1148 Morality, poison & infanticide

The Trial of Jeanne Catherine: Infanticide in Early Modern Geneva

by Sara Beam

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021

$24.95 / 9781487587673

Reviewed by John Lepage

*

Historians are usually careful to establish the relevance of their publications. It is part of the ongoing program of history’s defence of itself as a field of study to a world often doubtful or cynical about learning from the past. Perhaps the subject matter of this book by Sara Beam, a history professor at the University of Victoria, seemed so self-evidently relevant that she decided to forgo the expected justification. Indeed, the book’s subject matter does seem relevant. It touches on domestic life in the early modern period, women’s history, religious history, class, medicine, and forensic analysis, all subjects of importance in our time. Moreover, the book makes a marked contribution to the field of document history. It contains a full transcription of the case notes and correspondence of legal investigators in Geneva during the 1686 trial of Jeanne Catherine Thomasset, an unwed noblewoman, for the murder of her own two-year-old daughter and the five-year-old son of the peasant woman who had looked after and wet-nursed her child from birth.

Historians are usually careful to establish the relevance of their publications. It is part of the ongoing program of history’s defence of itself as a field of study to a world often doubtful or cynical about learning from the past. Perhaps the subject matter of this book by Sara Beam, a history professor at the University of Victoria, seemed so self-evidently relevant that she decided to forgo the expected justification. Indeed, the book’s subject matter does seem relevant. It touches on domestic life in the early modern period, women’s history, religious history, class, medicine, and forensic analysis, all subjects of importance in our time. Moreover, the book makes a marked contribution to the field of document history. It contains a full transcription of the case notes and correspondence of legal investigators in Geneva during the 1686 trial of Jeanne Catherine Thomasset, an unwed noblewoman, for the murder of her own two-year-old daughter and the five-year-old son of the peasant woman who had looked after and wet-nursed her child from birth.

The transcription is prefaced by a contextualizing introduction presenting information the author deems appropriate to a fuller understanding of the case. Laid out in this way, the material may well serve as a useful basis for other historians’ case-study analyses. Beam advances no analysis of her own, possibly by design, though she does not indicate as much. Nor does she say who the book’s audience is or how that audience might benefit from studying the transcription. She contents herself with general observations and caveats such as this:

People who study communities different from their own, whether distinguished by time, by place, or by other markers such as race/ ethnicity or class, have long since understood that a person’s sense of themselves is specific to their lived experience, which in turn is profoundly shaped by the stories told to them throughout their lives to make sense of the world. Our dynamic understanding of who we are and how our lives are meaningful are expressed through stories, told to us and told by us to friends/ family, to employers/ judges, to sacred persons/ places, to ourselves. How individuals in Catherine’s world understood themselves as good or bad people and the scripts to which they tried to fit their experiences need to be investigated and not assumed (p. 3).

This emphasis on story, ever so slightly inflected with academic moralism, sounds a lot like the kind of context-setting indulged in by literary scholars, and it is possible Beam intends the book to be a value-system blank canvas, primed to be completed by readers in just the way that fiction has been read and interpreted for millennia.

Nevertheless, I feel the book needs to be more forthcoming about its audience and purposes, not to mention the author’s perspectives on the case. Beam’s desire not to prejudice readers may be laudable, but those who choose to read the book need some guidance, and what background information the author provides in the introduction would profit from greater contextualizing background of its own. For example, it would be useful to understand on what basis the author has chosen to provide or withhold information. In short, what must readers know to conduct an informed reading of the trial of Jeanne Catherine?

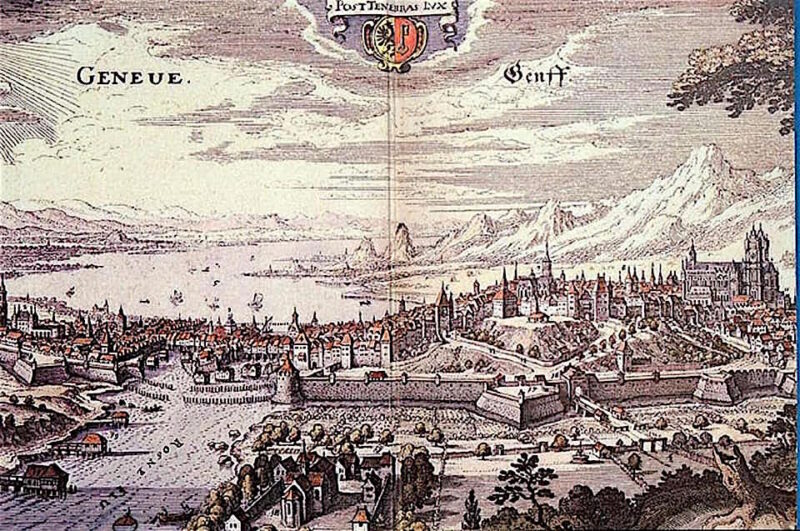

The introduction unfolds teasingly like the skin of an onion, providing information on the religion, politics, and social life of Geneva and by turns mingling it with related evidence from the trial. Only at the third mention is it revealed that Geneva was an autonomous republic engaged in a dynamic relationship with the regions outside its walls and jurisdiction. Is it necessary to say that, “Like other Christian denominations, the Reformed Protestant church upheld the central doctrine of Christianity, that the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, son of God, when he was crucified by the Romans, allowed for the possibility of eternal salvation for all faithful Christians” (p. 12)? Probably not. Some sense of a primary audience, as I have said, and of the book’s intended role in the study of history, would have helped Beam make more judicious choices and, not incidentally, given readers a greater sense of assurance and purpose in approaching the material.

The book’s subtitle points to infanticide as its primary moral concern. The transcription and Beam’s introduction make it clear, however, that poisoning attracted greater social stigma in Geneva, in addition to playing a more pronounced role in the trial. The publisher may have recommended the eye-catching title as appealing to a wider readership. I can imagine a market for the book, seduced by its title, in undergraduate courses on women’s history and women’s studies, gender and social studies, criminology, and some other disciplines. The introduction and the explanatory notes are pitched to a general, less well-informed audience and may prove more of an irritant than an aid to experienced scholars.

The real value of this book lies in the transcription, as translated by Beam, who is to be commended for bringing it into print. It offers rare insight into the thinking processes of people involved in a criminal trial three and a half centuries ago, as well as glimpses of the lives of real people trying to represent themselves honestly, or to their own advantage, before the law. The transcription raises all sorts of intriguing questions. It presents a compelling mystery of sorts, and I suspect this was the reason for Beam’s initial interest in the trial. It must have read to her like a crime novel, in whose pages Jeanne Catherine is revealed to have had unmarried relations with a “stranger” — someone she either cannot or will not identify, suspected by the investigators to be her cousin — and, after having given birth to an illegitimate daughter, has farmed her off to the countryside – perhaps to keep her birth a secret, perhaps as a preliminary step to giving her up for adoption — only to return two years later and poison her and another child for no discernible reason and to all appearances without remorse. Altogether, the vivid, real-life drama and the mysteries it presents are compelling enough to justify the reading.

*

Until his retirement in 2019, John Lepage was a professor in the English Department and former Dean of Arts (1999-2006) at Vancouver Island University. He has a BA from McGill University and a PhD from the University of Glasgow. Among his publications is The Revival of Antique Philosophy in the Renaissance (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster