#752 Updating Bill Barlee

Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns in British Columbia

by N.L. (Bill) Barlee

Surrey: Hancock House, 2018. First published serially by Canada West Publications, 1970-72; first published in a single volume by Hancock, 1980, reprinted 1984, 1988, etc.

$29.95 / 9780888399885

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

The mainland of British Columbia was created hurriedly as a colony in 1858 to assert British law over a rush of Americans looking to become placer gold miners. As the Fraser Gold Rush played itself out, followed by a string of other rushes in the Similkameen, the Boundary, the Okanagan, the Cariboo, and the Stikine, placer mining and British Columbia grew up together.

The mainland of British Columbia was created hurriedly as a colony in 1858 to assert British law over a rush of Americans looking to become placer gold miners. As the Fraser Gold Rush played itself out, followed by a string of other rushes in the Similkameen, the Boundary, the Okanagan, the Cariboo, and the Stikine, placer mining and British Columbia grew up together.

Eventually, placer gold mining turned to hard rock mining, sporadically at Fairview and spectacularly at Hedley. Coal was also mined, as were copper, silver, lead, zinc, and molybdenum. Currently, British Columbia is a world leader in mining, with an income of $5.6 billion, almost double what it was twenty years ago.

Modern mining is a heavily-industrialized, open pit business, the stuff of huge corporations, stock markets, and holding dams, an industry that pursues its work with teams of lawyers amid questions about water, salmon, and Indigenous sovereignty. It’s not very romantic.

But placer mining, ah! Now that still holds its allure, even though the business never was as romantic as it was advertised to be. A lot of gravel has to be moved with a lot of water to find a little gold. Most miners lost their health and their shirts.

Still, to call yourself a placer miner, all you really need, even today, is a gold pan, a shovel, and a cheap placer licence from the BC government. That’s romantic. If you’re smart, lucky, and strong, and set out up the right creek, who knows. You might find a few million dollars lying around — or at least a flash in the pan to make your heart beat faster.

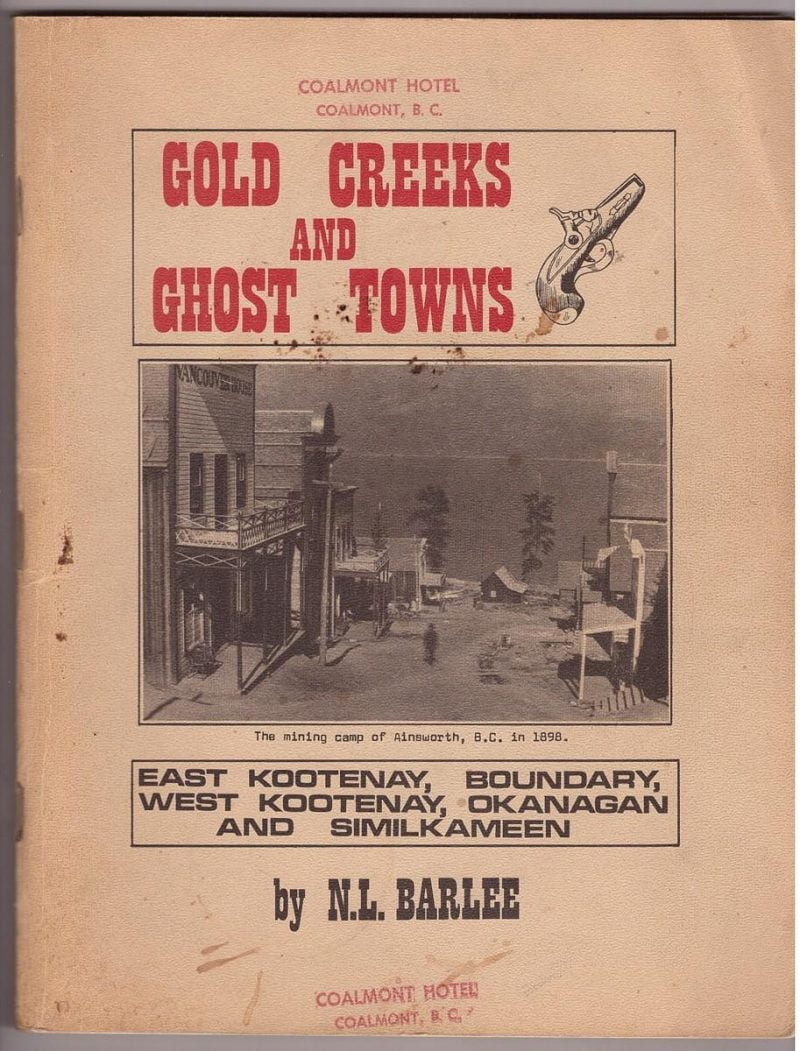

That’s where Barlee’s Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns in British Columbia has come in as a handy guide and folksy story-telling companion for three generations now. It’s a level of success that few British Columbian books can match. Perhaps only Roderick Haig-Brown’s reflections on salmon fishing, written mainly in the 1950s, and Muriel Blanchet’s The Curve of Time (1961) now exceed it in longevity. Barlee’s immensely popular book — based on his equally popular Canada West Magazine — has now been reprinted, so that it can continue to lay out the history of gold camps and placer mines in BC for a whole new audience and generation.

For that, it’s welcome. Barlee’s love of his country is contagious, and his is a companionable and knowledgeable guide. A publishing decision to retain the old self-published feel of the original book (hand-drawn maps and illustrations, and the whole thing printed on a typewriter) gives it a level of tried-and-true authenticity. On the other hand, the content of the book is showing signs of age. It’s good to see it here as an old friend, and its honouring of gold rush towns otherwise forgotten is invaluable, but it would have benefitted from a proper remake.

In short, Gold Trails and Ghost Towns is a classic. It portrays a historically-significant part of the province’s past in unduplicated detail. Its love of the land and its history is contagious, and it contains a treasure trove of material you will find nowhere else. It is extensively illustrated. It has been in print for so long now that it has been a historical artifact of its own. If you’re looking for treasure in BC, you can find a lot of it in this book.

The estimated 40,000 Americans who came in 1858 weren’t the first to gather gold and convert it into wealth here, but their cultural legacy remains deeply woven into Barlee’s book. He is a proud Canadian and a proud British Columbian, yet this book is essentially American in style and outlook. It presents a history that almost exclusively honours settler culture, romanticizes it, and avoids its problematic legacies. It gives precise and detailed knowledge of sites of settler activity. It is uninterested in Indigenous mining, in the land itself, or how the land might lead one to minerals, although that is the business of contemporary prospectors. In exchange, it is folksy and companionable.

These are all attributes of Western American popular history from the 1830s to the 1970s. This style lives on in many popular histories presented on the Internet today. Perhaps Barlee scoured so many old newspaper accounts to write this book that he was infected by their romance. We might never know.

One of the enduring strengths of Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns in British Columbia is that it’s not just about Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns. It is also about the First Nations of BC, or at least those of the Similkameen, the Okanagan, and the Boundary. This legacy is problematic.

On the one hand, Barlee has included hand-drawn maps that mark Syilx place names and sites of historical significance. These are welcome. He was very inclusive for his time. Contemporary maps don’t list these sites. Only Barlee has kept them in the popular imagination. Mind you, it is just plain sad that the good work he initiated was not taken up again and extended. It’s been over half a century, after all.

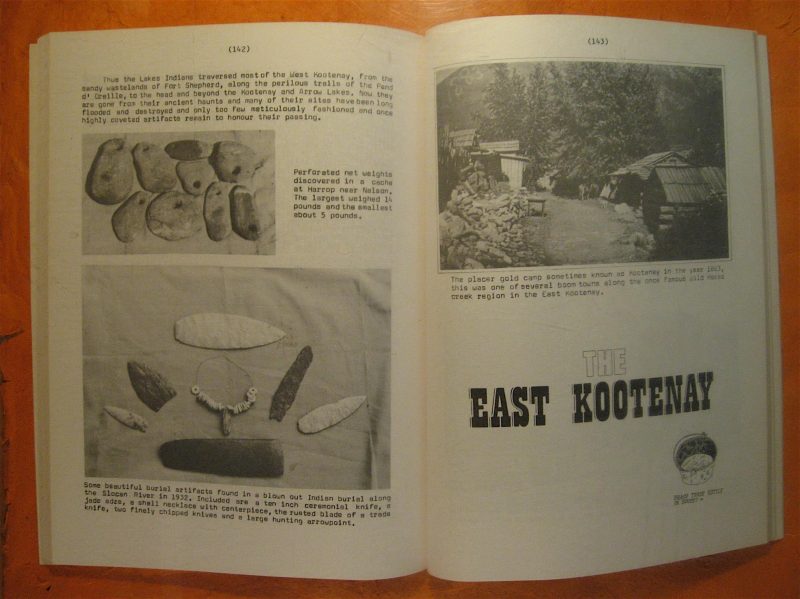

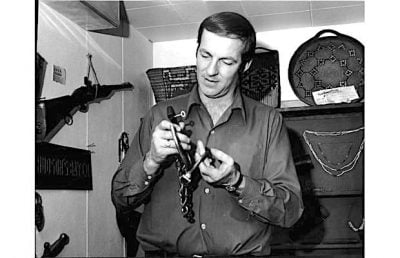

On the other hand, Barlee appears to include these sites as markers for another kind of treasure-hunting: the illegal collecting of Indigenous artifacts. He illustrates the artifacts he has found, as well as others from various private and public collections throughout the region. For a time, Barlee opened a museum in Penticton to display his finds. It is now a brewery. At no point does he openly state that such treasure is there for the finding, but his maps and photographs offer too much incentive for pothunters to collect — unlawfully or illicitly — archaeological artifacts of the Syilx, Sinixt, and Smalqmix people.

What’s more, he relegates these people to some undefined Old West, now faded from history, with such writing as:

The once proud Similkameen have been drastically reduced in number, but the valley, especially beyond the travelled routes, is remarkably like it was a century or more ago … in many places it is still the west of the past, an almost forgotten yesterday when the Similkameen Indians held undisputed possession of this mountain valley.

Such descriptions don’t describe today’s Similkameen, and in no way describe a resurgent people reclaiming their land and actively patrolling, for example, the Arrow Lakes today to curb the illegal mining of the reservoir’s shifting foreshore for artifacts, and destroying the archaeological record in the process. The Indigenous people of BC’s interior aren’t a people of the past. Their historical places aren’t some equivalent of ghost towns.

You wouldn’t know it from Barlee, though. Listen to him describe the Boundary Country: “The Boundary region was not inhabited to the extent of either the Okanagan to the west or the Kootenays to the east and it is not generally recognized as Indian country today.” He goes on, in detail: “The most consistently occupied region was probably Christina Lake which had two major villages and at least a score of minor camps along its shores.” He then describes the main villages at the lake outlet, and notes that “Many artifacts have been recovered from both of these sites for years.”

Back when this book was new, I chased away a group of three treasure seekers as they dug into Chief Ashnola’s grave in central Keremeos. They left, but not without leaving a sense of entitlement and comments that “everybody does this.” And a shrug or two. Even at the time, I was sure they would return to resume their illegal plundering. People like that need no encouragement, even if it is just through a combination of romanticization and inference.

At least Barlee treats early settler culture in a similar fashion. His entries on O’Keefe Ranch and the Okanagan Mission are spectacularly brief. Even though Cornelius O’Keefe’s skill at using BC’s legal system to block Okanagan Indian Band access to the ranch’s grazing land, and even to acquire Okanagan Band lands for his own uses, lies outside Barlee’s scope, neither does he mention the Syilx villages that O’Keefe’s land sat upon or pushed aside. Nor does he mention the village and trail sites that the whole O’Keefe settlement at Spallumcheen continues to privatize and withhold from access.

Of the Okanagan Mission, Barlee repeats the old myth that it is “The oldest white settlement still standing in the Okanagan valley. Founded by an Oblate missionary, Father Pandosy, in 1859, it was from this headquarters that the Oblates ranged through the Okanagan country carrying the cross to the Indians.”

The date is off. Pandosy arrived in 1859, but he went to the north, near today’s Kelowna International Airport, where he camped at the house of a French Canadian and his wife, so that he could be near the Syilx winter village. It was a bad winter. He had to eat his horses. He chose his new site to the south to be near some better grass. It was also a major lake crossing for the Westbank First Nation.

In such a context, and in our time of reconciliation between First Peoples and settlers, what on earth is the point any more of mentioning it as a “white” settlement? Especially when the mission’s more difficult legacy, a complex story of old hurts and distrust around early residential schools attached to the Mission, isn’t mentioned. Granted, it’s not Barlee’s topic, but neither is “white” settlement. Barlee’s topic here is treasure hunting.

I have no doubt that Barlee had a deep regard for Indigenous culture. I also have no doubt that, as a man of his time, he saw it as a culture of the past.

Tellingly enough, the Indigenous sites that Barlee mentions were not occupied by Indigenous peoples at the time he wrote. He also appears to have left out all Indigenous sites in private “white” hands. Although some now openly display Private Property and No Trespassing signs, the unrevised book doesn’t mention this change. The village site he shows at Okanagan Falls, for example, is now adorned with a private house, the property bristling with Do Not Enter signs.

Barlee does, however, mention many Indigenous sites on Crown Land, or at least land with uncontested access. He also mentions at least two on Reserve land, land that it as private as any sites of “white” settlement. They include a village site east of Hedley and the reserve at the intersection of Green Mountain Road and Highway 3A, which is Barlee’s suggested site for a purported pre-British massacre of Spanish explorers. Sites of similar or greater interest on “white” property are usually not mentioned at all. Those that might hide artifacts, such as burial slides in the Similkameen, are noted on his maps. Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns in British Columbia needed a revision – a new and revised edition, not just a reprinting — to lay out the evolving legal and social contexts of these sites and the threats to them.

Here, too, Barlee’s treasure-seeking heart has allowed itself some universal liberty. He details every ghost town in southern BC and displays collections of artifacts found by metal detector and spade on their streets or under their sidewalks. Presumably, these artifacts of archaeological interest were found on private property, even if such sites sometimes lack any current claimants. One could do better than hint, passively, that it is all out there for the taking. Not that Barlee says it is, of course, but sometimes hints are enough.

*

Harold Rhenisch was raised in the grasslands of the Similkameen Valley and has written some thirty books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for The Wolves at Evelyn (Brindle & Glass, 2006), a memoir of German immigrant life from the Similkameen to the Bulkley valleys. His other grasslands books are the Cariboo meditation Tom Thompson’s Shack (New Star, 1999) and the Similkameen orchard memoir, Out of the Interior (Ronsdale, 1993). He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and has worked closely with the photographer Chris Harris on his Cariboo-Chilcotin books published by Country Lights: Spirit in the Grass (2008), Motherstone (2010), and Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2016), as well as The Bowron Lakes (2006), and he writes the blog “Okanagan-Okanogan: One Country without Borders,” from his home in Vernon. For seven years, he has toured the grasslands of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho while working on Commonage, a history of the Okanagan region set in its American context, highlighting the American history of Father Charles Pandosy and situating the roots of the Commonage land claim in the North Okanagan in American colonial practice in Old Oregon. Harold lives in Vernon.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

12 comments on “#752 Updating Bill Barlee”

I have been searching for the Spanish mound since I was seven, and love to hear your insights into bill Barlee and his life. I follow in his footsteps and my family knew his. If you would like to talk i would be honoured.

Regards

Clint morrish

Where did N.L. Barlee’s collection go after his passing? I wish there was a dedicated museum to Bill’s work, findings, and items. Great local history that needs to be kept alive.

I can’t say that I find this review very accurate or well written. Once again a modern “historian” judges the past by today’s standards of ridiculous political correctness. Bill Barlee was an interesting and entertaining historian who was instrumental in promoting our heritage in BC. Let’s honour him according to the context of his time, rather than by the idiocy of ours.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Ivan. I was going to share my thoughts in a post, but I no longer need to, as you’ve already said precisely what I was thinking.

I was quite disappointed in this review. At best, it is lacking appreciation for the temper of the gold rush and later 19th century era that Barlee is trying to recount — something that he does incredibly well in his Gold Creeks and Ghost Towns. More pertinent, though, is Harold Rhenisch’s sense of entitled rectification of our BC roots… I posit that the good and the bad should stand on their own as part of British Columbia’s heritage and not be painted over with a veneer of modernization and political correctness. To deprive the reader of his own faculty for judgement would essentially call into question the intelligence of the author’s audience. Should we also rectify the writings of Jane Austen while we’re ‘modernizing’ Barlee’s work?

The reports in this review that Bill Barlee essentially endorsed the plunder of old settlements and historic locations for artifacts, seems to me to run at odds with the point that Barlee went so far as to apologetically forbid Americans a subscription to his Canada West Magazine. This was due to what he perceived as too much wanton stripping and removal of historically significant items of local value, by pothunters from the States. He did not want his magazine to contribute to this, even if readership numbers might suffer as a result. Is this the act of a man who approves of the practice?

Thank you, Mike Stuart. In a similar vein, I’ve never forgotten one of Barlee’s editorials in Canada West Magazine where he lamented that American bottle diggers were taking pickup truck loads of Chinese ceramics and bottles from the dumps at Cumberland’s Chinatown back across the border with no objection from Canadian authorities or customs officials.

I would have to agree with Mike Stuart in this instance. I think the reviewer in an attempt to provide an update of Barlee went a bit too far — I had the same impression! Good point!

Note by Richard Mackie: Grahame Ware has had email troubles, so has asked me to post this comment on his behalf:

The Barlee/Ryga Connection. Thanks very much Harold Rhenisch for the good review … as usual! I wanted to mention an example of Bill Barlee’s long reach in the last three decades of the last century.

James Hoffman, retired prof at Thompson Rivers University and author of The Ecstasy of Resistance: A Bibliography of George Ryga (Toronto: ECW Press, 1995) relates that:

“For radio there was the CBC’s Bush and Salon series (a radio series produced by Don Mowat that recreated early Canadian life from letters, diaries, etc.), in which Ryga and researcher/ lorist Bill Barlee travelled to historical locations around B.C. to find material, resulting in a series of radio plays, one of which, Dreams are made of Gold Dust, was the basis for the stage work, Ploughmen of the Glacier.” (Source: <https://www.ucalgary.ca/lib-old/SpecColl/rygabioc.htm>

Ryga’s original title for Ploughmen of the Glacier was Two Men of the Mountain. He was indebted to Barlee for the wealth of material he unearthed regarding Volcanic Brown, who discovered Copper Mountain in Hedley, BC. Ploughmen of the Glacier examines the relationship between the rugged miner, Brown, and the retired journalist, Robert Lowery. The play was commissioned by Western Canada Theatre of Kamloops. Under the direction of Tom Kerr, it toured in April and May of 1976. Talonbooks published it in 1977, edited by Peter Hay. It is one of Ryga’s best plays.

Incidentally, Barlee had promised that Ryga’s house, which was used as an artist-in-residence venue for many writers over the years, would get a BC provincial cultural contribution of $100K to save it, but the grant was never made. Ryga’s friend Barlee had made the promise as the Minister responsible in Mike Harcourt’s government. Eventually it was sold despite the Herculean fund-raising efforts of Ryga’s protegé, Ken Smedley.

Thanks for your time,

Grahame Ware