770 Fractured fidelities

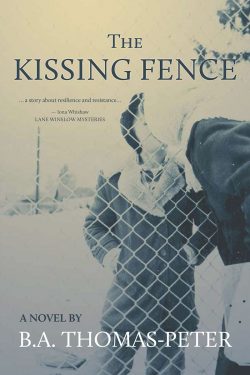

The Kissing Fence

by B.A. Thomas-Peter

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2020

$24.95 / 9781773860237

Reviewed by William New

*

This novel tells the connected stories of two boys. One grows up in the 1950s, but his entire life is damaged when he is forced away from his Doukhobor home and placed in a Kootenay residential school; the other (we find out in due course) is his middle-aged son, whose adult life in Vancouver half a century on is also in upheaval — in his case because of an affair, a tumour, a corrupt business deal, and his awkward parenting skills (these in turn the result of his own disrupted upbringing). In other words, by means of two intertwined narratives, the novel confronts several historical issues in B.C. and addresses their contemporary consequences and parallels: the Sons of Freedom (or “Freedomite”) Doukhobor resistance to “English” norms in the 1950s, and (related to this movement) various social biases and police actions, sexual predation, self-loathing, rootlessness, susceptibility to power, faith, family tensions, the occasional sensitive but usually ineffectual authority figure, and the checkered possibility of survival. Mental health is key here, and context is all.

This novel tells the connected stories of two boys. One grows up in the 1950s, but his entire life is damaged when he is forced away from his Doukhobor home and placed in a Kootenay residential school; the other (we find out in due course) is his middle-aged son, whose adult life in Vancouver half a century on is also in upheaval — in his case because of an affair, a tumour, a corrupt business deal, and his awkward parenting skills (these in turn the result of his own disrupted upbringing). In other words, by means of two intertwined narratives, the novel confronts several historical issues in B.C. and addresses their contemporary consequences and parallels: the Sons of Freedom (or “Freedomite”) Doukhobor resistance to “English” norms in the 1950s, and (related to this movement) various social biases and police actions, sexual predation, self-loathing, rootlessness, susceptibility to power, faith, family tensions, the occasional sensitive but usually ineffectual authority figure, and the checkered possibility of survival. Mental health is key here, and context is all.

Think about 1953, the year when this novel begins. Take it as emblematic of its decade. The 1950s was not as bland as current conventions imagine, not as innocent as television sitcoms make it out to be, and definitely not without incident or import. World leaders in 1953 included Eisenhower, Khrushchev, Churchill, Mao, Nehru, and (in Canada) Louis St. Laurent. The USSR announced H-bomb tests, the CIA aided a coup in Iran, the McCarthy trials were still underway, Stalin died, Elizabeth was crowned Queen. Ian Fleming published the first Bond novel and Playboy first appeared on magazine stands. The Stratford Festival started in Ontario, the (first) Trans-mountain oil pipeline was completed, the first colour TV went on sale in the USA, the Salk vaccine was being tested, Hilary ascended Everest (Tenzing Norgay was seldom mentioned), and Crick and Watson announced the double helix DNA structure. Not uncharacteristically, the decade in retrospect looks like a power struggle between convention and possibility, control and flash: neither one a uniform arbiter of value.

In B.C., the Doukhobor settlements of the West Kootenays became “news” in the 1950s when conflicts arose both within the community and between some Freedomite members of the faith and the public at large. It’s important to this novel to keep in mind the history that lies behind this conflict, for the Doukhobor faith (Doukhobor = “spirit wrestler”) was not born in the Kootenays in the 1950s, but has 18th century roots in Russia, where for some years it was tolerated as a religious alternative before its espousal of pacifist and spiritual values and its rejection of priests and rituals ran up against Russian orthodoxies.

In the early 19th century many of the faithful were exiled to Finland and Turkey; many others were absorbed into existing (largely Baptist) congregations; and yet another option opened when, towards the end of the 19th century, the Canadian government offered land in Saskatchewan to some 7500 adherents of the faith. They later moved to BC, settling in Brilliant, Krestova, and Grand Forks — their move brought about in part because changes in legislation were asking for individual registration of land ownership, and the Doukhobor community, collectivist by belief, was resisting this new requirement.

By the early 20th century, other divisions were surfacing. In Canada (as in Russia), more members began to accept integration into local social practices; while some — the Freedomites — refused to do so. They continued to speak Russian (resisting English), they burned down community houses (rejecting “ownership”), they would not send their children to public schools, and they would not serve in the military. Some men and women (refusing to wear any “uniform”) began to parade in the nude, which became “news” when public authorities and newspaper journalists, focussing on the protests, started calling for action — meaning police action — in the name of decency, morality, and the law; the Social Credit government of the day also legislated the summary removal of Doukhobor children from their parents so that they could be placed in a residential school in New Denver, in the Slocan Valley. (Parallels between this decision and that which established residential schools for First Nations children can readily be inferred.)

Much has been written about the Doukhobor faith and the events of the 1950s, ranging from Simma Holt’s Terror in the Name of God (1964), critical of the Freedomite actions, to The Doukhobors (1977) by George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumovic, which is sympathetic to the pacifist causes of the faith and the intellectual anarchism of the faithful. Andrew Donskov and others edited The Doukhobor Century in 2000.

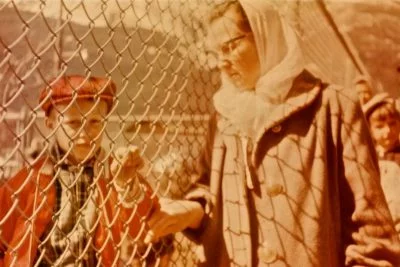

The Kissing Fence is written against this context, fastening less on competing articles of belief than on the serious consequences of a forced removal. The novel paints terrible conditions: the children are pursued and captured, ill fed and badly treated, separated from loving parents (their only contact is at the wire fence at the school’s edge, where kissing from one side to the other is at least a dream of survival). Good clothes that the parents design and take to the school are not delivered to the children but are stolen and used by the school administrators instead; the same goes with specially cooked foods. The children are punished if any one speaks in Russian (which therefore becomes a kind of secret code). The communal conditions they are constrained to live by, in short, have little to do with the communal faith of the people at home. Some of the children find support with each other, but the overall picture is grim.

While at least one policeman is shown to be sensitive to the children’s plight, he is portrayed as powerless to act effectively, challenged at once by the distrust of the children and by the insults of his fellow officers for showing “weakness” and being faithless to the force. But he is an exception. More characteristic of the portraits in this book are those that detail threat, cruelty, dismissiveness, exploitation, and more. The boy who is at the heart of the 1953 section of the novel is sexually molested by a school official. This act has consequences: the boy’s self-loathing, something he cannot escape even later, leads to his isolation and (however indirectly) to the inadequacies that bedevil the next generation. His son, the city businessman whose story is told in the 2017 sections of the novel, has long been separated from his parents and his faith; his infidelity disrupts his marriage; and his inability to trust any standard of shared social mores threatens his life and his capacity to love — with implications for yet another generation in the offing.

The author, B.A. Thomas-Peter, brings to this portrayal of generational divide his long experience as a psychologist and forensic psychiatrist, largely in Britain but also more recently in BC. The Kissing Fence recalls one (of all too many) distressing and damaging episodes in B.C. history, animating events through a fictionalized case study, profiling behaviours and drawing concrete attention to differences between two notions of security. There is little lightness in this novel — whether of observation or of style — but that is not the author’s intent. Earnest in both manner and message, Thomas-Peter is being serious about serious issues, some of them involving faith and justice, cruelty and the law, but mostly (focussing as he does on the fractured lives of his two main characters) about what happens to the mind.

*

William New is the author of Reading Mansfield & Metaphors of Form (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. He is also the author of a dozen collections of poetry, including The Rope-Maker’s Tale (Oolichan Books, 2009) and Neighbours (Oolichan, 2017).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors.

The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “770 Fractured fidelities”

Well done Bill! Good story & great review.