#780 A hot-wired car from Kitimat

Dunk Tank

by Kayla Czaga

Toronto: House of Anansi, 2019

$19.95 / 9781487005962

Reviewed by Marion Quednau

*

Reading Kayla Czaga’s “Dunk Tank” is like taking a ride in a hot-wired car from Kitimat, seeing how far it will take you. She’s in the driver’s seat, taking all the risks in a mood of crazy-young, wanting some traction and the incoming shocks of self-recognition. What Czaga names as trying “to identify/the defect that will qualify you/ as a heroine,” and depicts as a time of “synchronized eye-rolling,” of feeling “inept and sweaty,” everything “urgent enough/ to be the season finale, every day,/ every second in your volcanic skin.”

Reading Kayla Czaga’s “Dunk Tank” is like taking a ride in a hot-wired car from Kitimat, seeing how far it will take you. She’s in the driver’s seat, taking all the risks in a mood of crazy-young, wanting some traction and the incoming shocks of self-recognition. What Czaga names as trying “to identify/the defect that will qualify you/ as a heroine,” and depicts as a time of “synchronized eye-rolling,” of feeling “inept and sweaty,” everything “urgent enough/ to be the season finale, every day,/ every second in your volcanic skin.”

Coming of age is no joy ride. There are no right ways to go out of bounds. We’ve all been there, done that, and have read it all before. Or have we?

Meet poet, Czaga, at age seven, “in a set of panties/so jumbo” …They made your butt look like a Greek column/ of clouds” … “and [you] showed / off your thunderpants to grocery store strangers/…. believing your butt/ would become a skydiver or even prime minister/ of Canada. Who was he who made you — / so many years and underwear sets later, in that/ Honda Civic’s backseat — believe differently?” You’re laughing along until Czaga’s dark comeuppance: it strikes a tone I call “big funny,” the kind linked to pain and sadness.

Czaga grew up in Kitimat, a town with three stop lights/ and skunk stench,” and the proverbial “German restaurant where you ate/schnitzel and buttered rolls, avoiding/ [your mother’s] discussion of your future.” “Try to look at it differently,” says Czaga. “Tell me the salmon sexing/ to death in the Skeena are beautiful/ in their pursuit of home,…that the man three beers deep/ running his dog alongside his pickup/…is really Walt Whitman.”

She’s inventive, resilient: you can tell she’ll survive, but not necessarily escape. “Your memory/ freezes and thaws again and again./ You return every year/ on a twelve-passenger plane/ that descends by spiralling around/ an onion-shaped lake, woods/ an Emily Carr retrospective,/ a walloping green nausea./ Your ex says, See you next/ Christmas!…You blow/ smoke behind the North Star Bar,/ while inside your dad retells/ the same three stories — your life/ less of the arc he expected and more/ like a cedar growing in rings,/ circling, circling.”

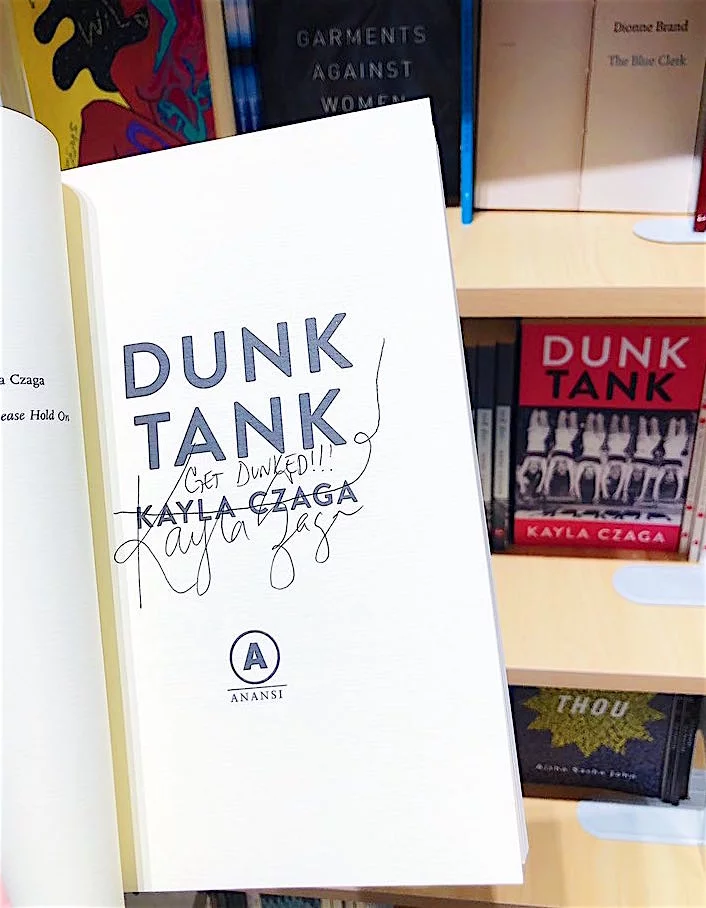

This hovering image, encapsulated in the book’s title, suggests youth might be an exercise of waiting to be made foolish, with witnesses, over and over. The cover depicts a gaggle of mid-century girls hanging upside down from monkey bars; not exactly a dunk tank, but there is a puddle beneath them, showing their headless-seeming shadows. When you tilt the text upside down, examine the faces of the upended girls, although they are smiling, they’re posing, and on several faces you can see a barely disguised look of anguish, of “let’s get this over with.” Who knows how long they’ve been dangling in an aspect of long legs, small waists, and shorty shorts, the near-sexual promise of lithe bodies, of coy innocence waiting to fall.

If some poets make a point and then expand on it, Czaga casts it wide and then reins it in. In “Money,” she laments that “Most of what we do isn’t living — / it’s laundry, it’s operating/ a can opener, it’s passing/ beautiful people on the street/ then never seeing them again./ Or meeting them and discovering/ they’re awful on the inside.” She gives us glimpses, not the whole story, pivotal changes of direction. She admits to reading “interesting articles about shit/ in Bangladesh, Wisconsin,/ or deep in the tissue papers/ of the gorilla heart,” then lands her punch. “Last night between hellos/ with literary near-strangers/…the feeling of really/ living crushed through me/ like a ghost elephant lowering/ its ghost feet and impeccable/ ghost memory onto my skeleton,/ and I wondered if everyone/ or even just Michelle/ could tell I was crying.”

Czaga never lulls you into a false sense of safety, because, in truth — even in the telling of it — there is no safety. In “Drunk River,” which doubles in meaning throughout the poem as “drunk driver,” she’s “starring in some boy’s sucky/ idea of a first date…while a stranger weeps/ through the radio” of the lost girls along Highway 16: “You think of the man and his pig farm./…pink/ snouts, squealing, eating up little bits,/…think/ of …the pink/ snouts, the girls, and you want to know/ if you are pretty. Despite all the trouble/ it causes, you want to know if you are pretty/ here, tonight, in this truck beside this drunk river.”

Czaga creates order from disparate-seeming imagery with an intuitive knack for repetition. In the poem, “Aluminum,” the mention of salmon is repeated to variously suggest sex and death, Walt Whitman’s “silver beard dotted with pipe ash/ and nostalgia,” and also refers to her mother’s aging, her hair “as so many spawning salmon.” In “Naanwich was the Last Thing,” the words “nothing” and “love” ring like clanging church bells calling us to aloneness and shame. Czaga writes, “I still feel the warm thumbs of priests/ on my head reminding me I am nothing./ Wait, you said, that’s not all of it./ You are nothing “if you are/not loved.” On shitty white bleachers/ beside a baseball diamond you said/ you could no longer love me./ Teenagers passed us kicking wet stones./ You couldn’t love me.”

Czaga creates order from disparate-seeming imagery with an intuitive knack for repetition. In the poem, “Aluminum,” the mention of salmon is repeated to variously suggest sex and death, Walt Whitman’s “silver beard dotted with pipe ash/ and nostalgia,” and also refers to her mother’s aging, her hair “as so many spawning salmon.” In “Naanwich was the Last Thing,” the words “nothing” and “love” ring like clanging church bells calling us to aloneness and shame. Czaga writes, “I still feel the warm thumbs of priests/ on my head reminding me I am nothing./ Wait, you said, that’s not all of it./ You are nothing “if you are/not loved.” On shitty white bleachers/ beside a baseball diamond you said/ you could no longer love me./ Teenagers passed us kicking wet stones./ You couldn’t love me.”

This “echo effect” lends a cadence of “escape and return” throughout the book, the words “salmon,” “panties,” and “ghost” appearing in different gestalts to keep our attention on what matters. I did somewhat resist Czaga’s constant use of a name in the “Kyla” poems. In fiction we’re invited to look over someone’s shoulder, to imagine their privacies. But in verse directed at a real someone, I felt excluded and tried reading all the poems without so many, or even a single mention of “Kyla.” It freed up the poems, allowed greater intimacy and paradoxically made room for the reader. We don’t need to know who it is, but rather how it feels. A more nuanced “you” as point of departure would have avoided the cul-de-sac of having to footnote a poem, insisting the woman described here was a “different Kyla,” which felt heavy-handed for such a deft poet.

This “echo effect” lends a cadence of “escape and return” throughout the book, the words “salmon,” “panties,” and “ghost” appearing in different gestalts to keep our attention on what matters. I did somewhat resist Czaga’s constant use of a name in the “Kyla” poems. In fiction we’re invited to look over someone’s shoulder, to imagine their privacies. But in verse directed at a real someone, I felt excluded and tried reading all the poems without so many, or even a single mention of “Kyla.” It freed up the poems, allowed greater intimacy and paradoxically made room for the reader. We don’t need to know who it is, but rather how it feels. A more nuanced “you” as point of departure would have avoided the cul-de-sac of having to footnote a poem, insisting the woman described here was a “different Kyla,” which felt heavy-handed for such a deft poet.

The self-described “smart girl” of Dunk Tank, “you’re sitting/ on nothing and you think maybe/ you won’t fall after all” gives us lots of fun and games with language. Czaga says, “I texted you, “Finnish/Schooling,” and I’m sorry/ if you took it as a command./…In Finland kids are/ so happy. They don’t/ have homework. They/ read Ishiguro novels/ while whittling cedar/ computers …” In “Narrative Theory,” she uses the word “hole” in various guises of lack or unfinished business set against Aristotle’s theory of a “whole” in storytelling. “At seventeen you fled with a suitcase,/ thinking, Thank you, Aristotle,/ this is the end of the hole.” Her poem, “Fun and Games,” about living above a nightclub, where girls “mistakenly stumble up our stairs./ What fun their ankles seem to have,/ rolling out from under them” made me think of the Billy Collins poem, “Nightclub,” where the poet accepts the offer of playing a sax onstage, feeling how foolishness and beauty collide: it’s one of Czaga’s poignant themes beneath her crackling wit.

One of the joys of reading a new book is where it leads you. I was variously led to Walt Whitman, Robert Hass (her mention of his poem with blueberries), to rereading Alice Munro’s story, “Wild Swans,” and was led back to every single Canadian small town I’d ever driven through as a young publisher’s rep on the prairies, how I knew all the good diners with, yes, that knock-off German schnitzel. Czaga’s sensations of feeling trapped and hectic, wanting to up the ante, reminded me of teaching creative writing for a short stint in BC’s northernmost towns, where the kids thought everything important was happening elsewhere, could spell “Lamborghini” but not necessarily “salmon fry,” a pregnant fourteen-year-old confiding that she “did it, because she wanted to be loved.” I think she meant unconditionally — by the child, not the father — but I wasn’t sure.

Good poetry resonates on different levels, leaves you thinking about your own life for some time beyond. And in this regard Czaga’s poems leave you laugh-crying and changed, returning home. I found a tone of fierce tenderness in the book’s last poems, as in “The Newspapers,” the poet readying a café before it opens: [I] “shift from foot to foot testing balance/ and consciousness….love these/ brief moments with the blueberry muffins.” In “Mosquitoes,” she recalls, “My father taught me/ math and racism and he/ loved me very much./ He taught me money/ and aliens inventing / the pyramids. He/ showed me how to act/ like my grandmother/ who acted like a man/ so men wouldn’t fuck her/ over so often.” The book’s final lines are plain-spoken, so beautiful: “Mosquitoes lifted/ my grandmother/ like she was an apron/ filled with blackberries/ and carried her/ into the sky. She hoped/ the feeling she called/ God would call her/ name and she would live/ with him, faithful husband/ who fixed the crooked/ shed door, fed the chickens/ and footed his half/ of the rent forever/ and ever amen.”

I was struck by Czaga’s “haunted” feeling of doubt in this final poem: “I thought/ if I left Wohler Street,/ if I made poems,/ if I dated the bass/ player and married/ the Lord, kept friends/ and carried beer/ for a living, I’d feel/ differently, but I don’t./ I don’t feel any different.” Now this, I thought, is the hardest part about coming of age. And about writing. Here’s a poet who’s hard on herself, and has grown, whether she knows it or not.

Her honesty reminded me of American poet Mark Doty’s words in addressing a crowd of young poets emerging, as it were, from their own “dunk tanks” of hovering, hoping to make memorable splashes. “Courage is not something that you just get once and then you keep it. It’s something you lose every single day, and you find some more if you’re lucky.”

*

Marion Quednau has won numerous awards, her work appearing most recently in Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis) and Sweet Water, ed. Yvonne Blomer (Caitlin Press, 2020). Her poetry collection, Paradise, Later Years came out in 2018 with Caitlin Press; see The Ormsby Review no. 648, reviewed by Renée Sarojini Saklikar (Nov. 4, 2019). She lives on BC’s Sunshine Coast in a ferry-riddled cadence of escape and return.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors.

The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster