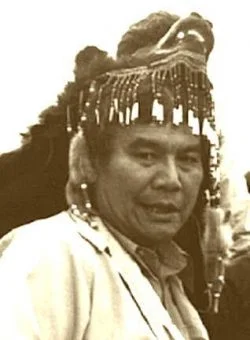

#746 An Indigenous advocate

The Fourth World: An Indian Reality

by George Manuel and Michael Posluns (foreword by Vine Deloria Jr., afterword by Doreen Manuel, introduction by Glen Coulthard)

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019 (first published by Collier Macmillan Canada, 1974)

$24.95 (U.S.) / 9781517906061

Reviewed by Chris Arnett

*

When I taught in the First Nations studies program at Malaspina University-College (now Vancouver Island University) in Nanaimo way back in 2000, I had to design a syllabus for a second year course called “First Nations, Racism and Colonialism.” This was my first teaching gig and I already had the perfect course text: George Manuel and Michael Posluns, The Fourth World: An Indian Reality, which I’d picked up in a used bookstore a few years before. There was nothing else like it. Inside the innocuous dark yellow cover was the first account I had ever come across that described the colonial history of British Columbia from an Indigenous perspective. Furthermore it connected the struggles of local Indigenous people to those of a global community of Indigenous peoples. I put in my book order only to learn it had been out of print for 25 years.

When I taught in the First Nations studies program at Malaspina University-College (now Vancouver Island University) in Nanaimo way back in 2000, I had to design a syllabus for a second year course called “First Nations, Racism and Colonialism.” This was my first teaching gig and I already had the perfect course text: George Manuel and Michael Posluns, The Fourth World: An Indian Reality, which I’d picked up in a used bookstore a few years before. There was nothing else like it. Inside the innocuous dark yellow cover was the first account I had ever come across that described the colonial history of British Columbia from an Indigenous perspective. Furthermore it connected the struggles of local Indigenous people to those of a global community of Indigenous peoples. I put in my book order only to learn it had been out of print for 25 years.

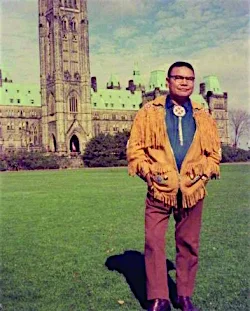

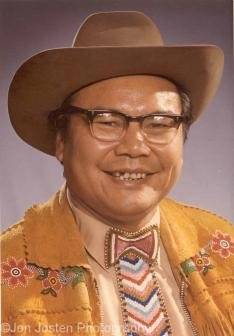

Re-issued by the University of Minnesota Press with a new introduction by Glen Coulthard and an afterword by George Manuel’s daughter Doreen Manuel, this classic 1974 text is now available to a new generation of readers. The Fourth World weaves an oral history of Secwepmec political leader, George Manuel (1921-1989) with the research and writing skills of Michael Posluns (born 1941) a Canadian journalist and researcher, who passed away in January 2020 in Toronto while I was preparing this review.

While both authors brought their particular skills to the project and described the writing of the book as a dialogue between them, it is George Manuel who tells the real story based on his own experience with church and government oppression of Indigenous people. A marvellous chronicle of the early years of the Indigenous political movements in BC and the simultaneous rise of a prominent activist, The Fourth World: An Indian Reality is made all the more poignant by Doreen Manuel’s references in the Afterword to a daily journal detailing her father’s trials and tribulations.

The opening chapters undermine received versions of BC and Canadian history by highlighting the differences between European and Indian ways of knowing and the fast-tracked colonization of the Canadian west in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Decades before Truth and Reconciliation, Manuel describes residential schools as “the perfect instrument for undermining both our values and our economic base” and “the perfect system for instilling a strong sense of inferiority” (p. 67). “Hunger is both the first thing and the last thing I remember about that school,” he writes, referring to the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Manuel’s initiation into political activism crystalized in 1959 when he became president of the North American Indian Brotherhood of BC, which led him to a career both on the local scene as Chief of the Neskonlith Indian Band (east of Kamloops), and also into the national and international arenas of Indigenous advocacy. There are episodes of great drama in Manuel’s recollections, such as when he confronted an Indian Agent at a tense reserve meeting after driving miles over treacherous mountain roads in an old Chrysler that could only manage steep mountain roads in reverse.

Manuel’s firsthand accounts of his dealing with priests, government bureaucrats, and others reveal the depths of ignorance, corruption, and racism that all early Indigenous activists had to confront and overcome. The Fourth World was very clearly sparked by the misguided assimilationist 1969 White Paper of the Pierre Trudeau Liberal government that met with wide opposition by Indigenous groups and leaders, including Manuel.

In the new introduction, Glen Coulthard describes The Fourth World as “unquestionably one of the core texts in the wave of red power literature that emerged in the tumultuous politics of the 1960s and ‘70s” (pp. x-xi). It is remarkable both for its rhetorical style and as an historical document far ahead of its time, conceived and written decades before major political events including several major Indigenous title and rights cases in the Supreme Court of Canada.

Still, not much has changed — witness the recent opposition of Wetsuweten hereditary chiefs over LNG pipelines in their territories, which is a key to the book’s continuing relevance. Indeed, Coulthard wonders why tell this tale at all, given that Manuel’s fight for Indigenous self-determination in the domestic and international spheres resulted not in liberation but in “further colonial subjection” (p. xxx). He suggests that the need for interventions “organized around political and cultural recognition” is one takeaway message from the book.

Indigenous people all around the globe are taking this initiative. As long ago as 1975, a year after the book came out, the Mount Currie Community School (now Xet̓ólacw Community School) opened in Secwepmec territory, the second band-run school in Canada and the beginning of a renaissance in returning Indigenous education to the local level. There is also a growing recognition of Indigenous rights among the greater settler population who were kept so long in the dark by received versions of history, and the attendant racism engendered by them. A powerful reminder of a time and place, The Fourth World is essential reading for anyone interested in the origins of the Indigenous rights and title movement in British Columbia.

George Manuel’s work as founder and president of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (1977-1981) led directly to the creation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, which was recently adopted by the British Columbia Provincial Government — who may, however, be at pains to enact it. During his work with the World Council of Indigenous People, Manuel recognized that all Indigenous groups throughout the world shared one important attribute — a spiritual connection to land. As he wrote,

All of our structures and values have developed out of a spiritual relationship with the land on which we have lived. Our customs vary as much as the different landscapes of the continent, but underlying this forest of legitimate differences is a common soil of social and spiritual experience.

It is, Manuel continues, in this spiritual relationship to land and place that a Fourth World emerges, “as each people develops customs and practices that wed it to the land, as the forest is [connected] to the soil… (p. 7).

Manuel and Poslun’s concept of a Fourth World was inspired by the revolutionary contexts of the 1960s, when countries in Africa and Asia rid themselves of colonial oppressors and created their own nation states, the so-called Third World. The Fourth World is different. It is a place of Indigenous people and their lands, and a space, a potential world, in which Indigenous values of sharing and respect for all things might still become universal values. That is, the Fourth World is an inclusive ideal not yet achieved. It will only be made possible by recognition of the rights and title of Indigenous people.

“The Fourth World is a vision of the future history of North America and of the Indian peoples,” write Manuel and Posluns. “The two histories are inseparable.” The scope of their vision is a Fourth World with a value system that, arguably, supported our species well for 99 percent of our existence and may once again be manifest. Unfortunately, what Manuel and Posluns wrote 36 years ago remains true today. The Indigenous world “is almost wholly dependent upon the good faith and morality of East and West within which it finds itself” (p. 6). And that is precisely the problem.

*

Chris Arnett is an author, artist, archaeologist, musician, historian, and heritage consultant who lives on Salt Spring Island and in the Vancouver area, where he is currently a sessional instructor in the Department of Anthropology at UBC. His parents, grandparents, and great grandparents instilled in him a keen interest in North American history and in the people and culture of his ancestral homelands of New Zealand, Cornwall, and Norway. He continues his ongoing self-directed and institutional ethnographic, archaeological, and sometimes musical research in British Columbia. With Annie York and Richard Daly, Chris wrote They Write their Dreams on the Rock Forever: Rock Writings in the Stein River Valley of British Columbia (Talonbooks: 1993, new edition 2019). He also wrote The Terror of the Coast: Land Alienation and Colonial War on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, 1849-1863 (Talonbooks: 1999), and he edited Beryl Cryer, Two Houses Half-Buried in Sand: Oral Traditions of the Hul’q’umi’num’ Coast Salish of Kuper Island and Vancouver Island (Talonbooks: 2008).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#746 An Indigenous advocate”

I knew Mickey Posluns first when he was working with George Manuel before the Fourth World was written and kept in touch with him until he died. I’ve continued to work in this area, and am still doing so. I’m glad to see these works being put together since it’s overdue to have a clearer understanding about the changes and currents that have buffeted Indigenous communities and leadership since 1965 or so…The chapters are not written yet, so no one can predict where things will be in the next few years, but I have identified where I think the assessments are not accurate, so will now weigh in, just to make the record more accurate.