#902 Demers’ therapeutic thriller

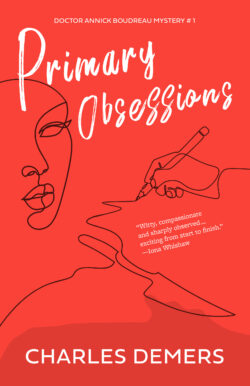

Primary Obsessions

by Charles Demers

Maderia Park: Douglas and McIntyre, 2020

$18.95 / 9781771622561

Reviewed by Paul Headrick

*

For authors working in the private detective genre, one of the challenges is to contrive a reason for the protagonist not to go to the police — not when important evidence turns up, not even when the bad guys have beaten the shit out of the detective. In the classic hard-boiled school, it often comes down to a combination of distrust of the police and loyalty to a client, some variation of the rich-but-sympathetic old guy living out his final days in the damp heat of his greenhouse, nursing his orchids along and trying to keep the family name out of the headlines. A clumsy handling of this problem often casts a pleasure-killing implausibility over a story, while an elegant solution can motivate an entire series of novels. Why doesn’t Walter Mosely’s Easy Rawlins go to the police? Because Easy is an African American man living in an African American neighbourhood in mid-century Los Angeles, with a notoriously racist police force. Only a self-destructive fool would go to the authorities in that situation.

For authors working in the private detective genre, one of the challenges is to contrive a reason for the protagonist not to go to the police — not when important evidence turns up, not even when the bad guys have beaten the shit out of the detective. In the classic hard-boiled school, it often comes down to a combination of distrust of the police and loyalty to a client, some variation of the rich-but-sympathetic old guy living out his final days in the damp heat of his greenhouse, nursing his orchids along and trying to keep the family name out of the headlines. A clumsy handling of this problem often casts a pleasure-killing implausibility over a story, while an elegant solution can motivate an entire series of novels. Why doesn’t Walter Mosely’s Easy Rawlins go to the police? Because Easy is an African American man living in an African American neighbourhood in mid-century Los Angeles, with a notoriously racist police force. Only a self-destructive fool would go to the authorities in that situation.

Charles Demers applies a twist to the client confidentiality device in Primary Obsession, and the skillfully turned manoeuvre does more than just establish plausibility. It’s central to the story. The amateur detective in this case is Dr. Annick Boudreau, a Vancouver psychologist who specializes in the treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. One of her clients, Sanjay, is arrested for murder, and Annick has information that would likely clear him. But she’s stuck. She can’t present her information without violating the ethical code of her profession.

Annick has good reason to feel responsible for Sanjay, so she sets out to find the killer. An important feature of the novel is its determination to confront the stigma of OCD, and as the mystery unfolds we learn quite a bit about the condition and its treatment with cognitive behavioural therapy. These psychological details add significantly to the story’s interest. In a sense, they add so much that it becomes a narrative problem.

The novel opens with a session between Annick and Sanjay, before the crime for which Sanjay will be falsely accused. The stakes are jacked up immediately. Sanjay is in desperate shape. His symptoms, including frighteningly violent thoughts that he can’t control, are overwhelming him. In a heartbreaking irony that’s true of much mental illness, the very nature of his condition makes it difficult for him to follow treatment. We care about his pain and also about Annick’s efforts to help him. She’s convincingly portrayed as an empathetic, committed and expert therapist.

The narrative problem is that the tension and interest created here are never matched by the investigation that follows. Annick encounters some nasty characters and threatening situations, but the evil-doers don’t become as vivid and entertaining as Annick’s colleagues in the clinic she works out of (especially Cedric, who is officially another CBT practitioner, but who seems most expert in a distinctly west-coast version of presentness). The problem of the unsolved crime fails to become as interesting or challenging as the problem posed by Sanjay’s OCD. A sub-plot involving illness in Annick’s family is handled quite well, but it feels as though it’s added in order to inject some of the tension that’s lacking in the main story. When the criminal case gets solved quite easily, we’re left unsatisfied that the issue that truly commands our attention, the psycho-therapeutic one that the novel in fact seems most invested in, isn’t explored further.

The novel is set in Vancouver, and for this Vancouver reader the descriptions of the city are sometimes a delight, capturing its beauty, its prosperity, and some of the cruel distortions that prosperity has produced. At other times those descriptions strike me as being overwritten, and overwriting in general is another problem limiting the novel’s success. Here’s the beginning of a chapter, about two-thirds of the way along in the novel, when the tension should be peaking:

There was a special alchemy which combined fear, optimism, determination and dread into insomnia, and on the nights when that particular psychic gumbo wreaked its attendant sleeplessness, Annick could also feel the effects of the day’s seven or eight coffees. Normally, ten hours of work and a liberal approach to both human sexuality and drowsy antihistamines were enough to neutralize the caffeine, but when alloyed with anxiety the coffees reared back up, frothing angry and empowered, shaking her from even the possibility of sleep.

Readers who enjoy this language will certainly like the novel better than I did. I found the style distracting and frustrating, draining away the tension. Annick is strung out over the case, and what demonstrates her stress is the simple fact that she can’t sleep. The details here don’t intensify the effect; they diminish it.

Dr. Annick Boudreau is a winning literary creation: she’s smart, funny, confident, and easy to cheer for. Demers plans at least one more novel with her as the central character. I hope the narrator will get out of Annick’s way a bit, relying more on her and what she says and does and less on hyped-up style. I hope as well that the complicated, high-stakes therapeutic challenges Annick faces will be more central to the plot. Psychology is important in lots of crime fiction, but there’s a potential here for a different kind of psychological thriller with a truly serious interest in illness and treatment.

*

Paul Headrick is the author of a novel, That Tune Clutches My Heart (Gaspereau Press, 2008; finalist for the BC Book Prize for Fiction), and a collection of short stories, The Doctrine of Affections (Freehand Books, 2010; finalist for the Alberta Book Award for Trade Fiction). He has also published a textbook, A Method for Writing Essays about Literature (Thomas Nelson, 2009; 3rd edition 2016). Paul has an M.A. in Creative Writing and a Ph.D. in English Literature. He taught creative writing for many years at Langara College and gave workshops at writers’ festivals from Denman Island to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. He is a mentor for the graduate fiction workshop in The Writer’s Studio at SFU. Editor’s note: Paul Headrick has also reviewed books by Rhea Tregebov, Hazel Plante, Anakana Schofield, Deni Ellis Béchard, Linda Rogers, Kathy Page (Dear Evelyn), Kathy Page (The Two of Us), and Karen Charleson for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#902 Demers’ therapeutic thriller”