1095 Iniquity on the Gulf Islands

As if They Were the Enemy: The Dispossession of Japanese Canadians on Saltspring Island

by Brian Smallshaw

Victoria: University of Victoria, 2020

$24.95 / 9781550586671 (available at UVic bookstore for $24.95 plus shipping costs, or direct from b@pixelmap.ca for $26.00 including postage)

Reviewed by Marie Elliott

*

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, the Canadian federal government enacted Order in Council P.C. 365 under the War Measures Act, creating a “protected area” of 100 miles inland along the BC coast “from which enemy aliens could be removed.” Although Japanese Canadians had lived and worked in British Columbia since the 1880s and were never enemies, the Order forbade them to fish or use vessels off the coast. To make certain the order was followed, the Royal Canadian Navy impounded all their fishing boats. The Mayne Island boats were towed to the Fraser River in mid-December. On April 21, 1942, 611 Japanese Canadian men, women and children were evacuated from the Gulf Islands and delivered by Canadian Pacific Railway ships to the Hasting Park Detention Centre at Vancouver.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, the Canadian federal government enacted Order in Council P.C. 365 under the War Measures Act, creating a “protected area” of 100 miles inland along the BC coast “from which enemy aliens could be removed.” Although Japanese Canadians had lived and worked in British Columbia since the 1880s and were never enemies, the Order forbade them to fish or use vessels off the coast. To make certain the order was followed, the Royal Canadian Navy impounded all their fishing boats. The Mayne Island boats were towed to the Fraser River in mid-December. On April 21, 1942, 611 Japanese Canadian men, women and children were evacuated from the Gulf Islands and delivered by Canadian Pacific Railway ships to the Hasting Park Detention Centre at Vancouver.

When April arrives in all its spring glory, cherry trees burst into blossom in many Vancouver Island communities. Some of the trees were planted in memory of the departed Japanese. With As if They Were the Enemy: The Dispossession of Japanese Canadians on Saltspring Island, Brian Smallshaw has provided an in-depth legal and practical account of the Salt Spring’s Japanese Canadians, who were an important part of the much larger Gulf Island and Vancouver Island communities affected by OIC P.C. 365.

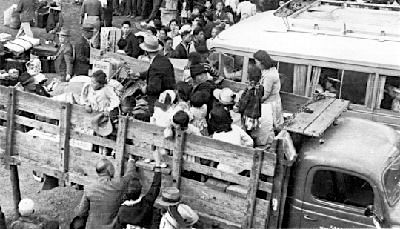

Acting on orders from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, on April 21 the CPR ship Princess Adelaide collected 486 evacuees from Chemainus at 7:00 a.m., and the Princess Mary took on 125 more people from Salt Spring, Mayne, and Galiano Islands by 3:30 p.m. According to RCMP instructions, everyone had to be delivered to the Hastings Park Detention Centre at Vancouver by 7:30 p.m. “to avoid confusion.”[1] When local residents on Mayne Island went down to the wharf to wish their Japanese neighbours farewell, one woman brought forget-me-nots to pin on their lapels.

Etsuji Teramoto was not one of them. Just before midnight on December 7, 1941, he had been taken away to Salt Spring on the Provincial Police boat with Mineichi Minamide and three other “enemy aliens:” his brother Shoji Teramoto, uncle Kumajiro Konishi, and Shintaro Sasaki. Car keys were seized for 24 hours to prevent their families from following them.

Left without transportation, Esuji’s wife, Tsune, and their children took care of closing down their home. On evacuation day they were joined by Mrs. Konishi and four cousins. The two mothers and their children walked two miles to the Miners Bay wharf carrying their suitcases. They had carefully chosen what they would take because only 150 pounds per adult and 75 pounds per child were allowed. Remaining items had been packed and strategically stored away with friends who volunteered to care for them. At Christmas time Minamide friends were notified where their presents of Saki were buried. With the families gone, the one-room school was closed for the next two years.

Little preparation time was allowed for residents who had a thriving businesses on the coast, such as the Royston Lumber Company at Courtenay and the twelve Mayne Island families involved with the Active Pass Growers Association. The growers had just planted their enormous greenhouses for the season: in 1941 Kumazo Nagata had shipped over 100 tons of tomatoes. Kumazo’s son, Ken Nagata at Port Alberni, optimistically started 5,000 plants in his new greenhouse in February 1942, but he could not find a caretaker before he was removed thousands of miles away to an Ontario road camp. His loss was 30,000 pounds of tomatoes. Kumazo managed to find two caretakers for his own greenhouses on Mayne Island. The houses amounted to an acre under glass and were heated by a new technology of hot water circulatory heating.

On April 15, 1942, Kumazo put in a plea to the BC Securities Commission, on behalf of the non-Japanese local workers who had helped with the tomato industry over the years:

At this time may we convey to you our opinion that those already in employment now be permitted to remain so, while possible for them, as we do not wish to have their source of income deprived from them while the greenhouses are being operated by our successors. These persons, though not Japanese, have been our assistants for many years.[2]

This generous – in the circumstances – proposal was accepted and 150,000 pounds of tomatoes were produced for wartime consumption, the greenhouse workers remained employed, and contracts with the CPR and Slade and Stewart wholesalers in Vancouver remained intact.

Since the RCMP were involved, there was little the residents could do to help their neighbours, but retired Lieut.-Col. Charles Flick tried his best. “He was very much our ‘friend in need,’” John Nagata recalled. “When curfew was enforced he personally carried the messages after daylight hours. When we couldn’t use our motor vehicles he found a way around the barrier. He stuck his neck out in many ways for the benefit of his Japanese neighbours on the island.”[3]

Flick accompanied Kumazo and John Nagata when they met with Col. E.C.P. Salt, Retired RCMP Officer in Command at Hastings Park. John recalled, “We were enlightened but since the Order in Council was passed we had to comply by it.”

Soon after families were reunited at the Hastings Park Detention Centre, important decisions had to be made on where they would find employment and a place to live. Mothers with young children desperately wanted to move away from the unsanitary horse stalls. They received help from Rev. Yoshio Ono, Cumberland Japanese Mission of the United Church, who pressed for better conditions.

Deep-seated family ties between Mayne Island Japanese Canadians helped them through very rough times. They traced their heritage back to Agarimichi, Tottori Prefecture, Japan. The Nagata family joined forces with their Konishi and Sumi relatives and about 15 other families, and found work on a farm at Turtle Valley near Salmon Arm. Hoping that they would soon be returning to the Gulf Islands, they built temporary housing out of green lumber and tarpaper.

But as the siding dried it created large cracks. Consequently, the families spent a miserable cold winter in sub-zero temperatures. What they thought would be a temporary period dragged on, and after two years they moved out. Some went to Kamloops, some to Toronto. The Nagatas stayed near Salmon Arm, while the Murakami and Minamide families chose to work on the vast sugar beet farms at Magrath, Alberta. Unfortunately, Boon Minamide sank into a depression and died. As John Nagata explained, “He was not used to an idle life; for about three months there was very little to do.”

After four years Etsuji Teramoto was discharged from the work camp and finally reunited with his family. He found work in the greenhouses at Brampton, Ontario, and established a popular market garden. Several years ago the Teramotos’ many years of involvement in the community were recognized by naming a large public park in Brampton their honour.[4]

*

In As If They Were the Enemy, Brian Smallshaw relates the story of two Salt Spring Island families, the Iwasakis and the Murakamis, who fought hard to return to their properties. He also examines how the Canadian government quickly introduced seven Orders in Council that prevented Japanese Canadians from doing so. Smallshaw makes a convincing case that these Orders in Council – included here as Appendices — should never have been imposed.

Kumazo Nagata’s son John was one of the Japanese Canadians who petitioned for a commission to investigate property losses. This led to Order in Council PC 1810, The Royal Commission to Investigate Complaints of Canadian Citizens of Japanese Origin, as well as the Bird Commission. John Nagata, who saved the cheque stub received from the Cooperative Committee Claim Fund, dated November 17, 1947, thought that the recovery price was about 30 to 40 percent of the actual value in 1942 or earlier.[5]

Torazo Iwasaki owned the largest piece of Japanese Canadian property on Salt Spring. He found it especially galling that the Custodian of Enemy property was allowed to purchase it. With amazing determination he took his case all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada … but lost. Smallshaw argues that the liquidation of Japanese Canadian property was a breach of trust under the War Measures Act and was illegally applied to Japanese Canadian citizens.

Rose Murakami (born 1937), a retired UBC professor of nursing, has ensured that her family’s story of property loss and reclamation survives in her book, Ganbaru: the Murakami Family of Salt Spring Island (Ganbaru translates as “toughing it out”). She has also donated material to the Salt Spring Archives, and assisted the Japanese Garden Society to establish a memorial garden. What is not well known is that her family generously provided land worth $1.2 million to build a low cost, 27 unit housing project for residents of Salt Spring Island. In 2018, Keiko Mary Kitagawa, Rose’s sister, received the Order of British Columbia for gaining the support of the University of British Columbia to grant honorary degrees to the surviving Japanese Canadian students of 1942 who had not been allowed to finish their degrees. This took place at UBC’s May 2012 graduation ceremony. Keiko also successfully campaigned to rename the Howard Green federal building in downtown Vancouver the Douglas Jung Building in honour of the first Asian Canadian to be elected a member of Parliament.

*

When Gavin Mouat of Salt Spring was named Custodian of Alien Property, my father, who was the caretaker for the Minamide greenhouses and farm, met with him occasionally. The Minamide farm was one of a number on Mayne Island being held for returning veterans. My family was also present on December 1, 1943, the day that Mouat auctioned off all the Minamide belongings from the back of a dump truck. Nearby was their partly finished new home that they had to abandon in 1942. Rural zoning by the Islands Trust has ensured that the beautiful farmland is still intact. The sturdy old barn and workshop have been restored by owners, and several large charcoal pits protected.

The Nagata home at Mayne Island, minus the attached glass starting-house, was rented to families for many years before it became a popular restaurant. In the 1960s John Nagata purchased waterfront property close to where his father’s greenhouses once stood and built a summer home for the family.

With enthusiastic co-operation from members of the Mayne Island Lions Club, a Japanese Memorial Garden was established at Dinner Bay on land the Adachi family had rented from the pioneer Dalton Deacon family. Prior to their removal, the Adachis had raised chickens and grown strawberries on the large field. Over time, with donations of cherry trees and other plants from Canadian Japanese nurserymen, and expert advice and labour from Tosh and Mitsi Saito, the garden has carefully evolved. For an educational feature, a charcoal pit was dismantled and removed to the garden entrance. A service shelter was built nearby for public use and named the Adachi Pavilion.

As if They Were the Enemy has sorted out why remembered events involving the Canadian Japanese residents occurred and how they could have been avoided. Brian Smallshaw’s book will become a valued reference for all British Columbia historians and legal experts.

*

Marie Elliott has a Master’s degree in history from the University of Victoria. She has written numerous articles and books about BC settlement history, including Mayne Island and the Outer Gulf Islands: A History (Gulf Islands Press, 1984) and Fort St. James and New Caledonia: Where British Columbia Began (Harbour: 2009). Her most recent book is Gold in British Columbia: Discovery to Confederation (Ronsdale Press, 2020). Editor’s note: Marie Elliott has also reviewed Interwoven Lives: Indigenous Mothers of Salish Coast Communities, by Candace Wellman, for The Ormsby Revieew.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] Midge Ayukawa collection, Nikkeii National Museum and Cultural Centre.

[2] Nagata to BC Securities Commission, April 15, 1942, RG 36/27, 9 file 208. Library and Archives Canada.

[3] My thanks to John Nagata and Mitsuko Shirley Teramoto who provided most of my information used here through correspondence.

[4] Information on many Japanese families who moved to Ontario can be found in Tracing Our Heritage to Tottori Ken Japan, compiled by the Ontario Tottori Ken Jin Kai Book Committee, Brampton, Ontario.

[5] Personal communication, John Nagata.

2 comments on “1095 Iniquity on the Gulf Islands”

You can follow the history of the Mayne Island families into the Interior of BC in the book Vanishing British Columbia (2005, UBC Press), and here.