1174 Truth, memoir, & beautiful lies

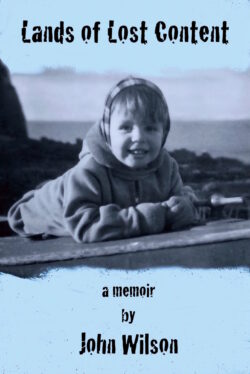

Lands of Lost Content: A Memoir

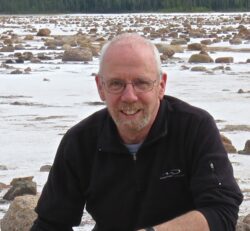

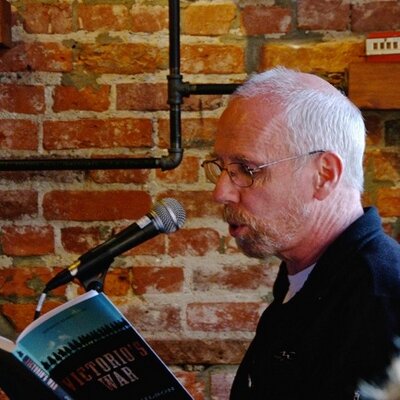

by John Wilson

Lantzville: John Wilson, 2020

$12.95 / 9780987706539 (eBook version available for $6.50)

Reviewed by Julian Wake

*

John Wilson would enjoy a story of the couple that had been married for sixty years. “I have news,” the old man said at breakfast. “Oh, what’s that, dear?” “I’m writing my autobiography.” “That’s nice. Is it about anyone I know?”

John Wilson would enjoy a story of the couple that had been married for sixty years. “I have news,” the old man said at breakfast. “Oh, what’s that, dear?” “I’m writing my autobiography.” “That’s nice. Is it about anyone I know?”

By Ginny Ratsoy’s definition (see her review of Angie Abdou’s This One Wild Life: A Mother-Daughter Wilderness Memoir), prolific Lantzville writer John Wilson has written an autobiography rather than a memoir, as he calls his Lands of Lost Content. It includes an epilogue in which he wrestles, like Abdou and Ratsoy, with the question of how much it may stray from truth. It may not be as intimate as Abdou would advocate but he would draw comfort from the ethnographic bromide that we deal in what we select, in “capta” not data. Reality being infinite, we can only echo William Blake and count on readers to see inside a grain of sand.

There is going to be a mighty season of memoirs and autobiographies as lockdowns bear fruit. How will publishers and readers choose? Serendipity will doubtless rule for most of us. Fortunately for Wilson, he throws a good hook. Most of us love a story and he is a consummate storyteller. He can elaborate on one from several directions, like a cowboy whirling his lariat in mesmerizing loops before settling on the steer he has targeted. Unfortunately, that very talent is the petard on which he hangs himself. Details of his own rich life seem prosaic in contrast to the colourful tales he finds associated with family lore and the places he has lived. He may not cook up new stories, but those he finds he researches meticulously and serves up juicily. What could compare to Dr. Elsie Inglis’s work during the Serbian resistance to Austro-Hungarian militarism, every bit as heroic as that of Dr. Bethune’s in China, and how could it have escaped the notice of mainstream historians? All the chapters invite reflection so let’s drop in on them.

Wilson sets himself a high bar by starting with the quote from Housman: do we spend most of our lives seeking the lost content of early childhood or should we count ourselves lucky for ever having known such ease and serenity? Were they a curse or a blessing? Did it make a difference that his first (“mostly unremembered”) four years of life gave him the magic of Skye, as would any of the Western Isles? Of course an autobiography never ends with the end, yet most of us surely would say we have been both hexed and enchanted in infancy. He acknowledges what might fairly be called his sister’s profligacy with the truth as she entertained their shared love of stories when she babysat him. Another older sister abetted the same tendency to create a false memory, “to improve a story,” in this case of a charmingly honest account of his first day at school.

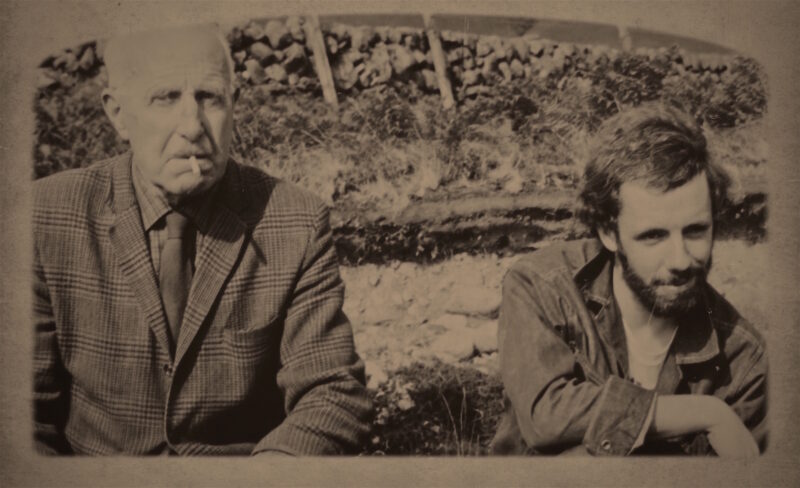

The opening four-page prologue, tellingly entitled The Seductive Liar (for him, his father’s nostalgia for the lost Raj to which he so often harks back), succinctly illustrates the cultural, political, national, and international context of the early sixties, and conjures up his own family relationships when he was nine years old. The powerful influence of his parents’ experience of, and nostalgia for, India is surely extraordinary. Very few British people actually lived there (approximately 125,000 between 1858 and 1947, at a ratio of two soldiers to one civilian). His parents, Jim and Eve, appeared to have no friends or acquaintances in the whole of the Strathclyde Region to which they went, and where Wilson spent his boyhood and adolescence. Their roles in that lost world of the Raj were modest, and yet it was as if they never adjusted to their repatriation and the loss of privileges. The rest of Britain was indifferent. He contrasts his own life with that of his parents who became used to living apart as Jim fulfilled his duties and Eve took home-leave with their children in their so class-conscious milieus, even in the fiercely leavening culture of Glasgow.

Wilson may not have heard that one of the great pleasures of being from Newfoundland or from Haida Gwaii, for example, is that you have the freedom to tell Newfie or Haida jokes. He cannot quite resist the Scottish predilection for English jokes and the tendency to point the finger south when a questionable action has occurred with full-blooded Scottish participation. Clink (as Wilson’s signifies that his father has told a joke while having a scotch and soda). He does not boast a sheep-stealer amongst his ancestors like so many self-deprecating Scottish-Canadians do, no doubt apocryphally. His pilgrimage to the sites of his parents’ lives in India is poignant. What would they have made of how the rape and slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh people during partition became attributed to British troops? (Thus is “the truth” of an urbane Chevron employee of my acquaintance, trained in journalism, in the twenty-first century, who heard and misconstrued his parents’ stories of mayhem.) Perilous indeed is the craft of storytelling. It can run amok like mobs. It is frankly refreshing to hear of Raj experience that does not dwell on crimes, excesses, and shortcomings, albeit filtered through a father’s sad recall of happier days.

Each chapter is preceded by an Interlude and sometimes by an abbreviated Haiku (or variations of three lines with no more than seven and as few as three syllables per line). The Interludes grew on me, I don’t know why, and it is not clear what they are interludes from. At first they were irritating, not great poetry yet increasingly absorbing and indicating other ways of painting storybooks. It’s grand to hear of an atheist who loves the King James Version of the thirteenth chapter of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. And how remarkable that lifelong shyness, which he began to call an “anxiety disorder,” was cured by an extemporaneous plunge onto a stage before hundreds of teenagers. Wilson’s remedy, if one is needed, to become an extravert after a lifetime of introversion is a jump into the confessional and reflective deep end.

He is hard on himself in unexpected places. He calls a novelist “a teller of beautiful lies.” On the other hand, he was surely ingenuous to take a job with the Rhodesian Geological Survey in 1975, ten years after the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) by the white supremacists. He persevered with that until the danger was in his face. “It was a strange war,” he concluded. More reflection on that, and of being “oblivious to broader political and military perspectives,” would have been welcome. He also has little to say about working for the oil sand (or tar sand) industry by way of the booming Alberta Geological Survey, which he joined in the eighties. The notorious exploitation of the inexperienced and guileless by ruthless employees in this competitive business disgusted him. Nor did the questions that an education at any university in the early seventies would raise about uranium mining exercise him. St. Andrews was, by his own account, as inclined to radical views as any other university of the day. He drew the line at anti-feminist nonsense and lost a source of income in consequence.

Wilson gambled with his wife’s blessing when he dropped his profession and turned to writing. From the start he viewed it as a craft. He has good practical advice for aspiring freelance writers. “The right horses for the right courses” was his starting policy. He acknowledges that some of his 300 articles were “suitably bland” for certain magazines that could ensure his bread and butter.

Stories of the two World Wars pervaded his upbringing. In contrast, just across the border in England, where I grew up, I never heard a word about the wars from any of the many family members who participated. Was the shame and pain so different? After reading John Wilson, I now feel I have missed something important. I will start to make up for it by looking into his And in the Morning: The Somme, 1916. It is aimed at teenagers who do not know “the code,” “the shorthand of writers” for those wartime horrors. It may suit me so long as it is not part of the banality of public violence or a crude put-down of the honourable profession of soldiering and protecting, and of deterring aggression. At worst I may learn why professional historians are aghast at the very concept of historical fiction. But after reading Lands of Lost Content, I am confident of better. I am certain that in John Wilson’s hands the pitfalls of playing with truth are avoided and the dilemmas and paradoxes are fairly portrayed.

*

Born in the UK of Welsh, English, and Scottish ancestry, Julian Wake came to Vancouver in 1966 to study forestry at UBC. He switched fields and earned BA and MA degrees in social anthropology. He has lived a countercultural life in the Kootenays and worked in multiple capacities for many First Nations in several areas of British Columbia, and in developing countries including Nepal, Jamaica, and Peru. Julian lives in Ganges on Salt Spring Island. Editor’s note: Julian Wake has also reviewed books by Robert Hutton and Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1174 Truth, memoir, & beautiful lies”