1115 An artist in the wreckage of war

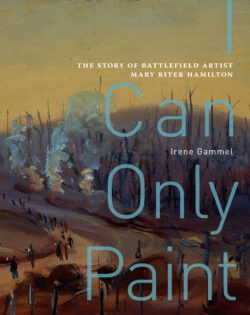

I Can Only Paint: The Story of Battlefield Artist Mary Riter Hamilton

by Irene Gammel

Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 2020

$49.95 / 9780228003915

Reviewed by Robert Amos

*

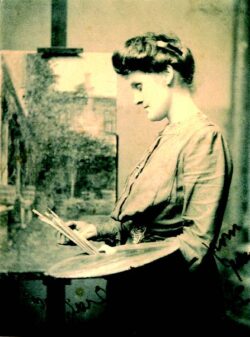

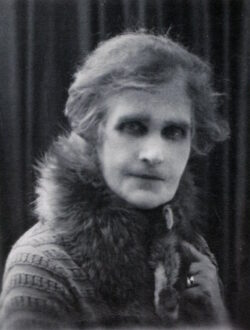

Mary Riter Hamilton was a Canadian artist born in Culross, Ontario in 1867. Following a difficult childhood she was married at 21 and widowed at 26. She was then able to pursue art training in Toronto, following which she managed to travel to Europe. There she studied and painted in Germany and France from 1901 to 1911. As one of a throng of expatriates, she gained a certain reputation in the Salons of Paris, creating traditional works for display. Though well painted, these were a notch below the skillful canvases of her Victoria contemporary Sophie Pemberton.

Mary Riter Hamilton was a Canadian artist born in Culross, Ontario in 1867. Following a difficult childhood she was married at 21 and widowed at 26. She was then able to pursue art training in Toronto, following which she managed to travel to Europe. There she studied and painted in Germany and France from 1901 to 1911. As one of a throng of expatriates, she gained a certain reputation in the Salons of Paris, creating traditional works for display. Though well painted, these were a notch below the skillful canvases of her Victoria contemporary Sophie Pemberton.

Hamilton returned to Canada to be with her dying mother in 1911. Then, through diligent effort, she parlayed her talent into something like a profession, using social connections to help her advancement. Hamilton’s childhood friend, Aurelia Widmeyer, married Robert Rogers who became a prominent politician and effected useful introductions. At a show in Ottawa in 1911 Hamilton sold three paintings to Canada’s Governor General, the Duke of Connaught, and his wife. Subsequently the artist spent “a day in the studio” with their daughter, Patricia. From that point, Hamilton’s paintings were exhibited across Canada “under the patronage of the Duke and Duchess of Connaught.”

When the First World War broke out, the artist was living in Victoria and keen to return to Paris. But throughout the war years women were denied the chance to go to France. So she prepared and planned, establishing connections with The Amputees Club of Vancouver. She put her art at their service for fund-raising during the war, and invented a project to paint the battlefields as a memorial to the dead and injured Canadians.

Hamilton’s first painting of a war theme is The Return Home (1919) showing the troop ship The Empress of Asia coming into Vancouver harbour. Irene Gammel, in her biography of Hamilton, I Can Only Paint, describes it:

This debut war painting featured the prow cutting through the water in the early morning haze, the soldiers leaning over the bulwarks waving their arms, the flags of red and blue flying from the masthead. With the Rocky Mountains indistinct in the foggy background, recalling the style of the “tinted steam” paintings of J.M.W. Turner and Claude Monet…. (p. 63).

Aside from a shared haziness, to compare her art with that of Turner or Monet seems a bit of a stretch. (Also, the mountains of Vancouver’s harbour are not the Rockies).

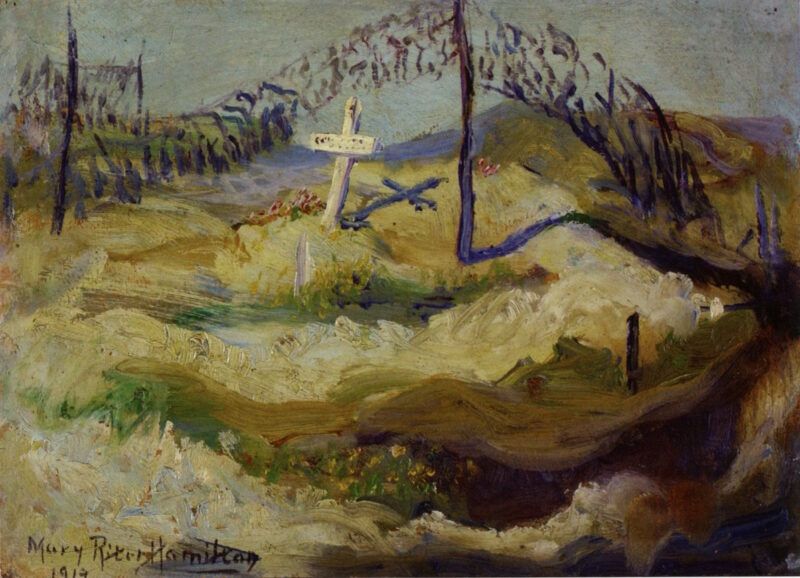

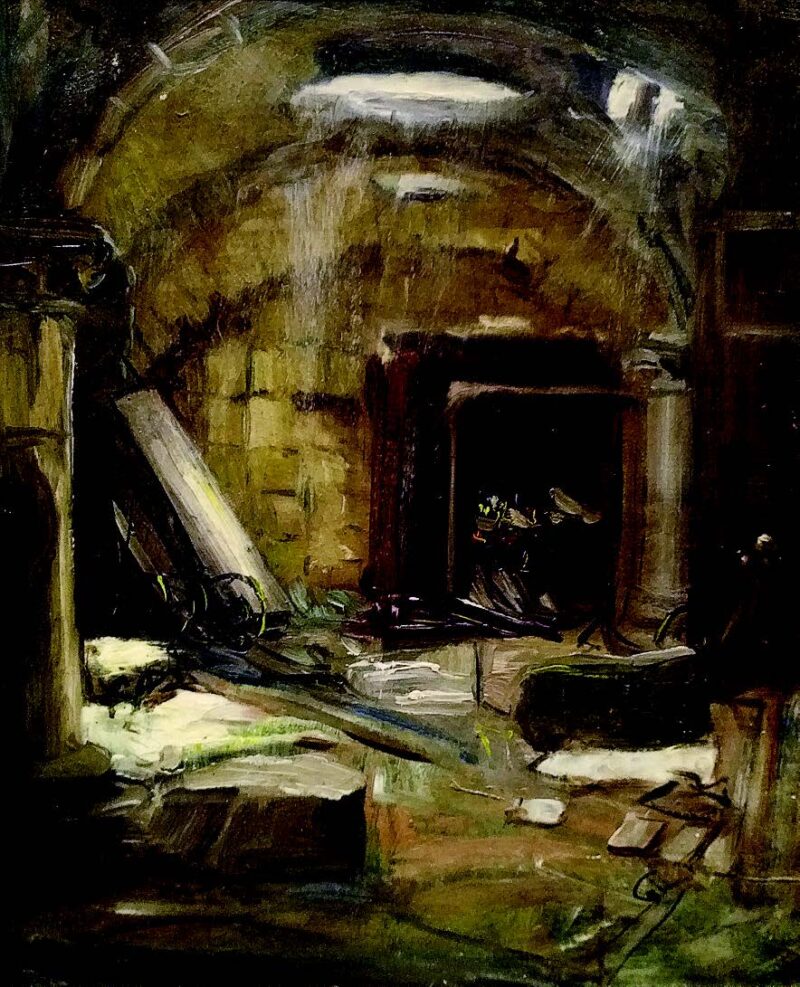

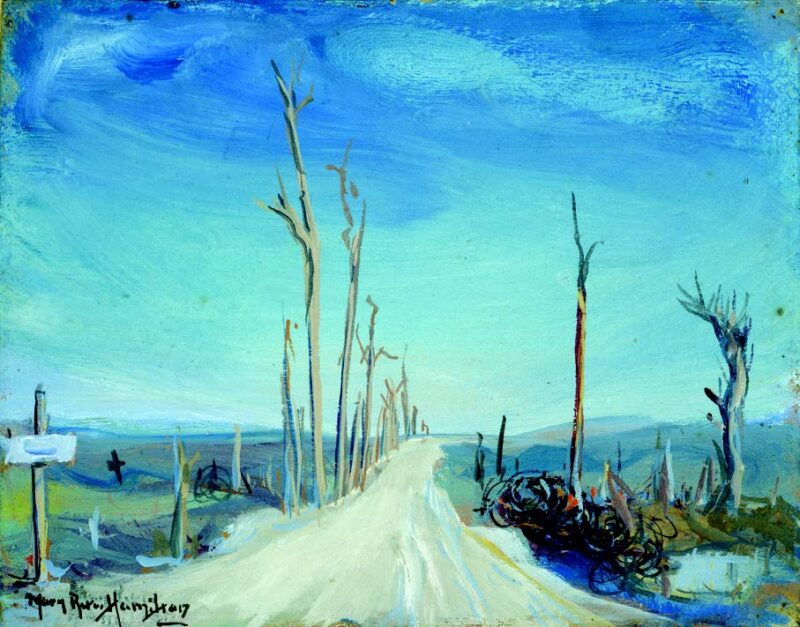

When hostilities ceased in Europe, the artist sailed to the unregenerate ruins of northern France as soon as possible. She was promised support by the Amputation Club of British Columbia and planned to work on a commission from its Gold Stripe magazine. Hamilton arrived in France on April 13, 1919 and was given shelter in disused army shelters. Later she camped among the ruins, working diligently in the field until November 1921. Gammel tells an engaging story of the artist going hungry, hiking miles and sharing dugouts and destroyed buildings with “corpse rats.”

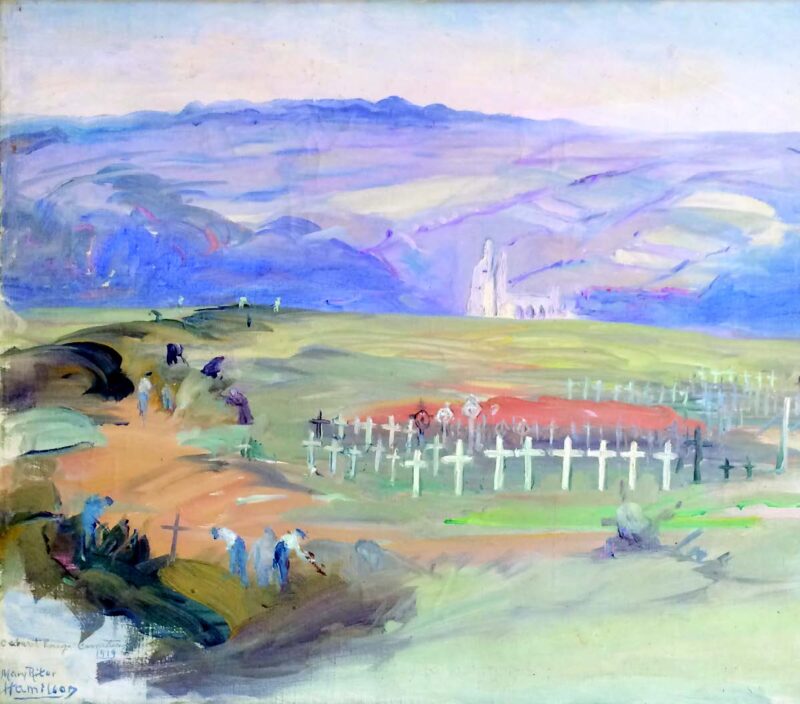

It was not only unsavoury work, but dangerous too. “During the war, an estimated one billion shells were fired, and as many as a third of them failed to detonate. These unexploded shells, many filled with mustard gas or other toxic chemicals such as phosgene or white phosphorous, had yet to be collected and defused” (p. 82). Among Hamilton’s companions were Chinese labourers clearing the terrain of unexploded bombs and casualties: “Each work is imprinted with her labour,” Gammel notes. “In this way, her work is akin to that of the war grave workers who struggled through the same sites of destruction, searching for the bodies in the swamps and returning deeply affected by the experience” (p. 212).

Many of Hamilton’s paintings depict shell craters, ruined buildings and graveyards, and inevitably the images are filled with sadness. Gammel writes “For Hamilton, who insists on being near the sites she witnesses, the cemeteries are extensions of a lost humanity seeking a connection through emotional immersion, and her role is to forge a relationship between the dead and the living through her art” (p. 269). And Gammel continues:

Her embodied approach connects her directly with the landscape of war, the result of her hand guiding the brush but also the work of her feet (as she trekked the Somme) and her entire body (as she sometimes slept there and often went hungry). Each work is imprinted with her labour. In this way, her work is akin to that of the war grave workers who struggled through the same sites of destruction, searching for bodies in the swamps and returning deeply affected by the experience (p. 212).

Before, during and after the war, Hamilton received no support from government or institutional sources. She was shut out of Lord Beaverbrook’s Canadian War Memorials Fund, was rebuffed by his Toronto adviser Sir Emund Walker and was discouraged by Eric Brown, Director of Canada’s National Gallery. In her book, Gammel makes political points about society’s neglect of Hamilton and, to drive them home, she compares Hamilton to official Canadian war artist David Milne who was on the battlefields at the same time: “With his generous allowance for painting supplies, sizeable salary, and military rank, in addition to a Cadillac and driver, he was exempt from the material hardships she experienced. This stark contrast highlights the power that came with being a government-commissioned war artist” (p. 96).

After two years the battlefields had largely been cleared, and in late 1921 Hamilton relocated to Paris. She was in deteriorating mental and physical health yet, even so, during the next few years she exhibited her paintings with considerable success in Picardy and Versailles. She was awarded Les Palmes Académiques by the French government after her exhibition in the foyer of the Theatre National de l’Opera. Yet despite her persistent efforts the collection of battlefield paintings was never exhibited in England. Finally, with the support of Canadian friends, she was able to raise the funds to return with her paintings to Canada in December 1925.

During her time in Europe or in Canada the impoverished artist could easily have sold a few of the pictures to support herself, but she insisted on keeping the series together, to be used to assist the Canadian amputees. On her return she put on thematic shows in Montreal and Winnipeg, but found herself trying to memorialize the bitter results of a war which people were trying to forget. What little notice she received didn’t make much effect in the “roaring twenties.” In the summer of 1926, she donated 226 of her battlefield art works to the Public Archives of Canada, where they remain to this day.

Subsequently, the fifty-nine year old artist followed a chequered path, exhibiting, teaching and lecturing where she could. Increasingly her physical and mental problems necessitated stays in hospitals, including some years spent at Essondale Provincial Mental Hospital. The stress of the years she spent camping out in the battlefields had taken a toll. She died at Essondale, psychologically shattered and in poverty, in 1954.

*

In 1977 I was working at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. One day the registrar asked if I had seen an oil painting titled L’Etoile by Hamilton. The painting was listed in the accession books but it couldn’t be found. In the Dictionary of Canadian Artists I discovered a few basic facts about Hamilton, and began my research. The life of Mary Riter Hamilton was my first attempt to discover “the unknown artist.”

I made contact with descendants of Hamilton’s friends in Victoria, and was able to meet one of her elderly associates associates in Vancouver. I went to see her paintings at the Library and Archives of Canada in 1978, and I confess that what I found was less than overwhelming. The oils that she created on the battlefields at Ypres, Arras, Cambrai and Flanders appeared small, dim and dirty. Of course, in the post-war years art supplies were difficult to come by, Hamilton’s funds were meagre and apparently she ground her own colours. Later I hung a show of thirty-five of her works in Victoria, published a brief catalogue and essay, and then moved on. By the way, that painting titled L’Etoile eventually turned up at the gallery, a tiny undated oil on panel showing Place d’Etoile in Paris.

In following years others took up the cause of this artist, but about ten years ago, when Irene Gammel took up the task, at last Mary Riter Hamilton had found her true champion.

Gammel, a teacher of communications and culture, directs the Modern Literature and Culture Research Centre at Ryerson University in Toronto. She is well positioned to consider the messages and meanings of Hamilton’s art. In her lengthy book she discusses gender politics, elitism in the arts, memory and commemoration relative to warfare, post-traumatic stress and much more. She brings to bear the concepts of Ruinophilia, Affect Theory, Battlefield Tourism and Archive Fever. She quotes T. S. Eliot, Walt Whitman, Virginia Woolf, W. B. Yeats and John Masefield. She looks at Hamilton through the lens of Jacques Derrida, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Michel Foucault. This is perhaps the only book about a Canadian artist which makes reference to José Medina’s study, “Toward a Foucaultian Epistemology of Resistance: Counter-Memory, Epistemic Friction, and Guerrilla Pluralism,” in Foucault Studies (September 2011).

Gammel unearthed an extraordinary amount of information in researching Hamilton’s life and the hasty little paintings she left behind. I pored over every word, as Gammel filled in the empty spaces I had left throughout my brief biographical essay forty years before. Peering into community records and newly-discovered caches of family letters she discovered many new details. Gammel dug into the embarkation records of Transatlantic ocean liners, the Nominal Roll of the Canadian War Graves Detachment, and The History of the Counties of Teeswater and Culross. The depth of her research can be seen in the almost one hundred pages of chronology, notes, bibliography and index at the back of her book. [That said, I was disappointed that she did not mention the works by Hamilton in the collection of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.]

Despite Gammel’s diligent and excellent work, my opinion of Mary Riter Hamilton as an artist hasn’t changed much. She was not very successful, and her later paintings were not often beautiful. Perhaps they were not intended to be. But it appears the paintings have been cleaned since I saw them last and I now see more than I saw before. The careful selection of full-page or two-page spreads show the artist at her most attractive, represented by excellent photographs and modern high-resolution printing in this profusely illustrated volume.

This is not a book for just anyone. It’s a book about the wreckage of war and the often sad facts of the life of an essentially unknown artist. While one cannot expect much joy from such a theme, there are bursts of hope. “Hamilton was no doubt conflicted herself about striking the right balance between memorializing the dead and moving on with life,” Gammel explains (p. 179).

In her book, Gammel too is at pains to strike the right balance. As I read this long and detailed volume, somehow Irene Gammel shows me why I should pay attention to this essentially unknown artist. She has retrieved a timely and thought-provoking story from the scattered fragments of a life, and presented it in a finely produced volume. In Gammel, Mary Riter Hamilton has found her ultimate biographer.

*

Robert Amos was the art writer for the Victoria Times Colonist newspaper for 32 years. His most recent books are the best-selling The E.J. Hughes Book of Boats, reviewed here by Brian Harvey; E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island (Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2018), reviewed here by Phyllis Reeve, and here by Alan Twigg; and E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia (TouchWood, 2019), reviewed by Phyllis Reeve. Editor’s note: Robert Amos has also reviewed books by Kiriko Watanabe, Kathryn Bridge, Robin Laurence, and Michael Polay, Keith McKellar, Sean Nosek and Ken Foster, and Scott Watson and Ian Wallace for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1115 An artist in the wreckage of war”

My great aunt on my mother’s side had a couple of early watercolours…

Great Artist…she gave so much for her art.