#883 Everyone’s Thomas Merton

Superabundantly Alive; Thomas Merton’s Dance with the Feminine

by Susan McCaslin and J.S. Porter

Kelowna: Wood Lake Books, 2018

$19.96 / 9781773430355

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

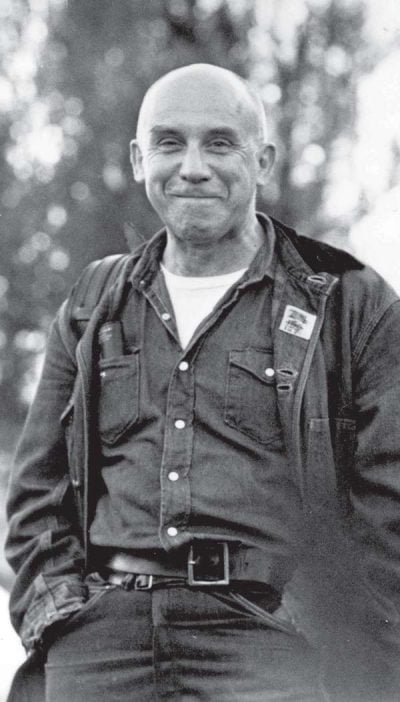

Does everyone have their own Thomas Merton? The quiet charisma of the mid-20th-century hermit/ Christian apologist / writer / activist speaks directly and personally to each of his readers.

Does everyone have their own Thomas Merton? The quiet charisma of the mid-20th-century hermit/ Christian apologist / writer / activist speaks directly and personally to each of his readers.

Reviewing Mary Gordon’s On Thomas Merton, also published in 2018, Benjamin D. Crace wrote: “Gordon’s text is a curated commentary, a conversation between writer and reader about another (absent) writer. And while reading On Thomas Merton puts one in the room where the conversation is happening, it is hard to know just how to respond. This is not Thomas Merton; this is Gordon’s Merton…”

Saints and mystics are vulnerable to this sort of appropriation. Years ago I wrote an article about St. Catherine of Sienna as a feminist. It was published in Kinesis, the journal of the Vancouver Status of Women. That was my St. Catherine, not necessarily recognisable by Catholic scholars. As soon as I permitted myself to view the Thomas Merton of this book as McCaslin and Porter’s Thomas Merton, I stopped searching his work for validation of their version. Susan McCaslin is an accomplished poet, familiar with gods and goddesses, Christian and pagan. She is also a scholar, partnering in this book with fellow poet and Merton specialist J.S. Porter. If they choose to portray Thomas Merton dancing with Sophia, I should relax and enjoy the spectacle, especially as they claim he danced like Zorba the Greek.

Merton differs from others in his generation of direct-activist American Catholic clergy: notably Daniel and Philip Berrigan, Elizabeth McAlister, and the group around the Plowshares Movement (including three nuns, Sisters Ardeth Platte, Carol Gilbert, and Jacqueline Hudson who in 2001 broke into a missile silo near Seattle, armed with household hammers, rosaries, and baby bottles of their own blood, and were sent to prison for endangering the security of the United States of America). These were “secular” clergy, out and about in the world, while Merton was a Trappist monk, one of the “regular” [i.e. committed to a specific strict “rule” (regula) of life] clergy, a difference which added a more conflicted dimension to his activism.

I have a set of CDs on which Merton is teaching about contemplation. His voice is that of someone who grew up in New York before spending many years in Kentucky, an American voice in the tones of Gary Cooper or James Stewart, or Ed Harris as Fr Frank Shore in The Third Miracle, or a professor of American literature who led a memorable seminar on William Faulkner at UBC in the 1960s. In these interchanges with his students, as in his writings, Merton brings matter-of-fact inflections to transcendent topics.

The authors want Merton to dance with two conflicting “feminines.” They want him to be a devotee of Hagia Sophia, Holy Wisdom, a personification of “the sacred feminine” or “the feminine divine.” Indeed Merton did contemplate Sophia in his prose and in a prose poem which they reproduce in order to analyse, but, as far as I can tell She was part of his contemplation, not its central kernel. Here I betray my personal difficulty with Hagia Sophia, an ancient thread within the intricate web of Christian spirituality. Unlike Merton’s works, Superabundantly Alive pays little attention to the human person of Jesus of Nazareth. The incarnation as male makes sense in the historical and geographical context. I can’t — and don’t want to — turn a real person, male or female, into an abstract figure of Wisdom, and I worry when abstract Wisdom begins to look like the goddess Athena of classical Greece.

Then there is the other “feminist” theory which imagines Jesus in a romantic relationship with Mary Magdalen. Although the authors do not overtly make the connection, Nikos Kazantzakis, the author of Zorba the Greek, also wrote The Last Temptation of Christ. Thomas Merton walks, or dances, right into that narrative. Sometime after he had already written about Hagia Sophia, he apparently lapsed into a love affair with a nurse to whom he refers as “M.” McCaslin writes a chapter of imagined “love letters for Tom and Margie,” and she and Porter place her central to their argument. Merton did not make a secret of the early flings which occurred before his conversion. (St. Augustine may serve as precedent.) If those flings did not attest to his “feminism,” it is not clear that this later affair did either.

I am confused by McCaslin’s confusion at Merton’s decision to end the liaison: “Despite not being able to commit himself to quotidian life with Margie (for complex reasons we might never entangle), I see his relationship with her not as a lapse, but as an emotional and spiritual breakthrough.” Surely those “complex reasons” are all about his previous commitment when he entered the monastery as recounted in his autobiography The Seven Story Mountain: “So Brother Matthew locked the gate behind me and I was enclosed in the walls of my new freedom.” Merton’s relationship with M. may have renewed his recognition of the meaning and implications of that freedom, but I don’t see it as a “breakthrough.” He returned to his chosen life, and she got on with hers. If this is not the story McCaslin wants, that is her problem. Porter too, because he enjoys his own children, imagines Merton’s regret at missing out on fatherhood, but admits “I wasn’t sure if I was talking about Merton or about myself.” I think, definitely the latter.

The feminine with whom the authors want Merton to dance is both sex fantasy and pantheistic spirit, and for this reader an unnecessarily obscure object of desire.

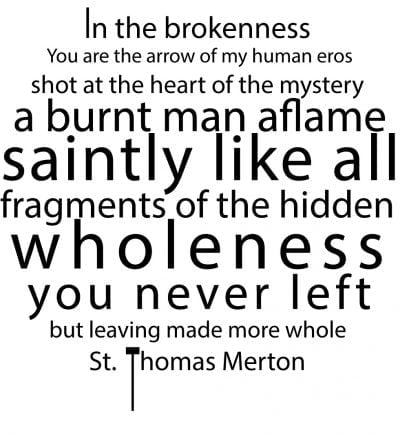

The book’s title is borrowed from “Harpo’s Progress: Notes toward an Understanding of Merton’s Ways” by his college mate and close friend the hermit poet Robert Lax:

[Merton’s] own poems and fables, dramas and songs were works of the spirit, praise of the Lord, particularly of his mercy: sometimes directly, sometimes by inference; sometimes simply by the fact of their being. Ever creative, seldom didactic, they were always superabundantly alive.

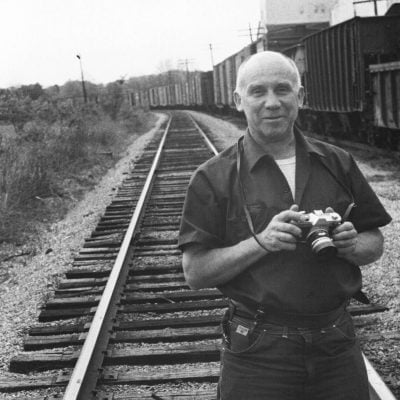

Lax pictures Merton dancing, and not only with the feminine: “The drawings, the photos? Filled with that same joy (the joy of David dancing before the Ark of the Covenant): a cause for rejoicing.”

In separate sections, McCaslin and Porter each trace their own engagements with Merton’s life and work. Then they collaborate to exchange ideas of “The Divine and Embodied Feminine.” In the chapter “Embodying Sophia,” McCaslin gives an in-depth reading of Merton’s “Hagia Sophia,” in which he wrote: “This mysterious Unity and Integrity is Wisdom, the Mother of all, Natura naturans.” She inquires in what ways Merton’s Sophia “anticipates feminist concerns.”

McCaslin offers a series of poems “A Grotto of Sophia Ikons” with graphics designed by her niece Afton Schindel, in which they imagine what “saints” might figure in Merton’s hagiography, beginning with his mother, “St.” Ruth Jenkins Merton, and including among others “St.” Robert Lax, St Therese de Lisieux, “St.” Joan Baez, and “St.” Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama.

The section “Love and Solitude; a Cache of Love Letters for Tom and Margie,” which I continue to find presumptuous, is followed by “Pivoting toward Peace,” an interesting juxtaposition of Merton’s “transformative poetry” with that of the American poet Denise Levertov, their shared beliefs and political activism. That I find the Levertov chapter the most meaningful in the book again might say more about me than about the writers involved.

In her concluding chapter, McCaslin adopts Merton as patron of her environmental activism: “Balancing the lyrical and exploratory voice with a poetics of political engagement was challenging. Merton’s words in Contemplation in a World of Action have served as a guide.” She quotes Merton: “In the contemplative life, action exists for the sake of contemplation and vice versa. The openness of the contemplative is justified insofar as it enables [her] to be a better contemplative and to share with others the fruit of [her] contemplation.” Only, that is not quite what Merton wrote. As the square brackets indicate, he used the masculine pronouns him and his, which in the antediluvian 1960s when the book was written we still understood to include the feminine.

Appreciating that Christianity can embrace differing styles of spirituality, I am grateful to McCaslin and Porter for motivating me to return to Merton’s own writings, not to validate their theories, but to re-examine my Thomas Merton and find neither he or I quite the same as at our previous encounter.

Editor’s note: see here for an interview with Susan McCaslin on writers radio.ca

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications, including the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website. For The Ormsby Review she has reviewed books by Ian Hampton, Carys Cragg, Yvonne Blomer, Robert Amos, Joe Rosenblatt, Eileen Curteis, Naomi Wakan, among others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#883 Everyone’s Thomas Merton”