#797 Secwépemc land and language

Clinging to Bone

by Garry Gottfriedson

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2019

$17.95 / 9781553805625

Reviewed by Heather Simeney MacLeod

*

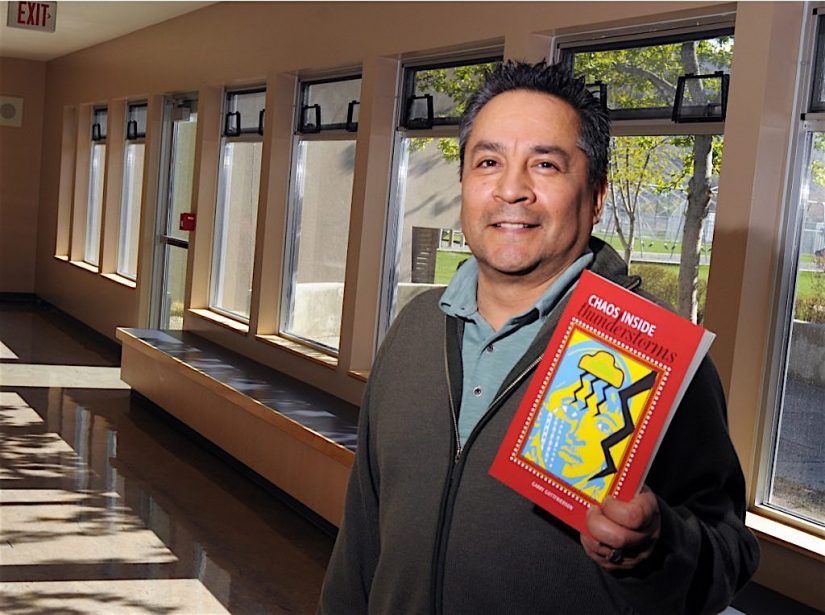

Garry Gottfriedson is from the Secwépemc (previously Shuswap) Nation. He was born, raised and continues to reside in Kamloops. He studied under Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, and Marianne Faithful at the distinguished Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, where he obtained his MFA in Creative Writing. He also has a Masters in Education from Simon Fraser University. Besides his work as a rancher and professional breeder of horses (fourth generation), he has been a teacher at the primary and secondary levels, worked as a school principal, served as a councillor and consultant for the Kamloops Indian Band, and published nine books including the collaborative In Honour of Our Grandmothers: Imprints of Cultural Survival (Theytus Books, 1994), with George Littlechild and Reisa Smiley Schneider, among others. He is from a locally-renowned ranching and rodeo family — yes, those Gottfriedsons. Besides the family’s prominent ranching pedigree, they are equally recognized for their immersion in and traditional knowledge of the Secwépemc people and, I would assert, for their generous and humble natures. Both attributes are readily seen in Gottfriedson’s most recent poetry collection, Clinging to Bone.

Garry Gottfriedson is from the Secwépemc (previously Shuswap) Nation. He was born, raised and continues to reside in Kamloops. He studied under Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, and Marianne Faithful at the distinguished Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, where he obtained his MFA in Creative Writing. He also has a Masters in Education from Simon Fraser University. Besides his work as a rancher and professional breeder of horses (fourth generation), he has been a teacher at the primary and secondary levels, worked as a school principal, served as a councillor and consultant for the Kamloops Indian Band, and published nine books including the collaborative In Honour of Our Grandmothers: Imprints of Cultural Survival (Theytus Books, 1994), with George Littlechild and Reisa Smiley Schneider, among others. He is from a locally-renowned ranching and rodeo family — yes, those Gottfriedsons. Besides the family’s prominent ranching pedigree, they are equally recognized for their immersion in and traditional knowledge of the Secwépemc people and, I would assert, for their generous and humble natures. Both attributes are readily seen in Gottfriedson’s most recent poetry collection, Clinging to Bone.

This collection is separated into five parts consisting of “This Holy Place,” “Exhumation,” “Clear Memory,” “My Voice,” and “Hunting Ground.” The first section centres upon the topography of Kamloops and extends to that of the Okanagan, Ottawa, and Yellowknife. Gottfriedson articulates his beginnings on his mother’s side in Kamloops and his father’s side from Vernon by way of Denmark. In “Exhumation,” the second section, Gottfriedson references the politics between the white settlers and the Indigenous peoples of Canada. He gestures towards residential schools, unceded territory, treaties, the behaviour of the Catholic church, and also — importantly — the role of pollution and climate change in the alteration of the land. “Clear Memory,” the third part, considers love and romance, not only between the speaker of the poems and another person, but also between him/herself and the land. The fourth section, “My Voice,” opens with the death of the speaker’s mother and moves through landscapes from Austria and Spain and into the United States. The final section, “Hunting Ground,” moves through a familiar terrain of restaurants, weather, and ranching communities familiar to most people from the interior of British Columbia. Overall, the sections carry topics over from previous ones, so the collection as a whole considers land, people, time, discord, and some of the history of this region’s Plateau people.

The first section introduces the complexity of the speaker of these poems. It opens with “This Holy Place” and sets in some ways the tone for Clinging to Bone: “I was born with songs / surging from my throat / swirling in the blood of my life-givers / tossing in the currents / of trickster stories / of my Secwépemc ancestors” (p. 3). These opening lines indicate so much of what the collection does, including the idea of words that must be spoken, that language is connected ancestrally and moves through the currents of the North and South Thompson Rivers, that the stories are of the speaker’s people, from his/her immediate family to his/her ancestors. These themes and concepts work like threads moving through the collection. In all these ways Gottfriedson relishes and takes pride in his place among the Secwépemc nation. The section closes with poems that look outside of the region of Kamloops to the Okanagan, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and into the Canadian arctic.

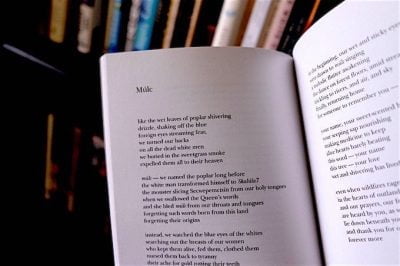

Gottfriedson’s second section, “Exhumation,” opens with the astounding “Téy — The Women’s Dance,” a beautiful piece revealing the relationship between the land of this region and its original occupants, and the work of women. For example, “butterfly floating over sweetgrass and moss / timber and lakes and rivers / hips telling the secrets of / bellies swelling, breasts full / delivering new layers of meaning / like water breaking” (p. 22). He deftly weaves people, language, traditions, family, community, and spirit not just to land but coming from it. “Exhumation” closes with “Múlc.” The two poems work as bookends to the section, but do more than just frame it; they function as a circular motion, with “Múlc” returning the reader to “Téy — The Women’s Dance.” In “Múlc,” the relationship between settlers and original inhabitants is exposed from its beginnings to its current incarnation. Gottfriedson doesn’t flinch: “the monster slicing Secwepemectsín from our holy tongues / when we swallowed the Queen’s words / and she bled múlc from our throats and tongues / forgetting such words born from the land / forgetting their origins” (p. 44).

Here, Gottfriedson reveals the incredibly deep relationship of language to land, which is perhaps something a non-Secwepemc person cannot fully comprehend. The language — Secwepemectsín — comes from the land. The land, as it appears here, gives birth to the Secwepemc people’s words, phrases, articulations, meanings, symbols, and metaphors. Múlc is Secwepemectsín for Black Cottonwood. According to Green Timbers Heritage Society, “It is the most important deciduous tree in B.C., and is heavily logged.” Gottfriedson makes clear that the Black Cottonwood has sustained the original inhabitants for thousands of years, and his lingering gaze reveals its holy attributes: “your name, your sweet-scented body / your seeping sap nourishing / making medicine to keep / alive hearts barely beating / this word — your name / this tree — your love / wet and shivering has lived” (p. 45).

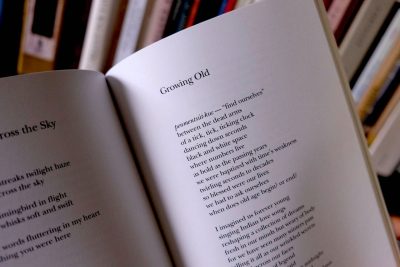

“Clear Memory,” a suite of poems of affection and love, opens with “Eagle-horse was Created in Haida Gwaii,” dedicated to Robert Cross, a poem of connection between Gottfriedson and the nation of Haida Gwaii. It’s followed by “Clear Memory,” a small poem of adoration: “some things are meant / to be forgotten / but I remember all of you” (p. 50). Again, Gottfriedson takes the reader with him on journeys of land to Harrison Hot Springs, Jasper, and Italy, and also on intellectual journeys of appreciation from Leonard Cohen’s poetry and music to that of Joni Mitchell. He revels in the work of other Canadian writers and artists, other Canadian landscapes, other countries, and he revels in romance, affection, and — surprisingly — in growing old.

The bulk of the fourth section, “My Voice,” is devoted to poems on travelling. “Hotel Monteleone, New Orleans,” refers to the famous hotel in the French Quarter of New Orleans, which has been a landmark since 1886. The hotel has a set of Literary Suites that feature décor in the style of literary icons who frequented it or wrote about it — often both — and shaped the literary world of America, namely William Faulkner Suite, Truman Copote Suite, Tennessee Williams Suite, Ernest Hemingway Suite, and Eurora Welty Suite. Hotel Monteleone’s famous Carousel Bar & Lounge is featured in Welty’s short story, “The Purple Hat.”

Gottfriedson directly references Faulkner and his work, drawing attention to his short story, “A Rose for Emily,” which is a fitting comparison to this poetry collection. For Emily is a southern lady in the United States; she is unyielding towards those traditions that once held sway in her world; however, that world is no longer present except in Emily Grierson. She refuses not only to adjust but to let go of the era and traditions that no one else continues to embrace. How she is viewed throughout the story varies depends on who is viewing her. After her death, her actions are revealed. I suggest this is an apt comparison for Clinging to Bone, which struggles against a way of life as well as a set of presumptions, stereotypes, and systems of beliefs that in the 21st century should no longer be applied to the Indigenous peoples of Canada. And just as Emily’s actions reveal her character so, perhaps, the actions of the Canadian Nation reveal who it is.

“Hotel Monteleone, New Orleans,” is followed by “The French Quarter,” a rolling sound-pleasing poem that reveals those fine literary writers who celebrated at the hotel and frequented the city. This section closes with two poems on European cities, “Barcelona” and “Vienna.” In both, the speaker is disturbed by history, ever-present and ever-reminding him of the past and its wrongs. In “Barcelona,” the speaker refers to the Church and its gilded wealth. In “Vienna,” the speaker gestures without mercy to Adolf Hitler, the Nazi regime, Marie Antoinette, the Hapsburgs, and lingers upon a monument “Against War and Fascism.” The House of Habsburg (a.k.a. the House of Austria) ruled in Austria, Germany, Spain, and what was the Holy Roman Empire, rising from merchants to monarchs and popes. The speaker in both poems does not state a specific response to the wealth of the Catholic church, the behaviour of Vienna towards Hitler, Marie Antoinette, the glorification of war, money, the expansion of land, the making of nations, or the close relationship between state and church; however, as Gottfriedson writes: “I fought in no war/ did not betray my people / but I shudder just the same / turn my heart away / write this memory of you” (p. 79). These sentiments are echoed most profoundly in “The Empty Belly of Wind” where, he writes, “the Pope guarantees heaven / but heaven is sold / corporations buy and build fat empires / and monarchs are useless entities” (p. 94). In the final section, “Hunting Ground,” Gottfriedson considers one of the book’s themes more carefully: that of the seasons. His collection closes with: “dissolving winter’s sorrow / among sleeping trees/ scrolling words of peace for us/ winter is gone” (p. 96).

Gottfriedson’s collection is reminiscent of a piece of music with one note reminding us of another, and like a piece of music one sound stands in for many. He uses winter as a season, a time of rest, a metaphor for age, and at the close indicates a passing occurrence. When he turns our attention towards inequity, he does so with a care and patience I find quite astounding. Even when his words indicate disappointment or distaste, Gottfriedson seems tempered: “corporations buy and build fat empires / and monarchs are useless entities / sport killing is the game / currency is the rule / there are no more / heroes or martyrs left” (p. 94).

These are poems of hope and, to sound a bit clichéd, of truth and reconciliation. I would assert that this collection does the work of truth and reconciliation. It offers an unflinching gaze alongside a reconciling nature. It may be that Gottfriedson’s sense of humour assists with the reconciliation, but like all good humour it has the bite of truth in it. As Gottfriedson the horse-breeder and rancher writes in “Earl’s and the Rancher,” “remember who fills your belly” (p. 29).

Clinging to Bone is a seasoned collection that offers a variety of points of view, landscapes, seasons, holy places and spaces, humour, and truth, but its celebration of language is what stands out: the love of words and all their nuances and the generous way Gottfriedson introduces, connects, and celebrates Secwepemectsín. This is a complex and beautifully arranged collection from an equally complex and seasoned writer.

*

Heather Simeney MacLeod is a Métis writer and artist. She has published four collections of poetry, her plays have been performed in Canada and abroad. Two of her plays have won honorable mentions in contests in Canada and the United States. Her creative nonfiction piece, “To Discover the Various Uses of Things,” won first play in the Malahat Creative Nonfiction prize. Her visual art has been exhibited in Victoria and Yellowknife. She is currently a Lecturer at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#797 Secwépemc land and language”