#847 Hedonism, pleasure, ethics

ESSAY: The Will to Pleasure: Hedonism, Ethics, and Aesthetics from the Ancient World to the Present Age

by Eryn Holbrook

*

When Christianity and Marxism end their shared reign, we will need visions of new possibilities. There is always one fixed point: the body. Not a body of Platonic ideas, nor a body cut in two, carved out, mutilated, and dualistic, but a body of postmodern science: flesh that is living, amazing, meaningful, rich in potential, bearing forces still unknown, and worked on by still unharnessed powers. — from Michel Onfray, A Hedonist Manifesto

*

Hedonists like Michel Onfray argue that the pursuit of pleasure is the highest good and that all human action should aim towards living a more pleasant life. A study of our attitudes towards pleasure will reveal a long-standing struggle between the soul and the body that parallels a philosophical conflict between formal and material reality. This fight for ideological dominance started in the ancient world and continues to this day. Attitudes towards pleasure have shifted dramatically over the centuries, partly as a result of changes in how we perceive our bodies and value (or reject) our instinctual desires. Tracing this shift can be tricky as the definition of what constitutes ‘pleasure’ has changed from a state of sensory enjoyment located in the body, to little more than the absence of pain, to a distinction between ‘lower-’ and ‘higher-order’ experiences. Understanding the nature of this transition can help us re-evaluate our current attitudes towards pleasure, sensuality, and passion.

The specifics of our modern attitudes to hedonism can be illuminated by an examination of hedonism’s historical roots, the classical and Christian arguments for and against it, and the introduction of Utilitarianism and Aestheticism in the 19th century. Classical and early Christian objections to the hedonist’s definition of pleasure as ‘the good’ can be found in the works of Plato and Boethius. Using the character of Callicles from Plato’s Gorgias as a guide, I will examine how different attitudes to pleasure stack up against Callicles’ hedonistic imperative — that it is better to have “as much flowing in [of pleasure] as possible” than to cut oneself off from the flow of pleasure in order to live temperately (or ascetically) “like a stone” (Plato, p. 83).

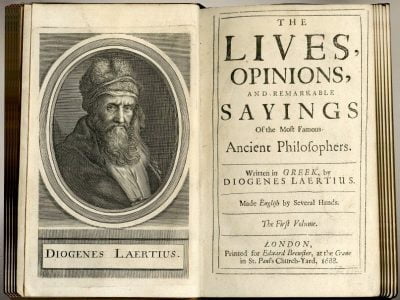

In order to fully appreciate Callicles’ arguments for pleasure’s supremacy, it is necessary to survey the doctrines held by two of the most influential ancient hedonist schools: the Cyrenaics and the Epicureans. In the 4th century BCE, a school of philosophy was formed in the city of Cyrene on the coast of present-day Libya. The Cyrenaics, as they came to be known, promoted a way of life that was devoted to the pursuit and sustainment of sensual pleasure. They advocated for living in the present moment and were generally indifferent to the source or consequences of the pleasure experience. What mattered to the Cyrenaics was the experience itself, not its cause. The 3rd century biographer Diogenes Laertius devotes a chapter to the Cyrenaics in his Lives of Eminent Philosophers. He outlines one of the primary doctrines of Cyrenaic philosophy, namely that pleasure is the highest good and is critical to achieving the good life: “And they consider that particular pleasure is desirable for its own sake; but that happiness is desirable not for its own sake, but for that of the particular pleasure” (Diogenes, p. 89).

In his 2015 book, The Birth of Hedonism: The Cyrenaic Philosophers and Pleasure as a Way of Life, Kurt Lampe presents a history of the Cyrenaics from their founder, Aristippus, to the innovative Theodorus ‘The Godless’. As Lampe explains, “[t]he Cyrenaics reflectively affirm their intuitive attraction to pleasure and commit themselves to working through this decision’s life-shaping consequences” (Lampe, p. 1). While the Cyrenaics and Epicureans were compatible in their belief in materialism over idealism, they differed in a number of ways. The Cyrenaics’ approach to hedonism was, according to Lampe, more radical, egoistic, and solipsistic than their ideological successors, the Epicureans. Whereas the early Cyrenaics accepted pleasure in all its forms — be it licentious sexual indulgence or intoxication — Epicureans held that the pleasant life required restraint and sobriety. Quoting from Epicurus’ letter to Menaeceus, Diogenes writes:

When, therefore, we say that pleasure is a chief good, we are not speaking of the pleasures of the debauched man, or those which lie in sensual enjoyment, as some think who are ignorant, and who do not entertain our opinions, or else interpret them perversely; but we mean the freedom of the body from pain, and of the soul from confusion (Diogenes, p. 471).

Given this sharp contrast between the two dominant ancient schools, it is clear that a single definition of hedonism will not suffice. The Cyrenaics were primarily concerned with sensual enjoyment and pleasures of the body. Plato’s initial characterization of Callicles, as we will see, is more closely aligned with the Cyrenaic hedonists than the Epicureans.

In addition to upholding pleasure as the highest good, two additional doctrines serve as the foundation for Cyrenaic hedonism: sceptical indifference and presentism. With regards to scepticism, Cyrenaics state that it is impossible for us to know anything about the external world with any degree of certainty. While we can know the qualities of our sense experiences, whatever is responsible for producing those sensations is inaccessible and, hence, of little importance to us. Lampe explains that the Cyrenaics “not only want to argue that we are less certain about the external world than about our own experiences, they want to argue that we cannot know external reality at all” (Lampe, p. 39). This is an important point to consider when evaluating Cyrenaic morality. If the only thing I can be certain of is the pleasure or pain I feel myself, how can I be expected to know the quality (or veracity) of the pleasure (or pain) felt by others?

The Cyrenaic uses this argument to justify an indifference to both the source and consequences of each pleasure experience. Pleasure is always choice-worthy for its own sake, “even when, given the circumstances, it ought not to be chosen… In other words, its intrinsic ability to motivate choosing is a matter of its self-evident phenomenal character, which is not altered by prudential circumstances.” (Lampe, p. 42) Cyrenaic indifference leads to a morally problematic, but logically consistent, outcome of this solipsistic form of hedonism. Given that I am unable to access anything beyond my own internal experience — including the feelings, motives, or experiences of others — the only thing that should matter is the experience itself. But if I am to remain indifferent to the source or consequences of my pleasure, how do I know if those pleasure-seeking activities are harmful or benign? The Cyrenaic would dismiss this question as irrelevant.

The final key doctrine of Cyrenaic philosophy is their privileging of the present moment. If your mind is fully occupied with the pleasure of the immediate experience, the Cyrenaic contends, concerns of yesterday and tomorrow can be extinguished. This perspective was held by Cyrenaicism’s founder, Aristippus, and was practiced by his followers. Lampe calls this ‘Aristippean presentism’:

Aristippus very clearly says that he only cares about what is present; he does not care about what has already happened or what may happen in the future. Furthermore, he exhorts his listeners to adopt the same position (Lampe, p. 64).

Presentism allows the Cyrenaic to argue for the superiority of pleasure over all other possible experiences. While some may argue that pleasure is imperfect because it is fleeting, the hedonist will claim that the only thing that matters is the present moment. While in that moment, one should be occupied by feelings of pleasure rather than suffering. Both the Cyrenaics and Epicureans used this ‘presentist’ approach to address the pains of anxiety (worries about the future) and regret (concerns about the past). Epicurus, in his letter to Menaeceus, explains his position with the statement: “the future is not our own, I mean so that we can never altogether await it with a feeling of certainty that it will be, nor altogether despair of it as what will never be” (Diogenes, p. 470).

Both the Cyrenaics and the Epicureans agreed that pleasure is the greatest good. Plato and Boethius, on the other hand, object to equating the good with anything related to the body or earthly experience. For these philosophers, the good must be immaterial. It must transcend corporeal existence in order for it to fit with Plato’s concept of the ideal Forms. This debate plays out in the dialogue between Socrates and Callicles in Plato’s Gorgias. In this dialogue, Callicles takes a Cyrenaic-like stance on the subject of pleasure:

The truth, Socrates, which you profess to be in search of, is in fact this: luxury and excess and license, provided that they can obtain sufficient backing, are virtue and happiness; all the rest is mere pretense, man-made rules contrary to nature, worthless cant (Plato, p. 81)

Callicles calls on the laws of nature to prove his point. Anyone who claims that licentious indulgence is unlawful has become enslaved by the false, human-made laws of society rather than nature’s law. Socrates objects to Calicles’ choice to associate “luxury and excess and license” with true well-being and happiness. Socrates argues that pleasure cannot serve this role because the desire for pleasure is painful, and that pain and pleasure come to an end simultaneously when the desire is satiated: “When you speak of someone drinking when thirsty you imply the experience of enjoyment and pain together” (Plato, p. 87). He concludes that pleasure is inferior because “good is not identical with pleasure nor evil with pain. The one pair of contraries comes to an end together and the other does not, because they are different. How then can pleasure possibly be the same as good, or pain as evil?” (Plato, p. 89).

Socrates attempts to denounce Callicles’ privileging of pleasure by illustrating the value of temperance metaphorically. Socrates describes two men, both of whom own several casks filled with wine, honey, and milk. The first man’s casks are sound; the second man’s casks are full of holes. Once the first man fills his casks, he “will not need to draw in any more or give himself any concern about it.” (Plato, p. 82) The second man, however, has to continuously fill his casks as their contents will leak out at the same rate as they are filled. Socrates believes that this analogy reveals the attitude of temperance to be superior to licentiousness, but Callicles isn’t convinced. “The man who has filled his casks no longer has any pleasure left,” Callicles argues, “once his casks are filled he lives like a stone, with no more pleasure and pain. But the pleasure of life consists precisely in this, that there should be as much flowing in as possible.” (Plato, p. 83). For Callicles, the continuous “flowing in” of pleasure is all that matters. To live in the present moment is to live in an eternally flowing pleasure-state. To halt the flow is to live ascetically “like a stone,” something a hedonist would abhor. Like Aristippus, Callicles holds that pleasure is not only the most desirable choice, it is equivalent to the greatest good.

Plato’s Gorgias attempts to expose the hedonists’ position to be unfounded and easily dismissible. Over the course of the dialogue, Socrates persuades Callicles to drop his original position — that all pleasures are equally good — and to accept that there are both good and bad pleasures. “What you are now saying, apparently” Socrates states, “is that some pleasures are good and some bad. Is that right?” (Plato, p. 92) Callicles reluctantly accedes this point and abandons his strict Cyrenaic position. This dialogue reveals that both Callicles’ position on pleasure and the Cyrenaics’ dedication to hedonistic materialism are incompatible with Plato’s Idealism. As Lampe points out, Plato was no stranger to Aristippus; they were both students of Socrates: “We do not know when and why Aristippus first left Cyrene for mainland Greece, but it is clear that he became one of Socrates’ well-known associates” (Lampe, p. 16). In fact, Plato may have intended Callicles to serve as a stand-in for Aristippus himself. There may have been a rivalry between the two disciples: “all we can say with any degree of confidence is that he got along well with Aeschines and poorly with Xeonophon and Plato” (Lampe, p. 16). In a time when several philosophical schools were competing for dominance, it is not inconceivable that Plato would have had a strong motivation to discredit Aristippean hedonism. What is revealed in a text like Plato’s Gorgias is the fact that, in the ancient world, there were many competing interpretations of what constitutes the greatest ‘good’. Which activities contribute to living a ‘good life’ and allow to achieve perfect happiness were still up for debate.

This quest for a definition of the greatest good occupied philosophers and theologians long after Plato’s time. For example, Plato’s influence can be readily detected in the works of 6th century Christian philosopher, Boethius. In Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius’ narrator — in a moment of spiritual crisis spurred by his seemingly senseless imprisonment — enters into a dialogue with an ethereal manifestation of philosophy called ‘Lady Philosophy’ in the P.G. Walsh translation. Responding to the prisoner’s complaints about his current situation, Lady Philosophy counsels him not to dwell on what he has lost because all earthly possessions are impermanent and, therefore, not worthy of lament. Instead, she insists that the prisoner should focus his efforts on attaining happiness, which is the one and only path to achieving perfection. This divine happiness serves as the ‘greatest good’ because it is completely self-sufficient; nothing more can possibly be added to it to make it greater than it is:

This is the good which once attained ensures that no one can aspire to anything further. Indeed, it is the highest of all goods, and gathers all goods within itself. If any good were lacking to it, it could not be the highest good, since some desirable thing would be left outside it. Thus it is clear that happiness is the state of perfection achieved by the concentration of all goods within it (Boethius, p. 41).

Any object or state of being that claims to be perfect must be lacking in nothing. For Boethius, the hedonist’s pleasure state does not qualify because the experience is fleeting and can always be improved upon. Lady Philosophy commands the prisoner to accept his state and abandon the “ephemeral happiness” that was previously bestowed on him by fickle fortune (Boethius 20). By rejecting earth-bound pleasures such as wealth, fame, and honour, she assures him that he will be free from suffering:

If on the other hand the mind is happily self-aware, is loosed from its earthly prison, and in freedom makes for heaven, it surely scorns all earthly business, and in the enjoyment of heaven rejoices at having been removed from things of earth (Boethius, p. 36).

It is not surprising that Boethius would reject the comforts of a hedonistic way of life given his lack of access to anything physically pleasurable during the Consolation’s composition. As Lady Philosophy points out, the pursuit of bodily pleasures is, in her estimation, so worthless that it is hardly worth mentioning:

Need I speak of bodily pleasures, when the pursuit of them is full of anxiety, and over-indulgence in them brings remorse? How grievous are the illnesses, and how hard to bear the pains which they frequently inflict on the body as reward, so to say, for the wickedness of those who enjoy them! I boast no knowledge of the delight which their impact brings, but whoever is willing to recall his low inclinations will know that the outcome of pleasure is melancholy (Boethius, pp. 50-51).

A belief that the pursuit of bodily pleasures will lead to anxiety, melancholy, and remorse, anticipates the Christian doctrine that pleasures derived from bodily experiences (e.g., food and sex) are cardinal sins (e.g., gluttony and lust) and must be avoided. Once a contender for the greatest good in the ancient world, bodily pleasures were transformed into the vilest sins. This revaluation of pleasure as ‘evil’ serves as an example of what Nietzsche calls the triumph of ‘slave morality’ in On the Genealogy of Morals:

The “masters” have been done away with, and with them their aristocratic morality has vanished; the morality of the low classes has triumphed… everything is obviously becoming Judaized, or Christianized, or vulgarized (what do the words matter?) (Nietzsche, p. 24).

The hedonist’s privileging of the corporeal body over the incorporeal spirit is incompatible with Boethius’ Christian values, just as it was shown to be antithetical to Plato’s transcendental idealism. For Nietzsche, this denial of the body intensifies with Christianity’s rise and manifests as an extreme, life-denying ideology that manifests as religious asceticism: “…hatred of anything human, animal or material; abhorrence of the senses, of reason itself; fear of happiness and beauty; the desire to escape from all illusion, change, growth, death, wishing, even from desiring itself… a wish for oblivion, an aversion to life, a repudiation of everything vital to existence…” (Nietzsche, p. 145). Ideologically, asceticism stands in direct opposition to hedonism. Using Socrates’ analogy of the casks, the ascetic has not only stopped the flow of pleasure but has upended the vessel and emptied it of its contents.

An echo of Nietzsche’s critique of asceticism can be found in the works of 19th century philosopher John Stuart Mill. In his 1863 treatise, Utilitarianism, Mill criticizes the martyr who sacrifices his happiness in the name of idealism: “…but he who does it, or professes to do it, for any other purpose, is no more deserving of admiration than the ascetic mounted on his pillar. He may be an inspiriting proof of what men can do, but assuredly not an example of what they should” (Mill, p. 23). Mill builds on a familiar hedonist doctrine in his belief that “the ultimate end… is an existence exempt as far as possible from pain, and as rich as possible in enjoyments, both in point of quantity and quality” (Mill, p. 17). Mill claims that the concept of utility, as defined by philosophers like Epicurus and Bentham, is “pleasure itself, together with the exemption of pain” (Mill, p. 8). He recognizes that there are many who reject the core tenets of hedonism on moral grounds. Mill believes these objections are unfounded because both Utilitarianism and hedonism aim to reduce suffering and bring happiness and pleasure to the greatest number of people. They provide a similar moral framework to guide human actions. Unlike the Cyrenaics, however, Mill believes that we can both understand and measure how our pleasure-seeking activities impact others, and that we should consider the consequences before acting on our desires:

I must again repeat, what the assailants of utilitarianism seldom have the justice to acknowledge, that the happiness which forms the utilitarian standard of what is right in conduct, is not the agent’s own happiness, but that of all concerned (Mill, p. 24).

Mill further attempts to placate his objectors by categorizing particular pleasures as ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ — the higher-order pleasures being more virtuous and choice-worthy than the lower:

The comparison of the Epicurean life to that of beasts is felt as degrading, precisely because a beast’s pleasures do not satisfy a human being’s conceptions of happiness. Human beings have faculties more elevated than the animal appetites, and when once made conscious of them, do not regard anything as happiness which does not include their gratification (Mill, p. 11).

For Mill, pleasures that reside primarily in the mind, and require engagement with the intellect, should be exalted; pleasures of the body should be devalued. He claims that anyone who is ‘cultured’ enough to appreciate higher-order pleasures would choose them over pleasures of the body:

Now it is an unquestionable fact that those who are equally acquainted with, and equally capable of appreciating and enjoying, both, do give a most marked preference to the manner of existence which employs their higher faculties (Mill, p. 12).

In contrast to Mill’s Epicurean-influenced Utilitarianism, the Cyrenaics held bodily pleasures in high esteem. While generally indifferent to the source of a given pleasure, the Cyrenaics acknowledged that bodily pleasures are, on the whole, more pleasurable than those situated in the mind. As Lampe explains, for the Cyrenaics “only bodily pleasure and pain are the ends… bodily pleasure and pain are more completely good or bad than their mental analogues” (Lampe, p. 55). Given this, the Cyrenaics would certainly take issue with Mill’s famous proverb, “[i]t is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied” (Mill p. 14).

The aesthetic appreciation of beauty — one of Mill’s higher-order pleasures — became a common theme in visual art, music, poetry, and prose in the 19th century. The aesthetic experience begins at the senses but requires engagement with the mind’s faculties. Examples of this abound in the works of the century’s most celebrated artists and writers. Feelings of sensuality are vividly evoked by works of the Pre-Raphaelite painters.

The tension wrought by delighting in — and ultimately being consumed by — sensual excess is artfully illustrated in Christina Rossetti’s poem “Goblin Market”. Similarly, Baudelaire wrestled with pleasure’s duplicitous nature (and its inseparable partner, pain) in poems like “The Mask” and “Meditation”.

Perhaps the most explicit celebration of 19th century aesthetic hedonism can be found in the works of Walter Pater. He identifies the rebirth of hedonistic values in the Middle Ages in his 1853 book, The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry:

One of the strongest characteristics of that outbreak of the reason and the imagination, of that assertion of the liberty of the heart, in the middle age, which I have termed a medieval Renaissance, was its antinomianism, its spirit of rebellion and revolt against the moral and religious ideas of the time. In their search after the pleasures of the senses and the imagination, in the care for beauty, in their worship of the body, people were impelled [sic] beyond the bounds of the Christian ideal and their love became sometimes a strange idolatry, a strange rival religion (Pater, pp. 19-20).

Pater recognized that the desire for sensual pleasure — what he refers to as a “rival religion” — was never fully quelled by the rise of Christian asceticism. Echoing the Cyrenaics, Pater declares, “[n]ot the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end… to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life” (p. 197). Lampe notes the profound influence ancient hedonism had on Pater’s writing:

[For Pater] the study of literature, art, and philosophy all pertain not only to transforming individual lives, but also to lifting Victorian culture out of what he saw as a spider’s web of conflicting impulses. It was for these purposes that he, like many of his contemporaries, reassessed the educational value of the works of Greco-Roman antiquity, medieval Europe, and the Renaissance (Lampe, p. 169).

Elevating aesthetic pleasure to a faculty of the intellect — and distancing it from the body — helped to defend it from puritanical censure. The aesthete acknowledges that beauty enters through the senses but quietly jettisons that experience out of the body and into the mind, where it can be sheltered from moral judgment. Mill redeems pleasure’s reputation by narrowing the definition of ‘good’ pleasures to include only those that are of a higher order and do not cause harm to others; Pater elevates pleasure so that it becomes nothing short of sublime. In so doing, they provide a counter-argument for Socrates’ insistence that some pleasures are ‘good’ while others are ‘bad’. Higher-order pleasures are always good and, therefore, always choice-worthy. They should be the ultimate pursuit and aim for all human actions.

In the centuries following Mill, pleasure became a popular topic for psychological study. In How Pleasure Works, psychologist Paul Bloom argues that the pleasure we derive from experiencing a work of art is a result of the object’s non-corporeal ‘essence’ rather than any particular sensation experienced in the body. “Much of the pleasure we get from art is rooted in an appreciation of the human history underlying its creation. This is its essence” (p. 122).

Bloom goes on to describe how, for humans, these higher-order mental pleasures are stimulating because they connect us with our history and culture; to appreciate them fully requires engagement with our mind. “For something such as a hunk of meat the essence is material,” he explains, “[but] for a human artifact such as a painting, the essence is the inferred performance underlying its creation” (Bloom, p. 138). Whereas the desire to satiate hunger is basic and universal, the ability to derive pleasure from the ‘essence’ of a cultural artifact must be learned. Bloom’s characterization of the experience’s ‘essence’ suggests an allegiance with Plato’s theory of Forms. A purely mental pleasure experience brings us closer to Plato’s transcendent realm and further from our corporeal bodies.

In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud refers to a similar dichotomy between mind and body when he describes the difference between the vivid satisfaction of our ‘wild’ as opposed to our ‘tame’ instincts. Like the Cyrenaics, he recognizes the superior intensity of satiating an untamed desire: “The feeling of happiness derived from a satisfaction of wild instinctual impulse untamed by the ego is incomparably more intense than that derived from sating an instinct that has been tamed” (Freud, p. 26). He cautions that directly indulging in the satisfaction of these wild desires “means putting enjoyment before caution, and soon brings its own punishment” (Freud, p. 24). Freud warns of the psychological repercussions caused by the eternal “flowing in” of pleasure championed by Callicles. Is the “punishment” he refers to an unavoidable consequence of the pleasure experience itself, or does it result from societal restrictions that form the foundation of our civilization? In A Hedonist Manifesto, Onfray acknowledges that a fear of punishment seems to be linked with pleasure. “Pleasure scares people,” he explains:

They are scared of the word and the actions, reality, and discourses around it. It either scares people or makes them hysterical. There are too many private and personal issues, too many alienating, intimate, painful, wretched, and miserable details. There are secret and hidden deficiencies. There are too many things in the way of just being, living, and enjoying. Hence, people reject the word. They produce spiteful critique that is aggressive and in bad faith or that is simply evasive. Disrespect, discredit, contempt, and disdain are all means for avoiding the subject of pleasure (Onfray, p. 83).

Why does the mere mention of pleasure evoke such paroxysms? This attitude is common but by no means universal. The ancient Cyrenaics were seemingly immune to such hysteria, while Boethius describes the experience of bodily pleasures as “full of anxiety” and a cause for remorse. For the Epicureans, the act of conflating pleasure with anxiety is counterintuitive — they used the pursuit of pleasure as a method for diffusing fear, anxiety, and suffering that seemed to plague much of human existence. In a strange twist, the hedonistic pursuit of pleasure is charged with producing anxiety rather than resolving it. Where did this idea of punishment for pleasure originate? Onfray points to a host of suspects: “dualism, the immaterial soul, reincarnation, the denigration of the material body, antipathy for life, and the ascetic ideal” are at the top of his philosophical hit list (p. 64). Like Nietzsche, Onfray insists that we must abandon our commitment to these ideas because they inevitably lead to suffering. Like Callicles, he asks us to choose pleasure over pain. Like Mill, he insists that following the hedonist path will lead to an Epicurean-like “serenity” and “tranquility”:

We should always have more pleasure than pain. In all hedonist ethics, suffering — the suffering that we undergo and that is inflicted upon us — is the absolute evil. Consequently, absolute good corresponds to pleasure, defined as the absence of troubles, a serenity that’s acquired, conquered, and maintained, a tranquility of soul and spirit (Onfray, pp. 104-5).

In order to set the groundwork for an ethical hedonism, it is necessary to confront the most common objections. These include worries about privation — by indulging in a pleasure I run the risk of depriving someone else of their own pleasure experience, or even causing suffering. Objectification is another concern of the anti-hedonist — the pleasure I derive from others may require me to treat them as a means rather than an end. Echoing Mill, Onfray declares that “pleasure is never justified if the pain of another must pay for it” (p. 106). Bloom is equally unequivocal in his assessment:

There is plenty of room to be judgmental. The issue isn’t true or false, rational or irrational. It is right and wrong. Some pleasures are immoral ones. Some of them lead to human suffering (p. 209).

When Socrates leads Callicles to admit that some pleasures are good, while others are bad, he is offering his interlocutor a chance to refine his position: pleasure is always choice-worthy so long as it doesn’t cause pain or suffering in another person. Therefore, there are no ‘bad’ pleasures, just bad consequences.

Setting aside the fact that achieving a truly ethical — let alone sustainable — state of pleasure may be impractical, the question of whether this state is even desirable must also be addressed. Libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick argues that, given the option to live a life of unlimited ‘virtual’ pleasure in exchange for your current life, we would choose to remain with the status quo. He attempts to prove this theory in his 1974 book, Anarchy, State and Utopia. Nozick invites his readers to participate in a thought experiment: “[s]uppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired,” he muses. Any joy, any dream, any pleasure would be yours. By connecting your brain to this device, you can become whomever you want, and lead any life you can imagine, so long as you are willing to ‘plug in’ to the machine and leave your current life behind. “All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain,” he explains — “[w]ould you plug in?” (Nozick, pp. 42-43).

In a brief analysis of possible common objections, Nozick’s concludes that, given the choice, we would not ‘plug in’, thus proving that humans are not hedonists. He gives three reasons for our choice to reject the hedonist option: 1. as human beings, we want to do certain things; 2. we want to be a certain way; 3. We want to be connected to what’s “real” (Nozick, p. 43). Nozick’s argument brings to light a key objection to hedonism: specifically, that living a life of pure pleasure is somehow inauthentic or counter to humanity’s telos. For example, imagine if you were to modify Nozick’s ‘Experience Machine’ hypothesis so that it always produces the most profound, heightened, and sustained pleasure possible. Not only are you able to live the life you want, but the life you are given is guaranteed to be devoid of suffering. In fact, it will offer something even better — that elusive, mythical, eternal pleasure-state. “What else can matter to us,” Nozick asks, “other than how our lives feel from the inside?”

Nozick set up this thought experiment in order to disprove the utilitarian-hedonist proposition that we can determine the choice-worthiness of an action based on the quantity of pleasure it produces — i.e., the best action is that which produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number, and that happiness is pleasure’s direct correlate. For Nozick, our decision not to ‘plug in’ proves that the fulfillment of dreams and the attainment of pleasure do not outweigh our desire to remain embedded in our current life, no matter how painful or disappointing it is. “We learn that something matters to us in addition to experience,” Nozick explains, “by imagining an experience machine and then realizing that we would not use it” (Nozick, p. 44).

Unlike previous anti-hedonist arguments, Nozick’s response has little to do with traditional moral values. It is a primarily teleological argument. Your choice to enter the machine or not depends on what you believe to be the purpose of life — what gives it meaning. The choice you make is extremely personal and subjective; for this reason, it is a difficult argument to prove or refute. If your primary concern is leaving your loved ones behind, modifying the experiment may alleviate those concerns — envisioning an immersive virtual world that includes friends and family members, for instance. Or, to take another example, the advent of mood-enhancing drugs that allow the participant to remain in “this” world while experiencing a sustained pleasure-state addresses a reluctance to dive into the unknown. Nozick assumes that there is still plenty of meaning left to discover in this world and that a manufactured or pharmaceutically-induced alternate reality would cut us off from accessing that deeper meaning. He also acknowledges that we are uncertain about the implications of a drug-induced pleasure state which some view as a ‘local’ experience machine:

[P]lugging into an experience machine limits us to a man-made reality, to a world no deeper or more important than that which people can construct. There is no actual contact with any deeper reality, though the experience of it can be simulated. Many persons desire to leave themselves open to such contact and to a plumbing of deeper significance. This clarifies the intensity of the conflict over psychoactive drugs, which some view as mere local experience machines, and others view as avenues to a deeper reality (Nozick, p. 44).

Given that there are a number of hypothetical pleasure-states that allow us to act freely and do not require us to exit the ‘real’ world, this leaves us with Nozick’s final argument against hedonism — that we want to be a certain way:

Someone floating in a tank is an indeterminate blob. There is no answer to the question of what a person is like who has long been in the tank. Is he courageous, kind, intelligent, witty, loving? It’s not merely that it’s difficult to tell; there’s no way he is. Plugging into the machine is a kind of suicide. It will seem to some, trapped by a picture, that nothing about what we are like can matter except as it gets reflected in our experiences. But should it be surprising that what we are is important to us? Why should we be concerned only with how our time is filled, but not with what we are? (Nozick, p. 43).

For Nozick, the act of surrendering yourself to experience constitutes the end of being; this being is what matters above experience. For this argument to work, we have to agree that being is superior to experience. Additionally, we have to accept that there is, in a fact, a difference between experience and being — that being is somehow a static, tangible state disconnected from the flux of experience. Nozick concludes that “[w]e learn that something matters to us in addition to experience by imagining an experience machine and then realizing that we would not use it” (Nozick, p. 44). For Nozick, this argument should dissuade us from believing that the hedonist’s pleasure experience is the greatest good. Perhaps he is correct — we are not, at the present time, exclusively motivated by pleasure, so how can pleasure be considered the most desirable end for human activity? Notably, his thought experiment doesn’t answer the question of whether or not we should aim towards pleasure; it simply suggests that we are often guided by other interests. The value of those interests is uncertain.

This brief survey of the classical origins of hedonism, its historical objectors, and contemporary champions, attempts to illustrate the nature and variety of arguments for and against pleasure as humanity’s ultimate aim. These continuously shifting attitudes often correspond with how we perceive and value (or dismiss) our bodies. The influence of Plato’s idealism on the rival Cyrenaic school may have been responsible for the Epicurean turn to establishing a revised definition of pleasure as the absence of suffering. In the 19th century, Mill attempted to appease puritanical objectors by providing several moral caveats: both the impact to others and location of the pleasure act (mind vs. body) were of prime importance. Honouring Callicles’ hedonistic imperative, contemporary philosophers like Michel Onfray continue to defend pleasure’s status as the greatest ‘good’. Those who sympathize with the hedonist position will confirm that Nozick’s question, “[w]ould you plug in?” has yet to be answered.

*

Eryn Holbrook is currently pursuing a Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Students program at Simon Fraser University where she also works as an IT manager. The GLS program has awakened in her an interest in classical mythology and German philosophy. She wrote “The Will to Pleasure” for Gary McCarron’s Spring 2020 seminar, LS 801: Reflections on Reason and Passion II. A musician and songwriter, Eryn has been a member of Vancouver’s independent music scene since the 1990s. She lives in East Vancouver with her partner, two sons, and a pair of backyard chickens named Bowie and Ozzy.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Works Cited

Bloom, Paul. How Pleasure Works: The New Science of What We Like. Norton & Co.: New York, 2010.

Boethius. Consolation of Philosophy. Trans. P. G. Walsh. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Diogenes Laertius. The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Trans. C.D. Yonge. J. Haddon & Son: London, 1853.

Freud, Sigmund. Civilization and Its Discontents. Trans. James Strachey. Norton & Co.: New York, 1961.

Lampe, Kurt. The Birth of Hedonism: The Cyrenaic Philosophers and Pleasure as a Way of Life. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1864.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. On the Genealogy of Morals. Trans. Michael A. Scarpitti. Penguin Group: Toronoto, 2013.

Nozick, Robert. Anarchy, State and Utopia. Basic Books: New York, 1974.

Onfray, Michel. A Hedonist Manifesto: The Power to Exist. Trans. Joseph McClellan. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

Plato, Gorgias. Trans. Walter Hamilton and Chris Emlyn-Jones. Toronto: Penguin Books, 2004.

2 comments on “#847 Hedonism, pleasure, ethics”

Thoughtful and thought-provoking!

Researched diligently!

Comprehensive!

Incredible!