#827 Conversations in a mountain cave

Conversations in a mountain cave

by Havi Neeman

*

We are pleased to present a literary mashup by Havi Neeman, a former student in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University.

A mashup is a creative work, such as a short story, novel, or song, that combines or blends pre-existing text or music into a single narrative or composition.

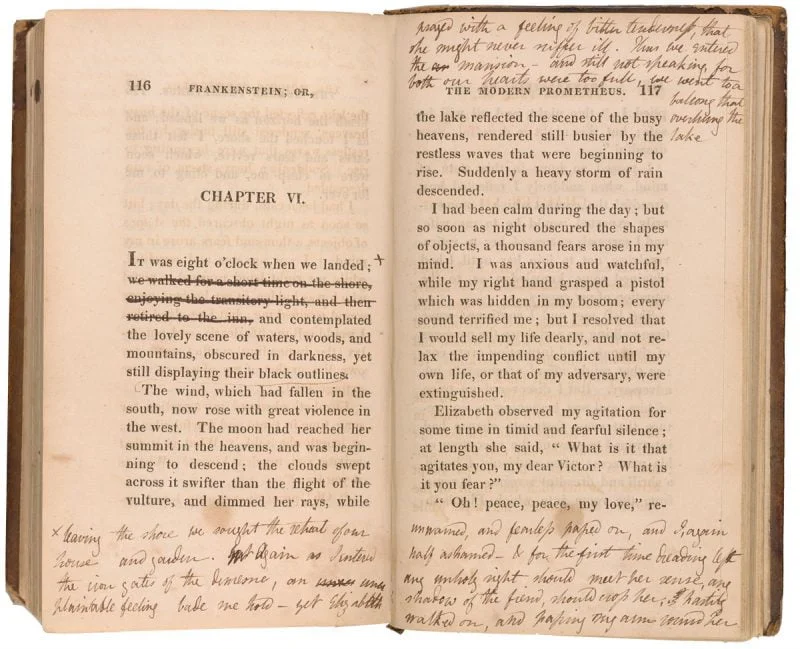

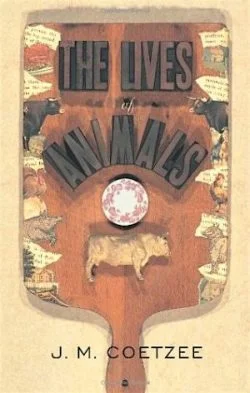

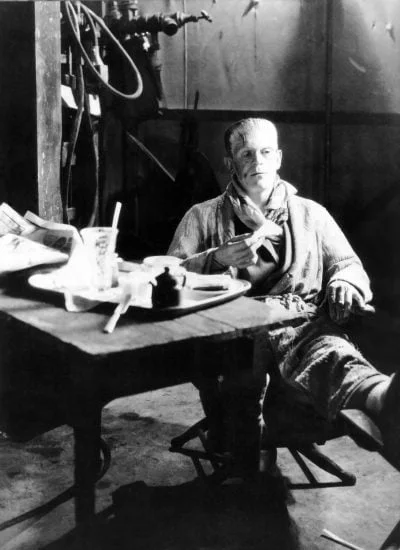

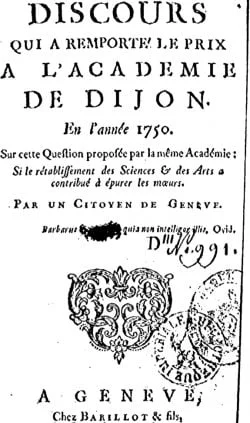

In this short story, Neeman weaves strands of text – anchored by footnotes – from works by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts” (1750) and “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality” (1755); novelist Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818); poet and essayist Percy Bysshe Shelley, “A Defence of Poetry” (1840); and novelist J.M. Coetzee, The Lives of Animals (1999).

In this short story, Neeman weaves strands of text – anchored by footnotes – from works by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts” (1750) and “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality” (1755); novelist Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818); poet and essayist Percy Bysshe Shelley, “A Defence of Poetry” (1840); and novelist J.M. Coetzee, The Lives of Animals (1999).

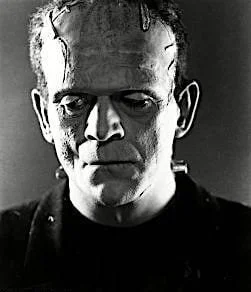

The main characters are Elizabeth Costello, from Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals; and Victor Frankenstein’s humanoid, known to Mary Shelley as the Creature, and now known simply as Frankenstein.

A note about the footnotes: in order not to interrupt the flow of the story, all quotations are italicized and marked with a footnote. When the characters in the story use quotes from other thinkers, these are also italicized and marked with a footnote. – Ed.

*

Passionately reasoning about the meaning of life

Passionately reasoning about the meaning of life

They are not yet on the expressway. He pulls the car over, switches off the engine, takes his mother in his arms. He inhales the smell of cold cream, of old flesh.“There, there,” he whispers in her ear. “There, there. It will soon be over.”[1] They have never been a demonstrative family[2] and as his mother, Elizabeth, stiffens in his arms he wonders what has come over him and her, with her tearful face turned towards him. Now that this moment of unacknowledged emotions is over, they murmur their goodbyes without looking at each other at the airport, as he loads her suitcase onto the baggage carrier. He is back in the car and on his way, his mother’s white hair and stooped shoulders[3]only a shrinking reflection in his rearview mirror.

Left with her suitcase, the expressway in front of her, and the airport terminal behind her, Elizabeth Costello the novelist,[4] ponders for just a while longer. She then turns to face the mountain range on her left and, leaving her suitcase behind, starts walking with measured steps. The setting sun is but a few steps ahead of her in the long trek towards the hidden side of the mountain. She squints a little as the late afternoon light assaults her eyes rather than guides her way. It is not long before the sun disappears and the weather changes, as dark clouds roll in and a cold breeze mocks her old flesh through the thin fabric of her blouse. She sits herself upon a rock with some effort and hugs herself with her flabby arms.

Left with her suitcase, the expressway in front of her, and the airport terminal behind her, Elizabeth Costello the novelist,[4] ponders for just a while longer. She then turns to face the mountain range on her left and, leaving her suitcase behind, starts walking with measured steps. The setting sun is but a few steps ahead of her in the long trek towards the hidden side of the mountain. She squints a little as the late afternoon light assaults her eyes rather than guides her way. It is not long before the sun disappears and the weather changes, as dark clouds roll in and a cold breeze mocks her old flesh through the thin fabric of her blouse. She sits herself upon a rock with some effort and hugs herself with her flabby arms.

When she feels her back warmed by coarse fabric resting against it, she thinks she may have fallen asleep and is dreaming. But when a strong rank scent fills her nostrils, she realizes that she is awake and turns around slowly. It is with the last dying light of the day that she sees a creature she has never seen before, not a human, not an animal, and as the incomprehensible in-between, not a pretty sight to behold. Her heart does not miss a beat when she says with a tired voice, “Hello, I did not realize that together with all the other miseries, you have also been bestowed with immortality.”

“You know who I am and yet you do not recoil from me,” the sentient being replies.

“Frankenstein’s creature,” Elizabeth sighs. “Humanity has come a long way since your creation.” She then adds softly, “It has… and yet it hasn’t”

“I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend,”[5] says the creature and his voice trembles.

“I know,” she murmurs in reply, “I know.”

As the creature settles on the rock beside her, the moon comes out from behind the cloud and they look at each other. There is no surprise in the eyes of either, but soft recognition and sympathy.

“So what have you been doing with yourself all these years?” she asks.

“I have been enjoying the most singular gift the human race has ever given me. I have been reading books. Many, many books! It is my sole way of conversing with humanity.”

“Oh” she says, “and what are you reading at the moment?”

“Oh, I have gone back to my all-time favourite, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the first thinker to express some faith in the innate virtue of human beings; although, mind you, I am yet to experience this goodness.”

“One is not obliged to make a man a philosopher before making him a man,” she recites from memory, “as long as he does not resist the inner impulse of compassion, he will never harm another man or even another sentient being.”[6]

“I see that you are well versed in Rousseau’s writing,” says the creature. “I am a sentient being and yet have been harmed many a time by evil, as well as by virtuous men and women.”

“Rousseau would suggest it is human reason that has brought us to define ourselves apart from others, both within and outside of human society,” Elizabeth replies. “When he writes that ‘in other lands idle men spent their lives debating about the sovereign good, about vice and about virtue; and [that] arrogant reasoners, bestowing on themselves the highest praises, grouped other peoples under the contemptuous name of barbarians,’[7] he indicates that reason is at the root of our alienation from others, be it barbarians, creatures, or animals. I don’t think he saw reason as the highest faculty of mankind, as did some of his predecessors.”

“Yes,” says the creature scratching his enormous blistered chin, “he believed that man started with passions originating from needs, and that it is only in the social context that reason came to play a role. This is different than Rene Descartes, who saw reason as the first pillar of human existence. For Rousseau, free will, desire, and fear are the first and only operations in the savage man’s soul.” The creature then quotes, emphatically: It is impossible to conceive why someone who had neither desires nor fears would go to the bother of reasoning.[8]

“Well, I definitely agree with him on that,” says Elizabeth Costello. “This ‘Cogito ergo sum’ of Descartes leaves us as a ghostly reasoning machine thinking thoughts. It has an empty feel to it: the feel of a pea rattling around in a shell.[9] I do not identify my existence with such a notion. It is the heavily effective sensation of being a body, of being alive to the world which is the fullness of being.[10] Seeing being as such, allows the respectful inclusion of other animals in our definition of existence.”

He lifts his heavy eyelids and looks at her through surprised yellow eyes. “You care a lot about animals, don’t you? I thought human beings merely used animals as food, pets, and for science. You seem different.”

“I am different all right,” she says quietly. “I vehemently believe in animal rights and cannot live with the cruelty that we, as a human society, commit against them. I look into other people’s eyes and I see only human kindness. Calm down, I tell myself, you are making a mountain out of a molehill. This is life. Everyone else comes to terms with it, why can’t you? Why can’t you?”[11]

“I am vegetarian!” cries the creature happily clapping his hands, “I have taught myself to make the most delicious root-stew and berry-mush! In fact, I have some of both with me right here and it is dinnertime. Would you share a meal with me? My cave is right around the corner. It is nice and warm with my fire in there.”

She nods, while raising her tired body and wrapping herself in his long thick coat. Following his nimble steps, she feels a new sense of liveliness and connection that surprises her. As they enter a small cave, she instantly feels the pleasant warmth of a fire. Responding to his hesitant invitation to sit, she lowers herself to the ground and looks around curiously. It does not take long before both creature and old lady are hunched around a steaming pot hungrily slurping its content.

“This is very good!” says Elizabeth. “Thank you for your kindness.”

“Thank you,” replies the creature. “It is nice to be recognized. For a long time my heart [has] yearned to be known and loved … I required kindness and sympathy.[12]

“Being loved and happy is the right of every sentient being!” She says emphatically.

“I agree,” replies the creature. “Rousseau, though, was suspicious about love. He saw it as an artificial sentiment born of social custom and asserted that ‘love itself, like all other passions, had acquired only in society that impetuous ardour which so often makes it lethal to men’”[13] the creature quoted enthusiastically as he dribbled some of the orange stew on his tattered shirt.

“Yes, for him there were really two kinds of passions, weren’t there?” says Elizabeth dreamily. “The original ones, related to the instinctive virtue of man, and the secondary ones, which are the outcome of living within human society and with inequality. Rousseau says that, “consuming ambitions, the zeal for raising the relative level of this fortune, less out of real need than in order to put himself above others, inspire in all men a wicked tendency to harm one another.”[14] And he concludes that, “the less natural and pressing the needs, the more passions increase and, what is worse, the power to satisfy them…Passions have forever destroyed their original simplicity.”[15]

He nods in agreement.

“You know,” she adds, gently tapping her wooden spoon against the side of the pot, “I don’t think Rousseau realized how far these zealous consuming ambitions would end up driving human society. He thought about the social impact this tendency would have. But nowadays, this zeal is also having a devastating environmental impact!”

“He may not have anticipated this particular impact, but he did reflect about the arrogance of knowledge and the danger in it,” the creature says. “He admired Socrates’ praise of ignorance, and said, ‘a god who was antagonistic toward the tranquility of men was the inventor of the sciences.’”[16]

“I know,” she mutters. “And now we admire those mediocre academics and measure the distance from that same god by knowledge of academic Mathematics.”[17]

The creature suddenly jumps off his hunches, banging his bald skull against the ceiling of the cave. “One of my favourite writers is Percy Shelley. I know he was quite a character and took advantage of the people closest to him, but as I never had a relationship with him, I don’t really care. He wrote, “The cultivation of those sciences which have enlarged the limits of the empire of man over the external world, has, for want of the poetical faculty, proportionally circumscribed those of the internal world; and man, having enslaved the elements, remains himself a slave.”[18] This really resonates with me. I for one, certainly feel that my creator was a poetically deprived scientist, whom I enjoy thinking of as a slave!” He says this with a grin.

“Yes, and he definitely did not assume the responsibility he had towards you as your creator, did he?” says Elizabeth, tenderly looking at him. “This issue of responsibility and knowledge bothers me. When I think of Germans of a particular generation, I find, they lost their humanity in our eyes, because of a certain willed ignorance on their part. I do believe that the psyche (or soul) touched with guilty knowledge cannot be well[19] is true for your creator as well as others.”

“Hmm indeed, my creator himself said, “how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.”[20] The miserable wretch! He was the architect of his own misery… and mine,” he adds pensively. “But you must be tired. You had a long day. Would you honour me and stay the night in my humble cave? I can spread my coat for you and keep my fire going.”

She looks up at him, smiles warmly and nods, “The honour will be all mine”

It does not take long before the two are stretched supine on both sides of the fire, looking up at the shadows dancing on the ceiling.

“You know,” he says, “It is interesting how as soon as I had learnt human language, I became obsessed with unrelenting thoughts. Who was I? What was I? Whence did I come? What was my destination?[21] It has been almost two hundred years now. I have read numerous books and I continue to be plagued by those same questions.

“You must be human after all,” she says with a smile, then turns on her side and closes her tired eyes.

*

Havi Neeman graduated from Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University in 2015. She wrote this short story in Stephen Daguid’s seminar, “Reason and Passion,” at the end of her first GLS semester, when she found that the characters from her readings were no longer bound to the pages. Havi loves to read and is passionate about the outdoors.

Havi Neeman graduated from Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University in 2015. She wrote this short story in Stephen Daguid’s seminar, “Reason and Passion,” at the end of her first GLS semester, when she found that the characters from her readings were no longer bound to the pages. Havi loves to read and is passionate about the outdoors.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] J.M. Coetzee, The Lives of Animals (Princeton University Press, 2001) [1999], p. 69

[2] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, p. 15

[3] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, p. 15

[4] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, p. 15

[5] Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus (Penguin Classics, 2003) [1818], p. 78

[6] J.J. Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality” [1755] in Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Basic Political Writings. Ed. Donald A. Cress. Hackett Publishing Company, 1987, pp. 25-109; p. 35

[7] J.J. Rousseau, “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts” [1750], in Jean-Jacques Rousseau The Basic Political Writings. Ed. Donald A. Cress. Hackett Publishing Company, 1987; pp. 1-21, p. 7

Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality,” p. 46

[9] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, p. 33

[10] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, p. 33

[11] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, p. 69

[12] Shelley, Frankenstein, p. 107

[13] Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality,” p. 56

[14] Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality,” p. 68

[15] Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin of Inequality,” pp. 91, 94

[16] Rousseau, “Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts,” p. 10

[17] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, p. 24

[18] P.B. Shelley, “A Defence of Poetry.” A Defence of Poetry and Other Essays. Dodo Press, 2007 [1840]. pp. 43-70; p. 64

[19] Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, pp. 20, 21

[20] Shelley, Frankenstein, p. 35

[21] Shelley, Frankenstein, p. 104