#972 Sea wolf of Discovery Island

Takaya: Lone Wolf

by Cheryl Alexander, with a foreword by Carl Safina

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2020

$30.00 / 9781771603737

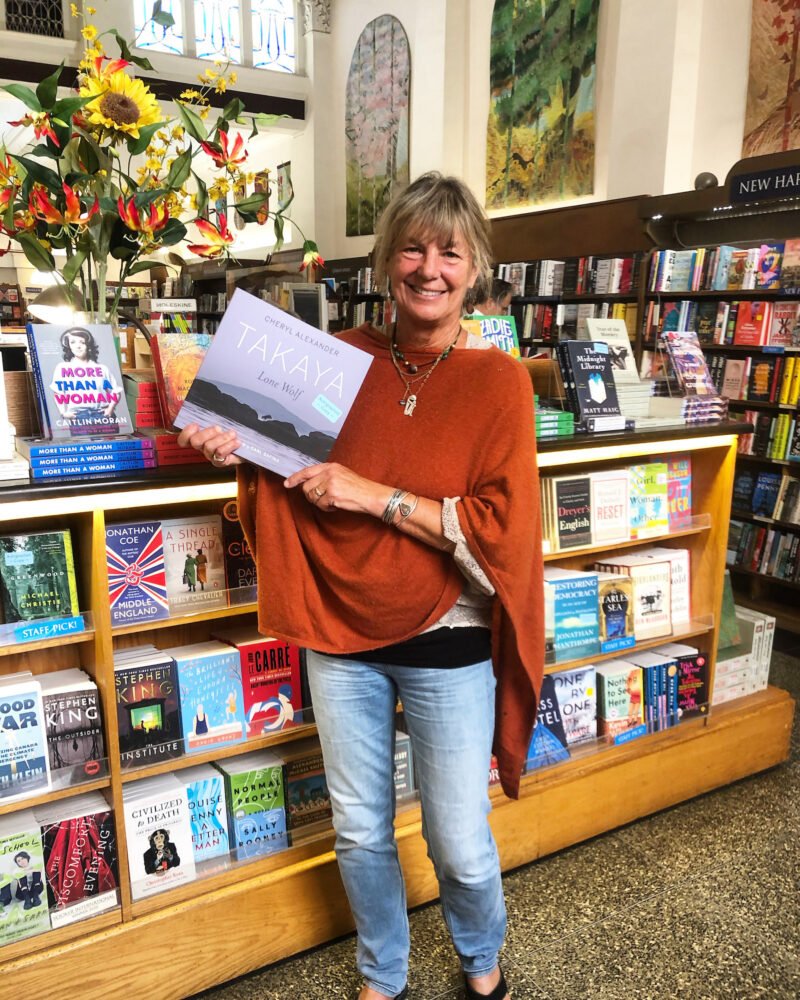

Reviewed by Luanne Armstrong

*

When I was a child, I lived far more intensely with animals than I did with people. As the somewhat feral daughter of homesteading farmers, I found animals were far easier to deal with than people. When I discovered reading, I began to read every animal book I could. In every book the animals were smarter, kinder, and better than people, which only confirmed my bias. I still read a lot of books about animals and follow the scientific research showing that animals are far more intelligent and empathetic than was previously assumed.

When I was a child, I lived far more intensely with animals than I did with people. As the somewhat feral daughter of homesteading farmers, I found animals were far easier to deal with than people. When I discovered reading, I began to read every animal book I could. In every book the animals were smarter, kinder, and better than people, which only confirmed my bias. I still read a lot of books about animals and follow the scientific research showing that animals are far more intelligent and empathetic than was previously assumed.

But despite such achievements in research, when wild animals come into contact with human beings, it usually ends badly for the animal. Cheryl Alexander’s Takaya is a sweet book with lots of beautiful pictures. Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on what you want to know), it was published before the news came that Takaya had been shot just after he was re-located to somewhere on Vancouver Island.

Takaya was definitely an oddity in wolf world, a lone wolf who somehow swam across the sea from somewhere and landed on Discovery and Chatham islands, part of Discovery Island Marine Provincial Park, not far from the city of Victoria. Despite visiting tourists and occasional dogs, he stayed and successfully eked out a living by killing seals and eating washed up carcasses of other sea animals.

Cheryl Alexander set out to document his existence, take photos of him, and carefully try to get to know him. In this, she deserves credit. She seems to have been respectful and kept her distance (although, if I were Takaya, I would have felt stalked by her, but I’m not a wolf), and he seems to have slowly gotten used to her. For over six years, he lived alone, although most wolves live in families and have a hard time living outside of the shelter and support of a wolf pack.

But then something slipped for Takaya. He left the islands, and ended up in downtown Victoria, where he was tracked, eventually tranquillized, moved to a new area, and then shot by a hunter. There was indeed a big hullaballoo on social media about it at the time, many people demanding he be saved and then left alone. What irritated me is that while many people on social media were bemoaning Takaya’s sad fate, the BC government was trapping, shooting, and destroying over 500 wolves in the BC interior. Somehow the support for Takaya’s life did not translate into support for the lives of other wild wolves.

Alexander’s book does not take on weighty issues of conservation or habitat or wolf research. She sticks to her story; she meets a wolf, she takes a lot of really beautiful pictures of him, and he gradually relaxes in her presence. Her style is mercifully free of superficial sentimentality, except for a few moments when she manages to look into his eyes, and sees that he has taught her to sit still and observe the world around her. Only in the last chapter, “Takaya’s Gifts,” does she allow herself to rhapsodize about this lonely wolf. “The story of Takaya is epic, heroic, and an odyssey that ignites our collective imagination and awe. It is a story of resilience, survival and adaptability. It is the story of compassionate co-existence.”

Well, maybe.

Alexander mentions in passing some of the deep research that has been done on wolves, by such terrific BC writers such as the great Ian McAllister in The Last Wild Wolves: Ghosts of the Great Bear Rainforest (Greystone: 2007), and Paula Wild in The Return of The Wolf (Douglas and McIntyre, 2018). Small bits of such research make it into this book, enough that I will happily gift it to my nine-year-old grandson who is fascinated by animals.

But in general, and rather sadly, this book does nothing much to add to our knowledge of wolves or wildlife. The fetishization of individual animals into either the cute and cuddly camp, or conversely the wild and scary camp, does little to help the plight of the world’s animals, which are still being killed off at an astounding and horrifying rate. Such fetishization and binary thinking echoes the oppressive division of women into saints or whores, or Indigenous people into noble or degraded. There has yet to be a wide recognition that animal lives, and animal habitats, indeed do matter very much and that animals have their own rich cultural lives that have nothing to do with humans.

I am glad of course that Takaya had the peaceful life that he had, even though it ended in a moment of utter cruelty. But I would urge people who truly care about animals, biodiversity, and a fairer and juster world, to learn about the true research that is being done on animal sentience and animal culture and language. For example, it is known now that dolphins all have individual names, that crows teach their babies who is a safe person and who is not, that grey parrots can do arithmetic, and that chimpanzees recognize themselves in a mirror (as do many other animals.)

When I go to visit my horse now, I have learned from such research that horses have seventeen (or more) different facial expressions and that they recognize human expressions as well. I try very hard, as I have tried all my life, to learn from the animals I interact with, such as my horse. But I still get it wrong. For example, the last few times we went for a ride, I knew he was trying to tell me something, but wasn’t sure what, until the vet came and diagnosed him with a very sore back. So he gets time off now and I get to bring him treats and apologies.

Humans are still very muddled in their ideas and approaches to animals. As people get more urbanized their opportunities to meet real wild animals are few and so instead they fuss over their beloved “pets.”

Mostly, stories about animals are about the people in the stories, not the animals. As is Cheryl Alexander’s book. The pictures are beautiful. The story verges on the edge of sentimentality, but thankfully never quite falls over that edge. It’s told with sincerity but not much more.

Perhaps Alexander learned something from Takaya beyond sitting still. And perhaps this book will persuade some readers to do some further research on wild wolves and even join in the effort to get governments and hunters all over North America to quit killing them.

*

Luanne Armstrong has written 21 books including young adult, fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. She has contributed to many anthologies and edited Slice Me Some Truth (Wolsak and Wynn, 2011), an anthology of Canadian non-fiction. She has been nominated or won many awards, including the Moonbeam Award the Chocolate Lily Award, the Hubert Evans nonfiction Book award; the Red Cedar Award, Surrey Schools Book of the Year Award, the Sheila Egoff Book Prize, and the Silver Birch Prize. Luanne lives on her hundred year-old family farm on Kootenay Lake. She mentors emerging writers all over the world on a long-term basis, and in the last three years has edited eight books through to publication. Her most recent books are Sand (Ronsdale Press, 2016), and A Bright and Steady Flame: The Story of an Enduring Friendship (Caitlin Press, 2018; reviewed by Lee Reid). Armstrong is now working on a book of essays, Going to Ground, as well as a new book of poetry, When We Are Broken. Editor’s note: Luanne Armstrong has also reviewed books by Wayne Sawchuk, Katie Mitzel, Tom Lymbery, Richard Vission, Deni Béchard, Robert Bringhurst & Jan Zwicky, Briony Penn, Ann Kujundzic, and Lee Reid for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster