can’t handle events yourself, and no one wants to admit that.”

Teapot Mountain’s perspective is delightful:

Teapot Mountain tenderly licks the sac that used to hold his testicles. He runs his tongue over and over the bag, lining up the hairs, soaking the whole area, scrotum, shaft, penis, with all his love and attention. … He watches the man rock back and forth in his chair rubbing his head and hair. Teapot Mountain can relate — he knows how good it feels to rub.

Wigmore is also a master of consecutive sentence fragments and simple sentences, knowing exactly when to use a longer sentence to break up the deliberate minimalism: “Breakfast, maybe. Yesterday. He didn’t have lunch. He was going to, but a dog with a broken leg came in and he amputated mid-thigh.” A vignette titled “Twice in One Night” is masterfully concise and utterly unsexy: “Two prolapsed uterus calls, back to back.” Much more so than in “Love, Ramona,” the pathos in “Night Watch” lingers like a particularly tenacious palimpsest.

Hugh, a true city rat working on a Lego rendition of cow, loves Tom dearly. Nevertheless, Hugh realizes that staying and leaving are choices well within his agency. Agency, however, doesn’t mean those decisions come easily. Hugh and Janelle are linked only by Tom; they both know that Tom loves Teapot Mountain — or really, any given animal — more than either of them.

Night Watch is not set in a hyper specific era. Text messages are only mentioned a couple of times in the third novella; the Internet is neither prominent nor a character. Yet, it would be fallacious to suggest that the lack of incredibly specific digital technology indicates timelessness. As an erstwhile and erudite instructor once said, “A cup is technology. Electricity is technology.” In other words, technology is not a phenomenon restricted to pixels; pretty much everything tangible is a feat of technology. After all, technology is not synonymous, nor is it interchangeable with modernity. There are stethoscopes; there are balls being removed. Overexplanation notwithstanding, there is something reassuring about a story peopled by characters whose communications are not fraught with premeditated nonchalance via online dating. The dialogue is often crass, realistic, and wincingly earnest. People talk not for the sake of advertising their cleverness or to display pop culture knowledge; rather, Wigmore’s characters talk to convey meaning, hoping to be understood.

Wigmore doesn’t romanticize veterinarians; she writes about them realistically, respectfully, and certainly, compellingly. Loving animals is not a prerequisite for reading this book. Life is summed up concisely: “It won’t be easy, and some of it nearly kills him. But it is interesting. And sometimes in the straw and shit of a barnyard there is grace.” Indeed.

*

Jessica Poon, a writer, line cook, and pianist in Vancouver, is also now an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has also reviewed books by Meichi Ng, Alex Leslie, Zsuzsi Gartner, Robyn Harding, Brad Hill & Chris Dagenais, Lindsay Wong, Emily St. John Mandell, Sheung-King, Eve Lazarus, Annabel Lyon, Monika Hibbs, Grant Hayter-Menzies, and Wayson Choy for The Ormsby Review. Visit her website here.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1184 Veterinary grace & suite”