#909 Twilight of the club scene

Vancouver After Dark: The Wild History of a City’s Nightlife

by Aaron Chapman

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019

$32.95 / 9781551527833

Reviewed by Grahame Ware

*

On March 12, 2020, Aaron Chapman’s Vancouver After Dark was one of five books shortlisted for the 2020 Bill Duthie Booksellers’ Choice Award of the BC and Yukon Book Prizes. Winners will be announced on September 19th — Ed.

*

Let’s be honest: Aaron Chapman does not especially need a review of Vancouver After Dark. You probably know its been flying off the shelves of Vancouver bookstores. At least it was until Covid came a calling. A first printing of 5,000 copies late in 2019 lasted just two months before a quick second printing was happily flashed together. Now the hourglass again has more sand in the bottom than the top and a third printing seems possible. This is terrific stuff for a “local history” book.

Let’s be honest: Aaron Chapman does not especially need a review of Vancouver After Dark. You probably know its been flying off the shelves of Vancouver bookstores. At least it was until Covid came a calling. A first printing of 5,000 copies late in 2019 lasted just two months before a quick second printing was happily flashed together. Now the hourglass again has more sand in the bottom than the top and a third printing seems possible. This is terrific stuff for a “local history” book.

Vancouver After Dark is Chapman’s third book about Vancouver’s temples of decompression. It covers a diverse number of Vancouver nightclubs over the 20th century, especially post-1945. It will have broad appeal. Chapman and his team at Arsenal Pulp Press have found the groove and succeeded beautifully in detailing the stories of the places Vancouverites went to have fun. Buttressed admirably by strong graphic material, Vancouver After Dark really is a smorgasbord of a book. Chapman’s style is journalistic rather than scholarly and he uses reports and interviews instead of a more lyrical, essayistic approach.

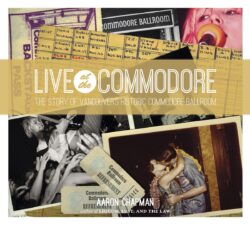

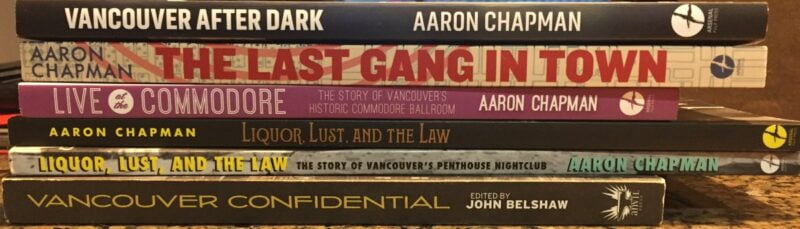

Given his background as a musician and band manager, Chapman is firmly in control of his own wheelhouse. He started his writing career as a journalist at the Vancouver Courier, where he had a column called “Backstage Past,” and the rest, naturally, is history. It just went from there. Two previous books, Liquor, Lust, and the Law (2012) and the prize-winning Live at the Commodore (2014), both published by Arsenal, concerned the buildings, landlords, and the often-young impresarios who dared drag Vancouver out of its wartime and conformist doldrums and entertain them — or, better still, stimulate them to think.

No one would have thought that this Kerrisdale kid and Point Grey Secondary School graduate would be where he is today, a leading social historian of Vancouver, but don’t put anything past Aaron Chapman. He’s no polymath but he’s energetic and versatile. As a not-untypical intellectual malingerer, he felt the need to indulge his scholastic divertissements. So he took his time at UBC. He spent more than the usual four years to snag his BA with a major in Film. More students should do this. And all the intellectual curiosity and training has paid off in his writing.

A good collaborator, Chapman was able to enlist participation from music history wonks around town. Consider the visuals he got for Vancouver After Dark from Rob Frith of Neptoon Records. Amazing! He tapped journalist John Mackie big time and, by his own account, incessantly emailed Vancouver Sun archivist Carolyn Soltau and her SFU Special Collections compadre, Melanie Hardbattle. They gave and gave and gave. Mr. Persuasion is in the house! Chapman acknowledges them and more in the book, so he’s no ingrate.

Chapman is also a real promoter: a journalist-as-historian seeking to make a living from his work. To stir interest Arsenal allowed him to feature whole sections of his book to The Georgia Straight, The Tyee, the Vancouver Sun, and his old paper, the Vancouver Courier. This was back in the late pre-Covid era, in late November-early December 2019, when I was waiting (im-) patiently for Arsenal to send me a review copy. Then around Christmas, Chapman was on Global News with Squire Barnes (whom he thanks in the book) for a 3-minute spot on “BC’s most watched newscast.” And then, on a micro level, he spent three hours on Nardwuar the Human Serviette’s show on CITR-FM. Three hours! I know. I listened to it.

And if that wasn’t enough, after the second printing became available, Chapman was Johnny-on-the-spot pumping it. He popped up on TEAM 1040 with Donny Taylor and the “Moj” radio show because Donny’s brother Gary has been an entertainment impresario for decades. Gary Taylor is the subject of extensive interview in Vancouver After Dark. Chapman’s kind of commitment is terrific in the grandly homogenized scheme of all things media. He certainly has people thinking about what kind of cultural scene they have, and might want to have, in Vancouver.

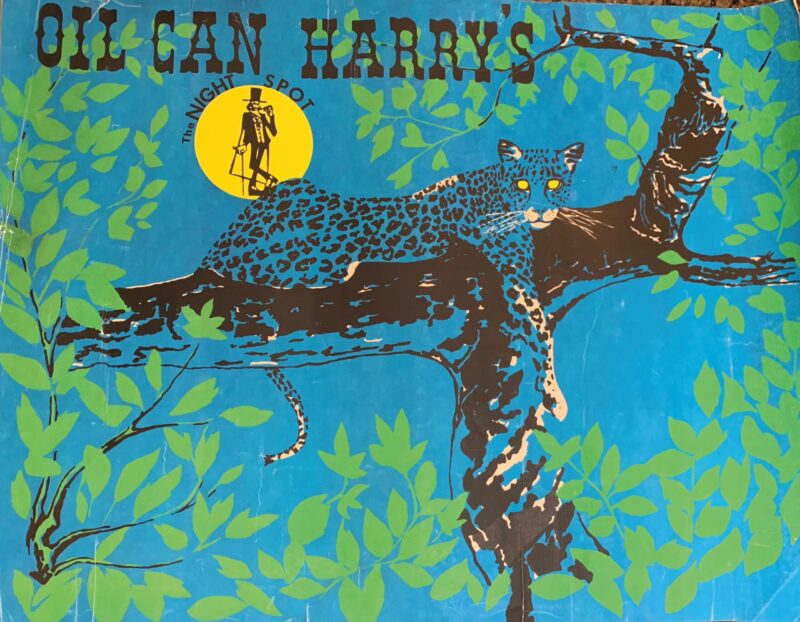

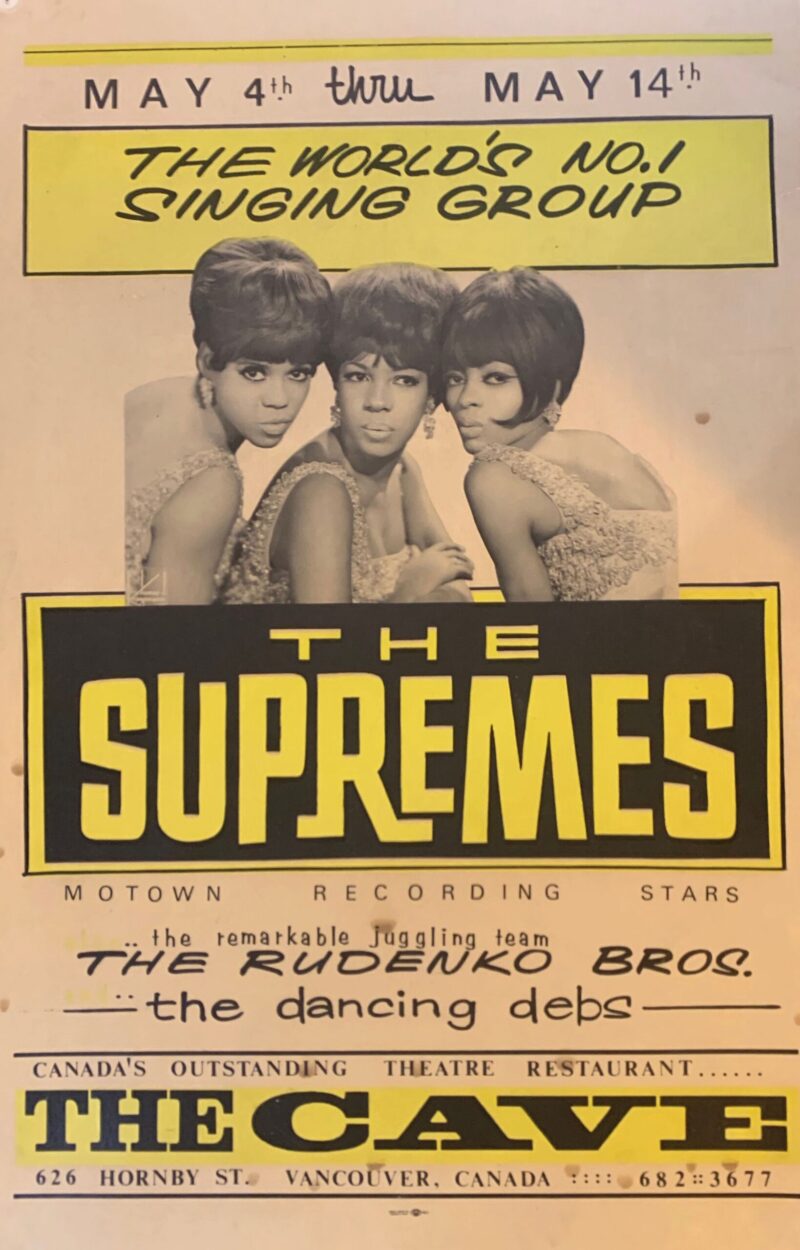

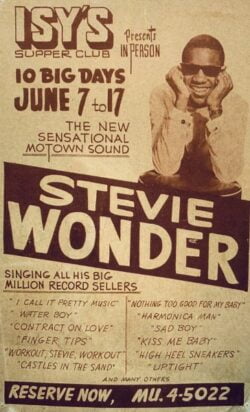

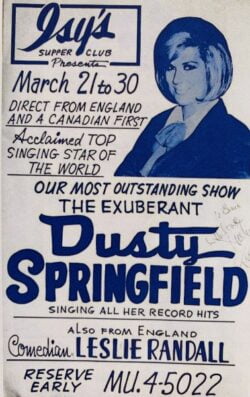

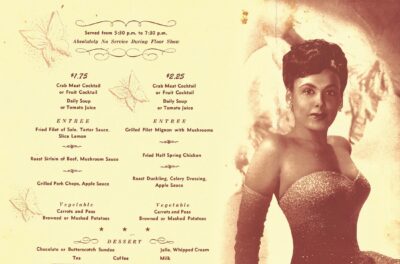

Building on buildings, Chapman takes up after his earlier paeans to the Penthouse and the Commodore. With apologies to Freud, you might say that Chapman — like many local historians — has an edifice complex. Vancouver After Dark is a continuation of this arc and the last in the trio; it’s all the little leftovers (and then some!) from working on his previous two books of Vancouver history. At least half of the book is taken up with archival pictures and handbills and posters from Neptoon Records. The format, art design, and colour reproductions make for a very appealing production: an easy romp with an almost comic book-graphic novel style romp. When dealing with history, this is not a bad thing at all. In short, this is a smart-looking book that reads well and deservedly puts itself in a position to win some awards for popular history.

*

The Hall of Fame R & B man James Brown used to bill himself as the hardest-working man in showbiz. Well, Chapman might just be the hardest-working popular historian in Vancouver. Vancouver After Dark is replete with all the dirty details of a vast array of clubs and the many transmogrifications they went through before becoming real estate dust. While Chapman isn’t a particularly lyrical writer he is a hard worker and a more than adequate journalist who tells a good yarn and provides invaluable minutiae about a galaxy of entertainment hangouts.

But if you were expecting Tom Harrison or Alex Varty to flesh out the stories of what music actually happened and why people turned out, you might be disappointed, though Harrison contributes a whole scanned column of a 1981 performance by Johnny Thunders (“Thunders but no lightning,” p. 129).

On the other hand, club owners who are still alive are given preference in some extended interviews, as are some musicians themselves. Thus, the book’s lens is largely filtered though the owning-renting class rather than winnowed through the visceral mesh of the mostly working class or the neo-middle class. In fact, back then everybody in Vancouver’s club scene seemed to come from the same cultural cauldron. The people that went to these clubs had a reason to go out. Why? Because it was a “value proposition”! Why wouldn’t they go?

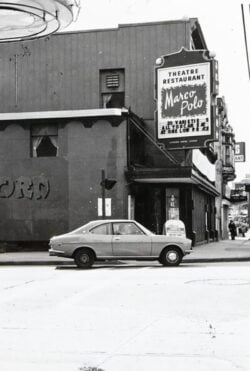

Denny Boyd, in lamenting the closure of Chinatown’s Marco Polo Theatre Restaurant in 1982, as well as the state of entertainment in Vancouver more generally, recalls that:

You could go downtown with a $20 bill in your pocket and see a class act. Uptown we got the major acts at the Cave and Isy’s. Downtown we got the new acts, plus gold coin beef and steamed broccoli at the Marco Polo…. they worked hard there and they respected your entertainment dollar. It was a fun place and there aren’t any fun places left. Maybe I’m missing something. Maybe Vancouver doesn’t want to chuckle anymore. Maybe the climate’s too wet and the economy too dry for laughing. All I know is, I never saw a bank tower I liked (p. 58).

But Boyd is not expressing “cautious optimism,” as Chapman opines. Rather, he is bemoaning that the life and the fun have drained out of the scene he knew and loved.

In the same vein, Chapman doesn’t make enough of the fact that the newspapers and weeklies like the Georgia Straight had journalists who gave timely and interesting reviews to the clubs and acts. They kept Vancouverites in the loop and excited about “catching” an act. This included Alex MacGillivray, Denny Boyd, Bob Smith, and Jack Wasserman from an earlier era, and Tom Harrison and Alex Varty more recently. They were given column space to describe and write about their experiences. Who is there now? The Straight? The Tyee? Groan.

Is not this decline in local expertise one of the main reasons the music and entertainment scene is withering? Certainly the “system” is not communicating with itself to the degree that it used to, and has abdicated the hard work and responsibility of venturing independent and expert opinions as arbiters, judges, and critics of talents and experiences in the manner of the aforementioned media and writers. The corporations have abandoned the people, plain and simple.

Facebook and Twitter are but empty digital megaphones decentralized to the point of meaninglessness, no matter how many claims of the virtues of peddling click bait and “going viral” (to or for whom?). If people want to believe in this easily manipulated, often bot-driven info, they do so at their own peril. Why should I step out my door and drive on into a club to experience a live performance when I can get a filtered/edited performance for free on YouTube?

Where is the communal experience where one talks about the food or the drinks or the E [Ecstasy] at Club 2Fly? Is this the final step in alienation, where we’re just one step removed from AI (artificial intelligence) in having a “better” experience? Where we can have more “fun” with some “thing” rather than with someone? Young local dreamer impresarios — bursting to provide a club and a context for music or art or dramatic performance for other local dreamers – have been replaced with not-so-local, corporate techno organizers streaming off-the-shelf commodities to anyone with a cell phone and headphones. In fact, we’re streaming ourselves into a corporate oblivion. This is where Stephen Sondheim’s 1973 ballad “Send in the Clowns” was presciently updated to “Send in the Clones.” On the other hand, what would a great club be without raving, manic fury, and the mandatory throwing up in the back alley after dropping $100 on food ’n drinks. Oh migawd, don’t deprive me of that! What about that “Youth will be served” moment? Young impresarios’ dreams are likely to get crushed when a city can’t support even mildly successful and commercially artistic events.

It is too pat to suggest — as Chapman does — that “every generation thinks that their time in the youthful sun” was the best, and that something else will come along for the evolving generation who will, in turn, snarkily declare that the previous generations didn’t know diddly-squat. Of course this assumes that the cultural programming and consumer habits will be intact and that the socio-political macros remain unchanged. This is a faulty assumption.[1]

Dreams get squashed when a city is unable to support even mildly successful and commercially artistic events. “Go big or go home” has never had a more sinister ring to it. What does it say about our culture when people splash down thousands of dollars for an Elton John ticket? Developing an “audience” is a tricky thing. A return to church basements and community halls as venues for the performing arts seems inevitable.

*

So why is a UBC film school graduate and tin whistle-playing Celtic rocker doing books like this? We talked to Chapman via email recently and this is what we found out.

Interview with Aaron Chapman

GW: What was your major?

AC: I studied Medieval History and Religious Studies, but switched majors and went to UBC Film School, so I ended up with a Film degree. I had originally wanted to become a virologist (that would have been handy these days, huh?) but I didn’t want to spend the next 30 years in front of my life with my eye in a microscope. I had become very interested in cinema and in history, so at some point I thought I should look at one of those. But I had also taken creative writing at UBC too. I think they were happy to see me graduate because I was a professional student dilettante for a few years.

GW: What was the most exciting thing that happened for you intellectually speaking, at the Universal Biscuit Company?

AC: I know a lot of people went through school in a fairly pedestrian manner. But I treated it like a boxing match, and I often debated my professors vigorously, and arrived at some classes like a gunslinger that had just arrived in town. I wasn’t a know-it-all, or impudent. I was pleasant and well mannered enough, but I saw no reason to sit through classes and not get my money’s worth, and thought traditional opinions should be challenged. So I remember all manner of good discussions on History, Film, etc. when I was at UBC. Those were very stimulating. I very much enjoyed my time there. Making some film shorts while in school, as well as performing at the old legendary SUB Ballroom was a treat too.

GW: As per your involvement with music, what instrument did you play and did you have “training”?

AC: I had piano and violin lessons as a child. But they didn’t stick with me. When I began high school I think I wanted to be Stewart Copeland, but I couldn’t play drums very well! I was just a music fan. But I liked all sort of music. A meteor hit around 1987. I remember being in high school and seeing the Pogues’ video for Dirty Old Town, and I thought to myself, how do I get into this?! I wanted to get my hands on a mandolin, or some tin whistles so that music led me to get interested in a lot of that kind of stuff. From Billy Bragg to the Meth They Couldn’t Hang and Weddings, Parties, Anything, and I was fairly self taught. Punk Rock had been a revelation, and allowed you to get started pretty quickly. and I listened to everything from stuff like Killing Joke and Bad Religion, to Roland Kirk and Red Sovine. To this day it looks like four different people must have created my album collection. I played different instruments on each band I was in. Everything from Irish whistle and Mandolin with the Town Pants, to Omnicordm, musical saw, and Harmonica with Bocephus King. A little bit of percussion or guitar, melodica, accordion, you name it. I was the utility outfielder.

GW: How long was the arc of the music “career”? Maybe more to the point — is it over?

AC: I was an original member of the Celtic punk Poguesian The Real McKenzies [GW: he played bass, but after a year he was mainly a tin whistle player and left in 1997].[2] Then I spent a couple of years behind the scenes with Nomeansno, just on the road with them helping tour manage, and selling merch during the shows. That was a lot of fun, and like going back to “rock school” again! I played with Bocephus King, aka Jamie Perry, a fair bit around 2003, and did some studio recording stuff with the Be Good Tanyas and other bands around town. I fell in playing with The Town Pants (another popular celtic punk rock group), and toured all over the US, Canada, and Europe with them for a good dozen years too, but around 2012 when I wrote my first book, I kind of jumped off the back of the tour bus so to speak — mostly because I thought I couldn’t write these books on the road in hotel rooms.

So I never really left, but I enjoyed the writing as it was something you could do wholly on your own, and there were no sound checks. So I never really left. It was just a convenient move to take a bit of time off the road. But I still play a bit here in town with the Hard Rock Miners, and I’ve done some music for theatre and radio play productions in a project called Aaron Chapman and the Voodoo Radar Orchestra, which is not an orchestra but just one or two extra people. But we make enough racket as an orchestra — when needed! So, no, my music involvement continues.

GW: As a journalist in the realm of local history, who do you think is the best out there and why?

AC: The late Great Chuck Davis in a way still leads the pack — his was a whole lifetime dedicated to this genre, and yet there’s plenty of things he didn’t cover that are left for all his disciples to investigate and spread the word. I though Purvey and Belshaw’s Vancouver Noir was a mammoth work, and kicked off what I think will be looked back on as a renaissance period of Vancouver history writing — when a bunch of things started happening. John Atkin and Michael Kluckner remain stalwarts who were writing and painting long before this, too. But you have the release of the Herzog photo compilation books, the launch of the “Belshaw Gang” of writers with Vancouver Confidential, people like Tom Carter (another guy that grew up in Surrey and adored Vancouver and paints it so well), Jason Vanderhill (creator of the impressive Vancouver As It Was website) and especially Eve Lazarus’s books really kick into the next gear. Will Woods’ company “Forbidden Vancouver” starts to become a presence right on the streets. All of these projects are cross-pollinating one another. I suppose I’m in the middle of that, but I leave it to someone else to say where.

GW: Where do you see this going? In other words, are there other areas or themes that you’d like to explore?

AC: I don’t feel bound to simply write about Vancouver, and I have some other ideas brewing that would have more national or international scope. But right now there are just too many good stories about the city to tell, many of which most people have never heard. I’m born and raised here, so I notice how the city has changed before my very eyes. It’s my hometown. And to be perfectly honest I’ve always thought the stories here as just as good as can be found in London or New York. When you read and understand what’s happened here, it’s astounding. People say it’s a young history, and has no history — but its youth is what makes it so exciting. That the city has come together so quickly, and the changed have happened before your very eyes, and as much as Vancouver likes to paint itself as a modern, bright, cosmopolitan place, I can constantly see the dark heart of a port town that doesn’t care about the modern window dressing. Or at least I want to get it down in print before it totally disappears.

GW: In terms of the trio of books on local buildings or temples of entertainment, is that terroir at an end?

AC: Liquor, Lust, and the Law along with Vancouver After Dark and Live at the Commodore I suppose are a trilogy, but I just like to say that because it sounds like I always intended that from the beginning! There’s probably some more to tell about other venues or even room for a sequel for Vancouver After Dark. But I think the next thing I’m writing will have more to do with The Last Gang in Town than those Vancouver nightclub history books.

GW: Do you have any sadness about your own “golden age” of clubs and gigs as you allude to in your most recent book?

AC: Not at all. I was happy to be there for it. It was a wonderful time and I met some great people I still call friends today. I owe a great deal to the period. I met more people involved in film and literature from it, than had I just been involved in the local literature or history scene. It was so good, I knew at the time that I was living in what would be the good old days for my generation. But I was also well aware of the generation that had come before mine, and had really hit what might be considered a peak in the live music scene. Most of my friends were about ten years older than me so I heard the stories. I might have wished to have turned 19 before I did, so that I was legally allowed to get into clubs a couple of years earlier, because I missed some shows and bands that came to Vancouver that never managed to come back again, especially some British or Australian acts I was a fan of; but I was too busy enjoying the scene at the time to ever think it otherwise.

GW: In other words, do you see other times such as the sixties and seventies as one that you wished you’d really experienced, or does that fall into the kind of nostalgia trap of what-can-never-be?

AC: Not really. I mean, who wouldn’t want to take a time machine to any period. But the one thing that always happens with the “glory days” is they seem to change with every generation. Just about everybody who is middle aged thinks that they were present at the greatest time to be alive, and the time between they were 20 and 40. The generation before never had it so good, and the generation after just missed out. In reality, it changes and shifts. And the clubs in town have changed and shifted too, and moved to different neighbourhoods, which have been fuelled by the very changes in Vancouver itself over the last 30 years.

GW: Do you see a relationship between the rising cost of everything and its impediment to creativity and enjoyment by youth or younger people?

AC: No question. The costs of living are what really threaten the future of Vancouver. When I was a musician in the 1990s, three people could rent a four-bedroom house and leave one of the bedrooms for a music “jam room,” and get a band up on wheels. Nowadays people have to work a lot harder just to live here. That needs to change. It’s hard for everyone to kindle the imagination when you’ve got a constant eye on making sure you have the rent money.

GW: If so, outside of streaming an “entertainment” experience solo a la headphones and an iPad — where is this whole thing going besides into alienation and bypassing the communal experience?

AC: I view that as pretty temporary. People know the difference catching a song by their favourite performer as an informal on-line performance, and the live experience of seeing a performance. I take a historian’s view of it. Human interest in live performance goes back centuries all the way to the Greek plays. I certainly did not expect necessarily to see a pandemic in my lifetime, but, putting on my old virology hat again, I think we’ll see those days return sooner than we think. I think we’ll also see all our old habits — both good and bad — return even more quickly than we would have expected. It will take some time yet, and I can understand four or five months into this, with the way the all-Pandemic-all-the-time news is, many people live in fear. But I’ll tell you a nice piece of advice that a war correspondent gave me once that has served me well. “Never confuse what you’re afraid of with what can kill you.” The Influenza pandemic over 100 years ago killed millions more, but it passed, and the generation had the Roaring 20s to enjoy. The historian in me hopes we’ll have the same. I suppose we should just keep an eye on the stock market crash of 2029!

*

In 2015, this book’s predecessor, Live at the Commodore, was rewarded the Bill Duthie Booksellers’ Choice Award at the BC Book Prizes — ample proof of Chapman’s emerging abilities. With Vancouver After Dark, he may just have exhausted his comfortable terroir. For me, a more personal first-person account of the music and the reasons people paid to see the acts would have been the icing on this book’s cake. Chapman’s years of playing in bands, managing their schedules, and organizing their tours hasn’t yet been distilled and mixed into his writing; but if he ever did a book on his musical career, it might resemble Dave Bidini’s On A Cold Road: Tales of Adventure in Canadian Rock (1998), Tom Wilson’s Beautiful Scars: Steeltown Secrets, Mohawk Skywalkers and the Road Home (2017), or Grant Lawrence’s Dirty Windshields: The Best and the Worst of the Smugglers Tour Diaries (2017).

Aaron Chapman’s books find a ready and eager market among Vancouver readers. This is why Vancouver After Dark really matters. As a popular local historian, Chapman’s done yeoman service in creating almost singlehandedly a lively sub-genre of Vancouver history, and I hope there will be more in the pipeline from Chapman and the Arsenal Pulp team. Vancouver After Dark provides a sensitive and comprehensive account of the nightclubs that, between them, created a space to let us be ourselves.

*

Grahame Ware is a regular contributor to The Ormsby Review. He enjoys the intellectual and creative elbowroom afforded by the meta-review. For examples of this style, see his recent reviews of John Moore and Roy Miki. He has also contributed two Vancouver memoirs, My Private Chinatown and Grahame Ware’s Private Italy. He is the author of many ground-breaking articles in international horticultural journals and a member of the SFU-based Canadian Association of Independent Scholars. He sold his Fender amp and Gibson SG guitar to finance his return to SFU as a mature student in 1975. Grahame now lives on Gabriola Island where he cultivates his garden and solitude. However, he can’t wait for the new brew pub to be built at Silva Bay, where there will undoubtedly be an abundance of music and entertainment.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] An empirical study of this situation in Vancouver was recently conducted — indeed during the writing of Chapman’s book — by a consulting group called Sound Diplomacy. They conclude that, “Vancouver could benefit from greater partnership opportunities between the music industry and the booming film industry. Vancouver is the 3rd largest film and TV production centre in North America and the local music industry could further itself by making use of the proximity to such a successful and globally–recognised creative sector. The Province of BC increased support for the local music industry through Creative BC via the BC Music Fund, now called Amplify BC, which will see C $7.5 million invested in the music sector in 2019. Although Vancouver’s music scene is in some ways hidden in Canada compared to other major cities, the city has excellent potential and many opportunities through a number of portals…. In order for the Vancouver music industry to thrive, there must be affordable homes and work‑spaces, as well as good industry knowledge about processes, access and promotion. Interview responses showed clear concern about the ability of professional artists to sustain their lifestyles through their work. The rapid rise of housing and rental prices in Vancouver has increased the cost of living, making it particularly challenging to live on a salary between CAD $30,000 and CAD $50,000.” https://www.musicbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Vancouver-full-report-FINAL-19_07_2018.pdf [pp 45-6]

[2] “It all began sometime around 1992 in Vancouver when Scots-Canadian Paul McKenzie’s band split up and looking for something new he came up with the idea of combining the classic punk rock sound of his old band with the music of his Scots background and lo and behold, what we think of as modern, post-Pogues celtic-punk was born. Bagpipes had of course been used by all sorts of bands throughout rock history but a proper punk band with a piper was a first and The Real McKenzies showed the world that it was no novelty either.” For more, see London Celtic Punks.

2 comments on “#909 Twilight of the club scene”