#767 The Vancouver patchwork

Jennifer Chutter reviews 2 books:

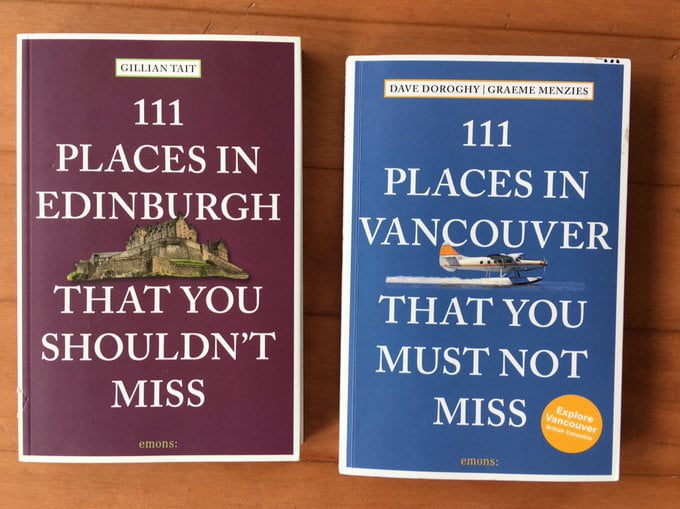

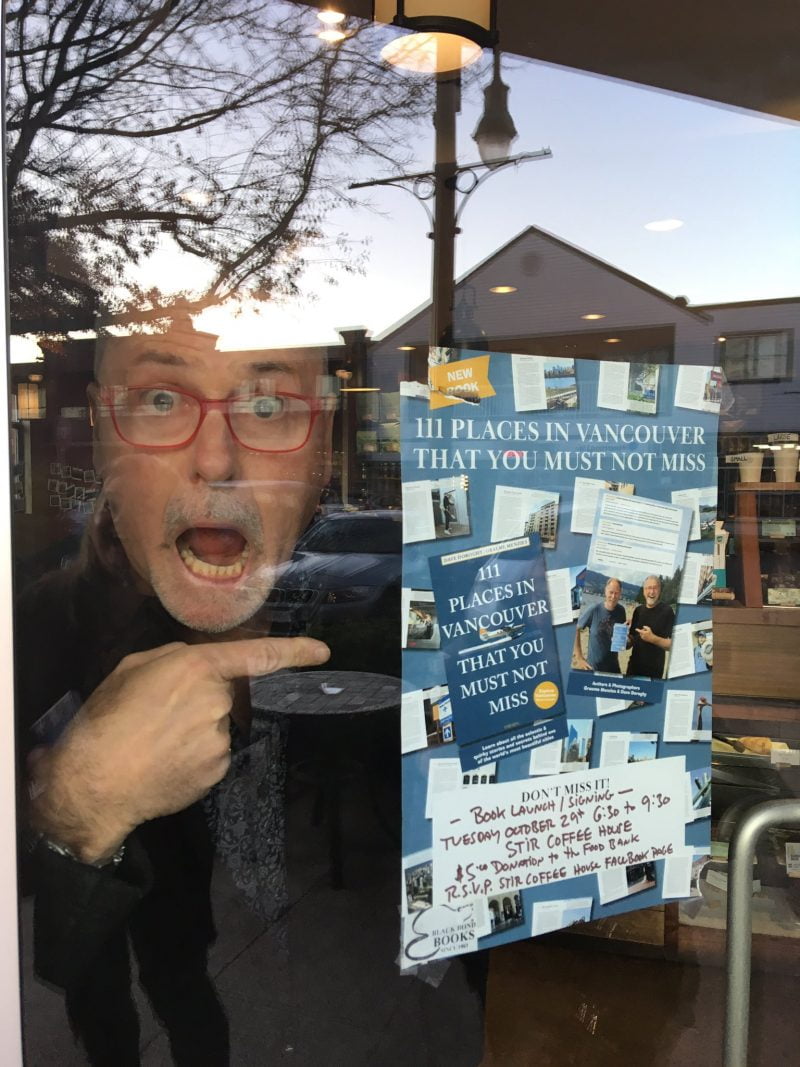

111 Places in Vancouver That You Must Not Miss

by Dave Doroghy and Graeme Menzies

Cologne and New York: Emons Verlag, 2019

$26.90 / 9783740804947

*

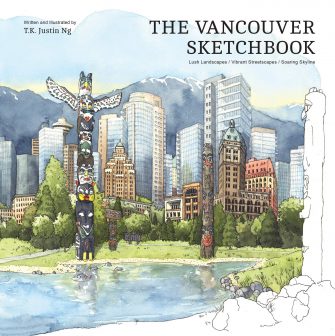

The Vancouver Sketchbook: Lush Landscapes, Vibrant Streetscapes, Soaring Skyline

by T.K. Justin Ng

Vancouver: Whitecap, 2019

$29.95 / 9781770503250

*

Pictorial depictions of Vancouver tend to feature multiple mountain vistas, expansive ocean views, and lush and verdant landscapes. The city is frequently featured as nestled into the dramatic physical geography rather than an impressive entity in itself. 111 Places in Vancouver That You Must Not Miss, by Dave Doroghy and Graeme Menzies, and The Vancouver Sketchbook by T.K. Justin Ng, offer new pictorial insights into the city that challenge the reader to see the beauty in Vancouver’s built urban form. Doroghy and Menzies present the city as it is now, in bright and vibrant colour photographs, and then loosely trace backwards to ask why the city developed the way it did. Ng’s watercolours create an intimate and personal connection to the city. Through his eyes the city is rendered soft and inviting to the urban wanderer, and the text unfolds with only a loose connection to its history of urban development. Read together, the two books overlap and diverge in interesting ways to establish Vancouver as a dynamic and diverse West Coast city where the natural topography recedes into the background – a withdrawal that, in turn, allows the different urban forms to dominate the foreground.

111 Places In Vancouver offers a snapshot approach to exploring the city. Arranged alphabetically, the 111 sites have no clearly definable order or focus; the reader can dip in and out to uncover different aspects of the city’s culture including museums, historical sites, places to eat and drink, and unusual places to visit. Conveniently, 111 Places is published in a travel guide size that encourages one to take it along while urban adventuring. The book is beautifully laid out with text on the left-hand side accompanied by a photograph and useful information on the right-hand pages. The right-hand insert reads like a travel guide; the small insert boxes include tips such as how to get to the destination, hours of operation, and nearby places to visit. As a resident of Vancouver, the book surprised me with features I did not know about, and descriptions and directions to new places makes them easy to explore on my own.

111 Places In Vancouver offers a snapshot approach to exploring the city. Arranged alphabetically, the 111 sites have no clearly definable order or focus; the reader can dip in and out to uncover different aspects of the city’s culture including museums, historical sites, places to eat and drink, and unusual places to visit. Conveniently, 111 Places is published in a travel guide size that encourages one to take it along while urban adventuring. The book is beautifully laid out with text on the left-hand side accompanied by a photograph and useful information on the right-hand pages. The right-hand insert reads like a travel guide; the small insert boxes include tips such as how to get to the destination, hours of operation, and nearby places to visit. As a resident of Vancouver, the book surprised me with features I did not know about, and descriptions and directions to new places makes them easy to explore on my own.

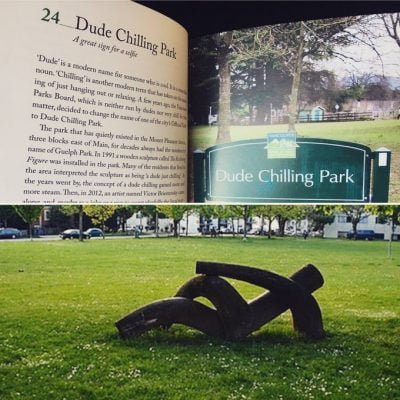

What I enjoyed reading about most were quirky details about the city. Gaining insight into how Dude Chilling Park (no. 24) got its name, how 1 Gaoler’s Mews (no. 34) became a trendy shopping area in Gastown, and why the BowMac sign (no. 12) persists under the Toys R Us sign on West Broadway added to my knowledge of the city — things I’ve wondered about as I drive around the city, but forget to look up when I get home.

What I enjoyed reading about most were quirky details about the city. Gaining insight into how Dude Chilling Park (no. 24) got its name, how 1 Gaoler’s Mews (no. 34) became a trendy shopping area in Gastown, and why the BowMac sign (no. 12) persists under the Toys R Us sign on West Broadway added to my knowledge of the city — things I’ve wondered about as I drive around the city, but forget to look up when I get home.

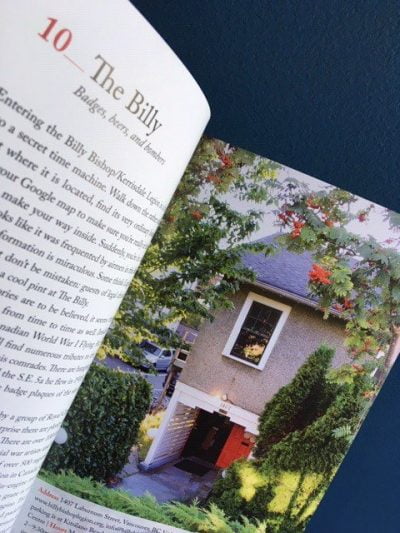

I enjoyed reading about hidden historical gems in the city like The Flying Angel Seafarer’s Club (no. 31), which was the original office of Hastings Mill, constructed in 1906, and The Billy (no. 10), which is the Billy Bishop-Kerrisdale Legion tucked into the neighbourhood of Kits. The book includes other lesser known points of interest like the Coupe de Villa (no. 20), featuring “a classic 1960 Coupe de Ville Cadillac” cut in half and buried in the front yard of a residential property, and the Twin Urinals (no. 104) in Heritage Hall on Main Street. Both of the sites will make you ask “Why?!” And knowing the answer adds to one’s personal store of Vancouver trivia. I appreciated the equal attention given to Vancouver heritage and Vancouver oddities. Doroghy and Menzies have collected a diverse range of points of interest in the city to appeal to a broad cross-section of Vancouver residents.

However, some of the entries could have been expanded with stronger local context. For example, Brassneck Brewery happens to be located at the site of the city’s original brewery district. Many new craft breweries have sprung up in the surrounding Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, making it now a great location to walk through and sample local beers. 111 Places also illustrates how Vancouver’s light industrial areas are slowly being gentrified with expanding apartment building construction from surrounding areas. Surprisingly, the Vancouver Art Gallery is not included, which seems particularly short-sighted since it is a frequent site of protest rallies, and it is the former city hall, which gives the building many layers of cultural significance. The pedestrian-only area of Robson Street between Howe and Hornby also deserves mention for its food truck culture and the local artists selling their wares, and Robson Square’s ice rink is a hidden urban gem tucked below street grade.

However, some of the entries could have been expanded with stronger local context. For example, Brassneck Brewery happens to be located at the site of the city’s original brewery district. Many new craft breweries have sprung up in the surrounding Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, making it now a great location to walk through and sample local beers. 111 Places also illustrates how Vancouver’s light industrial areas are slowly being gentrified with expanding apartment building construction from surrounding areas. Surprisingly, the Vancouver Art Gallery is not included, which seems particularly short-sighted since it is a frequent site of protest rallies, and it is the former city hall, which gives the building many layers of cultural significance. The pedestrian-only area of Robson Street between Howe and Hornby also deserves mention for its food truck culture and the local artists selling their wares, and Robson Square’s ice rink is a hidden urban gem tucked below street grade.

While I recognize the need to conform to the publishing convention of only discussing 111 sites, as with numerous other books in Emons Verlag’s series about cities around the world, I felt the Floating Gas Station (no. 30) did not need its own entry, since it is featured in the background of Harbour Air and the entry might have been condensed into the right-side insert. The entry on the Trump Tower (no. 102), with its humorous image of someone wearing a Donald Trump mask in front, could have been added to UBC Museum of Anthropology entry (no. 70) — a startling suggestion until one realizes that both buildings were designed by the well-known Canadian architect, Arthur Erikson. Both entries could have been cut entirely to make room for sites that encourage the convergence of people from diverse and wide-ranging backgrounds.

*

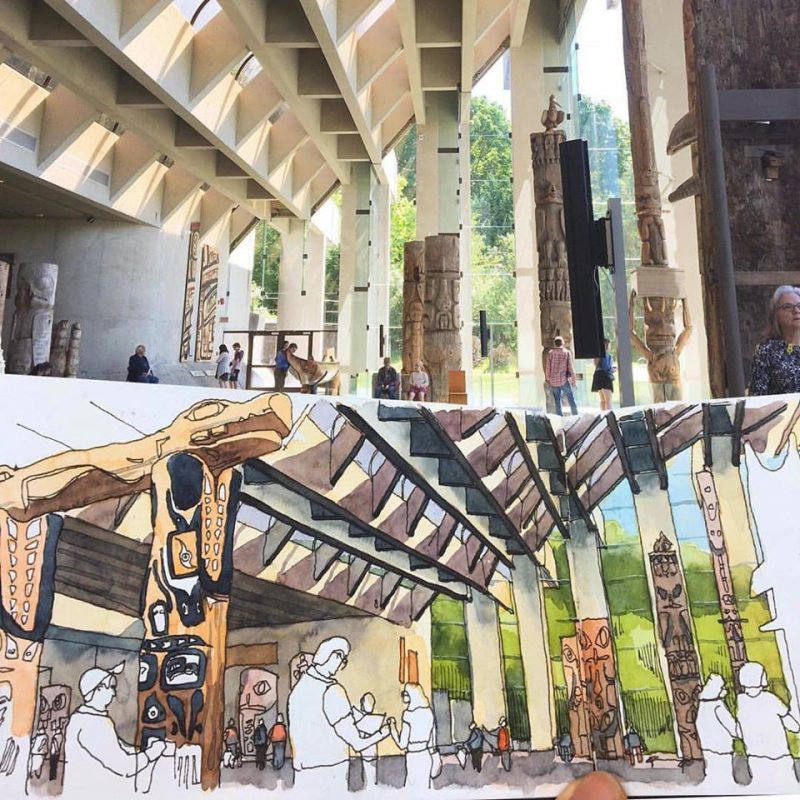

Justin Ng’s The Vancouver Sketchbook offers a different view of the city through its beautifully illustrated sketches and watercolours, and Ng takes the reader on his personal journey through the city via his active artwork. The book is arranged thematically into seven sections that loosely capture the city’s urban development and provide a focus to the images. Ng suggests that “not only is each drawing an opportunity to capture memories of a place, each is also a lesson on architecture and urbanism” (p. 5). It is through sitting and sketching Vancouver that the beauty of its built environment and natural setting becomes more apparent to Ng – and then to the reader. The accompanying text is part autobiographical, part historical, and part descriptive commentary on the sites illustrated. Ng includes quirky locations to capture different aspects of the city’s urban form. Views of the city from above from the observation deck of the Harbour Centre Lookout (pp. 80-81) provide a bird’s eye view of the streets below. Theatre Row (pp. 76-78) provides a different sense of the history of the city as an entertainment district. This contrasts nicely with the Twin Viaducts (pp. 72-73), which have shaped the city’s built form differently from other North American cities. The inclusion of many places in Chinatown helps to illustrate the non-European heritage of the city, which is frequently omitted, and the inclusion of apartment towers is a welcome addition since because many texts on cities do not include images of residential areas, favouring instead commercial and recreational sites.

While the illustrations are worth gazing at and coming back to, I found The Vancouver Sketchbook somewhat limited by its origins as catchall for the sights and sites Ng found interesting during his summer stay at his grandparents’ apartment in Vancouver. In turn, Ng’s historical/ autobiographical text provides a rather fluid sense and sometimes limited sense of how Vancouver is defined as a geographical location. An image of the Rocky Mountains juxtaposed with sketches of Grouse Mountain and Lynn Canyon seems out of place because they are geographically so very far apart. Unfortunately, the inclusion of images outside of Vancouver and the Lower Mainland repeats itself and becomes distracting. It is not always clear why some images are clustered with ones from Vancouver. For example, an image of Britannia Mines is sandwiched between two images of Stanley Park (pp. 22-23), and the Legislature in Victoria is paired with Vancouver’s City Hall. Some explanation to Ng’s readers of why these places interested him would help to tighten the overall focus of the book.

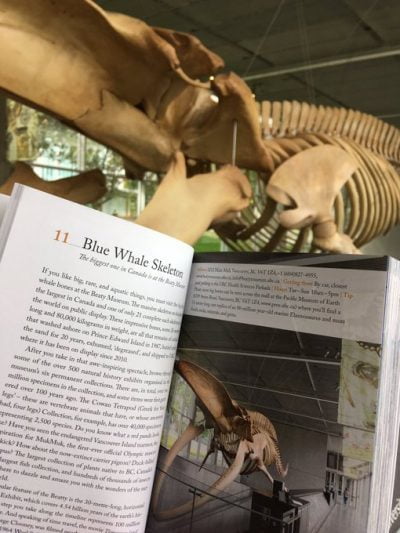

Read together, 111 Places and The Vancouver Sketchbook overlap and in the process reveal different aspects of the same locations. For example, Ng’s illustrations focus on the beauty of Stanley Park, in keeping with the typical park narrative. Doroghy and Menzies disrupt this narrative by including the Nine O’Clock Gun (no. 75) and the hidden symbols carved into the rocks along the seawall near Third Beach (no. 48). These combined views of Stanley Park reveal its complexity — its beauty, its military history, and a bit of whimsy. Other points of overlap provide interesting glimpses of the city’s history. The Beaty Museum at UBC explores the natural world and the Museum of Anthropology provides an understanding of Indigenous cultures in BC. The arrival of Europeans is symbolized with the preservation of Engine 374 and Waterfront Station. The industrial expansion of the city is referenced with the transformation of Granville Island. Each book contributes to an understanding of how the city’s urban form developed for these human occupations.

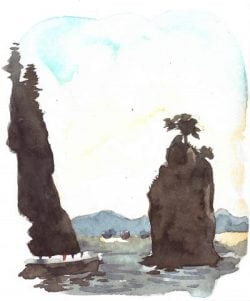

My main frustration with both books is the treatment of First Nations’ histories. While both acknowledge that the Coast Salish Nations lived in Vancouver prior to European settlement, neither portrays the living aspects of Indigenous cultures today. Though Ng does include the Parks Board commissioner Catherine Evans proposing the changing of the name of Siwash Rock, meaning sauvage, to Skalsh, meaning Standing Man (p. 14), this point could be pushed further to explain why changing the name is an important part of reconciliation. Ng also mentions that many of the totem poles in Stanley Park are not connected to the Indigenous Nations whose territory included the park; but again, he might have explained how this collection of poles from many distant coastal First Nations came to be there. Equally, the poles on the front cover of The Vancouver Sketchbook, oddly set against a foreground of the city, have been taken out of context to give the impression that they are merely decoration rather than an important part of the continuing First Nations presence in Greater Vancouver.

Similarly, in 111 Places, a photograph of the enormous billboard at the South end of the Burrard bridge could have been used to draw attention to the small section of land owned by the Musqueam Nation and their plans for redevelopment there, and include further suggestions to visit the welcome totem pole underneath the Burrard bridge. While I recognize that discussing reconciliation was not the focus of these books, I do think it is important to promote reconciliation and not simply perpetuate stereotypes. In both books, more could have been done to embrace reconciliation without disrupting their overall structure.

Despite these reservations, 111 Places and The Vancouver Sketchbook will be welcome additions to a Vancouver bibliophile’s collection or a lovely gift to a homesick expat.

*

Settler Jennifer Chutter is an award-winning PhD student at Simon Fraser University. Her dissertation research is on the formation of the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA) and how they advocated for their sense of home and place within the neighbourhood. Their agency and activism bring to light the legacy of colonial structures within the city and emphasize the importance of preserving and designing neighbourhoods to foster a sense of belonging and inclusion. Her previous research was on the Vancouver Special and its importance as a localized form of architecture. Previously she reviewed Dear Current Occupant: A Memoir, by Chelene Knight, for The Ormsby Review (June 13, 2018). Jennifer feels most at home in Vancouver when she smells the salty air while running along the Stanley Park seawall.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#767 The Vancouver patchwork”