#737 Canada vs Germany in Italy

The River Battles: Canada’s Final Campaign in World War II Italy

by Mark Zuehlke

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2019

$37.95 / 9781771622356

Reviewed by Richard Lonsdale

*

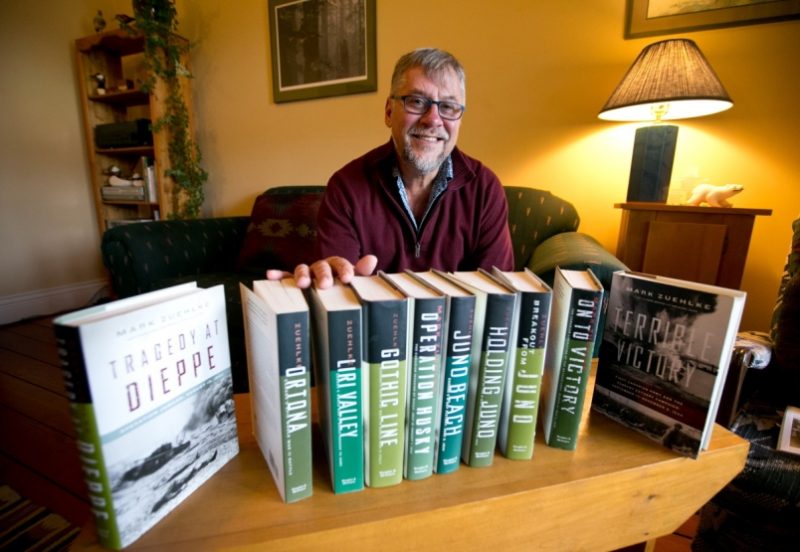

Twenty-five years ago there were very few popular book-length histories of the Canadians in the Italian Campaign of World War II. We can thank award-winning author Mark Zuehlke for rectifying this situation with the publication of his first four books on the subject: Ortona; The Liri valley; The Gothic Line; and Operation Husky. Collectively, they describe the hard-fought series of battles that began with the Allied landings in Sicily in July 1943 to the German retreat from the Gothic line near Rimini on the east coast of Italy in September 1944.

Twenty-five years ago there were very few popular book-length histories of the Canadians in the Italian Campaign of World War II. We can thank award-winning author Mark Zuehlke for rectifying this situation with the publication of his first four books on the subject: Ortona; The Liri valley; The Gothic Line; and Operation Husky. Collectively, they describe the hard-fought series of battles that began with the Allied landings in Sicily in July 1943 to the German retreat from the Gothic line near Rimini on the east coast of Italy in September 1944.

He has now written his fifth, and probably final, book on the Italian campaign, The River Battles, which describes the final phase of Canada’s role in Italy from late September 1944 to early February 1945. It is a remarkable volume filled with interesting detail about the battles.

In fact, the book almost did not come to be written. Zuehlke describes how he thought he would never write a book about this, the final period of the campaign. He had talked with his good friend John Dougan, a veteran of the Italian campaign, about such a book and Dougan had told him that he did not think there was enough material “to carry a book.” Moreover, when he had talked with historians at the department of National Defence’s Directorate, they had told him that, although there had been much hard fighting, there had been little ground won and, consequently, few strategic gains. But then, in 2014, an unexpected email message arrived, asking Zuehlke to be the keynote speaker at a conference on the liberation of the many Italian towns by Canadian regiments towards the end of 1944. He accepted the invitation and, as a result, “dug into the research,” and found “a wealth of material came to hand.” He saw that the Canadians had, in fact, played an important role in the Allied advance by keeping German forces pinned down in Italy, far from the more vital campaign of North West Europe. He knew then that a fifth volume could be added to the previous four volumes of what he called the “Canadian Battle Series books on the Italian campaign.”

The River Battles is written in a similar fashion to his many other books on World War II, of which there are now thirteen. He gives the reader a “you are there exposure” with vivid descriptions of the intense fighting which took place between September 22, 1944 and early February 1945.

Canada’s contribution to the offensive would be the 1st Canadian Corps, comprising the 5th Armoured Division with an attached infantry brigade, as well as the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, which had come into being when the war started in 1939. (The 2nd New Zealand Division was also attached to the 1st Canadian Corps.)

These two divisions had representation from all parts of Canada. More than twenty regiments including the three of the permanent force: Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, the Royal Canadian Regiment, and the Royal 22nd Regiment (the Van Doos). Representing British Columbia were the Seaforth Highlanders from Vancouver, the Westminsters from New Westminster, and the British Columbia Dragoons from the Okanagan Valley.

The land north of Rimini, where the Canadians found themselves in September 1944, levels out into the Emilia Romagna plain, which was described as “flat as a billiard table.” Crossing the plain and flowing into the Adriatic Sea were numerous waterways, including nine rivers, several canals, and many smaller streams.

After the Allied capture of the Gothic Line, the Canadian 1st Division went into a short period of rest, and many of the men believed that they had seen their last battle in Italy, as they assumed that the members of Canada’s other division, the 5th Armoured, with “its scout cars and carriers and Shermans and Churchills [tanks] would sweep into the plain, taking all before them.” After all, it was supposed to be good tank country.

Even senior commanders seemed oblivious to the fact that the plain was laced with a great many waterways, all of which had to be crossed. The commander of the Allied armies in Italy, British General Harold Alexander, had some concerns, but these were not based on the topography of the plain but on a shortage of manpower.

In June of 1944, seven divisions had been pulled from Italy to take part in Operation Anvil, the invasion of Southern France, and Alexander had been given in return only two and a half divisions to make up for the loss. He felt, however, that it was still necessary to keep forging ahead and not to allow the Germans to build strong defensive lines to the north. He believed that this strategy would prevent the Germans from transferring some divisions to Holland or North East France, where, by September, the German forces were retreating towards the German border.

On September 22, 1944, the first attack by the 5th Canadian Armoured Division was an advance from a bridgehead on the Marecchia River, with the British 5th Corps on its left and the 2nd New Zealand Division on its right. The initial goal was the Fiumicino River, about seven miles distant. In order to achieve the goal, the Canadians had to cross the Oso River, which lay between the Marecchia and the Fiumicino Rivers. After two days of very heavy fighting, only two and a half miles had been captured and the 5th Armoured was still 1,000 yards short of the Oso.

After further fighting, the Canadians reached the river, which was about fifty feet wide and had high dykes on each side. It took four days to establish a shallow bridgehead on the other side, incurring the loss of 30 soldiers and the wounding of 220.

The original plan had been to reach the Po River, some fifty-five miles away, in twelve days. It was now obvious that this unrealistic plan was not going to succeed. Colonel Jim McAvity later wrote, “there would be no mad tank gallop” to the Po. Instead, any advance would be a “grim and costly slog.”

The commander of the 1st Canadian Corps, Lieutenant General E.L.M. Burns, revised his plans. He now realized that, yes, the land was a flat plain, but across it flowed those many rivers, together with literally “hundreds of smaller streams, canals and irrigation ditches,” all of which would have to be crossed. The rivers all had high dykes to prevent flooding during the spring runoff or during the rainy season in the fall. In some cases, the dykes were as much as thirty-five feet high and created perfect defensive positions for the Germans.

A second major problem for the Canadians was the clay-like soil, which, Burns realized, when wet would turn the ground into a “morass capable of sucking men down to their knees and vehicles to their axles.” Moreover, it was predicted that “the fall of 1944 was to have many periods of high rainfall.”

Adding to the Canadians’ problems was the German Commander-in-Chief in Italy, Albert Kesselring, who was a brilliant defensive strategist. He knew he could not defeat the Allies, and with the loss of the Gothic Line he had no further established defensive positions; however, he also knew he could use the waterways to make life very difficult for the British 8th Army (of which the 1st Canadian Corps was a part), and perhaps slow it down until winter set in.

Zuehlke describes the Canadian advance in great detail. Apart from a much-needed rest period in November, the two Canadian divisions slogged their way northward, often with great difficulty, crossing the many waterways defended by the German forces. Sometimes, when there had been no rain, it was possible for the infantry to cross shallow rivers on foot. Other infantry crossings were made with 875 pound assault boats that had to be carried down the steep riverbanks by sixteen men.

It was a different story, however, for the tanks and heavy trucks, which required a bridge. In most cases, the Germans had blown up the bridges as they retreated, which meant that army engineers had to construct new bridges at appropriate places. Their work, together with that of the pioneer platoons, was absolutely vital. Often they used classic Bailey Bridges, but also Olafson Bridges or a simple Ark MkII bridge, which was constructed by replacing the turret on a Churchill tank with steel decking and ramps. The tank was then driven into the middle of the waterway, thus acting as the main support for the bridge.

On a number of occasions, the engineers’ work was in vain. Typical was the period October 25-26, when there was very heavy rain, which resulted in the Savio River rising to the point where it was eighteen feet deep. A Bailey Bridge and a floating bridge were both destroyed and washed away by the current.

The engineers often worked in extremely dangerous conditions. Zuehlke describes the efforts of Lieutenant John Walter Young and the 10th Field Squadron to install a floating bridge on December 11th. “Any movement on the dyke drew immediate mortar fire, which for one forty-five-minute period was continuous. Despite the fire, Young refused to withdraw … and continually rallied his men back onto the job.” For his actions, Young received the Military Cross. In part the citation read: “Lieutenant Young’s apparent contempt for danger and determination to complete his task was a great inspiration to his men.”

Many other acts of bravery are described throughout the book. For example, on October 15th, Sergeant Ed Ralph of the 48th Highlanders, when his unit was faced with finding a pathway through a minefield “decided to do the job alone. Crawling on his hands and knees, prodding the road with a knife, while being fired on by mortars zeroing in like snipers with rifles and the occasional 88-millimetre shell thrown his way to boot, Ralph calmly and deliberately worked away. He lifted twenty-two mines to clear a two-hundred-yard stretch of road.” For this feat, he was awarded the Military Medal. Two weeks later, Private Ernest “Smokey” Smith of the Seaforth Highlanders was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for bravery, for his individual stand against two German tanks and several German soldiers. He became the only Canadian Private in the Second World War to be so honoured.

Zuehlke also recognizes that hundreds of other men no doubt deserved recognition but, as happens in all wars, never received it.

By early January, the Canadians had successfully crossed several of the rivers and had reached the Senio River, where they would maintain a fairly static line until mid-February, when the order was given for all Canadian forces in Italy to move to the Netherlands.

The River Battles places a considerable emphasis on the stories of ordinary soldiers, but also informs the reader about the senior leadership of the Canadian Corps. In October 1943, British Lieutenant General Richard McCreary became the commander of the 8th Army. He recognized immediately that the structure of Canadian Corps “was quickly becoming dysfunctional.” The two Canadian divisions — the 5th Armoured and the 1st Infantry — were led by Major General Bert Hoffmeister and Major General Chris Vokes, respectively. Each of them was unable to get along with their corps commander, Lieutenant General E.L.M. Burns. Vokes wrote, “Burns seldom appears cheerful” and “his sad sack” manner repels subordinates and senior commanders alike. …he seems to lack the human touch … necessary in the successful command of troops.” General Alexander, the commander of all Allied forces in Italy, wrote “[Burns] is sadly lacking in tactical sense and has very little personality and no (repeat no) power of command.” McCreery sensed that “tension was thick, and everyone from the division commanders to the enlisted men appeared uneasy.”

Burns was temporarily replaced by Vokes, who was quickly replaced by Lieutenant General Charles Foulkes, on a permanent basis.

Zuehlke has been careful in this book to place the role of the Canadians within the greater context of the Allied armies in Italy. The reader is kept informed throughout the book of the overall successful strategy of forcing the Germans to keep fighting in Italy. Also included are some glimpses of the campaign from the German point of view, as Zuehlke makes use of the memoirs of Field Marshall Kesselring. The book would have benefited from having even more such references.

At the end of the book, Zuehlke calculates the number of Canadian casualties in the river battles to be 7,214, of which 1,276 were fatal. This figure amounts to more than a quarter of all Canadian Italian Campaign casualties — a significant number for four months of fighting. It was a high price to pay.

In summary, readers will find that The River Battles is an interesting account of a little-known part of the Italian Campaign, and it will be a valuable resource for future historians. It should be noted that there are times when Zuehlke’s extremely detailed descriptions may become difficult for some to follow easily. He has excellent maps at the front of the book, but it would have helped readers to follow the narrative of the individual battles of the campaign if he had supplied more localized maps along the way. This is a small quibble about a book that serves as a fitting conclusion to Zuehlke’s five books on the Italian Campaign, and is a worthy memorial to all those Canadians who fought in that inhospitable wetland.

*

Richard Lonsdale is a retired history teacher who lives in Armstrong. He received his B.A. (History and Political Science) in 1966, and his M.A. in History in 1973, both from the University of Victoria. His passion for history was inspired as a young child by his parents, and in high school by two outstanding teachers, Frank Duxbury and Graham Anderson. These teachers not only influenced his choice of career, but also provided him with exemplary role models for that career. Most of the thirty-three years that Richard taught history were spent at Pleasant Valley Secondary School in Armstrong, with a secondment from 1986-89 to Baden Senior School, on the Canadian Forces Base at Baden-Söllingen in Germany. While there, Richard was able to indulge his great interest in World Wars I and II by taking student groups from Baden-Söllingen to the battlefields in France and Belgium. After returning to Armstrong in 1989, he continued to study the two world wars, and in the intervening thirty years has led groups of students and others to the battlefields on a virtually annual basis. In 1999 he was a recipient of the Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence.

Editor’s note: see also Norman Fennema’s review of Mark Zuehlke’s The Cinderella Campaign: First Canadian Army and the Battles for the Channel Ports (Douglas & McIntyre, 2017) in The Ormsby Review no. 295, April 30, 2018.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#737 Canada vs Germany in Italy”

An outstanding review of a very important book for historians and for Canadians in particular. Thank you for a very informative review.

Comments are closed.