1144 Belcourt’s Two-Spirit journey

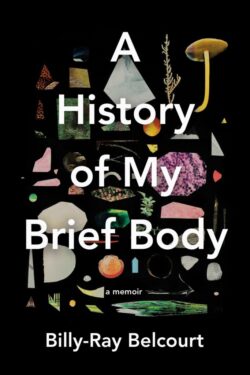

A History of My Brief Body: A Memoir

by Billy-Ray Belcourt

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Hamish Hamilton), 2020

$25.00 / 9780735237780

Reviewed by David Milward

*

The term Two-Spirit is used in many contemporary Indigenous communities to describe Indigenous persons whose personalities and spirits may have both feminine and masculine aspects. Many Indigenous people suggest that the term itself goes back generations, and historically proves that many Indigenous cultures were tolerant of their members having homosexual orientations.[1] A key endeavour of A History of My Brief Body, by Billy-Ray Belcourt — Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia and a member of the Driftpile Cree First Nation — is to show how forces of colonialism, racism, and homophobia have worked together to erode that historical tolerance to a very real degree. And Belcourt uses more than one analytical lens to convey that message.

The term Two-Spirit is used in many contemporary Indigenous communities to describe Indigenous persons whose personalities and spirits may have both feminine and masculine aspects. Many Indigenous people suggest that the term itself goes back generations, and historically proves that many Indigenous cultures were tolerant of their members having homosexual orientations.[1] A key endeavour of A History of My Brief Body, by Billy-Ray Belcourt — Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia and a member of the Driftpile Cree First Nation — is to show how forces of colonialism, racism, and homophobia have worked together to erode that historical tolerance to a very real degree. And Belcourt uses more than one analytical lens to convey that message.

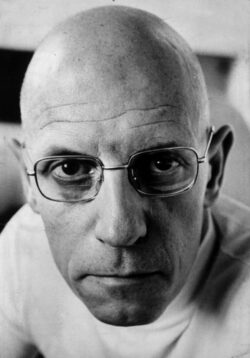

French philosopher Michel Foucault is perhaps not well known outside of academic circles. But his passing away in 1984 has not diminished his enduring status as an immortal influence across a multitude of academic disciplines. He invited his audience to imagine the human body not so much a physical entity but as a social construction. The body is the subject of the state’s evolving responses of punishment and regulation. The bodies of individuals become tools for social engineering by the state. The body becomes a site of power dynamics such as contestation, negotiation, and even acquiescence as society and its individuals work out a social contract. There can be enduring stability and acceptance. But there can also be oscillation, contestation, and realignments when power relationships adjust themselves. Power is not so much a possession as a productive process and a constant exercise. And these power dynamics can occur daily in ways that do not manifest in the obvious passing of state legislation.[2]

Foucault’s ideas have been adapted by numerous scholars — but in ways that serve their particular interests. And Belcourt has his own unique ways of drawing on Foucault, whose theories have been used by numerous scholars to dissect the power dynamics of colonialism and examine how post-colonial societies have tried to adjust to undoing the damaged legacy left by colonization.[3] Belcourt spends a great deal of energy in A History of My Brief Body in exploring how Indigenous bodies have been and continue to be sites for the exercise of Canadian colonial power. For example, he examines historical colonialism against Indigenous peoples in the form of Indian Act provisions that confined Indigenous peoples to reservations or compelled Indigenous children to attend residential schools. And the residential schools themselves marked the most naked and repressive use of colonial power against Indigenous bodies. But Belcourt is emphatic that colonialism is not a thing of the past. He cites the infamous case of Colten Boushie’s murder by Gerald Stanley, and Stanley’s acquittal during the subsequent murder trial. The trial marks the exertion of colonial power against Indigenous bodies by devaluing them. These critiques also draw on Critical Race Theory, the idea that law and politics are inherently embedded with racism against underprivileged racial minorities. Belcourt’s work shows overlap between Foucault and Critical Race Theory. As a colonial state, Canada constructs Indigeneity in ways that serve it own interests and that marginalize Indigenous peoples themselves.

Foucault’s ideas have also been used by feminists, with women’s bodies and female sexuality (in any orientation) seen as sites of gendered power struggles.[4] Belcourt engages in a similar exercise, but in ways that overlap with another analytical lens, intersectionality, which was conceived by Black female scholars as a kind of uneasy marriage between Critical Race Theory and feminism. Early intersectional works sought to expose the multiple layers of oppression faced by Black women that leave them underprivileged in comparison to almost everyone else around them. White women may certainly be underprivileged compared to White men, with fears of sexual violence, workplace discrimination, and societal expectations that still leave the bulk of household duties on women. Black men may be underprivileged compared to White men, and perhaps even most White women, due to enduring racism in mainstream society. Black women, however, not only have to worry about racism, but also fears of sexual violence, domestic violence, desperate poverty and social isolation. And those travails are frequently visited upon them by Black men.[5]

Belcourt indicates quite early in A History of My Brief Body that he often felt stigmatized among his relations and his community for being homosexual. And he squarely blames colonialism for introducing a homophobic heteronormativity among Indigenous peoples in contrast to the historical tolerance for Two-Spirit people. Belcourt is thus applying an intersectional lens that is distinctive to his experience as an Indigenous gay man.

And he continues that theme with numerous descriptions of his sexual encounters with other men. The exercise may come across as self-indulgent to some readers on the surface, but it does have a purpose. Belcourt’s own body is a site for power struggles. Overlapping forces of heteronormativity and colonialism and racism are trying to exercise power over his body. His consensual experiences with other men amount to Belcourt trying to assert personal autonomy over his body, and to resist those manifestations of power of which his body is a site, a contested terrain.

I will say that A History of My Brief Body was a fascinating read, but I do have to raise two points of concern. One is accessibility. Belcourt often writes in poetic prose, and in a quite personal and emotional style, but that in itself is not the concern. Because his narrative frequently bounces from one theme to the next, following him requires the reader to give his text a high degree of attentiveness and effort. This narrative discontinuity combined with Belcourt’s theoretical lenses make me wonder about the book’s accessibility to some of his audience, who may not have previous familiarity with weighty analytical frameworks like those of Foucault and intersectionality.

My other point of concern is that Belcourt describes several of his sexual encounters with a very explicit level of detail. Lest I be taken for being homophobic, I can honestly say that I would be raising this point if the level of detail were about heterosexual encounters as well. To be fair, Belcourt would not be driving home the points that he wants to without going into that level of detail. My point is that there are erotic literary genres, with some subgenres focusing on themes like BDSM or homosexuality, where explicit levels of detail are staples. Belcourt, by the way, readily indicates a familiarity with those genres. But the audiences for them are self-selecting: readers know what they are getting into before they open the cover to the first page. A mild concern I have is that readers expecting social commentary or academic theorization (which are indeed in the book), or who have other expectations, may find some of Belcourt’s themes and level of detail a bit jarring. Despite these cautions, A History of My Brief Body is hard-hitting, passionate, and certainly worth a read.

*

David Milward is an Associate Professor of Law with the University of Victoria, and a member of the Beardy’s & Okemasis First Nation of Duck Lake, Saskatchewan. He assisted the Truth and Reconciliation Commission with the authoring of its final report on Indigenous justice issues, and is the author of Aboriginal Justice and the Charter: Realizing a Culturally Sensitive Interpretation of Legal Rights (UBC Press, 2013), which was joint winner of the K.D. Srivastava Prize for Excellence in Scholarly Publishing and was short-listed for Canadian Law & Society Association Book Prize, both for books published in 2013. David is also the author of numerous articles on Indigenous justice in leading national and international law journals. Editor’s note: David Milward has also reviewed books by Christa Couture, Darryl Leroux, Bob Joseph with Cynthia F. Joseph, Elspeth Kaiser-Derrick, David B. MacDonald, and Darrel J. McLeod for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Brian Joseph Gilley, Becoming Two-Spirit: Gay Identity and Social Acceptance in Indian Country (Omaha: University of Nebraska, 2006).

[2] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977); Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-1978 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2008).

[3] Jane Hiddleston, Understanding Postcolonialism (Stocksfield, United Kingdom: Acumen Press, 2009).

[4] Margaret McLaren, “Foucault and the Subject of Feminism” (1997) 23:1 Social Theory and Practice 109.

[5] Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color” (1991) 43:6 Stanford Law Review 1241.

3 comments on “1144 Belcourt’s Two-Spirit journey”

Regarding your “points of concern,” Professor Milward, might “accessibility” also refer to the bloodstream poetry supplies to theory, bringing unfamiliar readers with it? Might “explicit” depictions of sexual relations moisten the contours of theory’s so-called dry and distant texts?

I can see that. I’m well aware that “mileage may vary” very often comes into play with anything anybody reads.