#851 Hockey fighting man

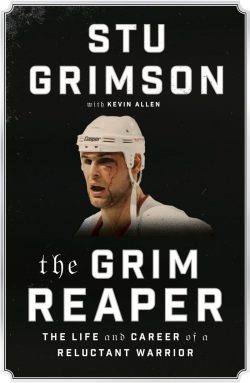

The Grim Reaper: The Life and Career of a Reluctant Warrior

by Stu Grimson with Kevin Allen

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Viking), 2019

$32.95 / 9780735237247

Reviewed by Timothy Lewis

*

Stu Grimson played 729 games in the National Hockey League, recording 17 goals and 22 assists. Those are not scoring statistics normally associated with a 14-year professional hockey career, but Stu Grimson’s athletic longevity owed far more to the 211 major penalties for fighting he racked up during his time in the NHL (p. 1). Yet in his new book, The Grim Reaper: The Life and Career of a Reluctant Warrior (with Kevin Allen), Grimson reveals that the role of hockey enforcer was one he was slow to accept.

Stu Grimson played 729 games in the National Hockey League, recording 17 goals and 22 assists. Those are not scoring statistics normally associated with a 14-year professional hockey career, but Stu Grimson’s athletic longevity owed far more to the 211 major penalties for fighting he racked up during his time in the NHL (p. 1). Yet in his new book, The Grim Reaper: The Life and Career of a Reluctant Warrior (with Kevin Allen), Grimson reveals that the role of hockey enforcer was one he was slow to accept.

Like so many hockey tough guys, fear and anxiety plagued him before virtually all of his fights, and the book provides valuable personal insight on a time in NHL history, from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, when the violent culture of the hockey enforcer was at its peak. Over time, Grimson came to see value in defending and protecting his teammates, and he now seems at peace with the violent role he played. However, he downplays the significant number of deaths and serious health consequences that the tough guys of his era have since experienced, a notable exception in a book that otherwise deals frankly with the significant challenges that came with being an NHL enforcer, both on and off the ice, in the years approaching the 21st century.

In his introduction to The Grim Reaper Hockey Hall of Famer and former Stu Grimson teammate Paul Kariya provides the following tribute: “No tough guy understood his role more than Stu…. anyone who ever played with [him] understands that we owe him a debt of gratitude for how he helped our teams. Nobody looked after teammates better than Stu did” (p. xiii). But the role of hockey tough guy was not a natural fit for Grimson. He left his first pro training camp with the Calgary Flames specifically because he did not want to become a career fighter. Neither the limited playing time assigned to tough guys, nor the humiliation that followed a public beating in front of thousands of fans, were appealing to Grimson.

However, his love for hockey was reignited shortly thereafter when he joined the University of Manitoba Bisons for a two-year stint in a league where fighting was banned. He flourished in the larger, more diverse role he was given, and Grimson’s time with the Bisons renewed Calgary’s interest in signing him to a professional contract. Yet despite his development as a more all around player, the role the Flames had in mind for Grimson, who stood 6’6 and weighed close to 250 pounds, remained clear. If Stu Grimson wanted to climb the pro hockey ladder, he would have to do it with his fists. He continued to struggle with that idea, but acts of violence were not entirely foreign to the self-described “reluctant warrior.”

The adopted son of career RCMP officer Stan Grimson and his wife Em, Stu admits to regularly engaging in extreme behaviours, including occasional acts of violence, as a teen; the goal being to garner attention and earn fast friends as the family moved from town to town. Indeed, Grimson first came on the hockey radar in a serious way when a major junior scout happened to drive past Stu and a few friends engaged in a street brawl in Kamloops, British Columbia. Grimson’s impressive showing in that fight earned him an invitation to the Regina Pats training camp, and eventually paved his way to the NHL. Even Grimson’s time at the University of Manitoba was tainted by an on-ice confrontation with an opposing player that spilled over into an under-the-stands beating that earned Grimson a lengthy suspension and a year of probation from the courts. Thus the “reluctant warrior” did have a violent side to him as a young man.

That being said, Grimson remained uneasy with being pigeonholed as just a tough guy, especially when the battles felt artificial. “I’m sure I wasn’t the first guy who had trouble making peace with the role . . . . I enjoyed protecting my teammates. It felt noble and right. What I didn’t enjoy was the feeling that I was expected to fight. . . . . having to manufacture adrenaline and intensity before a fight was difficult. I couldn’t seem to dial up enough anger in those battles. I could do the job, but I wasn’t comfortable doing it” (p. 24). Grimson grew more confident as a hockey tough guy once he received ample ice time in Calgary’s farm system. However, the real test as to whether Stu Grimson had what it took to be a top-notch NHL enforcer came in January 1990, when the Flames recalled him for his second and third games in the NHL as Calgary prepared to once again meet their archrivals: the Edmonton Oilers. For Grimson, that meant the nerve-wracking prospect of battling with the Oilers’ super tough guy Dave Brown:

. . . for me, everything was on the line. Everything I had worked for. . . . . I was so anxious in the hours and minutes leading up to that fight I couldn’t produce the saliva to spit. . . . The spotlight was on me. Every Flames fan was watching. Every Flames fan cared. . . . . I knew that the path to an NHL career ran right through Dave Brown and this was my moment (p. 79).

Still an unknown commodity at the NHL level, Grimson scored a decisive victory over Brown in the first game in Edmonton. His Flames’ teammates were impressed. “When I skated back to the bench after serving my five minute major, Theo Fleury was the first to put some perspective on what I had just done. ‘Do you have the number of a real estate agent in Calgary?” he asked. You’re going to be with us for a while” (p. 80). But as happy as he was with the outcome of their first encounter, Grimson knew all too well that Dave Brown would be looking to exact serious revenge in the next game in Calgary, just a few days later, and that he did.

When the two combatants squared off in the return engagement, Brown hammered Grimson with a devastating series of left hands that resulted in “a two-and-a-half-hour emergency reconstructive surgery to repair an orbital bone that had been fractured in two places” (p. 82). The horrific beat down inflicted by Dave Brown was, in many respects, the fulfillment of Stu Grimson’s worst hockey nightmare. But, ironically, rather than putting an end to his career as an NHL enforcer, the traumatic loss to Brown convinced Grimson that he was on the right path. “Getting my orbital bone crushed by Brown in 1990 was probably one of the best things that ever happened to me. It was certainly the turning point in my professional career. . . . . My thinking was that the loss to Brown, and the subsequent surgery, were as bad as it gets in that line of work. . . . . In my mind, I had nothing else to fear” (p. 84). Moreover, Grimson informs his readers that there “is nothing more rewarding or liberating in life than facing down your greatest fears and moving past them. . . . . if this book is about one thing, it’s about the freedom and peace you find on the other side of fear, both on and off the ice” (p. 86).

From that point on, most of The Grim Reaper is devoted to the ups and downs Grimson experienced as an NHL tough guy who played for seven different franchises, in eight different cities. Along the way, he provides engaging details on his regular confrontations with well-known enforcers including Bob Probert, Joey Kocur, and Georges Larocque, sheds light on the somewhat nebulous ‘Code’ of honour hockey’s tough guys roughly adhered to out of respect for their fellow ‘warriors’, and offers personal insight on the unique characters of iconic coaches Mike Keenan and Scotty Bowman. Moving to his off-ice career, Grimson gives the reader a behind-the-scenes view of his controversial time as a lawyer for the National Hockey League Players’ Association during an era when that organization was going through considerable turmoil.

Grimson presents as open and honest throughout, but The Grim Reaper is at its best when the author delves into the unique mentality that was required of those who took on the role of NHL enforcer in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, an era when the men who served in that capacity were both larger and more dangerous than ever before.

Despite the small number of minutes they generally played in any one game, Grimson argues forcefully that the leading tough guys of his era made crucial contributions to the success of their teams and teammates. Consequently, he never makes use of the derogatory label ‘goon’ when describing them; rather, he paints a picture of men who were the very heart and soul of their teams. “No one is more invested in the team than the tough guy. He’s the player who puts it all on the line every time he drops his gloves. . . . Two fierce combatants . . . throwing bare-fisted punches with enough force behind them to crush human bone is a frightening proposition. . . . . But for the tough guy, raising the level of his team’s play and turning momentum [with a successful fight] is his primary responsibility (p. 165).

To succeed in that daunting role, however, often required the NHL’s best enforcers, Stu Grimson among them, to drastically alter their generally mild-mannered off-ice personalities. “You’ve got to push yourself to play on the razor’s edge of adrenaline. . . . . People used to say they were surprised by how affable I was in public. But when I laced up the skates, the wires would touch and I would operate at a higher voltage. I became a very different person” (p. 165). However, the physical and emotional drain of preparing for and engaging in regular on-ice battles over an 80+ game schedule, especially for those who did so for a decade or more, was severe. While his imposing physical size and gruff on-ice demeanour projected the fearlessness of a trained killer, Grimson reveals that he, like the other tough guys of his era, felt tremendous anxiety and pressure as he battled nightly to control his emotions and preserve his job. He argues that hockey enforcers “face down a level of fear that is probably far beyond anything athletes face in any other sport. A boxer or a mixed martial arts fighter may know well the sense of dread that hangs over you before an upcoming fight. But the boxer goes through that process just once or twice a year . . . For an NHL heavyweight, you go through the preparation daily. . . . . we owe it to these guys as human beings to attempt to understand what they endured. If you stare down fear like that night after night, year after year, it takes a toll” (pp. 181-182).

No surprise, then, that virtually every long-term NHL enforcer looked for coping mechanisms to keep the physical and emotional pain they experienced in check. For most, drugs and alcohol became the strategy of choice with negative, by times deadly, results. Grimson drank rather heavily during his time in junior hockey, but he eventually found a healthier means of coping with the stresses associated with his chosen profession. Inspired by the example set by his in-laws from his first marriage, Stu Grimson embraced Christianity in a far more committed manner. He found that his reinvigorated faith gave him greater mental peace, and he came to see his role as the protector of his teammates in almost spiritual terms. Consequently, the daily strains that accompanied his unusual occupation became more manageable.

That is not to say that Grimson’s faith allowed him to magically skate through his many years as a hockey tough guy unscathed; far from it. He was forced to retire before he planned following a major concussion he received from a fight with Georges Larocque in December 2001, and the serious post-concussion symptoms remained with him for some two years afterward. Moreover, the end of Grimson’s 26-year first marriage seems to have come, at least in part, by the transient lifestyle he, like other enforcers, led as he was traded or moved from team to team. But perhaps because of his considerable post-hockey success – he is a practicing lawyer as well as a television analyst with the NHL Network, and is now happily remarried – he does not dwell on the personal costs associated with his violent on-ice career. “You will never hear me complain about the job I had” (p. 182). Even when he discusses the early deaths of several of his NHL heavyweight counterparts, Grimson treads lightly. “I’m not going to list all the enforcers who died premature deaths, some by their own hands. That list is too long, and too disturbing” (p. 180). Thus if there is one portion of The Grim Reaper where Grimson becomes something of a ‘reluctant writer’ it is when he touches, however briefly, on the deadly consequences too many have faced as a result of their years of hockey fighting.

Despite his stated desire not to list all the hockey enforcers whose lives ended far too soon, Grimson does, in fact, refer to a number of those men: John Kordic, Bob Probert, Wade Belak, Mark Rypien, Derek Boogaard, Steve Montador and Jeff Parker. Significantly, many of those individuals have since been found to have suffered from the devastating brain disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a condition linked to repeated head trauma. Grimson expresses empathy for those who died. He also admits to having some concerns about his future health, and regrets not reporting the many concussions he almost certainly experienced earlier in his career, but chose to ignore due to his desire to continue playing. (pp. 259-261).

However, unlike many of the families of the hockey tough guys who have passed away, and the ex-enforcers who continue to battle significant mental and physical hardship arising from their playing careers, Grimson is reluctant to draw a straight line between hockey fighting, CTE, and the deaths that have resulted. “The connection seems obvious for some: fighting leads to concussions, concussions lead to CTE, and CTE leads to depression and dementia. But I am not rushing to make that connection until the opinion of the medical community is somewhat more settled. And besides, each of these men died from causes that were unique to them. And the varied causes of death may or may not be linked to the roles we all held formerly” (pp. 260-261). Likewise, Grimson firmly believes that neither the NHL, nor its leadership, should be held to account for promoting the culture of fighting that has seemingly contributed to the severe medical consequences so many former hockey enforcers now deal with. “Do I want the NHL to assist former players suffering from long-term medical issues? Yes, I do. Do I support the efforts to make the game safer? Of course I do. But am I willing to say the NHL promoted a culture of violence and hate and that no one should be playing under the current conditions? No, I am not. The truth is that I knew, and I’m guessing others did as well, that there was potential risk in doing what I did for a living. Common sense told us that” (p. 262). Grimson then goes on to assert that: . . . . “I don’t believe the medical community knew enough about this area thirty years ago to provide any of us with definitive answers. But even if I had access to research that showed a potential for long-term health problems as a result of head trauma, I still would have played. . . . . Even now, given the scientific advances in this area, it’s still a question of personal liberty in my opinion” (p. 262).

Grimson clearly demonstrates his skills as a lawyer to state the case that the NHL bears no significant blame for the deaths, or long-term health issues, so common amongst the hockey tough guys of his era. Whether that line of argument owes more to lingering pride in his own career, which provided millions of dollars of income for him and his family, or his current work as an analyst for the NHL Network at a time when the league continues to deny any direct responsibility for those who have suffered ill effects due to hockey violence under its auspices, is unclear. Either way, Grimson pulls his punches on this topic, something that is otherwise rare in the book.

Stu Grimson clearly prepared for the writing of The Grim Reaper with the same all-in mindset, good humour, and honest approach he took throughout his hockey career, and the results are satisfying for the reader. He offers frank insight on the anxiety, stress and fear that the hockey enforcers of his era dealt with on an almost daily basis, and assertively defends those players’ contributions to the sport both on and off the ice. That he cannot, in the end, fully turn his back on the violent role he and others played in the game, despite the growing body of medical evidence that suggests that the NHL’s tough guys paid far too high a price for their efforts, is also understandable. Some may question why Grimson, a loyal protector of his teammates throughout his hockey career, has chosen not to fight harder for those of his former colleagues who continue to battle the NHL off the ice. But, all in all, Stu Grimson, the reluctant warrior, produces a rewarding read.

*

Timothy Lewis is Professor and Chair of History at Vancouver Island University in Nanaimo. Among the courses he teaches are several focused on the emergence and development of professional sports in Canada, and the place of hockey within Canadian identity. His research work is focused on the history of 19th and 20th-century New Brunswick, portions of which have been published in two articles in Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region. His previous sports book reviews for The Ormsby Review include Jared Beasley, In Search of Al Howie (no. 791, April 5, 2020); Jeremy Allingham, Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey (no. 718, January 9, 2020); Kate Bird, Magic Moments in BC Sports: A Century in Photos (no. 695, December 16, 2019); and Michael G. Varga and Roxanne Davies, Inside View: The Eye Behind the Lens (no. 826, May 19, 2020).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster