#848 The ballad of Ginger Goodwin

Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin

by Susan Mayse

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2020; first published by Harbour, 1990

$28.95 / 9781550170184

Reviewed by Dan Hinman-Smith

*

We’re all working men here,

And we drink Lucky Beer,

Do we hold a grudge?

You bet.

— Gordon Carter, “The Day They Shot Ginger Down”

“Private Goodwin, serial number 270432, was the name on his unclaimed order to report for military service,” wrote Susan Mayse in introducing the subject of her 1990 biography. “. . . Albert Goodwin was the name on his union card. He was Brother Goodwin to fellow executives of the British Columbia Federation of Labour, and to other Marxian socialists he was Comrade Goodwin. He signed his letters ‘Yours in Revolt,’ and later ‘Fraternally Yours for Socialism.’ . . . His friends called him Ginger.”[1]

Mayse’s Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin has now been re-published by Harbour three decades later. It follows the struggles of the young radical, union organizer, and conscientious objector from his entry into the coal mines of Yorkshire as a teenager, across the Atlantic to Cape Breton and then to the mines and smelters of British Columbia, before ending with his death at the hands of the Dominion Police in the woods behind Comox Lake. Along the way, we see Goodwin as a participant in the bitter 1909-1910 United Mine Workers of America strike at Glace Bay, Nova Scotia; as a UMWA Cumberland delegate during the Vancouver Island coal strike of 1912-1914; as a provincial candidate for the Socialist Party in the Ymir riding in the 1916 election; and as the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers lead organizer for the 1917 wartime strike against the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company in Trail.

Outspoken not only in his demands for an eight-hour day but in his critique of the war, a physically compromised Goodwin was reclassified from Category D status (temporarily unfit) to Category A (fit to fight) just eleven days after the start of the Trail strike. Defying conscription, he sought refuge with a small group of fellow war resisters. Subject to a manhunt, he was shot and killed by special constable Dan Campbell on July 27, 1918.

Ginger: The Life and Legend of Albert Goodwin is not only an imaginative and well-written work of creative non-fiction, but an important contribution to the telling of B.C. history. Of particular note here are the thirty-eight interviews conducted by Mayse with thirty-four different individuals during the 1980s that contribute to the book’s distinctive cadence. Mayse then combined the materials from these sources with information and intonations garnered from an additional two dozen other interviews recorded over twenty years by several other local researchers.[2]

This ambitious foray into oral history is one of the book’s most distinctive features and helps Mayse to draw sharp portraits of such characters as the Cumberland union activist Alex Rowan, whose promising long-distance running career was cut short by a 1910 mining accident; the Minto Norwegian-American socialist Ole Oleson; and the Cumberland World War I veteran Robert Rushford, who returned home in 1915 to a hero’s welcome but also to the death of his baby daughter Ypres, and then later was reluctantly drawn into the search for Goodwin and other draft evaders as Cumberland’s chief constable.[3] Mayse not only shared her research with Roger Stonebanks as he worked on his own biography of Ginger Goodwin, but also donated one metre of subject files, eighty-six photographs, and thirty-one sound cassettes to Special Collections and Archives at UBC as a resource for future historians.[4]

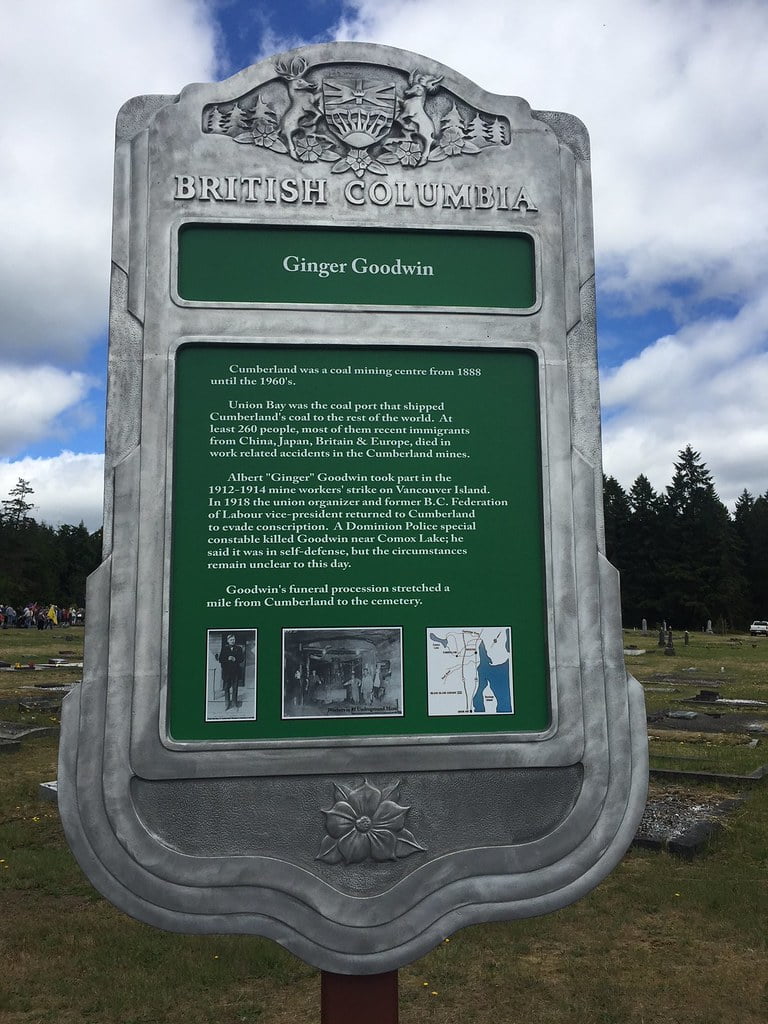

“The story of Ginger Goodwin has always been plural and ambiguous: one figure’s story with many variants,” argued Jesse Birch in a 2010 essay that used Mayse’s book as a core resource. “In many ways his story could be seen as a point of contestation between official narratives and those that circulate by other means.”[5] Not surprisingly, debate about the meaning and memory of Goodwin stretches back to his own era. “He is very poor material for martyrdom,” suggested a dismissive editorial in the Vancouver Sun on August 2, 1918. “His name does not belong in the calendar of saints. His conduct was an evil example, which brave men or patriotic men cannot condone. Let his friends grieve if they will, but let all other good citizens cease to mention him henceforth.”[6] However, that same day some 5,500 Vancouver workers walked off the job at the urging of the Trades and Labour Council and the Metal Trades Council “as a protest against the shooting of Brother A. Goodwin,” an action often identified as Canada’s first general strike.[7] And in Cumberland, miners put down their tools to participate in a mile-long funeral procession. No ministers but rather three individuals associated with the Socialist Party of Canada – including future CCF MLA William Pritchard and miner and Goodwin mentor Joe Naylor – officiated at the graveside.

“Not in the Catholic section, not in the Protestant section, but away in the unpopulated back quarter near the overhanging fir trees, the people of Cumberland buried Ginger Goodwin,” wrote Mayse of the funeral.[8] She acknowledged that by 1990 Ginger Goodwin had long since become a larger-than-life figure. “Vancouver Island has only a handful of mythmakers in recorded and remembered history,” she suggested. “ . . . These are not icons of official history but people like boulders in history’s current, around whom events have had to flow and change direction. They make up the matter and spirit of Vancouver Island, the fact and essence, the stuff of legend. Among them belongs Ginger Goodwin.”[9] She noted that the story of Ginger Goodwin had already been portrayed through various media: songs, books of different types, poems, plays, paintings, sculptures, plaques, and museum exhibits. “We can reasonably look forward to musical theatre, films and other artistic interpretations,” she predicted.[10]

Indeed, Mayse herself experimented with telling the Ginger Goodwin story through different forms. She initiated her series of interviews with retired Nanaimo and Cumberland miners and their wives as research for a planned novel about the Vancouver Island coal strike of 1912-14.[11] “In asides and fragments [the interviewees] told me about a ‘worker’s friend’ who laboured to better their lot, and paid with his life,” she remembered. “I found that I couldn’t talk about coal mining in Cumberland without talking about Ginger Goodwin.”[12] Although her original plans were scaled back somewhat, Mayse did write the drama “Deep Seams” for CBC Morningside Radio in 1986. This was then followed by her commission for “A Worker’s Friend: The Shooting of Ginger Goodwin” as a May 1989 CBC “Ideas” episode.[13] She continued after the 1990 biography with a 1995 play, “Yours in Revolt,” which revolved around the friendship and union activism of Goodwin and Joe Naylor.[14] She even collaborated with producer Peter Walsh and director Vilmos Sigmond on a planned $8 million feature film, writing the first draft of a script, though that Goodwin project did not come to fruition.[15]

That Mayse’s chosen subject had been transformed into a myth imposed upon her the perceived responsibility to uncover the real history. “As this story is too consequential for repressive falsehoods, it is too consequential for flattering iconography,” she declared in the book’s introduction. “Instead it demands the difficult task of going back to uncover – beneath the passions and confusions and lies – something like the truth.”[16] By that standard, Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin falls somewhat short. In a harsh but thoughtful contemporary review, the Simon Fraser University labour historian Mark Leier skewered Mayse for various errors of fact, misunderstandings, and questionable interpretations. He was particularly scornful of the amount of speculation that Mayse engaged in about Ginger Goodwin’s death. “Goodwin had a . . . profound critique of our society,” concluded Leier, “and it is a pity that his biographer has diminished his vision by turning his story into a whodunit.”[17]

Leier has expressed repeated frustration that an emphasis upon the precise details of Goodwin’s death too often sidelines an analysis of his ideology.[18] “The conspiracy theory . . . blames not the system but a few villains,” he wrote in 2007. “Conspiracy theory . . . is essentially a liberal theory that prefers not to challenge the social order but to prop it up by deflecting attention away from the real nature of capitalism.”[19] And, indeed, though Mayse does describe Ginger Goodwin as a radical, her book needed a much more coherent discussion of the early twentieth-century labour movement and of Goodwin’s own thought. “This is no sentimental movement, and the masters can howl,” Goodwin announced in August 1913; “we do not hide our intentions, for we are what they have made us – the dispossessed class that is out to overthrow them.”[20]

The Mayse book was intended for a popular audience. That does not excuse her, however, for not exercising more rigour, nor for not familiarizing herself with the relevant academic literature. There are important ways in which her study has been superseded by former Victoria Times-Colonist journalist Roger Stonebanks’s Fighting for Dignity: The Ginger Goodwin Story (Edmonton: Canadian Committee on Labour History, 2004), and it is recommended that the two books be read side-by-side to best appreciate Ginger Goodwin as both folk image and historical figure. Stonebanks is meticulous in his attention to detail and combines this with grounded analysis. He gently debunks some of the folk legends that make their way into Mayse’s biography, such as the claim that miner Arthur Boothman had played soccer for Tottenham Hotspur; that Joe Naylor had been bespattered as a youth on an English highway by a coach that included the future king of England; and that Ginger Goodwin returned from his hiding place in the mountains of Comox Lake in 1918 to attend Saturday night dances in Cumberland.[21] Stonebanks also resituates the photograph of Goodwin that plays such a prominent role in the prelude of Mayse’s account from 1911 to 1916 or 1917.[22]

Mayse’s connections with the myth of Ginger Goodwin were forged not just in the parlours of elderly Vancouver Island miners, but through her familial past as well. Her grandfather Amos Mayse worked in the coal mines of Ginger Goodwin’s Yorkshire before becoming a Baptist minister and an emigrant to Canada before World War I.[23] Her father Arthur (Art) was, if not of the historical stature of Goodwin, still somewhat of a legendary B.C. character himself who spent much of his writing career as a labour, politics, and features reporter for the Vancouver Sun and the Victoria Daily Times. He and his fellow-writer-wife Win spent their last twenty years living between Oyster Bay and Campbell River in a beachside former logging camp float-house that had been owned by the bounty hunter and game warden Cecil “Cougar” Smith.[24] “He knew Cowichan shamans, Sointula pukka fighters, tame apes from the A-frame camps, Chinese labourers and unrepentant Wobblies,” eulogized his son-in-law Stephen Hume in 1992. “More than anything, he knew and loved the country. He lived it, breathed it, fished it and sometimes despaired at what was being done to it in the ignorant clamour called progress.”[25]

Arthur Mayse first heard about Ginger Goodwin as a young man in 1934.[26] A 1981 Vancouver Province article pictures Arthur Mayse visiting the grave of Ginger Goodwin.[27] “My father says that some voices speak beyond death and beyond time,” noted Susan Mayse in attempting to explain the pull of the Goodwin story on her imagination.[28]

Ginger Goodwin still lay in an unmarked grave when he first spoke to Arthur Mayse from beyond death. When the coal miners of Cumberland finally gained union recognition in the mid-1930s, the grave received a headstone. His fellow 1912 striker Vincent Picketti commemorated Goodwin with an inscription that honoured the pacifist union organizer as one fallen in war: “Lest we forget, Ginger Goodwin, shot July 26th 1918, a worker’s friend.”[29] The date was off by one day, a recurring error in the Ginger Goodwin story. The hammer and sickle that Picketti placed at the top of the stone reflected the Communist affiliations of the Canadian Labour Defence League and the Mine Workers Union of Canada, the organizations that commissioned the monument before the miners’ final 1937 absorption into the United Mine Workers of America.[30] The pluralities and ambiguities of the Ginger Goodwin story reflect not just the conflict between labour and capital but also the tensions within the labour movement.

In recent decades, the grave has become the focal point for an annual ceremony of significance to both the mining heritage of Cumberland and the broader history of the labour movement in B.C. and beyond. Miners’ Memorial Day had its origins in a 1985 Sudbury, Ontario event to honour four miners killed in a June 10, 1984 accident. The positive response to that commemoration led union organizer Rick Briggs to expand his vision afield. Retired Mine Mill representative Barney McGuire suggested that Cumberland would be an appropriate venue. The first Workers’ Memorial Day held in B.C. took place in Cumberland on June 21, 1986. The dedication of two cairns at the Mine no. 6 site and at the Japanese Cemetery celebrated the memory of the more-than-300 miners who lost their lives in the mines of Cumberland over the course of a half-century.

The second Miners’ Memorial Day saluted Goodwin as a “union organizer and labour martyr,” and sponsored a story-board commemoration of his union activities at Comox Lake’s main beach.[31] Over the next years, rituals emerged. Cumberland Miners’ Memorial Day commemorations came to be characterized by remembrance ceremonies, pancake breakfasts, theatrical productions, and songs of the workers folk nights. The central rituals included the laying of wreaths on the grave of Ginger Goodwin and of roses on Miners’ Row, the area of the cemetery with the graves of those who had died in mining accidents, including men whose bodies had been so badly burned by fire that they were unidentifiable. Donations linked to the Goodwin wreaths helped to fund the labour history activities of the Cumberland Museum and Archives.

Various individual Miners’ Memorial Day ceremonies initiated special remembrance projects. In 1988, former B.C. MLA Rosemary Brown participated in the unveiling of a large cairn commemorating the contributions of Cumberland’s black community. Mayor Bronco Moncrief presided over the dedication of a smaller marker identifying Miners’ Row in the cemetery the next year. In 2016, a year in which the annual conference of the Pacific Northwest Labour History Association was held in the Comox Valley in conjunction with Miners’ Memorial Day, a large stone plaque outlining the accomplishments of labour activist and long-time Comox Lake resident Joe Naylor was unveiled in front of the museum. That ceremony paralleled the 1997 Miners’ Memorial Day dedication of a new gravestone and plaque marking Naylor’s 1946 burial beside Ginger Goodwin. Throughout the years, the organizers, including the Campbell River, Courtenay and District Labour Council, remained focused upon not just the sacrifices of past miners but upon the needs of present-day workers. Featured speakers, such as B.C. Federation of Labour President Jim Sinclair in 2000 and NDP national party leader Jack Layton in 2003, consistently connected past, present, and future in their prepared remarks. “This little mid-Vancouver Island town has coal dust in its soul,” wrote journalist Stephen Hume in 2004. “Its annual Miners’ Memorial day ceremony provides a moment where you may yet encounter the old left at its unvarnished best – earthy, honest and unshakeably engaged with life.”[32]

The 2018 edition of Miners’ Memorial Day centred upon the 100-year anniversary of the death of Ginger Goodwin. The Cumberland Museum and Archives sponsored a series of programmes and events: tours, lectures, music, theatre, visual art, and an exhibit that explored Goodwin’s legacies and their relationship to contemporary issues of social justice, labour, ethnicity, and gender. The highlight was the June 23rd reenactment of Ginger Goodwin’s funeral procession, with the citizens of Cumberland marching down Dunsmuir Avenue in period dress. “The funeral reenactment was powerful as it brought together many layers of people moved by Goodwin’s story while providing a profound connection to place,” explained the museum’s Engagement Coordinator Anna Rambow. “It demonstrated that there is a hunger to experience history through immersive experiences and human connection.”[33] The Cumberland Museum and Archives received the 2019 Governor General’s History Award for Excellence in Community Programming for the Goodwin anniversary commemorations. Executive Director Robin Folvik accepted the recognition “on behalf of all of those who have worked to keep the memory of Albert ‘Ginger’ Goodwin alive over the years.”[34]

The June 23, 2018 Miners’ Memorial Day graveside ceremony became the occasion upon which the province’s NDP government announced it would be designating July 27, 2018, the anniversary of Goodwin’s killing, as “Ginger Goodwin Day.” A later official proclamation outlined the reasons for this designation:

Whereas Albert “Ginger Goodwin played a prominent and fundamental role in the history and growth of British Columbia’s labour movement, and

Whereas Ginger Goodwin served as a passionate advocate who propelled forward the issues of social justice, fairness, and health and safety in the workplace to ensure their evolution so workers could build better lives, and

Whereas our province’s economy is driven and supported by millions of men and women who work in improved environments because of Ginger Goodwin’s dedication and commitment to workers, and

Whereas the Government of British Columbia wishes to acknowledge his substantial contribution to this province’s labour movement, celebrate his legacy and mark the 100th anniversary of his death,

Now know ye that, We do by these presents proclaim and declare that July 27, 2018 shall be known as ‘Ginger Goodwin Day’ in the Province of British Columbia.[35]

Local MLA Scott Fraser also announced at the June 23, 2018 graveside service that the provincial government had decided to dedicate the section of the Inland Highway on the edge of Cumberland as “Ginger Goodwin Way.”[36]

*

The highway designation became but the latest episode in a controversy dating back to the years immediately following the 1990 publication of Mayse’s Goodwin biography. In the early 1990s, former Mine Mill organizer and local Cumberland historian Barney McGuire approached the provincial government bureaucrat Jim Green and noted that the new island highway would pass very close to Goodwin’s grave.[37] Green agreed that a tribute would be fitting and was soon approaching Cumberland’s Village Council asking their support for the naming of part of the highway after Goodwin. “I came up with the name Ginger Goodwin Way, the word ‘way’ having a double meaning: one is a road, the other is a philosophy,” Green later recalled.[38] In 1996, the NDP government of Glen Clark declared that the eleven-kilometre stretch of the highway stretching from the Trent River to the Puntledge River would become the Ginger Goodwin Way. Large signs were installed in time for the opening of the highway a couple of years later. By this time, however, Cumberland’s Council was objecting to the Goodwin Way appellation and suggested Miners’ Way as a suitable substitute. The Council’s appeal for a name change was rebuffed by the provincial government.[39]

Then, shortly after the election of a new B.C. Liberal government and just before Labour Day in 2001, the signs came down and the Ginger Goodwin Heritage of B.C. signpost was moved from the Buckley Bay rest-stop to the less prominent Cumberland Cemetery. Newly-elected MLA Stan Hagen suggested that it was inappropriate to name part of the highway after an historical figure.[40] Cumberland resident Frank Carter, the grandson of a miner who had worked in Ginger Goodwin’s No. 5, retrieved three Ginger Goodwin Way signs from a waste pit. He gave one to the museum and another to the NDP party president. “He promised that when the NDP got back into power, those signs were going back up,” Carter remembered in 2013.[41] Other locals covered over the Dunsmuir Avenue street signs in the centre of Cumberland with specially-designed Goodwin Way stickers.

Then, shortly after the election of a new B.C. Liberal government and just before Labour Day in 2001, the signs came down and the Ginger Goodwin Heritage of B.C. signpost was moved from the Buckley Bay rest-stop to the less prominent Cumberland Cemetery. Newly-elected MLA Stan Hagen suggested that it was inappropriate to name part of the highway after an historical figure.[40] Cumberland resident Frank Carter, the grandson of a miner who had worked in Ginger Goodwin’s No. 5, retrieved three Ginger Goodwin Way signs from a waste pit. He gave one to the museum and another to the NDP party president. “He promised that when the NDP got back into power, those signs were going back up,” Carter remembered in 2013.[41] Other locals covered over the Dunsmuir Avenue street signs in the centre of Cumberland with specially-designed Goodwin Way stickers.

The Goodwin Way controversy became the impetus for, amongst other things, a November 2001 benefit concert in Cumberland, a 2010 Vancouver art exhibit, and Neil Vokey’s superb 2016 feature-length documentary “Goodwin’s Way.” The benefit concert was headlined by the punk rock band D.O.A., whose lead vocalist Joe Keithley is but one of many artists to write songs about Ginger Goodwin.[42] The “Ginger Goodwin Way” Or Gallery exhibit featured contemporary art and text that explored the theme of contested stories and histories, including reinterpretations, misinterpretations, and unofficial narratives.[43] Perhaps the most intriguing piece was Raymond Boisjoly’s description of “Our Way,” an installation “constructed piecemeal from deaccessioned fragments of roads near and far from within the province of British Columbia.”[44] Musing about how history is constructed in his essay entitled “The Name of the Road May Tell You Where You Are Going,” Boisjoly was reminded of the mythic Argo, whose every piece was gradually replaced so that eventually no part of the original ship survived. “The removal of Goodwin’s name from its namesake highway does not obliterate his story,” wrote Boisjoly, “it just demands a persistence in recalling what it was that Goodwin did to become such a contentious figure, how he had a highway named for him, and how that highway is no longer named Ginger Goodwin Way in any official capacity.”[45]

A January 17, 2018 letter from Canadian Union of Poster Workers National President Mike Palecek to the new NDP Premier John Horgan that implored for the reinstatement of the Ginger Goodwin Way powerfully portrays Goodwin as labour martyr. Describing the 1918 death as a murder, Palecek remembered the 2001 sign removals as a “gut-wrenching insult.” “It seems that every town in B.C. has a street or a park named after Robert Dunsmuir, the coal baron that owned the mines in Cumberland,” he wrote. “But any attempt to honour B.C.’s rich history of working class struggle is met with disdain and scorn from the right wing. It is not enough for them that Ginger is dead; they try to kill his memory as well.” Palecek associated Goodwin not just with past struggles but with dreams of a better world to come. “Ginger’s legacy reminds us that nothing was ever ‘given’ to workers in this country. The rights that we have today were fought for, were bled for by courageous people like Ginger,” he concluded. “People who had the fortitude to accept the conditions imposed on them by those in power and who organized collective actions to demand better. That is why, 100 years later, the bosses still fear the memory of Ginger Goodwin.”[46]

Three decades on from publication, Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin is perhaps best approached as an example of the type of alternative narrative that Jesse Birch described in the 2010 “Ginger Goodwin’s Way” exhibit title essay as circulating by means other than the official narrative or even as a deaccessioned “Our Way” road fragment, to use the image introduced by Raymond Boisjoly in that same Vancouver art show. If the connections of family shape the pace, tone, approach, and substance of Mayse’s book, so too do the connections of place:

I grew up on stories of Cumberland and Bevan, Nanaimo and Wellington, the Vancouver Island coal towns where my grandfather . . . worked and my father grew up,” writes Mayse. “I knew the sweet smell of Cumberland in the rain was the smell of coal smoke . . . . I knew . . . the miners’ hall had an impressive wooden turret, a nickel bought a Kik-Cola in Chinatown, and the streets and sidewalks flowed with traffic even between shift whistles. I knew – and forgot – that Cumberland had never forgotten a great injustice done long ago, when my own parents were children.[47]

Mayse is at her best describing the details of the Big Strike in Cumberland or in displaying her knowledge of the local geography of the area and of the rhythms of fly fishing in its nearby streams. She lived in one of Cumberland’s original miner’s houses on Camp Road, on the far end of Dunsmuir Avenue, between 1989 and 1992, as she brought her book to completion.

It is striking the degree to which Mayse’s project overlapped with the formal institutionalization of Cumberland’s collective memory in the 1980s. The Cumberland and District Historical Society was organized in 1981, just as she began her research. Local historian Ruth Masters bound up her large “The Shooting of Ginger Goodwin” scrapbook in 1982, a labour of love that became a key resource for Mayse. That same year, Masters successfully applied to have a small waterway flowing into Comox Lake named Goodwin Creek. The museum’s curator Barb Lemky thanked Mayse for her participation in the 1989 Miners’ Memorial Day festivities.[48] The focus that year was on the renaming of a mountain in the vicinity of Goodwin’s shooting death as Mount Ginger Goodwin. A plaque with the following proclamation was cemented into the mountain in the Cruickshank Creek area:

Mount Ginger Goodwin was officially named by Cumberland Mayor Bronco Moncrief on Miners’ Memorial Day, June 24, 1989. Albert “Ginger” Goodwin, pacifist, socialist and trade unionist was shot by the Dominion Police on July 26, 1918. One of B.C.’s Labour martyrs, “A WORKER’S FRIEND,” Goodwin lies buried in the Cumberland Cemetery.[49]

The book launch for Mayse’s Goodwin biography then became the feature activity for Miners’ Memorial Day in 1990. Her June 23 lecture at the Cumberland Recreation Institute Hall was complemented by a ceremony at the Ginger Goodwin gravesite, the dedication of a commemorative sign honouring Cumberland’s mining families at Kin Park, and a tug-of-war challenge in which teams of eight were invited to test their muscles against the BCGEU Local 102 Corrections Team, bronze medalists at the 1989 World Police and Fire Games in Vancouver, with the proceeds being contributed to the Cumberland Museum and Archives.[50] Near the end of Ginger, Mayse salutes the centrality of Cumberland to her tale. “The spirit that somehow keeps Cumberland alive is also the spirit that fiercely defended Ginger Goodwin a long lifetime ago and for all the years since,” she declares. “It embodies one small industrial town’s resolve that this story is important and shall not be forgotten. This is Cumberland’s voice, despite all the other voices that join in, and this is Cumberland’s book.”[51]

Mayse self-consciously defined her role as helping to legitimate an alternative telling of the past. “Working people can choose to perpetuate the official history . . . or to challenge it,” she observed in 1991. “This is our history as working people. If we want it on record – not just the patronizing and distorted views of the privileged – we must speak out.”[52] Folded from its publication into the fabric of Cumberland’s history-telling, Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin has become one support for the Goodwin counter-narrative. The fictional miner in Michael Turner’s 2001 short story “The Death of Albert ‘Ginger’ Goodwin (As Told By A Very Old Man Who Wishes to Remain Anonymous)” describes the Mayse biography as “by far the best book on the topic – even though she never spoke to me when she wrote it.”[53] Likewise, contemporary labour activists are liable to draw from Ginger when discussing the life, death, and legacies of Goodwin.[54] In her penultimate chapter, Susan Mayse uses the mining metaphor of “Pulling Pillars” to explain her approach to history. It captures with humility and poetry the power of the past:

Quitting time at last. The miners emerge heavy-footed after a long shift, tools in hand, blinking as their lamps suddenly grow pale in the broader light. Another day, another shift, another meal on the table.

So with history. We explore out to the limits, extract what we can, and retreat toward our point of entry. But in dealing with history, we also try to make sense of our extraction. We try to understand not only fact, the serviceable fuel to create warmth and light but essence, the iridescent coal fossils compressed between the seams by relentless time, long lost from sight but shimmering again in rediscovered daylight.[55]

*

Dan Hinman-Smith teaches a wide variety of history and liberal studies courses at North Island College in Courtenay, with an emphasis upon world history and world religion. A Cumberland resident, he lives across the street from No. 6 Memorial Mine Park.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Susan Mayse, Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin (Madeira Park: Harbour, 1990), 11.

[2] Mayse, Ginger, 224-25.

[3] Mayse, Ginger, 55-56, 80-81, 84-85, 147, 185, 205.

[4] Roger Stonebanks, Fighting for Dignity: The Ginger Goodwin Story (Edmonton: Canadian Committee on Labour History, 2004); Susan Mayse Fonds, University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, http://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/index.php/susan-mayse-fonds-1900s-1920s .

[5] Jesse Birch, “Ginger Goodwin’s Way,” Ginger Goodwin Way (Vancouver: Or Gallery, 2013), 2.

[6] Vancouver Sun, August 2, 1918.

[7] Mayse, Ginger, 183-84.

[8] Ibid., 187.

[9] Mayse, Ginger, 210.

[10] Ibid., 209-10.

[11] Mayse, Ginger, 212.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 213.

[14] Bruce MacInnis, “Play Brings ‘Ginger’ Back,” Comox Valley Record, November 22, 1995.

[15] Susan Quinn, “Ginger Goodwin: Hero, Martyr or Movie Star,” Comox Valley Record, October 26, 2001.

[16] Ibid., 13.

[17] Mark Leier, “’Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin’ By Susan Mayse (Review),” Canadian Historical Review, 73 (December 1992): 541-44.

[18] Ibid.; Leier, “Plots, Shots, and Liberal Thoughts: Conspiracy Theory and the Death of Ginger Goodwin (In 1918),” Labour/Le Travail (Spring 1997): 215-24; Leier, “To Praise Ginger Goodwin is to Revere A Radical,” Tyee, July 25, 2014.

[19] Leier, “Plots, Shots, and Liberal Thoughts” Labour/Le Travail (Spring 1997).

[20] Ginger Goodwin, “Capitalism the Leveller,” Western Clarion, August 16, 1913.

[21] Stonebanks, Fighting for Dignity, 187.

[22] Ibid., 1.

[23] Mayse, Ginger, 179.

[24] “#156, Arthur Mayse,” BC Booklook, March 9, 2016, https://bcbooklook.com/2016/03/09/157-arthur-mayse/ .

[25] Stephen Hume, “Extraordinary Life of the Man Who Was Bill Mayse,” Vancouver Sun, March 25, 1992.

[26] Mayse, Ginger, 12.

[27] Vancouver Province, September 6, 1981.

[28] Mayse, Ginger, 214.

[29] Ibid., 208.

[30] Ibid., 207-208; Stonebanks, Fighting For Dignity, 164.

[31] Cumberland Museum and Archives Press Release, June 5, 1987, Miners’ Memorial Day Folder, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives.

[32] Stephen Hume, “Miners Paid for Today’s Workers’ Benefits with Their Blood,” Vancouver Sun, June 24, 2004, A15.

[33] “Cumberland Museum and Archives Wins Governor General’s History Award for Ginger Goodwin Celebration,” Cumberland Museum and Archives, January 13, 2020, http://www.cumberlandmuseum.ca/cumberland-museum-and-archives-wins-governor-generals-history-award-for-ginger-goodwin-celebration/. For a superb short video of the 100th anniversary village procession, see “Ginger Goodwin’s Funeral Re-enactment,” Fox and Bee Media, June 24, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jG-dchT0fj4 .

[34] Erin Haluschak, “Cumberland Receives National Award,” Comox Valley Record, January 14, 2020.

[35] “Canada, Province of British Columbia: A Proclamation,” July 26, 2018, http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/proclamations/proclamations/GngrGdwnDay2018 .

[36] “Stretch of Highway 19 Dedicated as Ginger Goodwin Way,” British Columbia News Release, June 23, 2018, https://archive.news.gov.bc.ca/releases/news_releases_2017-2021/2018TRAN0097-001267.htm .

[37] Jim Green, “Ginger Goodwin Way,” Ginger Goodwin Way, p. 14.

[39] Ibid.

[39] Jack Knox, “Grave Act of Vandalism Against A Labour Hero,” Times Colonist, June 22, 2019; Jack Knox, “Controversial Labour Leader Ginger Goodwin Rises Again on Road Signs,” Times Colonist, March 15, 2018; Cheryll Coull, “Shot Down Again: Ginger Goodwin is Erased from B.C.’s Lexicon of Highway Names, Beautiful British Columbia, 44 (Spring 2002); Ian Lidster, “Minister Rejects ‘Miners’ Way,’” Comox Valley Echo, September 10, 1999.

[40] Birch, “Ginger Goodwin’s Way,” Ginger Goodwin Way, p. 21.

[41] Frank Carter, Interviewed by Neil Vokey, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives, 2013.

[42] An incomplete playlist of Ginger Goodwin songs include the following: Gordon Carter, “The Day They Shot Ginger Down”; Aengus Finnan, “Marching Ginger Goodwin”; “The Ballad of Ginger Goodwin,” Richard von Fuchs (1978); Bill Gallaher, “Ballad of Ginger Goodwin”; John Gogo, “Three Letters Home” (2015); Joe Keithley, “Ginger Goodwin” (1999); Grant Olson, “Dan Campbell Killed Ginger Goodwin” (2009); Wyckham Porteous, “Cumberland Waltz”; and David Rovics, “Song for Ginger Goodwin” (2015).

[43] Jesse Birch, ed., Ginger Goodwin Way (Vancouver: Or Gallery, 2013).

[44] Raymod Boisjoly, “The Name of the Road May Tell You Where You Are Going,” Ginger Goodwin Way, 113.

[45] Ibid., 115-16. Boisjoly is probably confusing Jason’s Argo here with the Ship of Theseus. The classical writer Plutarch suggested that the Athenians displayed the ship of the mythic Athenian king and Minotaur-slayer from before the time of the Trojan War to the fourth century BCE, replacing decaying planks with new timber, thus leading philosophers to argue whether the vessel was indeed still the same ship. The mythic Jason, in turn, met his end as an old man crushed under the weight of a rotten beam that fell from the Argo. Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives, Volume I, trans. John Dryden (New York: Modern Library, 2001), 13-14.

[46] Mike Palecek to John Horgan, “Restore the Ginger Goodwin Way,” January 17, 2018, Ginger Goodwin Folder, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives.

[47] Ibid., 211-12.

[48] Barb Lemky to Susan Mayse, “Re: Miners’ Memorial Day Naming of Mount Ginger Goodwin,” July 3, 1989, Ginger Goodwin Susan Mayse’s Book File,” SPF 006-003, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives.

[49] “Proclamation – Mount Ginger Goodwin,” June 24, 1989, Ginger Goodwin Folder, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives. Mayor Bronco Moncrief mentioned to film-maker Neil Vokey that the plaque had been vandalized and removed despite the fact that it had been anchored in place. (William “Bronco” Moncrief, Interviewed by Neil Vokey, 2013, Goodwin’s Way Folder, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives.

[50] “Goodwin Author to Speak,” Comox District Free Press, June 13, 1990.

[51] Mayse, Ginger, 219.

[52] “Author Wins With ‘Ginger,’” Comox Valley Record, September 13, 1991.

[53] Michael Turner, “The Death of Albert ‘Ginger’ Goodwin (As Told By A Very Old Man Who Wishes to Remain Anonymous),” Ginger Goodwin Way, 67.

[54] See, for example, Brian Charlton, Interviewed by Neil Vokey, 2013, Goodwin’s Way Folder, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives; Sy Pederson, Interviewed by Neil Vokey, 2013, Goodwin’s Way Folder, Community Research Room, Cumberland Museum and Archives.

[55] Mayse, Ginger, pp. 200-201.

6 comments on “#848 The ballad of Ginger Goodwin”

Thanks for a thoughtful and well-researched review, Dan. My further thoughts are posted at https://susanmayse.ca/creation-and-myth/.

Thank you, Susan, for your gracious response to my review. Your own extensive three-decades-on reflections on the writing of “Ginger” do more to place your book in context than do my comments. I encourage readers to follow your link above. We have lost an appreciation for myth in the modern world. I love the story of Gilgamesh, but also feel the pull of the story of Ginger Goodwin. It’s a story told by many to frame the meanings of their lives, and you have done as much as anyone to pass it along.

I had always associated Ginger Goodwin with the fight against the deplorable working conditions in Dunsmuir’s coal mines and I knew about his unfortunate death. However, Dan Hinman-Smith’s article gave me an enhanced perspective on Goodwin’s life and his significant contribution to British Columbia’s history. His story deserves to be better known.

Thanks Dan – for a very thorough review. Just FYI, my records from Fighting For Dignity: The Ginger Goodwin Story are at Simon Fraser University: https://www.lib.sfu.ca/system/files/28909/FINDING%20AID%20GOODWIN.pdf

Best wishes, Roger Stonebanks

BRAVO Daniel! Quite simply a meta-review of the first order with an unflinching critique of the fundamentals of the book and the implications of its re-issue some three decades later.

Tremendous.

Thank you for your very generous words, Grahame.