1060 Watercolours & wooden churches

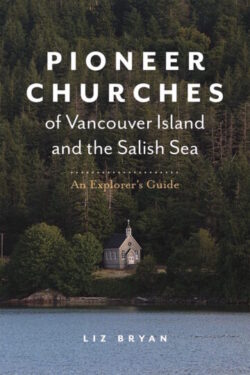

Pioneer Churches of Vancouver Island and the Salish Sea: An Explorer’s Guide

by Liz Bryan

Victoria: Heritage House, 2020

$24.95 / 9781772033052

*

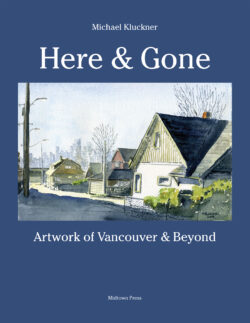

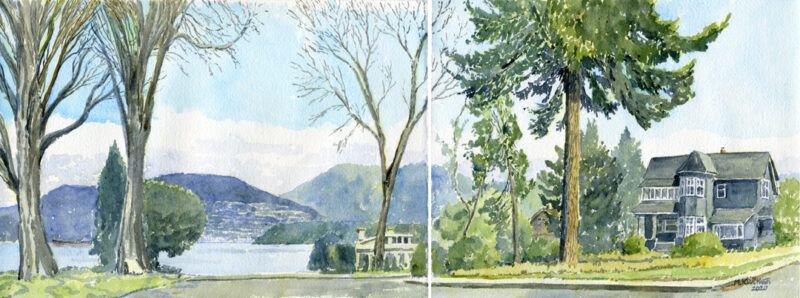

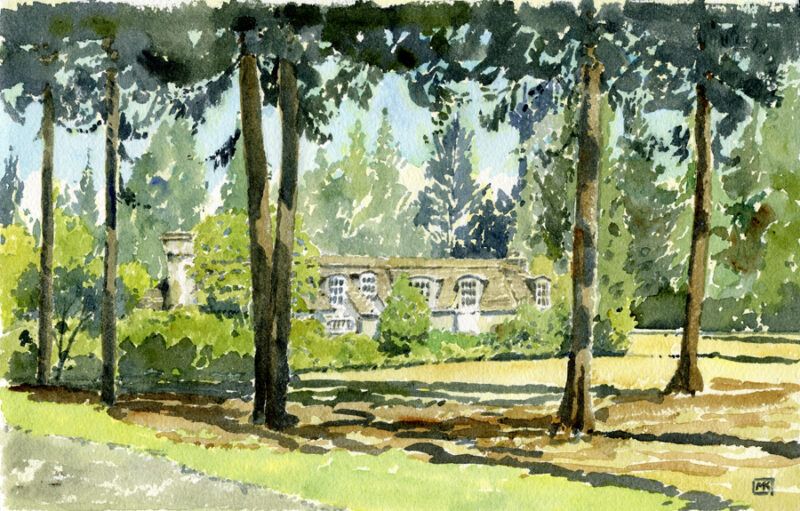

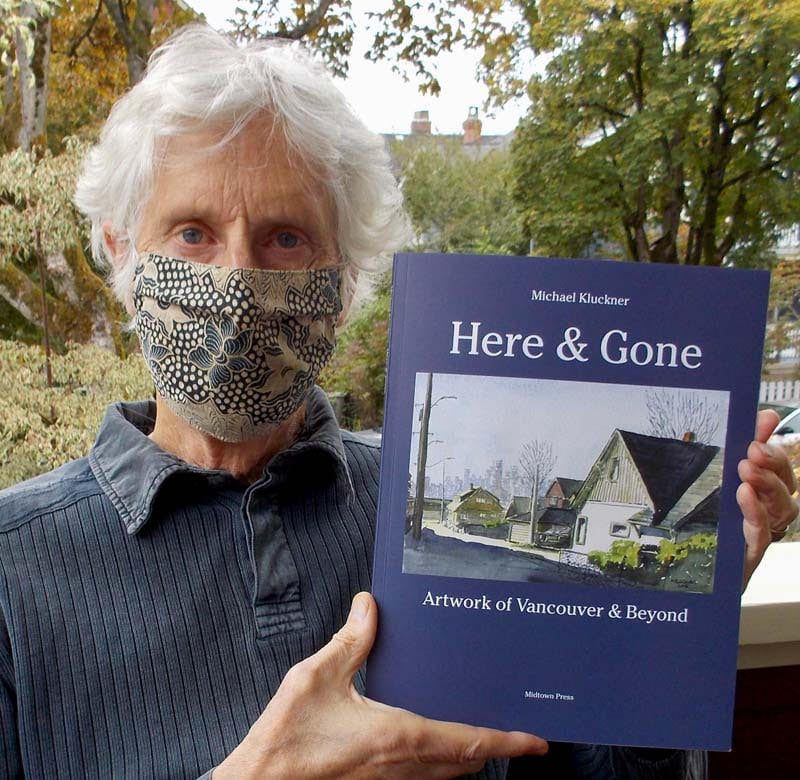

Here & Gone: Artwork of Vancouver & Beyond

by Michael Kluckner

Vancouver: Midtown Press, 2020

$19.95 / 9781988242385

Both books reviewed by Martin Segger

*

Gazing out from our COVID-induced shut-ins and lockdowns at the prospect of a grey winter stretching off into the cruel pandemic distance towards a hesitant spring, we could entertain few better distractions than an armchair read of a couple of architectural guidebooks. And indeed, Liz Bryan and Michael Kluckner give us two offerings so different from each other they could be read in serial alternation, almost like listening to two CDs on shuffle.

Gazing out from our COVID-induced shut-ins and lockdowns at the prospect of a grey winter stretching off into the cruel pandemic distance towards a hesitant spring, we could entertain few better distractions than an armchair read of a couple of architectural guidebooks. And indeed, Liz Bryan and Michael Kluckner give us two offerings so different from each other they could be read in serial alternation, almost like listening to two CDs on shuffle.

Liz Bryan’s pocketbook-sized Pioneer Churches of Vancouver Island and the Salish Sea would fit into your car glovebox for easy on-the-go reference, but just as well holds one’s attention for that armchair binge read. It is especially engaging if you have a mind’s-eye familiarity with the rural landscape and small towns of Vancouver Island since much of the subject matter is easily accessible on common driving routes. To encourage this (or assist the faltering mind’s eye) excellent maps are provided for each of five sections ordering the geographical arrangement of the entries. The building entries are treated as illustrated essays, headlined helpfully with name, build date, street address, reference website, and if you want to arrange entry or attend a service, a phone number. Liz Bryan is her own photographer and she provides good visual introductions to each site including overall exterior and interior views, context shots of adjacent graveyards, for instance, and highlights details such as stained-glass windows or furnishings.

Essentially a social history, Pioneer Churches is light on technical details or stylistic analysis that are so much the concern of mainline architectural history. Instead Bryan focuses on community context: Who built it? For whom? Why? How was it built? Who paid for it or donated the land? Quite often, answering these questions provides for an introduction to the social dynamics of these pioneering communities who were settling land, building towns, establishing businesses, and creating a cultural dimension to their lives through faith-based rituals and self-help organizations. What certainly comes through is how church building contributed to sustainability and resilience, quite often cutting across the stereotypical racial, national, or even religious divisions that we commonly associate with “pre-modern” times.

Often Byan reinforces this point through sketches of characters such as Swedish-born Rev. Ellison at St. Mary the Virgin, Metchosin (locally renowned for its churchyard spring carpet of native white fawn lilies). Oxford-educated Ellison achieved early notoriety by crossing the Alps on a penny-farthing bicycle. He served in India, then came to Vancouver Island as Royal Navy chaplain to St. Peter and St. Paul’s Church in Esquimalt. He combined his Metchosin posting with goat farming, but earned the ire of his Anglican bishop by burying a Roman Catholic priest in the graveyard, marrying a local European man to a Chinese bride, then “worst of all, for speaking out against the war in South Africa.” Thereupon he traded his religious calling for a homestead in Port Renfrew where he built a sawmill, later returning to Victoria to open a crematorium.

One can work through the Island’s ecclesiastical heritage chapter-by-chapter starting in the Victoria/Western communities, then the Saanich Peninsula, moving along to the Cowichan Valley, thence to Salt Spring Island (five churches), and finish with “Nanaimo and the North.” Altogether you visit some 45 buildings ranging from Victoria’s original 1858 Roman Catholic cathedral, which was moved and repurposed in 1890 as the St. Ann’s Convent chapel (and has since been meticulously restored as a National Historic Site); to St. Anne and St. Edmund Anglican Church (Parksville, 1892), a weathered gothic log structure, its rural woodland setting itself a study in the aesthetics of the Victorian picturesque.

Taking its cue from good guidebook user etiquette, the author thoughtfully supplies a very complete index, bibliography (presented as “suggestions for further reading”), a glossary of architectural terms, and locational image list. Liz Bryan, co-founder of Western Living magazine, and a well-published photographer and author, has produced a very professional, informative, and highly entertaining read — in or out of the armchair.

*

Michael Kluckner’s Here & Gone, a slimmer but larger format “art book,” is more suited to couch and fireplace. Most readers of The Ormsby Review will have at some point flipped through a Kluckner offering in a book shop, given or received one as a gift, or acquired a sampling of works by this talented and productive artist-author. Indeed, many of us will have tracked Michael’s career from self-admitted “hippie adventurer” through his various and often overlapping episodes as artist, farmer, historian, traveller, writer, graphic novelist, and Australian immigrant.

Michael Kluckner’s Here & Gone, a slimmer but larger format “art book,” is more suited to couch and fireplace. Most readers of The Ormsby Review will have at some point flipped through a Kluckner offering in a book shop, given or received one as a gift, or acquired a sampling of works by this talented and productive artist-author. Indeed, many of us will have tracked Michael’s career from self-admitted “hippie adventurer” through his various and often overlapping episodes as artist, farmer, historian, traveller, writer, graphic novelist, and Australian immigrant.

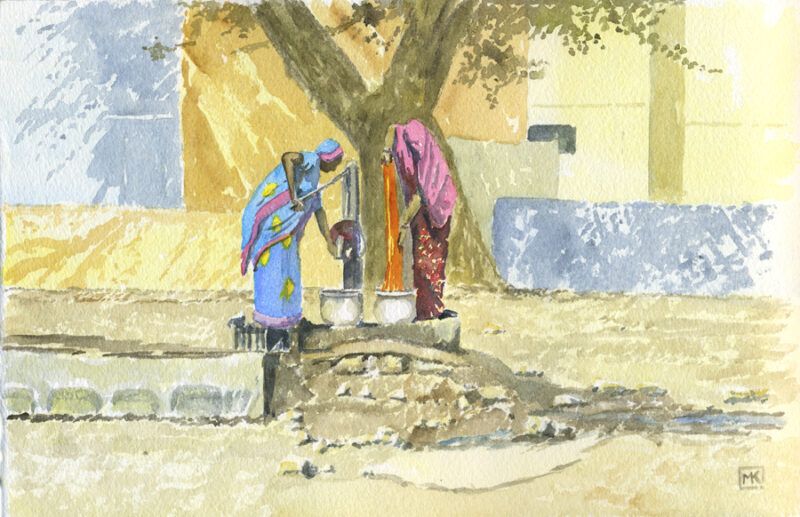

Here we find him in Covid lockdown rummaging through his studio attic to create a roughly thematic assemblage of images from his brush or pen that allow us to traipse with him around his beloved old Vancouver and then through a memory-bank of travels ranging from rural British Columbia to more exotic climes: Marrakech, Barcelona, Cornwall, Java, Rocamadour, Rajasthan, Yucatan, New South Wales. Even the mix of media seems serendipitous: here a quick plein-air water colour, there a pen-sketch, pencil-drawings from notebooks, and some particular treats: his distinctive Japanese brush-ink drawing complete with “MK” signature chop.

If there is a singular lens through which Kluckner has drawn these pieces it has to be nostalgia, for the “Here” always seems to be only perilously here, a weathered building, a shipwreck, a delicate landscape, even passers-by in a street seem to be just hanging on, or perhaps already almost a fading memory. The “Gone” lives mainly through the image commentaries, usually events that happened or people who were there — or sometimes personalities who were thought gone, but reappeared, like John Eek of the Eek Ranch in a picturesque valley near Rock Creek. Eek’s death was first reported by a correspondent on Kluckner’s website — and then corrected by another reader. Kluckner was pleased to discover that Eek was alive and well as a published cowboy poet (p. 40). An accomplished anecdotalist, Kluckner’s commentaries gently nudge the reader to sip some local history, or to taste the colours and characters flashing by a train window in some far-away foreign landscape.

*

Both these books share something of the long tradition of architectural travel guides. Victorian architects assembled reference files from notebooks that documented their European “study tours.” These formed an important part of their training and provided templates for their design careers. Some time ago your reviewer was able to examine a large collection of these notebooks housed in the archives of the Victorian and Albert Museum in London. The files include many of the great names in 19th Century architecture: Blomfield, Barry, Pugin, Lutyens, Smirke, Stuart & Revett. A few had worked their sketches up as popular guidebooks: for instance Sir Matthew Digby Wyatt, G.E. Street, and John Ruskin all drawing on their “Grand Tours” through Continental Europe. Others published their drawings as picture books: Thomas and William Danniell’s architectural views in Greece and India, and James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s detailed drawings of Greek classical ruins. Original editions are highly prized collectibles now.

The Architectural Archives of the Pacific Northwest housed in Special Collections at the University of Victoria contains similar records of architect study tours, including visits to Eastern Europe by modernist Shanghai practitioner Laszlo Hudec.

Also represented is Victoria architect John Di Castri, who trained at the University of Oregon under Bruce Goff — who was heavily influenced through a friendship with Frank Lloyd Wright. After graduating, Di Castri and his wife travelled across the United States photographing Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, on their way back dropping in to Wright’s Taliesin West studio to meet the great man himself. An extensive set of photographic slides documents the trip.

The richest UVic treasure trove of such material, however, can be found in papers of Richard Roskell Bayne (1836-1901). Part of his studies included two seasons of travels throughout Europe producing several volumes of notebooks with sketches and measured drawings. Bayne articled under the great British architect Charles Barry during the construction of the London Parliament Buildings before embarking on a career at Calcutta, India. Bayne competed for the design of the British Columbia Parliament Building. Losing out to Francis Mawson Rattenbury, he nevertheless retired to Victoria.

So Bryan and Kluckner participate in a rich tradition of research and writing, each adding a British Columbia take on a genre of publishing that contributes both personal and public narratives to the Province’s cultural landscape. Hopefully there will be more coming from them, both to tantalize the reader for the thrill of chase, or to provide more studied contemplation in an armchair on a winter’s night.

*

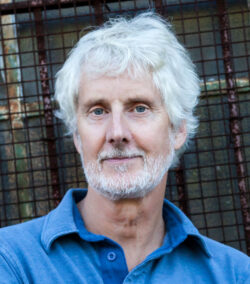

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of BC, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on BC historic and decorative arts. His most recent publication, concerning the Modernist architectural heritage of Victoria (1935 1975), Conservation Guidelines for Modernist Architecture in the Victoria Region (2020), is available in a free on-line digital version. Martin currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia and for Government House, Victoria. Editor’s note: Martin Segger has also reviewed books by Marc Treib, Daina Augaitis, Allan Collier, and Stephanie Rebick, Leslie Van Duzer, Richard Cavell, Sherry McKay, Robert Ratcliffe Taylor, and Darrin Morrison et al., among others, for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1060 Watercolours & wooden churches”