#974 Maternalists, suffragists, elitists

A Great Revolutionary Wave: Women and the Vote in British Columbia

by Lara Campbell

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2020

$27.95 / 9780774863223

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

Lara Campbell’s A Great Revolutionary Wave is Volume 4 in the UBC Press series Women’s Suffrage and the Struggle for Democracy. Other volumes, by various authors, cover the suffrage movement in Ontario, Quebec, the Prairie Provinces, the Atlantic Provinces, and among Indigenous women, with an overview volume by Joan Sangster, One Hundred Years of Struggle; the History of Women and the Vote in Canada (2018) [reviewed here by Barbara Messamore].

Lara Campbell’s A Great Revolutionary Wave is Volume 4 in the UBC Press series Women’s Suffrage and the Struggle for Democracy. Other volumes, by various authors, cover the suffrage movement in Ontario, Quebec, the Prairie Provinces, the Atlantic Provinces, and among Indigenous women, with an overview volume by Joan Sangster, One Hundred Years of Struggle; the History of Women and the Vote in Canada (2018) [reviewed here by Barbara Messamore].

In 1906 the British Columbia legislature made a mistake while amending the Municipal Elections Act and accidentally enfranchised a number of non-propertied women. An unexpectedly large number of women hastened to register their names on the voters’ list, while the government claimed that was not what they meant at all and set about reversing the change. The reversal did happen and remained in effect for a decade, but not without a fight. In March 1907, Baptist temperance activist and suffragist Cecilia Spofford addressed two hundred people in downtown Victoria. Calling for women’s suffrage at all levels of government, Spofford invoked the movement’s most persuasive and most frequently used arguments; the “maternalist” claim that women’s strong moral character would exert a refining and purifying influence, the “humanist” reasoning that women’s subordination to men was degrading, and the “liberal” assertion that those subject to the law should have a say in the making of the law.

Spofford’s double sponsorship by the Local Council of Women and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union would have surprised no one; the WCTU had been a major vehicle of women’s empowerment since its founding some thirty years earlier. Also not surprising, although exasperating, was the reaction of the male-dominated press:

The solitary male listener who suggested that women were not ready for suffrage encountered such derision that he was “quite overcome by the storm which he had aroused.” A disconcerted Colonist reporter described the behaviour of the boisterous and largely female crowd as characterized by “indignant shrieks of protest” and “hisses like the escape of steam from a boiler with the safety valve tied down.”

It was and is a typical reaction in political debates: if you can’t refute them, ridicule them — and representative of numerous events referenced by Campbell.

The bulk of the book covers the forty-some years 1870-1917. BC joined Confederation in 1871. The municipal vote was granted to property-owning women in 1873-4, and some women began to serve on school boards. In 1916, in response to decades of lobbying and growing support from male politicians and officials, a public referendum was successful, and on April 5, 1917 the franchise was extended to the majority of settler women in BC. In May 1918, the Dominion of Canada granted the federal franchise to female British subjects. Campbell does not allow the story to conclude at that point: “another thirty-two years would elapse before the provincial government allowed First Nations, Japanese, Chinese and Southern Asian women and men to vote.” She worries about this time lapse throughout the book, and with every gain, she reminds us of the remaining exclusions.

The book’s title comes from suffragist, labour organizer, and tailor Helena Gutteridge writing in the BC Federationist (December 12, 1913 p. 7): “The woman and the worker stand side by side,” … the “women’s movement and the labour movement are the expressions of a great revolutionary wave that is passing over the whole world.” A problem with the book is that the revolutionary wave was not what either Gutteridge or the author want it to be.

The various sections of the book recapitulate and revisit the same chronology, a strategy designed to present different aspects of the same story, but often leaving the reader wondering if we haven’t been here before. Wanting to make sure I had the dates correct, I consulted Will Ferguson’s Canadian History for Dummies, (2005). Besides confirming the chronology, Ferguson made several comments relevant to my reading of Campbell: “Although politically radical, the women’s suffragist movement was socially very conservative,” and this — “John A. Macdonald tried to extend the vote to women and Native Canadians way back in the 1880s, but his quixotic proposal was rejected.” [I wonder — Should this be enough to restore the head to Sir John’s statue?]. Campbell admits as early as page 4 that the “early suffragists accepted existing race and property-based exclusions,” but she is not happy about it. She wants her revolutionary wave to sweep over class and race as well as gender, all at once. But even the socialists among her suffragists were unwilling to put their right to vote on hold until after the overthrow of capitalism. On the contrary, whatever their politics, most suffragists agreed that “gaining the vote was essential for wielding political influence.” They regarded suffrage as a tool, a means rather than an end. If the end were justice, their vote would help achieve justice.

At least by the middle of the 19th century, women’s clubs and professional organisations were beginning to realise how effective they could be when uniting to lobby and influence, and how much more effective they could be when wielding the power of the vote. The groups were diverse and included the National Council of Women & Local Councils, the University Women’s Club, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Women’s Liberal Association, the Women’s Press Club, the Women’s Institutes, the Pioneer Political Equality League, the Political Equality League, the BC Woman’s Suffrage League, the Women’s Social and Political Union, the Equal Franchise Association, the Equal Franchise League, the Chinese Empire Ladies Reform Association, and the Women’s Forum. They had diverse reasons for existing, but most “believed in both the spiritual superiority of Christianity and the cultural superiority of Britishness.” Campbell admits that while it seems clear in the light of presentism that the movement’s arguments for equality rested on a “deep feeling of British superiority and entitlement,” at the time British settlement was seen “as an affirmation of hard work and egalitarianism rather than the dispossession of Indigenous land.”

Women’s organisations flourished not just in major centres, but around the province in towns like Kelowna, Enderby, Revelstoke, Nanaimo, Lillooet, Burnaby, Vernon, Nelson, Enderby, and Fernie. Unlike their sisters of the British suffragette movement, Canadian suffragists avoided sensational tactics and direct action, but they found ways to capture media attention and press their arguments in a culture of open debate. The chapter “Performing Politics” tells of their use of drama, humour, and satire, mixing entertainment with education in such events as Mock Parliaments, debates, speaking tours, petitions, meetings with politicians, letters to the press, and incessant lobbying. They seldom staged their own parades but routinely participated in civic events like the Labour Day parade and booths at fairs.

“Co-operate, agitate, educate, vote, legislate.” Such was their plan of action as articulated by Nellie Craig of the Pioneer Political Equality League in the Vancouver Daily World of November 24, 1913.

For a while there were two dedicated suffrage publications in British Columbia, in fact the only two in Canada. The Pioneer Woman, launched by Helena Gutteridge, foregrounded the concerns of working women. The Champion was the official journal of the BC Political Equality League. Even when they could not sustain independent publications, the contributors persisted in such organs as the BC Federation of Labour newspaper, The Federationist, and in The Western Methodist Recorder, and, whenever they could, infiltrated the columns of the mainstream press.

Cameo biographies spotlight individual suffragists, for instance: Maria Pollard Grant for a time “the best-known BC suffragist …,” a founding member of the BC chapter of the WCTU and other early suffrage organizations; Mary Ellen Spear Smith, the first female MLA and cabinet minister; Cecilia McNaughton Spofford, the energising speaker mentioned above; Florence Sarah Hussey Hall, founding President of the Vancouver Political Equality League; Helen Gregory MacGill, journalist and judge; Martha Douglas Harris, daughter of Governor James Douglas and a founding member of the Victoria Political Equality League; Helena Gutteridge, one of Campbell’s heroines; Evlyn Fenwick Farris, not one of Campbell’s heroines despite her energetic forwarding of the suffragist cause; and Agnes Deans Cameron, whose image graces the book’s cover, the first woman to teach high school in British Columbia and first female principal of a public school.

The suffragist movement was less a matter of women versus men than of women with men, and Campbell recognises some prominent male supporters. Former fur trader Dr. William Fraser Tolmie declared that female enfranchisement was “a modern inevitability” and in 1875 introduced an amendment to the Voters’ Act. For John Robson, premier 1889-92, support for women’s suffrage “was rooted in his Christian faith and commitment to both temperance and representative government.” MLA Joseph Martin commented in 1902 that “there was no possibility of women making a worse mess than men had done.” L.D. Taylor, long-time mayor of Vancouver and owner of the Vancouver World offered a column to activist Susie Lane Clark. There were many others — of course, or the legislation would not have passed in 1917.

But Campbell tends to pick and choose examples, and is not always consistent. She praises Conservative Member of Parliament H.H Stevens for his support of suffrage, but overlooks his role in the Komagata Maru incident in 1914 and ignores his lifelong influence on the federal government’s anti-immigration policies. She reacts with surprise and disappointment to learn that in 1917 he defended the exclusion of “alien female voters,” and yet this action was consistent with those taken throughout his career. Then there is Attorney General J. Wallace Farris who worked closely with MLA Mary Ellen Smith in support of women’s empowerment; but Campbell balks at giving any credit to his wife Evlyn, whom she repeatedly describes as “elitist” and omits them from her list of “companionate and co-operative marriages” in which spouses worked together for the cause.

Anti-suffrage activists on both extremes of the political spectrum maintained that woman’s place was in the home. Those on the far left believed that all available political energy should go towards achieving revolution, and that once capitalism was defeated, justice would reign and women’s suffrage would be unnecessary — an argument which still seems singularly unconvincing. On the right, MLA A.E. McPhillips worried that the comparatively mild-mannered Victoria suffragists might emulate the women of the French Revolution marching “through the streets, on the barricades, at that pitch when all idea of morality, and of propriety had been lost.” One imagines Martha Douglas Harris and other members of the Women’s Institute Weavers Guild knitting alongside Madame Defarge.

There does seem to have been a real fear that enfranchised women would force their husbands to help with housework and that this would be a bad thing: “Being forced to do the laundry seems to arouse great discomfort.” Many women shared the belief in separate roles for men and women. “Women’s place is in the home and every woman should have one. It is her business to get one,” said Mrs. Homan Childe: “They can all find some kind of man to make a home for. Anyway, the more I see of the men God put into the world, the more convinced I am that God did not intend us women to be too particular.” That argument also seems unconvincing. In response to claims that enfranchisement would distract women from their duties as wives and mothers, the Champion imagined the fictional “Knights of the Square Box.” This association would deprive men of the vote, because “it unfits them for business life and distracts them from the far more vital matter of Real Estate Transactions.”

The book’s organisation by chapter topics such as race, the labour movement, and global context works to an extent, as long as the chapters are not read in quick succession, but exacerbates the chronology problem mentioned above. Here are a couple of examples. British suffragette and public speaker Barbara Wylie tours Canada in 1912-13, but on the following pages the speaker is the American Susan B. Anthony and the year is 1871; in a few pages we are back to Wylie. Among those present for Wylie’s speech at Vancouver’s Labour Temple in 1913 was Rev. Henry Edwardes of St. James Anglican Church. I learned about him years ago through my research on the parish and was pleased to find him in this unexpected company. An active member of the Vancouver Political Equality League, Fr. Edwardes appears at least three times in the book, once remarking that the women of British Columbia had less political power than the women he had met during his missionary work in “Darkest Africa.” Two of the three appearances turn out to be at the same event. Moreover, his name is consistently misspelt without its second “e” — an error traced to Campbell’s reliance on secondary sources such as newspapers, in this case the Vancouver Daily World. A small matter in itself, but how many other such errors did I miss?

That said, I am not sure how else Campbell might have organised her material. Her discussion of the “politics of race” includes interesting sections on Indigenous and African-Canadian women. But she cannot stop wanting the women of a century ago to think as she does. “North American suffragists were unwilling to link enfranchisement with ending colonial rule, lifting restriction on Asian immigration, or criticising the dispossession of Indigenous peoples.” Even when people seem to have acted with the best of intentions, she tends to assume the worst. A petition to Premier McBride in 1913 refers to “women of the Race.” I take this to mean the Human Race, as in the lyrics of the revolutionary anthem The Internationale, but Campbell seizes on the word to provoke another discussion of racism. The chapter “Labouring women” grapples with the sexism within socialism. “During the first decade of 20th century BC had the highest percentage of women who worked after marriage, who were self-employed, or who worked in the professions,” but there was a conflict of interest and for socialists “achieving a family wage and preserving high wages for white settler men remained of utmost importance.” And so because of the “fragility of suffragist alliances with socialist parties and unions,” suffragists continued to work within independent women’s organisations, and working women were doubly oppressed by class and gender.

The Great Revolutionary Wave is further conflicted over questions of maternal and child health, questions still not fully answered. Campbell’s analysis of various forms of women’s participation in public and private life leads to an engrossing look at the coal-mining towns on Vancouver Island.

The chapter “A Global Movement” puts BC suffragists into part of a larger community, in touch with international speakers until War made travel difficult – a point made twice twenty pages apart. The direct action overseas “shook conventional assumptions about how far women would go to secure political equality,” even if BC women had not – yet — gone so far. Less expected than the pages about the UK suffragettes are the pages about the women’s movement in China and its international implications.

Chapter 8, “Achieving the vote,” is the most exciting in the book, balancing partial victories with ironies and unintended consequences, and the paradox of dependence on men’s votes to pass the referendum which would give the vote to women. The referendum passed, what then? As the state granted more demands for social justice, did it also deepen its control over our lives? How did achieving the vote inspire continued activism? The vote was never a solution, only a means to solutions, and there were no unanimous gender-based solutions to social issues such as alcoholism and prostitution.

The questions carry on into the chapter “Extending Suffrage” where the author gives free rein to the cause which has been foremost with her throughout: the completion of the goal of “universal suffrage.” The section opens with a photo of Frank Calder, the first Indigenous person to serve in the legislature and the only man to have a solo photo in the book; important though he was, one wonders why she did not choose a woman as token non-European, perhaps Judi Tyabji or Melanie Mark, both of whom she mentions.

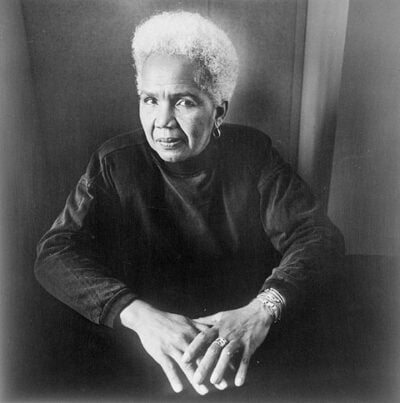

Campbell concludes the book with a tribute to Rosemary Brown, the first black woman to hold a seat in the BC legislature. The tribute is much deserved but Campbell’s enthusiasm raises some questions. Why is Rosemary Brown’s activism presented as authentic and that of Evlyn Farris as inauthentic? The term “elitist” is repeatedly associated with Farris. And yet both came from Middle Class families, attended university, practised professions, married professional men, actively supported political parties, and were members of the University Women’s Club. Brown achieved more obvious political success in her own right, but she benefitted from the power fought for and won by Farris and her contemporaries two generations earlier. Brown’s own contemporaries Marguerite Ford, May Brown, and Grace McCarthy are not mentioned. What sets her apart is her race. Without in any way underestimating Rosemary Brown’s splendid achievements on local, national, and international stages, I wonder if the author in her anxiety to cover every angle might have stumbled into a sort of reverse racism. Campbell admits that Brown herself “passionately expressed her commitment to the emancipation of everyone regardless of gender, race, class, or age.”

Women in British Columbia and elsewhere have held this powerful tool, the franchise, for more than a century, and yet every few years we have to decide all over again how best to use it — a dilemma shared by our fellow citizens of whatever gender. Campbell should not worry so much about her predecessors who did not make the choices she would have them make; as she concludes, a “vision of liberation and equality remains a work in progress to this day.” Suspicious of the currently fashionable division of feminism into separate “waves,” she writes that such division “misses the fact that feminist successes, failures, and hopes have remained an ongoing conversation. Movements for social change are always partial and incomplete, Feminist approaches to solving inequality remain ongoing projects, partly because our understanding of gender is always changing in response to the world around us.” Her book makes a valuable contribution to the understanding of herstory.

Now I am off to read the volume about Quebec, the last province to achieve women’s suffrage and the first in which I cast a vote. My daughter in Quebec City has reminded me that after the Constitutional Act of 1791 women property-owners had the franchise — until it was taken from them in the years 1834-1849 not least by the efforts of the legendary Patriote leader Louis-Joseph Papineau. It is so difficult to find a flawless hero/ine these days.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications, including the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: for The Ormsby Review Phyllis Reeve has reviewed books by Connie Greshner, Ken Lum, Susan McCaslin & J.S. Porter, Ian Hampton, Robert Amos, Joe Rosenblatt, Eileen Curteis, Naomi Wakan, among others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

4 comments on “#974 Maternalists, suffragists, elitists”

I’m glad to see the reviewer had trouble with some inconsistencies… so did I! It’s important to flag these in a review since otherwise someone not familiar with the topic might make assumptions about the content of the item under review.