#718 Bare-knuckle boxing on ice

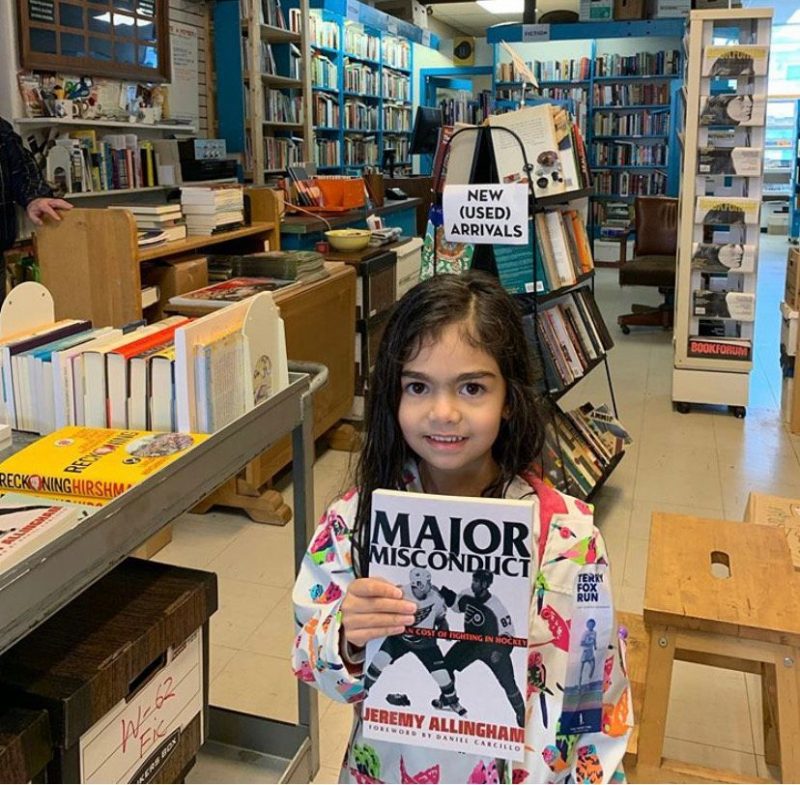

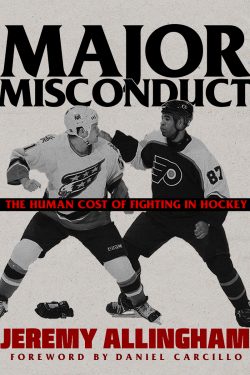

Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey

by Jeremy Allingham, with a foreword by Daniel Carcillo

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019

$22.95 / 9781551527710

Reviewed by Timothy Lewis

*

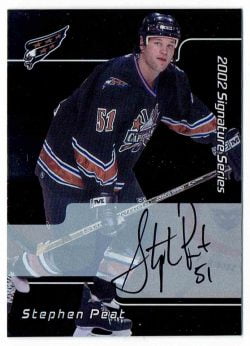

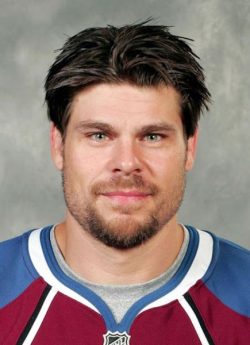

If you’re an ardent supporter of Canada’s recently deposed elder statesman of hockey commentary — Don Cherry — and his championing of fighting in the game, this is not the book for you! But if you’ve ever had qualms about hockey violence — fighting in particular — and the toll it takes on players, Jeremy Allingham’s Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey will both disturb and enlighten. The book details the heart-wrenching experiences of three hockey enforcers with small-town BC roots — James McEwan, Stephen Peat, and Dale Purinton — who now face life-altering mental and physical health challenges due to the unique role they played in the sport they love. The book also devotes a chapter to the historical origins of hockey violence, and briefly concludes with a hopeful vision for the game without fighting, but bringing the players’ troubling life stories to light is the greatest strength of Allingham’s Major Misconduct.

If you’re an ardent supporter of Canada’s recently deposed elder statesman of hockey commentary — Don Cherry — and his championing of fighting in the game, this is not the book for you! But if you’ve ever had qualms about hockey violence — fighting in particular — and the toll it takes on players, Jeremy Allingham’s Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey will both disturb and enlighten. The book details the heart-wrenching experiences of three hockey enforcers with small-town BC roots — James McEwan, Stephen Peat, and Dale Purinton — who now face life-altering mental and physical health challenges due to the unique role they played in the sport they love. The book also devotes a chapter to the historical origins of hockey violence, and briefly concludes with a hopeful vision for the game without fighting, but bringing the players’ troubling life stories to light is the greatest strength of Allingham’s Major Misconduct.

Allingham is no hockey “hater;” he describes his early minor hockey experiences with these words: “It was bliss. It was freedom. It was religion” (p. 15). Until recently, he was also an avid proponent of fighting; he was certain that it served an integral role in the game, as the threat of a good thrashing supposedly kept highly skilled players safe from violent attacks delivered by lesser lights. However, Allingham’s thoughts on hockey fighting changed suddenly, and unexpectedly, at a Vancouver Giants major junior game one evening. A heated fight broke out at the opening faceoff, and as the crowd roared its approval, Allingham was figuratively struck by the youthfulness of the combatants, and the highly questionable behaviour of the cheering fans. “[T]hese were a couple of baby faces . . . [aged 16 and 17]. We, the crowd, were thousands of fully grown adults (with plenty of kids mixed in) cheering, even demanding, that two children beat the shit out of each other with bare fists on ice” (p. 17). As Allingham writes: “I had an overwhelming feeling that what I had just witnessed, and implicitly supported, was deeply wrong” (p. 18). Shortly thereafter, he began to investigate hockey fighting as part of his work as a CBC journalist. That, in turn, produced Major Misconduct.

The three player stories at the heart of Major Misconduct are each gripping in distinct ways. I will leave specific details to readers of the book, but Allingham’s profiles of McEwan, Peat, and Purinton also highlight important similarities. All three men were born or raised in small-town British Columbia: McEwan in Terrace, Peat in Princeton and Langley, and Purinton in Sicamous. All three became enthralled with hockey at a young age, and were encouraged by their parents to pursue the sport. And all three, thanks to a combination of physical size, intimidating demeanour, and a passionate drive to succeed, became high profile hockey fighters by the time they were in junior. Fighting in virtually every game — often multiple times per game — and delivering bone (and head) rattling body checks was their specialty. Each man embraced the role with enthusiasm and pride, and can still speak of it in positive terms. For example, James McEwan states:

I love the expression of the warrior spirit that’s in the fighter…. It always did something inside of me …. Looking back at it now,… [Fighting] was like a drug, and I was addicted to it (p. 34).

But addictions come with negative consequences, and hockey fighting, or bare-knuckle boxing on ice as Allingham terms it, is no exception. Yes. Bare-knuckle boxing on ice! The author’s repeated use of that phrase is jarring for the reader; but that is the point. Fighting is such a widely accepted part of Canadian hockey culture that many become automatically and aggressively defensive when any suggestion is made that it should be eliminated from the game. In that line of thinking, to oppose fighting is equivalent to opposing hockey in its entirety, and its hallowed place within the nation’s culture. That, in turn, triggers passionate, oft-times, hateful responses. Indeed, as soon as Jeremy Allingham went public with his new thinking on hockey fighting, first via tweet and later through his journalistic work, he received a torrent of angry, homophobic and misogynistic-themed personal attacks on social media (pp. 20-21). In using the term bare-knuckle boxing on ice, Allingham seeks to counter such knee-jerk responses and confront the reader with what a hockey fight literally is: a bare-knuckle boxing match on ice that frequently features young men who are still not old enough to vote. As bare-knuckle boxing is illegal in North America in virtually every other context, Allingham’s choice of words forces the reader to see a stark reality that is too often accepted as just part of the game’s unique culture.

No matter the turn of phrase one chooses to describe their actions, the serious mental and physical health woes experienced by many hockey fighters are now impossible to ignore. Although it brought each man a brief moment of wealth and fame, Allingham makes clear that serving in the role of hockey enforcer has cost James McEwan, Stephen Peat, and Dale Purinton dearly. By the time they reached the professional ranks, the repeated physical abuse they delivered, and received, resulted in multiple hand, head, and shoulder injuries that caused, oft-times, crippling pain. Not wanting to step away from their role as defender of their teammates, not to mention their sole source of income, the players began to self-medicate with alcohol and prescription and/or street drugs. But there was no escape from the pain, and substance abuse was added to their litany of difficulties. Each man has since made progress with their addictions, and is moving past the consequences that arose from them, including homelessness, alienation from friends and family, and criminal acts resulting in jail time. Yet many of the mental and physical symptoms arising from their years as hockey fighters persist: severe headaches, anxiety, depression, delusions, uncontrollable fits of rage, and suicidal thoughts. Most worrisome, those are all symptoms closely associated with the incurable brain disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE.

While much remains to be learned about CTE — currently, it cannot be confirmed until after an analysis of brain tissue is completed following a patient’s death — what is known is deeply disturbing. A consequence of repeated brain traumas, CTE results in lost neurons, scarred brain tissue, and a general atrophying of the brain that causes the symptoms outlined above, and increases the likelihood of developing Parkinson’s disease and dementia. Even more disturbing, several former hockey enforcers who have since been confirmed or suspected of having CTE – Rick Rypien, Wade Belak, Derek Boogaard, and Steve Montador — have died before the age of 40, often at their own hand (pp. 99-107).

As its persistence clearly contributed to the mental and physical struggles McEwan, Peat, and Purinton now deal with, Allingham devotes one chapter in Major Misconduct to an historical investigation of hockey fighting (pp. 159-184). The chapter sheds some light on the matter, but Allingham does not make use of the best available academic research; he thus fails to fully flush out the historical roots of why so many hockey supporters, men in particular, have insisted that fighting, and other forms of violence, are integral to the sport. Allingham does cite several hockey historians who reveal that fist fighting was not that common in early, organized hockey, but other forms of violence were. That is the greatest weakness of the chapter: its failure to document just how violent early hockey truly was, and the justifications used to defend it.

For example, no mention is made of the on-ice deaths of Alcide Laurin, in 1905, or Owen “Bud” McCourt, in 1907, both of whom were killed by deliberate blows to the head from an opponents’ hockey stick. Great public consternation was expressed in the aftermath of those assaults, and in each instance, the assailants — Allan Loney and Charles Masson — were charged with murder. Tellingly, however, both Loney and Masson had the charges against them reduced to manslaughter, and were subsequently found not guilty. Thus neither faced any consequence for their violent actions other than the relatively short time they were held in custody awaiting trial. Even more significant is the rationale the juries used to justify acquittal in each case, which stemmed largely from how many Canadians viewed hockey at the time.

Organized hockey was led and popularized by upper middle class men, and their initial attraction to the sport arose, at least in part, from concerns about two realties of middle class life in the industrial capitalist era. First, the changing economy saw men spend more time outside the home than ever before. Consequently, male children were increasingly left under the care of either their mothers or their female public school teachers. That sparked fears that the next generation of men would be too feminized. Many upper middle class men were also dissatisfied with the physically inactive, office-bound nature of their work lives, which supposedly was making them go “soft.”

Fearful of that combination of cultural feminization and “over-civilization,” many upper middle class men turned to violent, “manly” sports, as a means to revitalize their physical strength and endurance, and restore their traditional sense of manhood. Hockey was chief among the manly sports embraced by Canadian men, as playing hockey demanded high levels of toughness and a willingness to accept good degrees of violence. Arthur Farrell, a member of the 1899 Stanley Cup Champion Montreal Shamrocks, encapsulated the thoughts of many when he wrote: “hockey is a game for men, strong, full-blooded men. Weaklings cannot play it.” Moreover, as Stacy Lorenz and Geraint Osborne note in a recent academic paper,

It was widely believed that combative sports … taught perseverance and competitiveness among young men, all of which could be applied to the battlefield. As a result, “manly sports” were regarded as essential to nation-building, imperial service, and, when necessary, colonial war.”[1]

No surprise then that the defence lawyer in Allan Loney’s manslaughter trial reminded the all-male jury members that: “the battles of the British Empire were won on the playgrounds of Great Britain.” He then pivoted to “the splendid record made by the young Canadians who had served the Empire recently in South Africa” [in the Second Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902], whose “remarkable strength and endurance . . . was developed in the manly sports of this country, such as hockey and lacrosse.”

Finally, as all hockey participants were fully aware of its dangers, and as his client had merely engaged in manly self-defence in what was a particularly violent contest, Loney’s lawyer concluded that: “when a life was lost by misadventure in manly sports it was excusable homicide.”[2] Allingham does provide analysis of a much later court ruling — Jobidan v. the Crown (1991) — that very much reinforced the legal principle that only limited legal consequences should result for those who engage in acts, such as hockey fights, that are considered customary norms, but he misses out on the even deeper historical roots of that principle (pp. 179-184).

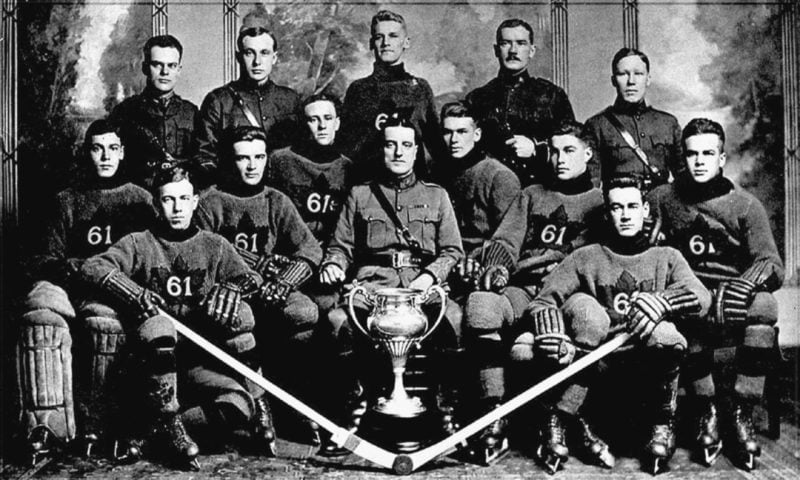

While not all commentators at the time of the Loney and Masson trials agreed with their acquittals, or the idea that the benefits of manly sport outweighed the occasional act of extreme violence, many did. And the link between the manly sport of hockey, the state of Canadian manhood, and the status of the nation as a whole was further solidified with the onset of the Great War of 1914-1918, which saw a new generation of young hockey players spark an unprecedented wave of Canadian nationalism thanks to their performance in battles such as the iconic Vimy Ridge.

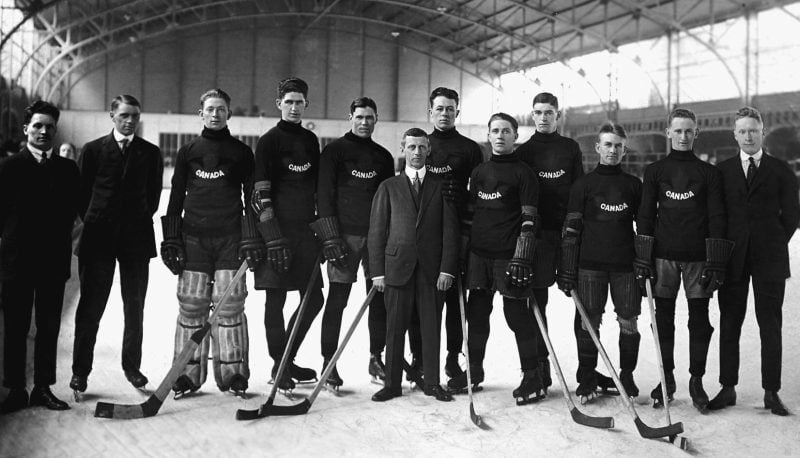

The potent bonds between nationalism and the manly sport of hockey were further reinforced with the debut of international hockey competition at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, where Canada easily claimed gold thanks to the dominating efforts of the Winnipeg Falcons, a team composed entirely of First World War veterans.

From that time on, Canada’s [a.k.a. Canadian men’s] performance in international hockey became both a vessel for Canadian nationalism and a test of the state of Canadian manhood. All this helps to explain thoughts such as those expressed by a Toronto Globe reporter in December 1947. As serious questions arose as to the quality of the RCAF Flyers, Canada’s hockey representatives at the upcoming 1948 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland, he wrote that “it was Canada and not the RCAF or the CAHA which was at stake in the Olympics.

Major Misconduct thus fails to explicate just how powerful the linkages between masculinity, expressions of Canadian nationalism, and violent manly sports like hockey truly were. Jeremy Allingham, no doubt, had to produce the book by a certain deadline, all while carrying on his regular work at the CBC, so it is understandable that he could not immerse himself in the latest academic work in the field, but he missed an opportunity to provide his readers with the full historical context of Canada’s long embrace of hockey violence. That context explains the deep-seated defensiveness that is evident whenever Allingham, or others, challenge hockey’s status quo, as to challenge hockey, especially its more violent components, is to challenge a certain conception of Canadian masculinity, and even the health of the nation as a whole.

A fuller examination of past hockey violence would also have assisted Allingham in identifying how and why fist fighting became noticeably more common in hockey. After suggesting that it was relatively rare in the early decades of the game, he notes that fighting was fully normalized by the 1920s. It remained a common practice for decades to come, and reached new and frightening levels with the rise to prominence of the infamous Philadelphia Flyers teams of the 1970s (aka the Broad Street Bullies) (pp. 167-171). However, given the high profile deaths of hockey players due to stick assaults in the first decade of the 20th century, and the countless other serious stick attacks at the time that did not prove fatal, it seems logical to suggest that the fist fight, or bare-knuckle boxing on ice, became a more common hockey tactic in large part because it retained the element of manly aggression so prized at the time, but was less deadly than stick assaults on un-helmeted heads. That too is a historical insight missing in Major Misconduct.

Major Misconduct ends on a hopeful note. James McEwan, Stephen Peat and Dale Purinton are portrayed as making strides in terms of coping with their physical and mental challenges, and the reader is also provided with convincing evidence that fighting is rapidly declining in frequency at both the professional and junior levels. This owes to key rule changes, the launching of recent court action that holds the NHL responsible for the violence it has tolerated/promoted over the years, and the threat of even more legal challenges to come. Thus the McEwan, Peat, Purinton cohort may be the last generation of hockey players to suffer so greatly as a result of bare-knuckle boxing on ice (pp. 227-237).

Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey is a must read for any hockey fan who wants to see the game grow and develop without the necessity of inflicting life-altering heath issues on its participants. While it fails to provide full historical context for the origins and long-standing defence of fighting in the game, Major Misconduct, thanks to its powerful personal profiles of McEwan, Peat and Purinton, makes a convincing case that the ongoing evolution towards the end of bare-knuckle boxing in hockey must reach its conclusion sooner than later. As Allingham notes: “[O]nce fighting is gone, it’s true, hockey will never be the same. Because hockey will be less violent. Hockey will be safer. Hockey will be better” (p. 239).

*

Timothy Lewis is Professor and Chair of History at Vancouver Island University in Nanaimo. Among the courses he teaches are several focused on the emergence and development of professional sports in Canada, and the place of hockey within Canadian identity. His research work is focused on the history of 19th and 20th-century New Brunswick, portions of which have been published in two articles in Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Stacy L. Lorenz and Geraint B. Osborne, “‘Nothing More Than the Usual Injury:’ Debating Hockey Violence During the Manslaughter Trials of Allan Loney (1905) and Charles Masson (1907),” Journal of Historical Sociology 30:4 (December 2017), p. 710.

[2] Lorenz and Osborne, p. 710.