#967 A great gathering of empire

Orphans of Empire

by Grant Buday

Victoria: TouchWood Editions (Brindle & Glass), 2020

$22.00 / 9781927366899

Reviewed by Laurie Ricou

*

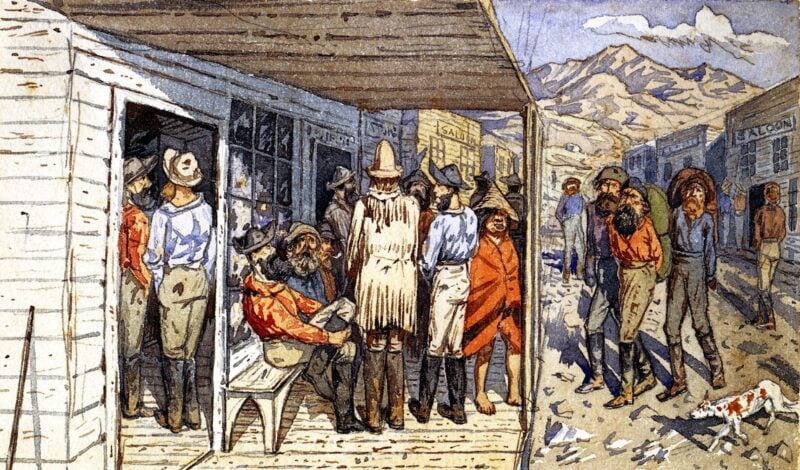

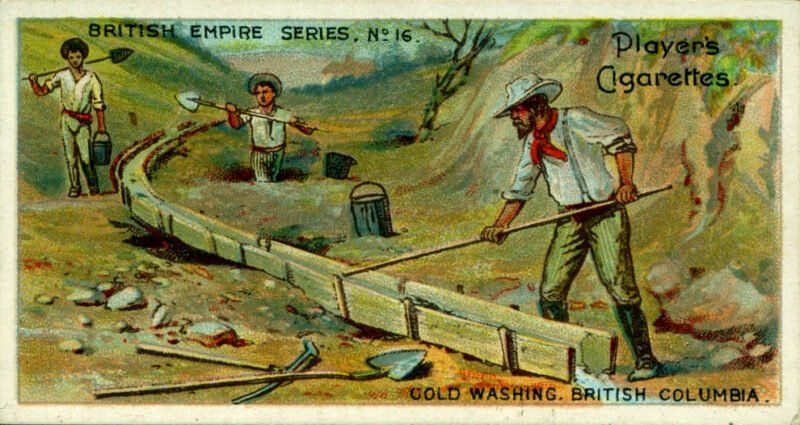

Grant Buday’s exuberant novel contemplates an emerging British Columbia in the second half of the nineteenth century. As his title signals, Buday tests claims of possession and supremacy, in institutions, occupations, and personalities. In one instance, extending the imperial trope, he re-imagines the slightly villainous Ned McGowan, having wearied of the sometimes comic clashes between British and American miners at the Hill’s Bar gold rush site on the Fraser, announcing his return to the United States with the assertion that “‘[t]here are as many empires as there are men.’” The novel’s cast of characters also implies an inverted proposition: that there are as many orphans as there are people (even creatures).

Grant Buday’s exuberant novel contemplates an emerging British Columbia in the second half of the nineteenth century. As his title signals, Buday tests claims of possession and supremacy, in institutions, occupations, and personalities. In one instance, extending the imperial trope, he re-imagines the slightly villainous Ned McGowan, having wearied of the sometimes comic clashes between British and American miners at the Hill’s Bar gold rush site on the Fraser, announcing his return to the United States with the assertion that “‘[t]here are as many empires as there are men.’” The novel’s cast of characters also implies an inverted proposition: that there are as many orphans as there are people (even creatures).

The idea that empires orphan their children might be the thesis of this novel, but it is seldom explicit. Where it does emerge, almost incidentally, it gains power by being muted, as when nine-year-old John Moody explains his apprehensions about “Natives”: “Because we kill them, …. And we take their land.”

Empires aggregate. They embrace and elide multiple nations, myriad places, radically different cultures. Given this impulse to expand, perhaps, Buday recognizes that the story of occupying the western edge of North America requires a great gathering. Accumulation permeates the stylistic of the novel. The intensity of the lists is absorbing. At almost every turn — of narrative, scene, or character — the impression mounts of disparates cohering in a dense cluster.

Relatively compact scenes and layering take priority over plot and narrative. The novel as a whole searches for a companion strategy of swirling aggregation, a congregation of tales and scenes: a study of costume here, a detailing of architecture there, a description of economic enterprise here, an enthusiasm for interiors there. Buday’s form is somewhat anecdotal, and somewhat random. Thirteen titled sections feature three defining figures: Colonel Richard Moody, eighteen-year-old Frisadie, Kanaka housemaid from Hawaii, and Henry Fannin, shoemaker and naturalist. We encounter them at shifting times from 1858 to 1886, in shifting locations. Printers’ devices further divide the diary-like “chapters” into numerous vignettes and sketches. And a considerable host of other characters are attentively included — for example, Moody’s wife is as important to the ethics of colony building as is her husband with his official titles. Buday’s composite portrait of settlement insists on the mix of psychologies and cultures that “history” involves (or ignores) — to both good and bad effect.

In one of his myriad lists, Buday describes George Black, pioneer landowner:

A sportsman, Black raced horses, played field hockey, football, rugger, and cricket, ran sprints, put the shot, hosted Sports Day each year on the first Sunday after the summer solstice, and held fortnightly roller skating regattas for the children at which he supplied the skates and treats (p. 109).

Ten recreational activities in one sentence build, economically, a portrait of character, but also of culture and calendar and childhoods and play. Such list is a sidebar to the stories of orphans and empires, but essential to the culminating density of the world he documents and invents. One scene on New Year’s Eve, has Harry Hearne, journalist who is describing the New Brighton hotel for the Daily British Columbian, trying a sentence, and then listing (almost chanting) six alternative syntactical variations of the same line. Hearne is tormented by his passion for “the rhythms of his prose.” So much so that at the end of his inebriated singing of syntax, he gets “down on all fours and groaning, pressed his face into a patch of snow to cool his brow and freshen his brain.” Such physical devotion to the compelling suppleness of prose hints at the novelist’s ironic play on his own love of accumulation.

Frisadie, distraught by the sudden disappearance of her husband Maxie, catalogues seven degrees of ecstatic love that elude her. This inventory then leads her to ponder eight forms of love, including the love of nature, and the love of music. Her reflections turn more abstract: “So many voices speaking the word love made her wonder if those various loves had their own shapes and colours, blue love, red love, grey love, green, even black.” Such accumulation continues in various registers. Seven random articles from The British Columbian. A compilation of a dozen and more habits and talents of Governor James Douglas. A ten-line sentence traces Henry’s fantasies of flying with Leonora. And this flight is followed immediately by a paragraph-long sentence recording some 16 of his soaring cosmic dreams.

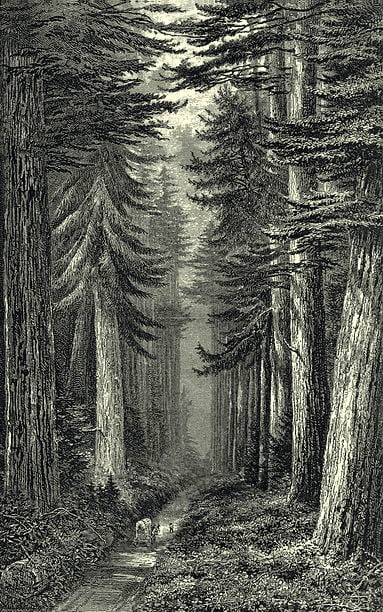

For this reader, the novel’s appeal lies not so much in subtle depths of character, nor a compelling chronology, but in the intricate texturing of physical and cultural place. Maybe those orphaned by empire nonetheless find home and some measure of parental support in a density of sensory experience. “The firs,” Buday observes, “were certainly imposing, thick, dark, towering, almost sentient, as if aware of their power to dominate and exulting in such terrible strength.” He is alert to such thick sentience at every turn: “Gas lamps hissed an odour of coal and ammonia that blended with the smell of crushed flowers and something low and faintly nauseating but nonetheless intriguing.” Sensation startles in his metaphors: Moody, taking his seat on the Beaver, “sank down like a wick subsiding in wax.” It’s reinforced by a zest for an archaic vocabulary (such as “gick”) or the jargon of navigation (“tars” and “bollard”). Something of the upholstered style of the Victorian novel lingers here. But more tellingly, I think Buday is at play, losing himself in the patterns of words animating BC spaces for the sheer delight of it.

Fittingly the novel’s final scene depicts Moody’s son John, their dog Hilda, and eventually Moody himself running into the sea to join a pair of seals in a frenzy of play. It’s a celebration of place that fuses cogitation and an imperative to “liven it up.” They go adventuring playfully as the novel surely does. Buday plays as he learns, and we learn as he plays.

*

Laurie Ricou is Professor Emeritus of English, UBC. His books include The Arbutus/Madrone Files: Reading the Pacific Northwest (NeWest Press and Oregon State University Press, 2002) and Salal: Listening for the Northwest Understory (NeWest Press, 2007).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#967 A great gathering of empire”