1166 Canadian poetry: the untold story

Little Resilience: The Ryerson Poetry Chap-Books

by Eli MacLaren

Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020

$37.95 / 9780228003496

Reviewed by Carole Gerson

*

We have long needed this book! For 35 years, from 1925 to 1960, Canadian poets writing in English were sustained by the Ryerson Poetry Chap-Book series, which issued some 200 booklets by 144 different writers. Most were one-time authors, although a handful published three or four titles, and over half were women. While the press was based in Toronto, its authors and audience extended across the country. Some contributors, such as Maritimers Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman, were already well-known when their first Chap-Books appeared but most were not, although several rose to prominence. Among the stars of the series were three BC women who are focal points in this study: Anne Marriott, M. Eugenie Perry, and Dorothy Livesay.

We have long needed this book! For 35 years, from 1925 to 1960, Canadian poets writing in English were sustained by the Ryerson Poetry Chap-Book series, which issued some 200 booklets by 144 different writers. Most were one-time authors, although a handful published three or four titles, and over half were women. While the press was based in Toronto, its authors and audience extended across the country. Some contributors, such as Maritimers Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman, were already well-known when their first Chap-Books appeared but most were not, although several rose to prominence. Among the stars of the series were three BC women who are focal points in this study: Anne Marriott, M. Eugenie Perry, and Dorothy Livesay.

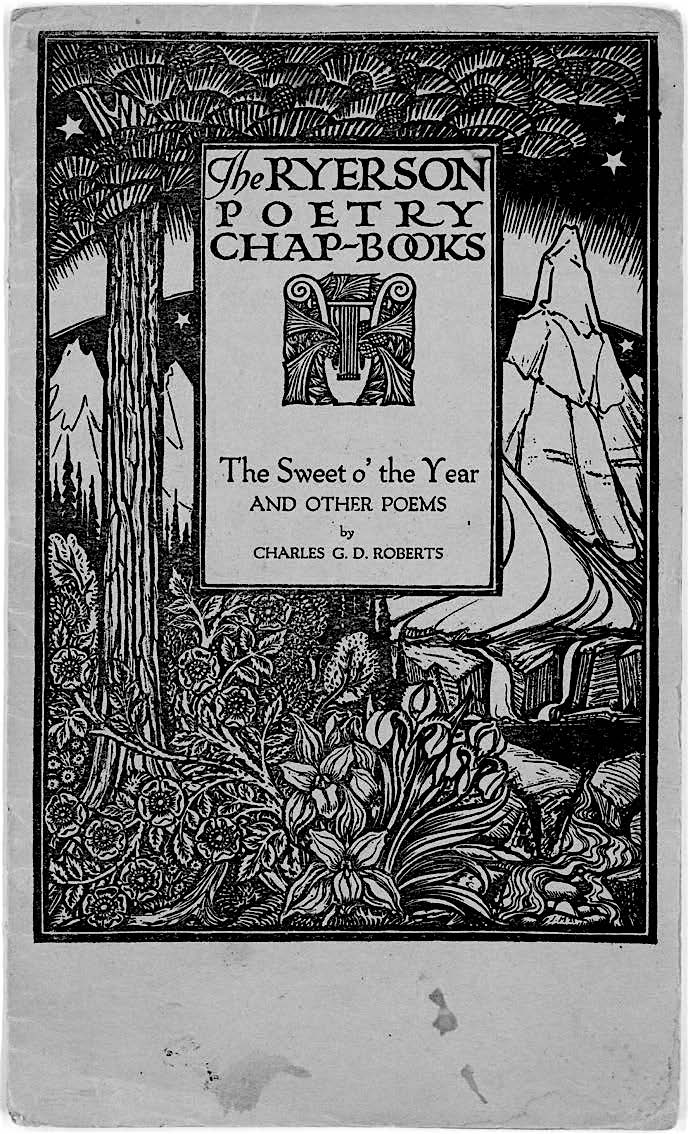

For the most part, the Chap-Book writers were occasional littérateurs who were passionate about poetry and were prepared to receive free copies in lieu of royalties or to contribute financially towards the production of booklets of eight to twenty-four pages that were issued in print runs of 250 to 500. Their price began at 50 or 60 cents, rising to one dollar in 1950. Most Chap-Books were graced by the same woodcut cover image of selected elements from the Canadian landscape created by J.E.H. Macdonald, a member of the Group of Seven who often worked for publishers, and updated in 1942 by his son, book designer Thoreau Macdonald.

Drawing on years of expert archival research, Professor MacLaren provides considerable contextual information about Canadian literary publishing in the first decades of the twentieth century and tabulates details about the size and terms of production of every Chap-Book. This series represented the commitment of Lorne Pierce, editor at Ryerson Press from 1920 to 1960, to Canadian writing and Canadian publishing at a time when American domination forestalled the serious production of Canadian books. (For the full story of Lorne Piece, see Sandra Campbell’s superb biography, Both Hands: A Life of Lorne Pierce of Ryerson Press, published in 2013.)

Each Chap-Book had to meet with Pierce’s approval as he personally supervised the process of selection and production. His preference for romantic nationalism helped shape the ethos of mid-twentieth-century middlebrow Canadian literary culture, while his social gospel orientation and desire to portray life in Canada with a degree of realism allowed for advocacy on behalf of the marginalized and the downtrodden.

For the most part, the Chap-Book poets were disparaged by the modernist cultural arbiters who dominated the critical scene as Canadian Literature became established as a valid scholarly field during the second half of the twentieth century. MacLaren reassesses the significance of these poets as enthusiasts who believed in a Canadian literature and nourished the cultural mainstream out of which innovation would arise. Moreover, as he follows the series’ development, he evaluates it as a whole, showing how “Dreamy beauty and cutting realism accumulated as the series grew over three and a half decades, with no clear break between the two. Convention and experimentation drifted through the same print-cultural field, competing with and pollinating each other” (p. 204).

Hence the few mid-century Chap-Book authors whose work now appears to signal abrupt innovation – most notably Anne Marriott and Dorothy Livesay – were congruent with the overall aim of the series, rather than exceptions. To quote MacLaren again, “Gradually, the accumulating Chap-Books approached a parliamentary inclusivity that brought together the nation’s diverse poetic voices to an admirable and unprecedented, if always imperfect, extent” (p. 242), thereby creating a space in which both romanticism and modernism could thrive. By the 1950s, the series included many poets who would soon become more prominent as modernists such as Louis Dudek, Milton Acorn, Elizabeth Brewster – and even Leonard Cohen, whose “Song to Make Me Still” appeared in the McGill Chapbook of 1959, one of the series’ few multi-authored volumes.

To illuminate the balance that he finds in the Chap-Books, MacLaren offers detailed case studies that show the importance of the series to five poets, two of whom represent the romantic mainstream and receive scant attention today (Nathaniel A. Benson and M. Eugenie Perry), and three of whom have been canonized as modernist innovators, namely Marriott, Livesay and Al Purdy. With Benson, who lived in Toronto, and Perry, who lived in Victoria, we see how their careers were supported by Chap-Book publication and how they in turn promoted the series, with Perry sharing not only Pierce’s literary taste but also his sympathy with the hard-of-hearing – one of Perry’s major concerns – as his own deafness increased.

Victoria-based Anne Marriott was the star of the Ryerson Chap-Books. Thanks to the nurturing of J.F.B. Livesay – Dorothy’s father, who promoted the writings of his daughter and her peers – Marriott’s career was jump-started with The Wind Our Enemy (1939), her first Chap-Book and also her first significant publication. This long poem’s stark description of the prairie dust-bowl remains her best-known work, canonized as an exemplar of Depression-era realism. Her second Chap-Book, Calling Adventurers! (1941), would be the only Chap-Book to win the Governor General’s Award for poetry, thereby enhancing the series’ credibility. It was soon followed by her third, Salt-Marsh (1942). Each of these publications earned Marriott less than $12 apiece; their value lay in their cultural capital, not their economic return.

Dorothy Livesay’s relationship with the Chap-Book series was quite different. She had earned two Governor General’s Awards for larger poetry collections published by Ryerson during the 1940s before issuing her only Chap-Book, Call My People Home (1950), her documentary poetic drama that sharply critiqued the Canadian government’s internment of Japanese-Canadians during the Second World War and demonstrated that “Canadian poetry could be at once lyrical and leftist” (p. 175).

Little Resilience was chosen by the Association for Canadian and Quebec Literatures (ACQL) as one of three finalists for the 2020 Gabrielle Roy Prize, which each year honours the best works of Canadian literary criticism published in English and in French. While another title won the prize, this nomination recognized the significance of MacLaren’s excellent study in showing how mid-twentieth-century English-Canadian literary culture flourished under challenging circumstances and laid the groundwork for the writers of the 1960s whose names remain familiar today.

*

Dr. Carole Gerson (FRSC) is Professor Emerita in the English Department at Simon Fraser University. Co-editor of volume 3 (1918-1980) of History of the Book in Canada / Histoire du livre et de l’imprimé au Canada, she has published extensively on Canada’s literary and cultural history with a focus on early Canadian women writers, from well-known figures such as Pauline Johnson and L.M. Montgomery to more obscure figures who can be found in her two databases: Canada’s Early Women Writers and the more inclusive Database of Canada’s Early Women Writers. In 2011, her book, Canadian Women in Print, 1750-1918, won the Gabrielle Roy Prize for Canadian criticism. In 2013 she received the Marie Tremaine medal from the Bibliographical Society of Canada. Her most recent book, co-authored with Peggy Lynn Kelly, is Hearing More Voices: English-Canadian Women in Print and on the Air, 1914-1960 (Ottawa: 2020), reviewed here by Phyllis Reeve. Editor’s note: Carole Gerson has previously reviewed One Madder Woman, by Dede Crane, for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1166 Canadian poetry: the untold story”

Thanks, Carole Gerson, for – in this review and in your own work – refusing to let Canadian writers of the past just fade away.