#821 The hidden pulse of Vancouver

Rain City: Vancouver Reflections

by John Moore

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2020

$20.00 / 9781772141399

Reviewed by Grahame Ware

*

On the inside front pages of Rain City: Vancouver Reflections, John Moore brandishes a quote from Paul St. Pierre: “A journalist is a reporter who can’t hold a steady job.”

On the inside front pages of Rain City: Vancouver Reflections, John Moore brandishes a quote from Paul St. Pierre: “A journalist is a reporter who can’t hold a steady job.”

The instability of journalism and feature writing has left its scars on many freelancers. A hard-working Vancouver journalist, Moore has been gutting it out for the last thirty or forty years in a variety of activities as the Grim Reaper of underemployment hovered alongside the Seductive Siren of journalism. Invariably, Moore has had to do a lot of freelance work just to keep the wolf from the door.

Seemingly, Moore is one of those inexorable optimists who motor on and, after dealing with all of the disappointments, comes up with quips and zingers that would bring a broad smirk from even the most blithely cynical comedian. But despite scuffing along, Moore is a lot like patent leather. Give him a quick wipe and he shines, always sounding and looking brightly polished.

Like many a working class lad, Moore had enough belief in himself to work hard at his craft and overcome obstacles through his energy and emergency planning. In short, he was never outworked. Moore draws on all this material in Rain City, reflections on his unvarnished Vancouver.

Despite the delays in getting Rain City onto the market, the book remains remarkably understated. For nearly a year the book hung in pre-publication purgatory with its debut pushed back due to the problems of its publisher, Anvil Press. Anvil had to move twice during this time, and due to the physics of moving and loss of editing time, things went sideways. This is Moore’s first book with them. Despite the delays, there was no rush to include raves on the back cover or inside jacket from marquee names like so many books do these days; no spots with Squire Barnes on Global News nor plugs on CBC cultural affairs programs. Nothing but the delays. However inauspicious its arrival, the little blue covered paperback that you can tuck into your pocket and read a piece at a time has been worth the wait. And, oh what stories these be!

Moore was a well-known writer for the Vancouver Sun, where for the better part of 20 years (1983-2003), he provided readers with some of the snappiest and least crappy reviewing. His reviews were like shots of Drambuie compared to the lukewarm Ovaltine of others on staff.

Quaff this little taste of his reviewing style: in his recent piece entitled “Escape From The Fish Farm,” of a biography by Ian Cutler, Jim Christy: A Vagabond Life (2019) in The Ormsby Review (no. 596, August 26, 2019), Moore observes that “Christy is a wild Steelhead in a Canadian literary seascape choked with schools of writers spawned in university creative writing departments operating like fish farms.”[1]

But Moore’s gig as a reviewer at the Sun ended in about 2003 with budgets cuts. The neutering of personalities and ideas at the paper had started in corporate earnest with its takeover by Conrad Black’s Hollinger Corp in 1996. Lord Black of BlatherTwaddle Manor then flipped it four years later to Izzy Asper’s over-leveraged Canwest which, nine years later, went into creditor protection. What the Southams had built up over a century, the Aspers destroyed in less than a decade. Gone were the columnists and personalities with their wit and highly tuned BS radars that gave readers a reason to buy the newspaper.[2]

But as history and time have amply demonstrated, the reviewer as a species was as endangered in its cultural ecology as the orcas of the Salish Sea. In fact, the loss of cultural biodiversity is not just a local problem but a global issue as Big Media and the hegemons of corporatism pursue a scorched earth, “poison their wells” policy popularized by the Romans some 2,000 years ago. Newspapers are no longer a cultural nest from which eager new fledglings of journalism take flight.

However, Moore’s life as a reviewer didn’t end with the downsizing of the Sun. After the axe fell, he did a little reviewing for The Globe and Mail and Tyee. Alan Twigg twisted his arm to review for BC Bookworld and Moore agreed, becoming a much-needed critic for the quarterly newspaper. Thus, his life as a reviewer continued while he worked for newspapers, trade magazines, and Bookworld.

Understandably, Moore is beyond wistful when reflecting on those freelancing salad days, especially at the Sun with its “Saturday Review” supplement, edited by Max Wyman and Carol Toller. In an April 2020 email he reflected to me:

Those were great times and I find it tragic that journalism has become a pathetic shadow of itself. That’s part of my reason for wanting some of these essays [in Rain City] to be saved from entombment in the morgues of defunct newspapers who no longer have the courage to employ such editors or take such risks. Newspapers have mostly abandoned the field to every low-watt bulb who can scoop enough out of the change jar to buy a domain name, become a blogger and rant to his or her illiterate heart’s content.

*

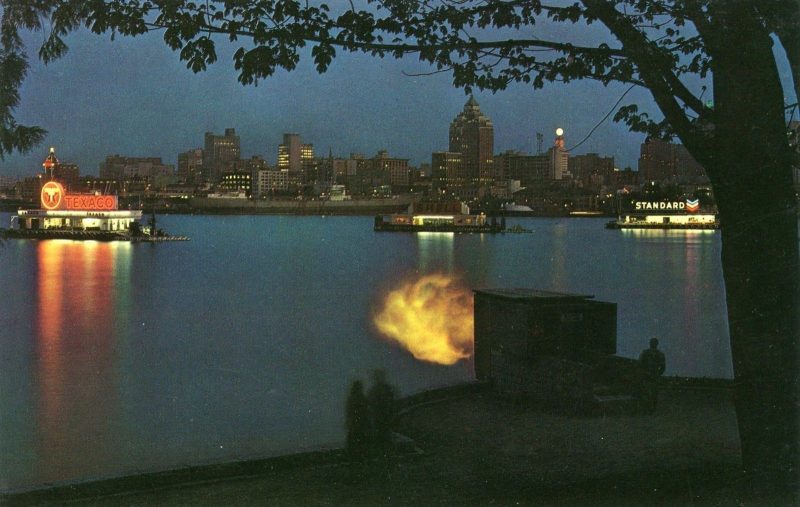

Moore’s Rain City has a number of different elements, styles, and themes, with the bulk of these stories having first seen the publishing light in subTerrain magazine, the magazine arm of Brian Kaufman’s Anvil Press, and the Vancouver Review, which is no longer a print magazine but a video-schmideo thingummy. However, it is apparent that Moore’s pieces have been re-drafted and “improved.” Moore’s journalistic essays in Rain City are, at times, like an emergency flare shot not from a handgun but the cannon of the 9 O’Clock Gun. His journalism resembles an explosive and mesmerizing arc, leaving an incandescent hieroglyph pasted against a clear night sky, not unlike one of those Vancouver nights after the rain has blown away the heaviness, dust, and the skenk of man. The air at that moment, like his writing, is crisp and fresh and totally Vancouver. But the vapour trail of his critical reviewing has left a worthwhile legacy on the west coast skyline.

There are some very good memoir pieces here, alongside the journalism. Using the organic template of his life, Moore has distilled his life’s emotions and events. For me, he is at his best in the memoir mode. Like a high-twitch colt in a stable of Percherons, once released to the open field, he relishes his speed and later, in a nod of the mane to his clan, his stamina. It’s obvious from his early writing and his memoirs that he would not easily be broken. He still snorts coltishly in his Squamish corral.

My favourites in Rain City are three of the memoir pieces: “Imaginary Geography,” “Finding My Marbles,” and “A 29 Hand.”

In the first, Moore recounts his boyhood sense of place in North Vancouver, in a newly carved-from-forest subdivision along Mosquito Creek (a river by any other world standards). Moore describes how it was “a small but still wild river,” with:

[H]uge boulders, eight to ten feet across [that] formed natural dams, restraining terraced pools of crystal water of equal depth. Shaded by drooping boughs, these were the swimming holes of nymphs, dryads and oreads, drinking fountains of the gods and home to trout of twelve to twenty inches…sacred places where we spent all our unsupervised time exploring the channels and small islands…. (p. 56).

This is the writing of a child in love with the wonderfully primeval splendour of his bucolic backyard. For many of us growing up in Vancouver and environs in the fifties, this was the normal before in-fill urbanization stamped it with a much more sterile environment that depended on the amulets of affluence — cars and the paraphernalia that automobiles require — as hollow replacements for the stirring, natural beauty of the un-filled, wooded suburbia of Greater Vancouver. But nothing now could, or will, ever replace it.

“The creek was the hidden pulse of the neighbourhood,” Moore writes, but floods caused by the cyclone of 1963 meant the creek was “dynamited and bulldozed into an innocuous ditch…. Overnight, it became ugly and dull, the mid-channel islands of firs and cedars that sheltered our forts gone as if they’d been hit with a tactical nuclear bomb. With it silenced, we became part of the vast, tame suburbs of Vancouver’s North Shore” (p. 65).

The ecological insensitivity of this by-product of disaster capitalism and suburbanization also meant an emotional loss for Moore. Mosquito Creek, a sacred artery he’d known and loved, was gone, thanks to the public works department’s wish to “protect the incipient upper middle class from having their real estate values literally eroded” (p. 65).

In Finding My Marbles, Moore tells us about the value and importance of marbles (and their games) in the kid culture in the fifties in Vancouver. He does it like no one has ever done:

In the 1950s, marbles were still seen by the adult world as a quaint detail of a Norman Rockwell illustration, the harmless pastime of boys in knickerbockers; a relic of a simpler time. School officials sensed marble season was an infinitely more complex social phenomenon than it appeared, but they couldn’t penetrate its mysteries any more than an undergraduate anthropologist could wrangle an invitation to a genuine voodoo ceremony (pp. 134-5).

There is so much description here of “the child’s casino” and the “alley mercantile,” all of it funny and illuminating without any sentimental treacle or noise. Truly, this is a terrific memoir-essay of postwar Vancouver that social historians of BC should put right on their university reading lists.

In “A 29 Hand,” Moore digs into his family vault and goes deeper and further emotionally. The story revolves around the game of cribbage with some lovely tie-ins to its history both recent and ancient. However, the really outstanding part involves him and his grandmother, whom he labels “the cribbage bitch.” Moore is not being cruel here, just truthful to his early perceptions. It was she that taught him the game as his “kindly Nan,” but once taught, “With cards rippling in knitting hardened hands, she ceased to be Nan and became an implacable nemesis,” as she morphed into the cribbage bitch. She was going to take you down gleefully every time she could.

Making matters worse was that she moved back into Moore’s house, with the passing of his father when Moore was 13, and assumed the role of Matriarch in the household. Once ensconced,

She infantilized my mother and manipulated me and my brothers and sister by emotional bullying as ruthless as her crib playing, rewarding obedience with affectionate spoiling and rebellion with merciless sarcastic persecution. [And] if you called her bluff when she made cutting remarks about your clothes, hair or friends, she played the Grandmother card and burst into tears of misunderstood altruism. It was like being trapped in the Actors Studio with Bea Arthur on crystal meth (p. 214).

This was the revenge of an over-functioning and under-loved woman, the dénouement of her role as the recycled Mum and Golden Girl, seen here by Moore in a bitter sunset. Such is the scope and delightful imagery and minutiae of Moore’s writing that one’s attention rarely wanders.

*

Rain City shows us many writerly aspects. First, Moore as a curious literary rock hound who wanders into caves and hammers at the walls with his Estwing hammer looking for glints of light in the trapped crystals of dark, cavernous rock. Second, he turns into a lapidary of words and concepts, polishing them in the rock washer of his mind and giving them enough tumbling and drafting, always careful to add the proper grit they need to really shine. A literary lapidary, Moore gives us stones that come out looking as fascinatingly lustrous as a King Cob marble. This is what delights in Rain City. I suspect there are other deep emotional veins still to be processed here in his caverns, and I hope he’ll keep hammering away.

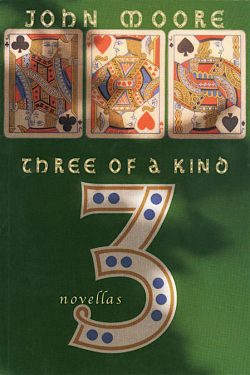

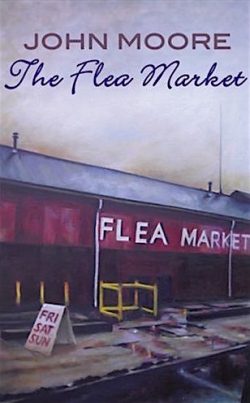

Being a noted and popular reviewer may have had the unintended consequence of being taken for granted as a writer, but Moore’s subsequent writing career certainly took care of that issue. No longer the Sun’s literary reviewer, he really hit his stride as a writer with the publication of his trio of novellas, Three of a Kind, published in 2001 by Ekstasis just as the sun was setting on his reviewing gig at the Sun. The three short novellas included (as one volume) in Three of a Kind are Castro’s Paperboy, Saturday Soldiers, and Code II. Moore also wrote The Flea Market for Ekstasis (2003).

The Peter Trower connection: Moore as an emerging writer

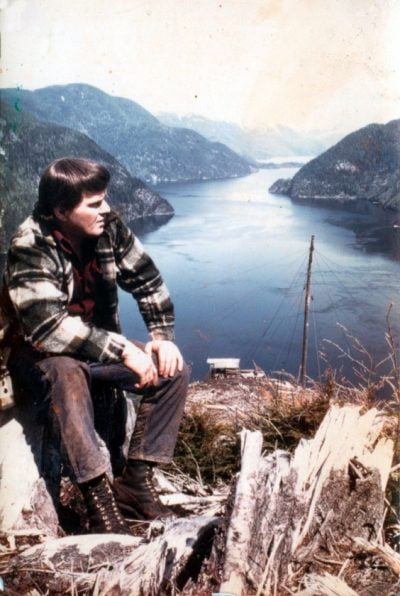

Having tried to be a poet when he started out writing (see his New Moon & Money, Harbour, 1983), Moore eventually realized this was not his literary vehicle. In this conclusion, he was not alone. His launch as a poet and writer took place when he was working for Sunshine Cabs. “I met Trower in Gibsons in ’78 or ’79,” he relates in a recent email, “when I was driving cab on the Sunshine Coast on weekends to help out a friend who’d just bought the taxi company. I brought home this little chatty old lady from the grocery store.” This would be Trower’s mother, Mary Cassin, “a strange birdlike little creature who painted and wrote all her life. Her father had been Governor of Malaya. She was very well educated and a riot to talk to.”

Trower, who grew up in Port Mellon and nearby Gibson’s Landing, was living at this point with his mother in a tiny house on the bay:

[It] looked like it might float off in a high tide. I had the most wonderful conversation with her. She was impressed that I had read the ancient Chinese text The Art of Tea and we rabbited on at some length. Just as I was leaving, a guy came out of this shed/garage that appeared to be sinking into the weeds surrounding it, wearing loggers’ stagged jeans, caulk boots, with a cap pulled down over his brow and a very mean look on his face.

“You got my vodka?” he snarled. “I called two hours ago for a bottle of Smirnoff.” I confessed I did not have his vodka while appreciating the bush-ape stance, hunched, arms slightly out from the compact body, lookin’ ready to get some, as they say. I immediately volunteered to call the office and see if I could run his errand before taking any more trips. “Alright then, c’mon in the shack.”

Inside, the walls and ceiling were entirely papered over with posters from the Be-ins and Love-ins and Trips Festivals of the 60s. Piles of books teetered everywhere. In front of a sprung couch, on an old coffee table, perched a small Brother typewriter with a page hanging out, covered with eccentric lines I recognized immediately.

“You’re a poet.” I said.

“Damn right I’m a fuckin’ poet. Been published in Poetry Chicago. McClelland & Stewart are publishing my selected poems, Ragged Horizons, this year.”

Then he handed me some pages of poems to read, but first he made me call about the vodka. The cab dispatcher knew Pete well. They told me to go get his booze right away. He lifted the poems from my hand. “You can read ’em when you get back.”

My memory of the rest of that afternoon is a little fuzzy, since the moment I returned with a Texas Mickey of vodka I sat down and started reading one really great poem after another and talking with this incredible dude, while helping him put a dent in the vodka. Hours later I called the cab company to explain that I had become “indisposed.” They were very understanding and sent somebody to pick up the cab, and me.

Pete introduced me to his friend John Burnside, editor of the local paper, the Coast News, a haywire journal barely a step above being an underground newspaper. In no time I was writing a column on books, then working for them as a reporter. Before I met Pete, I was trying to write poetry and fiction, but had no idea whether it was any good or how to get into print. But a few years later, Howie White, another old pal of Pete’s, published my first (and only) collection of poems, New Moon & Money (1983) By then, I’d started reviewing for the Sun and was branching out. In fact, the very first book I reviewed for the Sun was Trower’s Ragged Horizons.”

Talk about synchronicity. Moore’s arc as a writer was indelibly stamped by his timely meeting and subsequent relationship with Trower. As Moore continues,

Looking back, I see that his effect on my life has been immeasurable. Besides reviews, I wrote a number of features about him for the Sun and other papers when he published new work. I was always glad to pay down some of the interest on my debt to him. Through him I met people like Howie White, the late George Payerle, Jim Christy, Mac Parry, and all sorts of writers and rounders. Even the owner of the bookstore in Squamish turned out to be an old friend of Pete’s.

Trower’s at the nexus of a lot of connections in my life. My father died when I was barely 13. I wouldn’t say I looked on him as a father-figure, certainly not as a role-model, but there was something of that in our relationship, even when we argued. I think Pete regarded me as a kind of younger version of himself, an autodidact and mostly self-taught writer that he could help. I was not alone. He helped so many young Vancouver writers who hung around his table in the Alcazar pub and later at the Railway Club.

And Moore remembers his own early years:

My mother used to bring home stacks of very strange books from the N. Van library and I got in the habit of reading her books when I was young. She was always tracking me down, looking for a book she’d been reading and I’d picked up and made off with. I think I read Sartre’s La Nausée when I was 13 or 14 out of one of her stacks. If she didn’t like a book, she would almost always pass it on to me to find out what I thought of it. I always found that one book, or even a review that compares the author to another author, leads on to other books, as if each book was a clue in a scavenger hunt, which is probably an accurate description of my approach to education. In my 20s I read mostly European writers. I preferred Camus and Kafka above all (one of literature’s greatest comedians) then Samuel Beckett, Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs. I loved to read and read everything I could get my hands on, lots of great pulp fiction as well. I liked unpretentious humorists like Jean Shepherd, the English writer Leslie Thomas and of course Peter de Vries.

My mother used to bring home stacks of very strange books from the N. Van library and I got in the habit of reading her books when I was young. She was always tracking me down, looking for a book she’d been reading and I’d picked up and made off with. I think I read Sartre’s La Nausée when I was 13 or 14 out of one of her stacks. If she didn’t like a book, she would almost always pass it on to me to find out what I thought of it. I always found that one book, or even a review that compares the author to another author, leads on to other books, as if each book was a clue in a scavenger hunt, which is probably an accurate description of my approach to education. In my 20s I read mostly European writers. I preferred Camus and Kafka above all (one of literature’s greatest comedians) then Samuel Beckett, Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs. I loved to read and read everything I could get my hands on, lots of great pulp fiction as well. I liked unpretentious humorists like Jean Shepherd, the English writer Leslie Thomas and of course Peter de Vries.

I also read a lot of poetry; first, Yeats and Dylan Thomas (whose work I didn’t understand in my early teens, but now whose words still affect me like religious liturgies), then a lot of Beat poetry (the usual suspects), Gwendolyn MacEwan, who I thought was wonderful as I read it in a bookstore one afternoon. Of course, Eliot and Pound at university, though I preferred Wallace Stevens and Hart Crane.

One of my favourite local poets was a guy called Norm Sibum, who lived out here for a while driving cab. Eventually Sibum moved back east to Montreal.[4]

From Newbie Poet To Critic

Many, if not all, of the best writers realize sooner or later that poetry is just a literary signpost on the road of life. Stan Persky, for example, recalled in Autobiography of a Tattoo (New Star, 1997, p. 111) that although he’d found his voice in poetry, “I eventually saw that [my voice] was better suited to writing than poetry.” Something similar could be said of Peggy Atwood, Anne Michaels (especially her magnificent novel, The Winter Vault (McClelland & Stewart, 2009), and Michael Ondaatje. Fortunately for us, Moore came to that realization as well.

Many, if not all, of the best writers realize sooner or later that poetry is just a literary signpost on the road of life. Stan Persky, for example, recalled in Autobiography of a Tattoo (New Star, 1997, p. 111) that although he’d found his voice in poetry, “I eventually saw that [my voice] was better suited to writing than poetry.” Something similar could be said of Peggy Atwood, Anne Michaels (especially her magnificent novel, The Winter Vault (McClelland & Stewart, 2009), and Michael Ondaatje. Fortunately for us, Moore came to that realization as well.

Those who stay locked in the Poets Ward often require shock therapy to wean them off their drugs of precious literary swagger. But like Jack Nicholson’s character in Milos Foreman’s film, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, Moore would rather risk having a lobotomy than stand by and watch the passive-aggressive BS play itself out in the local literary scene. Not only was Moore the arbiter of the local literati (along with the excellent reviewer George Fetherling), but also the assassin. It was in his very important role as reviewer and critic that Moore really found his literary groove.

In this sense he joined a distinguished group that includes – just to hit on the really big ones — the likes of John Lahr, Louis Dudek, Nat Hentoff, Lionel Trilling, Robert Hughes, Frank Kermode, and the recently deceased Harold Bloom. What distinguished them is that they weren’t just critics — they were writers who had a very important impact on critical opinion in English-speaking culture and they were also, in fact, also creative forces in their own right.

Despite the disparaging cautionary wisdom of Brendan Behan, the notorious Irish drunk and writer who said, “Critics are like eunuchs in a harem: They know how it’s done, they’ve seen it done every day, but they’re unable to do it themselves,” Moore and his clan are not merely gabby because they are nutless. Far from it. Critics, more so than ever, are absolutely required reading in our culture.

The counter to that bit of scurrilous Behan bombast comes from Virgil Thomson, the famous composer, who struck a definition of criticism as “the only antidote we have to paid publicity.” In “The Fate of the Critic in the Clickbait Age,” Alex Ross in the New Yorker avers that “Criticism of any kind is increasingly unwelcome at the digital-age paper:”

In a cultural-Darwinist world where only the buzziest survive, the Arts section would consist solely of superhero-movie reviews, TV-show recaps, and instant-reaction think pieces about pop superstars. Never mind that such entities hardly need the publicity, having achieved market saturation through social media. It’s the intellectual equivalent of a tax cut for the super-rich.

Moore has done some extraordinarily creative work as a local critic, his reductive effervescence always a tonic for jaded readers. And if you have any doubts about his ability as a reviewer, you only have to sample reviews by well-known poets or novelists to see how dull they are by comparison. The exceptions in my opinion are Brian Fawcett, Moore’s Dooney’s Café buddy Stan Persky, and Susan Musgrave. However, the macroeconomics of our literary culture have worked not only against Moore but species like him around the globe these past few decades.

Moore’s review in BC Bookworld (September 2016) of Peter Babiak’s Garage Criticism (Anvil, 2016) was particularly insightful in that he was reviewing a reviewer, social critic, and post-secondary English teacher. The results are instructive:

In his Garage Criticism, Babiak does what smart people are supposed to do — question the real meaning and implications of elements of the larger culture that permeates our lives and to a large extent determines who we are, with or without our permission or connivance. Babiak dares to address popular culture in language it can understand. Colloquial and relentlessly funny, Babiak uses personal anecdotal hooks to draw the reader to more serious issues. His academic colleagues will probably scorn him for interdisciplinary cross-dressing or “dumbing down The Discourse.”

I remember being very disillusioned at meeting many Very Smart People at UBC in the early Seventies and seeing all this insight and intellectual brilliance deliberately hidden behind masks of discipline-specific critical jargon concocted to exclude non-speakers from participating in “the discourse.”

At a time when our culture is … so easily manipulated by political and corporate interests, we desperately need critics who aren’t afraid to call The Discourse (merely) a SnapChat.

Ah yes, the aforementioned fish farms of creative writing departments. Moore definitely did not spring from that hatchery and is unlikely ever to eat processed fishmeal, preferring what the sea itself provides: the plankton and krill of everyday life. Moore is not wowed by posture, fetish, or clumsy adornment. He looks right through it and isn’t afraid to tell it like it is in his own stylish, Moore-ish way.

*

Grahame Ware is known for his essays, book reviews, and popular memoirs of Vancouver in the 1950s and 1960s: “My Private Chinatown” (The Ormsby Review no. 501, April 2, 2019) and “My Private Italy” (The Ormsby Review no. 530, May 17, 2019). An avid gardener, he is author of Heucheras and Heucherellas: Coral Bells and Foamy Bells (Timber Press, 2005, with Dan Heims), and he has contributed articles to the International Rock Gardener, The Rock Garden, and The Plantsman. See Phantasma Sculptura for his wood sculpture and related subjects. Grahame lives on Gabriola Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Culture critic Elif Batuman would agree with Moore on this point. See his “Get a Real Degree” September 23, 2010, London Review of Books.

[2] The Sun was especially decimated due to its non-Centrist Canadian point of view. Asper’s irresponsible ventures into the Canadian newspaper industry resulted in the main newspaper assets being sold to a New York hedge fund, Golden Tree Asset Management, in 2010. They created the aptly and ironically named Post Media News. Eight horrible years later, the cultural identity wasteland created by this takeover was again taken over — this time it was Chatham Asset Management, a conglomerate that owns American Media Corporation. Yankee continentalism had completed its greatest coup as this Republican Party based-outfit (that owns David Pecker’s National Enquirer) now controlled the Canadian newspaper landscape. Thanks, Izzy! Now there was just a token janitor/writer or two to keep the edifice and artifice of the Vancouver Sun from gathering too much dust as they pivoted from one investment disaster to another while throwing their junk bonds into the shredder to make confetti for the Postmedia parade.

[3] Silbum recently wrote his first novel, The Traymore Rooms (Biblioasis, 2013) to critical acclaim. “It isn’t so much a dip of his toe into the world of fiction as a cannonball off a third-storey hotel balcony.” Michael Hingston, National Post, August 23, 2013.

5 comments on “#821 The hidden pulse of Vancouver”

Thank you so much for those kind comments.

World class review – thoroughly comprehensive and all encompassing.