1120 East Kootenay guide outfitter

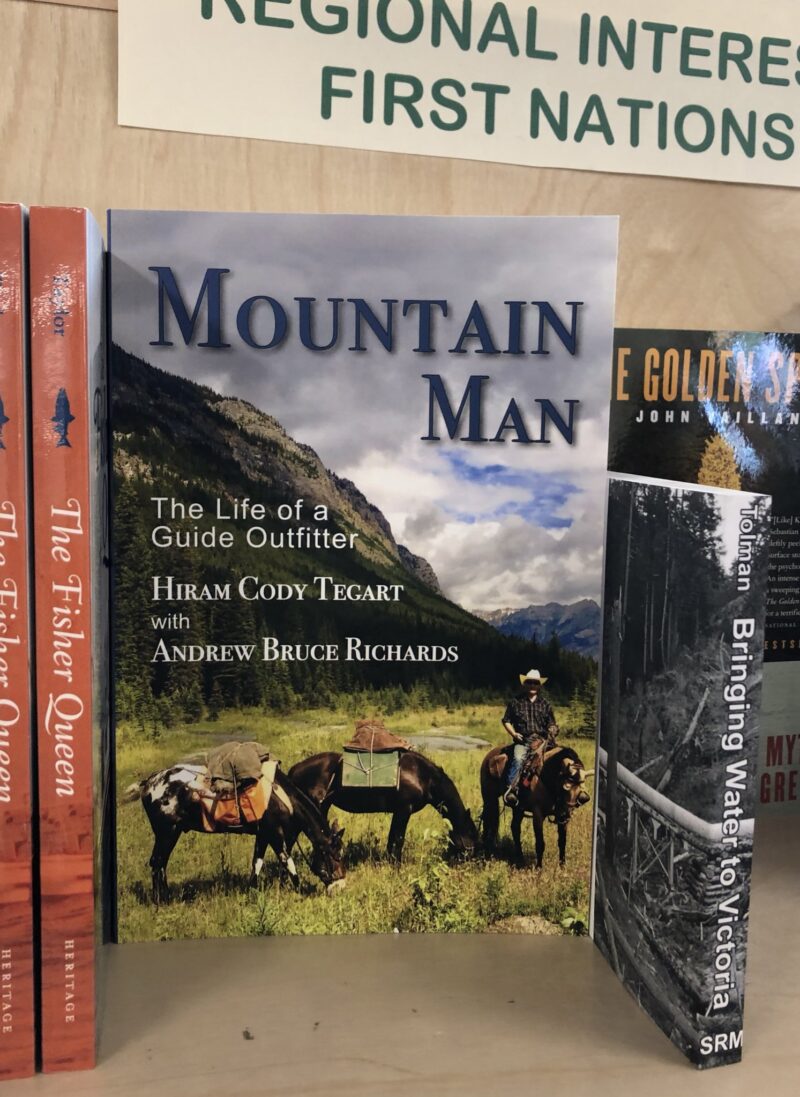

Mountain Man: The Life of a Guide Outfitter

by Hiram Cody Tegart with Andrew Bruce Richards

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2019

$24.95 / 9781773860060

Reviewed by Sage Birchwater

*

Mountain Man: The Life of a Guide Outfitter by Hiram Cody Tegart with Andrew Bruce Richards takes us to another place and time. The East Kootenays in the late 1960s, like many backwoods places in British Columbia, was wild and unfettered. Game populations were vibrant; elk numbers were increasing; mule deer, moose and caribou shared habitat in equilibrium with grizzly and cougar. The logging industry was only beginning to poke and pry into otherwise impenetrable habitats. For Cody Tegart and his large extended family of hunters, trappers, ranchers and loggers, the romance of the hunt was rich upon the land.

Mountain Man: The Life of a Guide Outfitter by Hiram Cody Tegart with Andrew Bruce Richards takes us to another place and time. The East Kootenays in the late 1960s, like many backwoods places in British Columbia, was wild and unfettered. Game populations were vibrant; elk numbers were increasing; mule deer, moose and caribou shared habitat in equilibrium with grizzly and cougar. The logging industry was only beginning to poke and pry into otherwise impenetrable habitats. For Cody Tegart and his large extended family of hunters, trappers, ranchers and loggers, the romance of the hunt was rich upon the land.

At any point in time it’s easy to forget that the natural world, like the geopolitical human landscape, is dynamic and in a constant state of flux. Snapshots in time don’t tell the whole picture. They only show the lay of the land at a particular moment in history.

In 1969, 16-year-old bespectacled Andy Richards, a skinny newcomer kid from the prairies, was befriended by 18-year-old Cody Tegart at David Thompson Secondary School in Invermere, BC.

“I was trying to fit into the greaser group,” says Richards, “and Cody pulled me into the cowboy fold. There were the jocks and the cowboys at the top of the scale, followed by greasers, nerds and hippies.”

Cody was the son of Doreen and Jim Tegart, local ranchers who ran a successful guide outfitting business. They were a pioneering family that got established in the Columbia Valley in 1886. “They were rough-hewn, hard-working folks who, through a lot of prolific breeding, helped populate an underpopulated valley,” Richards says.

Over the next half dozen years Richards, Tegart and Cody’s younger brother, Garrett, and a few other young friends, did what teenage boys becoming men were prone to do in the early 1970s. “Life was a whirlwind of playing hooky from school for impromptu fishing trips, weekend cruising in our various cars, and looking for bush parties with our ever-present bootlegged case of beer.”

In summer they worked on occasional guide trips on horseback, and spent countless hours and days cutting trail in the hunting territory. Their daily activity was accented by the spectacular backdrop of the Rocky Mountain wilderness.

In a few short years the young men all went their separate ways. Richards headed off to the city with the love of his life, “my brown-eyed girl,” and he carved a distinguished career as a journalist. Only Cody remained behind to embrace the only way of life he knew and loved.

After a brief introduction to the book, Richards passes the torch to Tegart to tell his own story about growing up in the mountain environment where formal schooling was never his friend. Wild and woolly adventures were always in abundant supply. He taught himself to swim by pushing a log around a pond; graduated to dog paddling, then actually swimming. To perfect his technique he’d jump in the Kootenay River at high water, with or without the current.

In 1979 at 28 years old, Tegart took over his dad’s guiding and hunting operation in the Palliser River watershed. The timing was perfect and his business flourished as elk were getting re-established in the region. His hunters from across the world invariably filled their tags and returned home with their trophies.

By the mid-1990s however, the abundance of game had become depleted. Elk populations that had grown from obscurity and peaked in the 1980s, had plummeted. Apex predators like grizzly and cougars were joined by wolves, which contributed to the decline. Commercial logging opened access into previously impenetrable habitat. Political whim, influenced by an urban bias opposed to predator reduction measures to spare the game populations, was the final nail in the coffin.

Tegart saw the writing on the wall and in 1995 sold his guiding area. He stayed on for two more years to help run the business. After that he guided for other outfitters.

Richards and Tegart lost touch with each other for two decades then reconnected at a funeral in the Columbia River Valley. Somewhere along the way they decided to collaborate on a book to capture this vanishing way of life. Unfortunately Tegart died in 2018, before the book was complete.

Richards was determined to stay with the project to ensure Tegart’s story would be told. He added the recollections of others who knew Cody and hunted with him. He also included the narrative of retired game biologist Bob Jamieson who was instrumental in helping create Height of the Rockies Provincial Park in 1995, to preserve remnants of habitat from the chainsaw and feller buncher.

Both Richards and Jamieson say decades of government bungling and mismanagement of both habitat and wildlife contributed to the decimation of elk herds and moose.

Jamieson offers a biologist’s perspective on the decline of the elk population. He says calf recruitment is the process where young calves come into the population each year to replace the older cows and bulls that die. “A herd needs twenty-five to thirty calves per 100 cows surviving their first year to keep the population stable. If the ratio is less than that the herd will collapse.”

Jamieson says the decline in elk calf survival coincided with a marked increase of all four large predators in the region, grizzly bear, black bear, cougar and wolves. This resulted in high calf mortality. He isn’t confident that wildlife and especially elk will continue to be a part of the landscape or culture of the East Kootenays. The big loss, he laments, will no longer being able to hear the bugling call of bull elk on late September frosty nights.

Richards and Jamieson put forward the argument that environmental/anti-hunting groups are misguided.

Obviously the human attitude toward wildlife management has shifted. The glory days of the trophy hunt has slipped into obscurity. Jamieson notes that poisoning wolves was common practice in the 1940s due to a rabies scare, and this accounts for the scarcity of wolves until the 1990s. Baiting grizzlies with dead horses was also considered fair game as recently as the 1970s. However, in 2017 as a reflection of the shifting times and change in attitude, the provincial government eliminated grizzly sport hunting in British Columbia altogether.

Jamieson argues that when grizzlies are no longer hunted, they lose their fear of humans:

We’ve traded healthy populations of elk, sheep, moose, mule deer, goats and some grizzlies, black bears and a few cougars and very few wolves, for a system with no elk, very few moose, almost no mule deer, some goats, a few bighorn sheep, and just enough whitetails to maintain a low-level population of cougars and wolves.

Get tough or die, was Cody Tegart’s rallying cry. He also had a gentle heart.

“Cody taught me so much about being fearless in those early years,” Richards remembers. “He constantly pushed me beyond my comfort level.”

One Christmas shortly before he died, Cody called up Richards to talk about the book. Then just before he hung up he blurted, “I love you guys!”

Richards recalls that in their younger days they were too tough to say stuff like that.

And so marks another snapshot in time some fifty years later.

*

As a long-time resident of the Cariboo-Chilcotin, Sage Birchwater has written several books about the area including Chiwid (New Star, 1995). Born in Victoria in 1948, Birchwater was involved with Cool Aid in Victoria, travelled throughout North America, and worked as a trapper, photographer, environmental educator, and oral history researcher. Sage served as the Chilcotin rural correspondent for two local papers for 24 years while raising his family south of Tatla Lake. He has also lived in Tatlayoko, where he was a freelance writer and editor, and Williams Lake, where he was a staff writer for the Williams Lake Tribune until his retirement in 2009. His other books include Williams Lake: Gateway to the Cariboo Chilcotin (2004, with Stan Navratil); Gumption & Grit: Extraordinary Women of the Cariboo Chilcotin (Caitlin, 2009); Double or Nothing: The Flying Fur Buyer of Anahim Lake (Caitlin, 2010); The Legendary Betty Frank (Caitlin, 2011); Flyover: British Columbia’s Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2012, with Chris Harris); Corky Williams: Cowboy Poet of the Cariboo Chilcotin (Caitlin, 2013); and Chilcotin Chronicles (Caitlin, 2017), reviewed here by Lorraine Weir. Editor’s note: Sage Birchwater has also reviewed books by Chris Czajkowski & Fred Reid, Marianne Van Osch, and Jay Sherwood for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1120 East Kootenay guide outfitter”

Interesting looking books.