#712 Okanagan verse and jazz

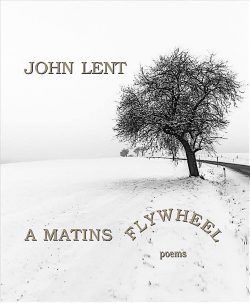

A Matins Flywheel

by John Lent

Saskatoon: Thistledown Press, 2019

$20 / 9781771871914

Reviewed by Trevor Carolan

*

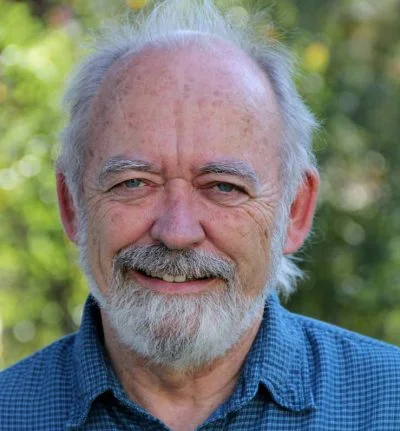

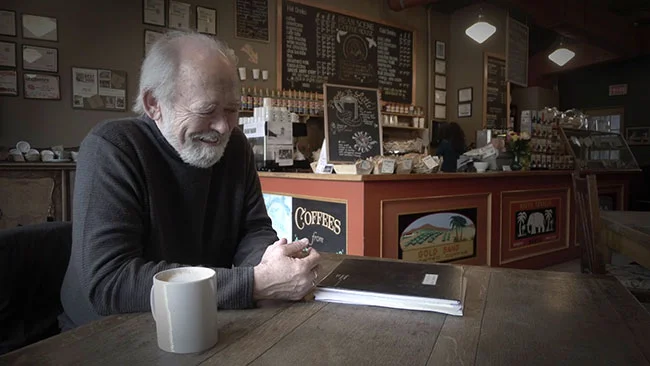

John Lent, the veteran BC poet, writes from Vernon where he has taught at Okanagan College and performed as a jazz artist for years. Within the literary community, he has long been appreciated for his contributions to the tribe, and his output has been quietly significant with nine books of poetry and fiction, and a volume of writerly conversations with the esteemed, late Robert Kroetsch. En route he has been nominated for awards and taught or as served in writer-residencies at a number of top-drawer arts programs and colonies. For forty years he’s paid the dues, working from a generally overlooked region, and as this latest edition confirms, in an enterprise where longevity is dependent on both wisdom and perseverance, in these shifting times he’s a poet who is still in the game for keeps.

John Lent, the veteran BC poet, writes from Vernon where he has taught at Okanagan College and performed as a jazz artist for years. Within the literary community, he has long been appreciated for his contributions to the tribe, and his output has been quietly significant with nine books of poetry and fiction, and a volume of writerly conversations with the esteemed, late Robert Kroetsch. En route he has been nominated for awards and taught or as served in writer-residencies at a number of top-drawer arts programs and colonies. For forty years he’s paid the dues, working from a generally overlooked region, and as this latest edition confirms, in an enterprise where longevity is dependent on both wisdom and perseverance, in these shifting times he’s a poet who is still in the game for keeps.

A Matins Flywheel is a prose-poem work that draws heavily on autobiographical detail. With his academic credentials Lent has also published critical articles on a series of challenging writers: Mavis Gallant, Sheila Watson, Malcolm Lowry, Kristjana Gunners, and Bob Kroetsch, among others, so there’s a depth of professional know-how in his tool-kit that he calls on repeatedly as well. One notes this because Matins is a work that ruminates on the poet’s own archival memory. Lent, again, plays jazz and this most improvisational of all modern art forms rests on the knowledge of prior modes and figures cut by other, typically older, artists who have inspired a performer’s current work. The parallels with literature hold, and when added to Lent’s personal life recollections, the result in this case is an ongoing practice in which he composes 37 “Matins” or morning prose-poem meditations spanning a period from April 2014 to May 2017; thus is shaped the mainframe of his book. Without any sense of self-conscious display, what unfolds from the first mention of Botticelli, Rembrandt, and Reubens, with a nod to Shelley the Romantic, is an acknowledgment firstly of mastery — that there is such a thing as worthiness that can be aimed for in an adult life, and in the arts at least, that can survive the wall of crap that too often passes easily and uncritically as “the new.” Lent has been around long enough to have weathered three or four of these over-hyped waves.

With his second entry, written from Long Beach in late fall, Lent informs us that the idea of “new” still does have meaning for him and that these matins aren’t simply the grousing of another aging bard. Rather, Lent shares that he has survived a quadruple heart bypass operation; he walks upon the sands literally as a new man — a realization that floods his consciousness “with bright wonder you almost have to squint into to survive it is so beautiful. You almost wince from it. A kind of pain.” Musicians call this peculiar form of sweet pain the Blues. Slide-guitarist Mississippi Fred McDowell once said the purpose of the Blues is to play right through the pain until we feel satisfied, and the nature of this satisfaction inspires a kind of gratitude. What strikes one in reading Lent’s meditations is how close his own conclusions echo the old blues masters’, moving beyond “enclosures caused by the mind … dysfunctional loyalties, empty gestures of love instead of love itself,” and that in leaning into this more authentic measure of worth, “We are truly blessed.”

Oddly enough, in the next meditation it is the virtues of “praise and gratitude … these old Catholic words” that come to haunt him — with echoes of his Edmonton boyhood growing up in a culture where he knew definitively what he was here for. Life moves on though, and from his St. Agnes Parish boyhood he has moved metaphorically from chorus to chorus, enjoying a reasonably privileged, jockish passing of days. Yet life is transformational, and having had “a glimpse and a feel for the end of things … a kind of darkness I had never imagined before,” incongruously while walking his dog one November morning in Vernon the poet finds himself on his knees intoning to himself the knowledge of what the jazz-man inside him might understand as confirmation of the changes, enunciating “… that’s what I’m here for: to love and acknowledge love, and praise and acknowledge the loves of the body, too, the elements, the micro-presences of whatever we used to mean by words like god.”

Through his reading of other writers and listening to the sounds of others yet, Lent reveals his lengthy interest in ways of reinventing the world, of being overwhelmed by the world. John O’Donohue and his Anam Cara with its investigation of the Celtic Renaissance inspire Lent in Matins #5; for with the Celts, he avers, “there was no distinction between landscape and subjectivity.” And there he is next, running the dog, encountering the divine in ordinary life, in ordinary mind. One thing leads to another. Then it’s Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations as a kind of “metafiction,” and a refrain from pianist Bill Evans’ rendition of “My Foolish Heart” has him contemplating life’s tapestry of mysteries that in its unfolding grace braids the many into the One, the One into the many. Declaring his allegiance to a litany of accomplished artists — Wallace Stevens, Baudelaire, Joe Lovano, Dylan Thomas, Lou Reed, Richard Ford — the poet displays the stuff of his “internal hard drive.” Fragmented, episodic, but joined by a sense of awareness, Lent’s walking-about-the-town meditations and his inspired-by-mentors epiphanies serve as the raw materials of what he believes “lifts the heart” (#18), for on viewing a hundred year-old maple being felled by professional gardeners, he realizes at the age of sixty-eight that his father had lived only a year longer. That kind of lift; that kind of real.

It’s in the 34th epistle with a note on Lent’s reading of Patti Smith’s M Train at 3:30 am that, consciously or not, his purpose becomes clear. “Her beautiful meditations” remind him of Ray Carver — no stranger to western Canadian readers. “I’m going to remember everything” he recollects of Smith’s writing, “and then I’m going to write it all down.” Written four months later, his 35th Matins echoes Smith’s cadence, vernacular descriptive style, and sensory observations. For Lent, it arrives as a memory of his Edmonton adolescence with scurrying people at Pigeon Lake, laughter, fragrances — no East Coast urban pastiche, but a western Canadian approximation. He’s become cognizant of the nature of his own soloing.

A documentary TV program on James Baldwin leads to speculations on contemporary America’s culture of “violence, fear and hatred” that unlocks a riff on his jazz trumpet-playing father’s sojourn in New York city, studying there and listening to artists like Billie Holiday and Dexter Gordon at night. Perhaps it’s no surprise that Thomas Merton, who rose as an important Catholic mystic teacher during this similar period, finds a niche in Lent’s thoughts. The poet’s own Catholic growing up years percolate through this volume — scraps of Church Latin, litanies of sacramental images and saints’ names, and little wonder this continues to inform his life and work as a substrate of his life’s experience. The bridge to other influential culture-shapers, if not decision-makers, from those years leads inevitably through music and references to golden-age folkie icons like Ian and Sylvia, Josh White, Odetta, Phil Ochs, Gordon Lightfoot, and Bob Dylan. In D.H. Lawrence’s phrase, these were names that were “the voice of [Lent’s] education.” And as the folk music scene morphed into a courageous role as an arm of the American Civil Right Movement of the 1960s, “all that slow, painful growth that required careful but brutal change” (#37) is remembered and felt again too, as if it were a perpetual collage, the bread of his life, a unified field of experience presenting itself: hoc est enim corpus meum. If altar-boy memory serves, This is my body.

The book’s second section, And Its Accompanying Flywheel, allows the jazzer inside Lent to flourish. The form is a little different; however, the pace and expressiveness work a similar groove to the Matins. “Your Father’s Beat,” written in Hermann’s Jazz Club in Victoria, glides on the band sounds in homage to tenor-sax boss Dexter Gordon and prompts a loving and searching memory of his father’s years toting his horn while a student at Columbia in 1950-51. With a line like “the way you blew yourselves through the topaz charcoal notation of those New York nights … this song we’ve braided together up in the blue air…” reveals Lent himself still has the chops at a time when inconsequentiality rules the MFA school poetry roost, and mortality has clearly been rooting around this man’s soul.

John Lent’s new work is worthy of examination. With its commitment to examining the conditions of our existence, these are an Okanagan Matins for a fragile age. Lent is not done yet.

*

Trevor Carolan usually writes from Deep Cove, North Vancouver, but he emailed this book review from Kanpot, Cambodia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#712 Okanagan verse and jazz”