1096 A master of urban politics

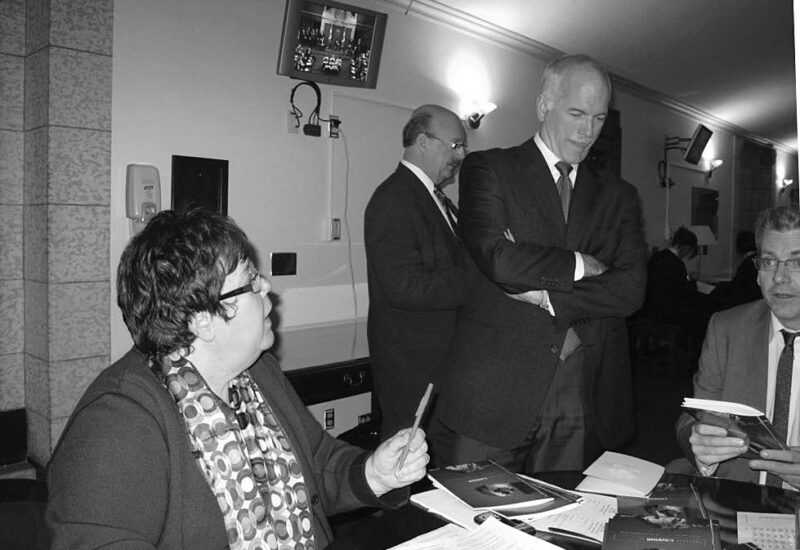

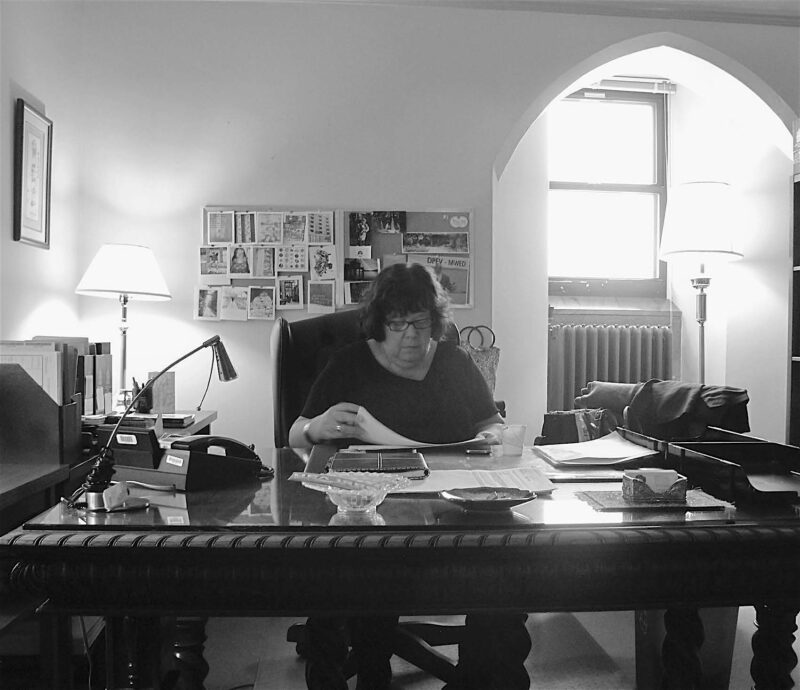

Outside In: A Political Memoir

by Libby Davies

Toronto: Between The Lines, 2019

$26.95 / 9781771134453

Reviewed by Alex Netherton

*

Libby Davies’ Outside In is an extraordinary political memoir that chronicles and reflects upon her life and political career first as an urban activist and then eventually as the Deputy Leader of the NDP under both Jack Layton and Thomas Mulcair. Libby Davies left politics just before the 2015 election that dashed the dream of social democrats taking federal power for the immediate future. Outside In has a lot to say about social democracy. It reveals a person who knows politics, and importantly does not hide her personal self from the politics she practices. They are closely related.

Libby Davies’ Outside In is an extraordinary political memoir that chronicles and reflects upon her life and political career first as an urban activist and then eventually as the Deputy Leader of the NDP under both Jack Layton and Thomas Mulcair. Libby Davies left politics just before the 2015 election that dashed the dream of social democrats taking federal power for the immediate future. Outside In has a lot to say about social democracy. It reveals a person who knows politics, and importantly does not hide her personal self from the politics she practices. They are closely related.

Much of Libby Davies’ political life centres in what we now call the “Downtown Eastside” of Vancouver, once known as “skid row.” For most, this is the neighbourhood where “there be dragons” — a place to be avoided, for it is home to marginalized urban populations: sex workers, those with mental health issues, those who are dealing with addictions, the impoverished, the homeless.

What brought Libby Davies to the Downtown Eastside? Her memoir clearly tells us it was her family. The passion for social activism and the pursuit of justice, the acceptance of being outside and a critic or power, and a love of politics were integral to Libby’s family. A UK service brat and daughter of an activist father, Peter Davies, and a progressive mother, Margaret Davies, Libby and her two sisters did tours of Malaysia, the Mediterranean, and of course, the UK, as the family followed Peter’s military tour around the world.

We see a young Libby mesmerized by adventures with a father whose wider mission in life had little to do with the military. (Libby and her father would later work together in the Peace Movement.) No less the outsider, Margaret Davies also faced real danger without drama, and always, Libby states, was impeccably dressed. Margaret was less rambunctiously impulsive than her partner, and Libby states that it was her mother’s concern for the consequences that would help shape the political skills she developed as an MP. (In later years some of you may have listened to Margaret performing as one of Victoria’s “Raging Grannies.”)

Emigrating from the UK first to Northern Alberta in 1968, when she was 15, and moving a year later to Vancouver, Libby literally followed her father’s footsteps as he began work as a social activist in the Downtown East Side. And yet this was not an automatic process. Libby found the world of activism much more compelling than finishing her BA. But the most important insight here is not that the Davies family had a calling, but rather that they were able to see the worth and potential of the community. Most of us would be blinded by the dragons.

Libby had a mentor — the extraordinarily gifted and legendary Bruce Eriksen (1928-1997), a brilliant, passionate, and self-educated activist with allies centred around the newly-formed Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA) and progressive urban politicians. Together they had entered a prolonged political campaign in what Jane Jacobs would have termed a conflict between developers and neighbourhoods. But it was more complex. One gleans that Eriksen’s objective was to ensure that commercial and government authorities begin to respect and uphold the rights and essentially the dignity of the residents of this community. In doing so these activists changed the name of the community from a “skid row,” a sort of death row label for a community without intrinsic value, to what we know today as the Downtown Eastside.

A second objective was to stop the mindless bulldozing of poor urban areas so common in that period. So, while Toronto may have had its “Stop Spadina” moment, Vancouver had its “stop the bulldozing of the Carnegie Library” moment. In this struggle, Carnegie Library escaped the wrecker’s ball only to be repurposed into a major community centre. And this was the pattern that followed: heritage architectural landmarks were repurposed into institutions formed to serve the Downtown Eastside community. New institutions emerged to invest in social housing and community services. Even UBC and SFU moved satellite campuses close to the Downtown East Side. BC governments of all stripes began to invest in social housing.

But this was not a political campaign with an ending. The area still faces a human condition not shared by other parts of the city. Dragons remain. But this experience solidified Davies’ conviction that progressive politics was about working with community-based activists and organizations towards shared objectives. Bruce Eriksen provided the extraordinary model. And Davies’ memoirs are constantly sprinkled with the poetic and artistic reminiscences of the people she worked with.

During Libby Davies’ urban political career, her personal life was intimately related to her public career. She and Bruce lived together, served on City Council, and had a son, Lief. Libby’s account of these years tells the reader that they literally had nothing and everything. But such ideal states do not last. The coterie of progressives on City Council began to move on. Bruce retired, and Libby, the urban crusader, made an unsuccessful run for mayor in what she admits was a poorly orchestrated campaign. And finally, Bruce succumbed to a cancer in 1997.

In what appears to be a characteristic response to emotional crises, Libby, with Bruce’s blessing, started a prolonged campaign to capture the NDP nomination for Vancouver East and then successfully campaigned to represent the area. At this point her memoir changes in tone. What emerges is less a biography of the good fight than a reflection on the NDP as a political party. Initially dismissed by the powers to be as a naïve urban crusader, Libby developed the political skills to be the federal NDP’s House Leader and then Deputy Leader under both Jack Layton and Tom Mulcair.

For those not familiar with political parties, social democratic parties like the NDP stand out for their commitment to internal democracy. At core is the idea that party policies and eventually platforms come from the party membership, not from one faction, the “parliamentary” group, or the party leader. As a result, annual conventions are the forum in which constituency representatives come together to stitch together party policy and platforms. These internal processes provide for interesting politics around what resolutions would constitute policy and platforms, a process in which the party leadership has important advantages.

A second key relationship is with organized labour. One of the conundrums of the NDP from its inception has been that despite is structural ties to organized labour, the majority of working people did not vote for the party. Libby Davies came to political age during the time when organized labour’s structural financial and political ties to the national party declined, in part because of the political changes associated with neoliberalism, in part because of the growth of newer political movements and identities outside of organized labour. Indeed, the NDP, like all social democratic parties, must knit together party policies and commitments that will unite a diverse set of progressive political forces. Stated another way, social democratic parties had to come to grips with the realization that “policies make politics.” If the older postwar model of social democracy was not viable, the party would have to develop policies to attract the newer political constituencies that were emerging at that time.

Libby Davies came to Ottawa in 1997, when NDP Leader Alexa McDonough had brought the party to the centre under the then popular “third way,” or post (traditional) social democratic politics. While there had been some success in this movement among NDP parties at a provincial level, similar gains evaded the party at the federal level. It is from this perspective that Davies’ memories are quite pointed. When Davies arrived in Ottawa, the party had alienated its traditional base when pursuing more centrist policies. But it turned back to rekindle its left wing and develop its new progressive base at the millennium. Here the arduous party building work of Jack Layton would eventually bring the party to the point where it could see itself forming a national government.

Both Davies and Layton had entered federal politics from urban political settings at a time when the NDP’s urban and national agendas shared key elements: mobilization against nuclear arms escalation and in urban spaces, campaigns against violence against women, the protection of sex workers, the cultivation of harm reduction strategies in urban settings, such as the much contested Vancouver Incite needle exchange, and of course, the continued pressure of homelessness and affordability issues. For much of Davies’ federal political career, the party fought to achieve its priorities in the context of federal Liberal and then Harper minority and majority governments. That was her second good fight.

Davies chronicles a transformation of the NDP. She came to Ottawa when the caucus was a decentralized cadre in which each pursued their own, as opposed to a collective agenda. But with the arrival of Jack Layton and the sense of growth as a national party, and the hope of attaining power, the leader transformed the caucus into a more cohesive, coordinated, and disciplined whole. According to Davies, Layton was able to do this because of a style of considered leadership and an ability to link with the party’s base. While the memoirs celebrate Jack Layton, the treatment of Davies’ relationship with Tom Mulcair and party leadership is gently more nuanced. In fact there were major differences and no little tension between the two.

First, Libby had continued in the footsteps of her father to be active in the peace movement. But part of those activities also brought her to criticize Israeli treatment of Palestinians, and one such instance saw her branded as anti-Semitic in the national press, by Liberal cabinet ministers, and more importantly by Mulcair. Davies goes at length to illustrate the process — an extraordinary demonstration of the politically charged relationship between criticism of the state of Israel and allegations of anti-Semitism in Canadian politics. The left-progressive support of the Palestinian cause has become embroiled within the existential conflict between the two sides. In this equation, criticism of Israel, particularly what is considered unbalanced criticism, or criticism that questions the legitimacy of the state of Israel, is equated to a new form of antisemitism. Libby Davies, the peace activist MP, almost terminated her career because of one important but badly phrased answer to a question from a hostile journalist. And yet, there is no little truth to the sentiment that the peace created by the gun is not peace at all, and that there needs to be a just settlement between two vastly unequal parties.

Davies left politics before the 2015 election that brought the Justin Trudeau Liberals to power. This was also the election that destroyed the NDP dream of taking power, a dream that had been nourished for the four previous years when the party had a breakthrough in Quebec and became the official opposition. For Davies, the party under Mulcair remained cohesive, but at the same time decision-making became too concentrated within the hand of the party leader. Mulcair did not have the Layton touch for broad consultation and including diverse elements of the party in his decisions. One could conclude that the party had lost touch with its base. It had become too ideologically conservative or cautious after years of battling the Harper Conservatives and did not adapt to new realities. And this is a credible argument.

Davies, however, offers a different explanation. In her view, politics is not about ideologies, but about working with allies to get things done. This had been her modus vivendi in urban politics and also what she learned from Jack Layton in Ottawa. In Outside In, Davies highlights her experience in getting support from all diverse quarters to move on pressing issues. In this sense the role of a parliamentarian centres on aiding and supporting progressive organizations, not in advancing a media-driven ideological struggle. Indeed, one of Libby Davies’ strengths is that she understood the relationship between community groups, social movements, and the party. The former are dependent upon the latter to make political gains, and the latter need support of the former to widen and deepen its political base.

And yet it is clear that numbers really matter. The NDP found an opening when Jack Layton, who always wanted to advance practical benefits, pushed the Harper Conservatives for concrete concessions on social and environmental policy. Layton’s notion of using leverage during a minority government is a lesson evidently not lost on Jagmeet Singh, who has put an NDP stamp on the minority Trudeau government’s response to the pandemic.

Davies’ title, Outside In, also reveals a long personal and political travail. She links her evolving view of politics with her coming out and union with a second partner, Kim Elliott. Part of this was to highlight how things have changed. Her decision to live and have a child with Bruce Eriksen became a scandal story — believe it or not — in the mean-spirited mores of 1980s Vancouver. But Libby’s revelation of love and partnership with a woman was both a “coming out” and a testament to the fact that human sexuality and identity are complex and changing.

It also comes hand in hand with Davies’ gender analysis of media and politics. She had been working on women’s issues from her first engagement in urban politics. Yet this memoir presents a critical reading of contemporary party and parliamentary politics as a highly-gendered male sport. In her chapter on inter-party collaboration, Davies presents the case that significant opportunities are lost because male ego and pride prevent collaboration and compromise. And perhaps this is the point where others have also pointed to the necessity of doing things differently.

And yes, there is certainly room for change. And here is the point: those who are now on the outside may just be ahead of their times. The dreams of a better life, for the creation of safe, secure and equitable urban spaces, for a better way of doing things are the stuff not only of dreamers, but of activists and politicians with their feet on the ground. Canada’s urban space is ripe with homelessness, with an affordability crisis, an environmental crisis, and an economic system that offers too much precarious labour for those seeking to make a decent living. Temporary pandemic neoliberal financial support does not change this predicament. More people are dying from the Opiate crisis than COVID-19. Outside In: A Political Memoir is a worthwhile read. Where are the Libby Davies of our generation? They are certainly needed.

*

Alex Netherton is a professor in the Political Studies Department at Vancouver Island University, where he teaches Canadian and comparative politics. President of the BC Political Studies Association, he is also the managing editor and co-editor of the Canadian Political Science Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1096 A master of urban politics”