1055 Hodgson of the Arctic

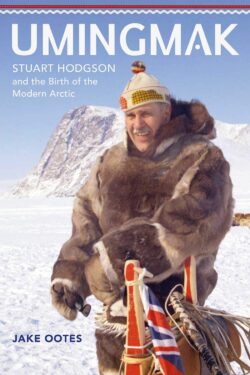

Umingmak: Stuart Hodgson and the Birth of the Modern Arctic

by Jake Ootes

New Westminster: Tidewater Press, 2020

$29.95 / 9781777010102

Reviewed by Dylan Burrows

*

“Going North” is an expression laden with expectation. Uninvited guests, Canadians trespass upon occupied Indigenous lands; they enact their desires on territory they imagine as uninhabited.

“Going North” is an expression laden with expectation. Uninvited guests, Canadians trespass upon occupied Indigenous lands; they enact their desires on territory they imagine as uninhabited.

In Umingmak: Stuart Hodgson and the Birth of the Modern Arctic, Jake Ootes stumbles northward to reckon with this colonizing aphorism, on both personal and national registers.

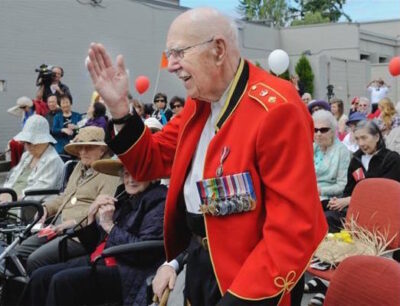

Outwardly, Umingmak is a tale of postwar nation-building in Canada’s “last frontier.” Ootes traces the career of Stuart Hodgson (1924-2015), a union leader and civil servant, during his tenure as Commissioner of the Northwest Territories from 1967-1977. Hodgson shouldered the task of bringing the institutions of self-government north.

Since 1870, the Council of the Northwest Territories (CNWT), an unelected body of bureaucrats, governed the region’s Indigenous and settler communities from afar in Ottawa. However, Ootes argues, the imminent arrival of multinational mining corporations in the late 1960s threatened to dispossess Indigenous peoples of lands and culture. To stem private capital’s inexorable advance, the federal government would “tutor” local people in the art self-governance.

Across five sections, Ootes chronicles Hodgson’s labours through personal recollection, oral interviews, and historical research. As Hodgson’s executive assistant and, later, a territorial MP and Minister of Education, Culture and Employment, he writes as an insider.

Perhaps this explains why Ootes neither confronts the colonial nature of territorial government, nor Hodgson’s ingrained paternalism towards Indigenous peoples. “The big challenge” of his mandate, Hodgson determines early on,

[W]ill be to educate local people about government. Hell, they’re hunters and trappers who don’t know anything about our ways. I’ve got to take power up there to them, or they’ll be trampled and assimilated, maybe even extinguished as unique cultures. Don’t ask me exactly how, but that’s what I’m going to do (p. 10).

He would launch a revolution from above, a neocolonial slight of hand: the bestowal of settler governance irrespective of existing Indigenous political and legal orders.

In Part 1, “A Leader in the Making, Ootes covers the CNWT’s 1967 relocation to Yellowknife, a town “on the edge of a huge wilderness filled with unknown peoples and cultures living in isolated communities” (p. 47). Indigenous residents appear unknowable, distant. They “hung around” the local bar, seemingly “lost and confused as Hodgson’s new arrivals” (p. 23). Ironically, Ootes writes Indigenous, presumably Dene peoples as loiterers within their own territories.

Indigeneity’s incommensurability with urban modernity is a tired but powerful trope — one the CNWT invokes to extend settler rule into Inuit and Dene communities. At the fist sitting of the territorial legislature, Councillor Lyle Trimble remarks that Inuit “have sixteen words for snow, but not one for government — they know nothing of it” (p. 59). For Trimble, Indigenous peoples were future “Northerners” in need of modernity’s civilizing uplift.

If Part 1 ends with colonial invective, Ootes opens Part 2 “Reaching All Northerners,” with an Indigenous refusal of its very logic.

In September 1968, Hodgson and Ootes drive to Behchokǫ̀ (Fort Rae), where local Tłı̨chǫ resist territorial plans to relocate their community. On the gravel road leading into town, they meet Chief Jimmy Bruneau, an elder and witness to the signing of Treaty 11 in 1921. “We’ve been here ten thousand years,” Chief Bruneau reminds his guests, “who are you?”

Dumbstruck, neither man replies, “unsure of our relevance to this community” (p. 65). Through an interpreter, the Tłı̨chǫ leader outlines Behchokǫ̀’s need for housing, clean water, and a new school, but rejects relocation outright.

After Bruneau ends their meeting, his interpreter lingers. “Your way is not our way. We signed peace treaties, not treaties giving our land away,” the young man reportedly says. “And now the federal government says Indians are to be the responsibility of the territorial government. The Chief doesn’t see it the way you do” (p. 68). This “wake-up call” prompts Hodgson to task Ootes with organizing a listening tour through the region’s communities that spanned March, 1969.

Chief Bruneau’s question, however, stalks their every move. The Tłı̨chǫ leader asked for more than their names. He demanded Hodgson place himself and the government he represented in relation to the land, its people, and traditional Indigenous political orders. Did they intend to be respectful guests? Or, were they colonizers — Indian Agents by another name?

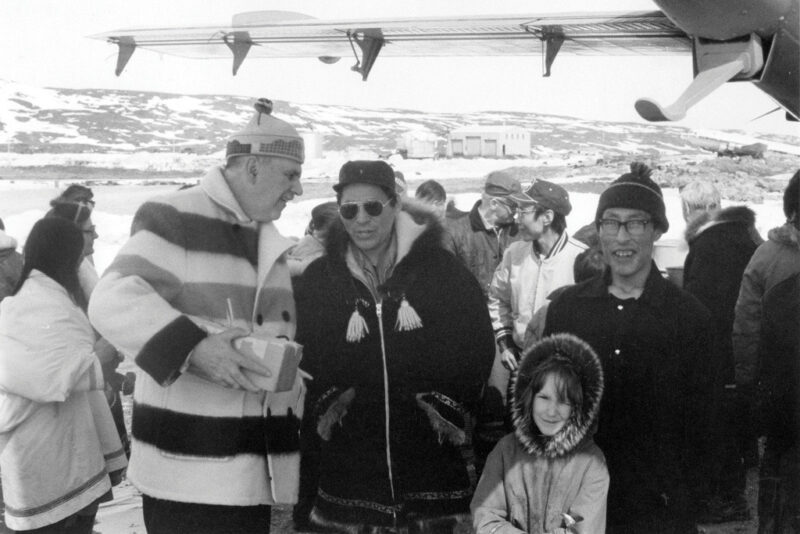

Ootes defers his answer, as Hodgson’s governmental party barnstorms the Arctic by plane. As a journalist, the author retreats behind his camera lens — an observer, not participant. From this safe remove, he remains unentangled and hence not responsible to the Indigenous communities he documents.

At times, Ootes indulges in ethnographic voyeurism. He reduces Indigenous people’s traditions of creative adaption to colonialism to snapshots of material poverty, notably at Sanikiluaq (the Belcher Islands), the final stop of their tour. “My camera recorded the hallmarks of community life in the Arctic: broken honey bags, frozen in place, and mounds of trash” (p. 136). He ends the scene on a literal uplift: Inuit and their guests cutting a runway through snowbanks for the government party’s plane. However, Ootes image of material desperation lingers, moulders.

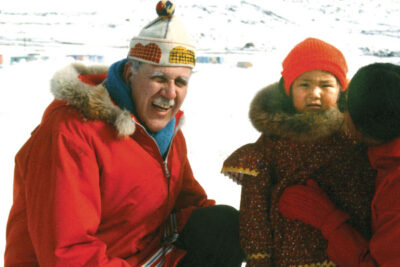

Elsewhere, he captures Hodgson’s earnest attempt to listen. In a community hall in Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay), Hodgson asks his Inuit audience to imagine the region’s communities as a herd of muskoxen. When threatened muskoxen form a defensive circle, horns pointed outwards to fend off predators. Under self-governance, Inuit would have the legal “horns” to hold rapacious resource corporations at bay.

This laboured analogy drew laughter and cries in Inuktitut of “Umingmak!” from the crowd. Seeing the commissioner’s puzzlement, his translator explained: “Muskox! Umingmak! Looks like you!” (p. 110). Hodgson’s large stature reminded his hosts of the Arctic’s most famous bovid. The name stuck even if talk of self-government was lost in translation.

“Umingmak,” more than a sobriquet, reads as an invitation. It is a diplomatic if humorous request for Hodgson to place himself in relation to the people of Ikpiarjuk, and transparently make his intentions known. Gathered under one roof, Inuit and the commissioner begin the awkward, unresolved dialogue about territorial governance.

In Part 3, “Emperor of the North,” Hodgson’s imagined community of unified, self-governing “Northerners” vanishes with the publication of the 1969 federal White Paper. The infamous report proposed to assimilate Indigenous peoples into the settler body politic. Repeal the Indian Act. Abrogate the treaties. Privatize reserve lands, among other measures, it argued, to set Indians on the path to modernity.

The Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories quickly formed to defend Dene sovereignty within Denendeh, their ancestral territory. James Wah-shee, later president of the organization, damned the White Paper for what it was: a framework for legislated genocide.

These existential stakes are lost on Ootes. Rather than engage with Indigenous critique, the author seeks out René Fumoleau, a widely respected Catholic missionary. “[D]on’t forget the Dene’s basic philosophy,” the priest says, “we’ve been here ten thousand years already, so we can easily wait out a few white intruders” (p. 267).

The Indigenous political resurgence that spills over Part 4 — aptly named “Turf Wars” — belies Fumoleau’s canned wisdom. In the 1971 election, a new cohort of Indigenous legislators rattled territorial council. “[W]e have to settle the question of Aboriginal rights and land rights,” James Rabesca, councillor for Behchokǫ̀ declared, “before we, the native people, can really be considered members of the Just Society” (p. 221).

Activism unbounded by legislative protocols, however, confounds Ootes, especially Indigenous women’s labours. At Wah-Shee’s invitation, the author guest-judged the 1971 Indian Princess Pageant at Behchokǫ̀, which preceded the Indian Brotherhood’s All Chiefs summit. Before their gathered kin, Dene and Inuit women literally embodied anticolonial resistance integral to Indigenous beauty politics.

Ootes diminishes their brilliance, presenting their pageantry as tangential to the broader agenda of the Indigenous gathering. This is despite having the best of chaperones in Georgina Blondin: erstwhile colleague, former pageant queen, and fierce defender of Denendeh.

Blondin features regularly in Umingmak as an “angry Indian” foil to Hodgson’s “benevolent dictator” (to use Wah-Shee’s term). At Behchokǫ̀, she guides Ootes through the evenings post-pageant celebrations, even leading him through his first round dance. “The temp and repetition of the chant was hypnotic,” Ootes reminisces. “There was simplicity, a power and a closeness to naked creation that moved me more deeply than any other experience I’ve ever had” (p. 238).

Perhaps his memory is faded, but his descriptive powers fail him. Unable to square this demonstration of Indigenous persistence with modernity’s seeming inevitability, he exoticizes Blondin; mistakes life-sustaining ceremony for some primal rite.

Afterwards, Part 4 ambles to its conclusion in 1975. Territorial elections that year result in an Indigenous-majority council, including the now ex-president of the Indian Brotherhood, James Wah-Shee. Together, they lay the groundwork for Canada’s first consensus government. Hodgson, in the twilight of his tenure, presides over the launch of the Prince of Wales Heritage Centre. Ootes, grown restless, resigns his position to return south.

In Part 5, ‘Farewell,” Ootes ponders the commissioner’s legacy. He concludes that Hodgson gifted the territory its “government, the sense of unity, [and] a definition for the world of what a Northerner is” (p. 293).

It is a hollow denouement, for to define a “Northerner” would be to reply to Chief Bruneau’s poignant question, who are you. Ootes circles but ultimately declines to place himself, Hodgson, or the project of government in relation to Indigenous territories and their peoples. Umingmak contemplates but never resolves the dilemma of how to be a guest on stolen lands.

*

Dylan Burrows is an Indigenous Ph.D. candidate at UBC’s History Department. Raised in Nishnaabeg territory in what is now Central Ontario, he lives and works as a guest on the ancestral, traditional, and unceded lands of the Coast Salish peoples. His doctoral research currently focuses on the nature and meaning of Inuit labour under the aegis of Danish, British, and Canadian Arctic exploration and sovereignty exercises during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He lives in Vancouver. Editor’s note: Dylan Burrows has also reviewed books by Deni Ellis Béchard & Natasha Kanapé Fontaine and Alice Jane Hamilton for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster