#708 Make Rome great again

Possess the Air: Love, Heroism, and the Battle for the Soul of Mussolini’s Rome

by Taras Grescoe

Windsor, Ontario: Biblioasis, 2019

$22.95 / 9781771963237

Reviewed by Angela Clarke

*

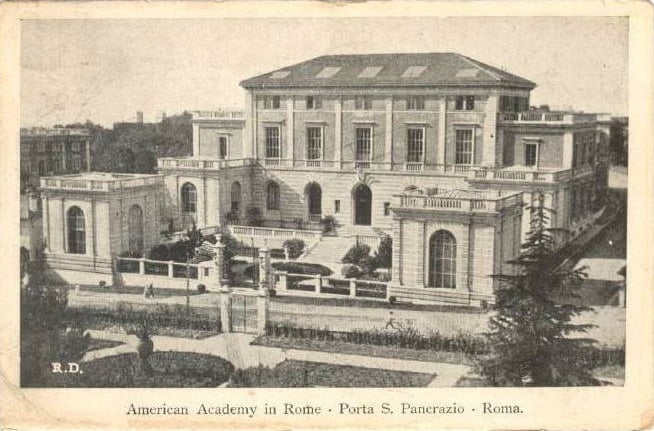

Taras Grescoe’s Possess the Air: Love, Heroism, and the Battle for the Soul of Mussolini’s Rome is a timely non-fiction study of populism and historical responsibility. Set in Rome during the Mussolini years (circa 1920-1945), this nonfiction book deftly documents the rise and fall of Il Duce and the fascist movement he created. While the story of fascism’s rise is the catalyst to this novel, Grescoe offers an unusual vantage point from which to assess Benito Mussolini’s firm hold over Rome: the American School at Rome, a lofty watchtower from which to spectate the unfolding of Mussolini’s regime.

Taras Grescoe’s Possess the Air: Love, Heroism, and the Battle for the Soul of Mussolini’s Rome is a timely non-fiction study of populism and historical responsibility. Set in Rome during the Mussolini years (circa 1920-1945), this nonfiction book deftly documents the rise and fall of Il Duce and the fascist movement he created. While the story of fascism’s rise is the catalyst to this novel, Grescoe offers an unusual vantage point from which to assess Benito Mussolini’s firm hold over Rome: the American School at Rome, a lofty watchtower from which to spectate the unfolding of Mussolini’s regime.

The American School itself is inhabited by elite academics and intellectuals as well as the children of America’s privileged. They are brought together to immerse themselves in, study, and imbibe the ancient ruins that are a living testament of the greatness of the Roman past. The American School at Rome, a bastion of entitlement, is an excellent setting for this story. It enables Grescoe to summarize and clarify the two fundamental truths regarding the perception of Italy and the people of Italy commonly held among the well heeled and elite of the time. These truths are two conflicting co-existing viewpoints, seemingly incongruent, held by Americans and Europeans until the 1970s.

The first truth was that the ancient past of Italy was the embodiment of taste and learning and that by living among its ancient ruins one could seek to comprehend, if not even transcend time to learn, the greatness of Rome. The art, architecture, and archaeology of this Rome could be bought at a price and taken back to America to become a monument to the great families who had the wealth to purchase it. Their collections still populate the great museums of the United States and are a visible reminder of the power and privilege of the great monied families of the first half of the twentieth century.

The second truth, seemingly contradicting the first, was the deep disregard and even distain and prejudice that Americans maintained for the “unwashed” Italian peasantry. Grescoe notes that American elites were coming to Rome en masse to buy art, walk among the ruins, and transform institutions such as the American School into rarified centres of classical learning for the rich and powerful and members of the academy. But the freedom to come and go from Italy enjoyed by American elites in Rome was not reciprocated. Despite Americans availing themselves of the charmed world of Italy’s cultural patrimony, simultaneously academic and governmental institutions in their own country actively restricted Italian immigration. An act of 1924 restricted the number of Italians allowed into America at 6,000.

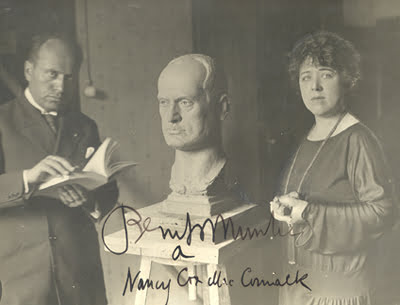

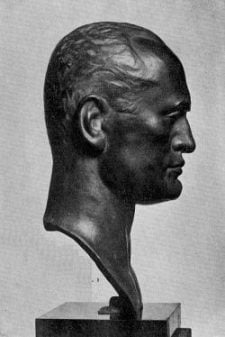

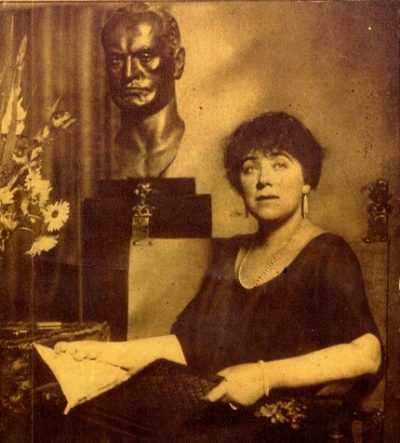

The setting of the American School of Rome allows Grescoe to unveil further fascinating revelations. First, the degree to which classical studies were part and parcel of elite culture. The school was the preserve of the privileged Americans; a place where an educated and monied New World elite could study and interact with European aristocrats. From this perspective one can see how luminaries and literary lions such as Thornton Wilder, the sculptor Nancy Cox-McCormack, George Bernard Shaw, and our main character the writer Lauro De Bosis studied while joining the rich and privileged for teatime and literary salons.

Second, Grescoe reveals that the American School was funded by wealthy financial institutions, specifically J.P. Morgan, and that the administration of the school was directly connected to the board of directors of this financial house. Even more, J.P. Morgan supported Mussolini’s rise both spiritually and financially, giving him millions to fund his endeavours even while actively expressing reservations regarding Mussolini’s behaviour. Concern was voiced increasingly by the J.P. Morgan administration that Il Duce was becoming unruly, aggressive, and unnecessarily expansionist — and yet the money continued to flow. Finally and most potently, Grescoe reveals how academic scholarship in the fields of archaeology and history supported the political ethos of Mussolini’s regime. Grescoe dispenses with the notion that the American School was a paragon of academic objectivity; in fact, it was politically allied with Mussolini. Grescoe demonstrates brilliantly how Mussolini courted scholars, and in turn how scholars courted Mussolini to work together to restore the greatness of Rome and support the growth of his power.

Grescoe’s revelation of American School’s enthusiasm for Mussolini is insightful. He shows how the school aligned itself with Mussolini’s politics. It benefited greatly from this alliance and Mussolini received academic cachet and respectability for his ambitions. For both, Rome itself was a projection and a dream. Together they envisioned that Rome under Mussolini would resurrect the Classical Age that reached its powerful apex under the leadership of the Emperor Augustus Caesar. Grescoe offers an effective case study of the use and abuse of history: foreign and Italian scholars alike at the American School published academic works that employed Roman antiquity to reinforce and approve of Mussolini’s ambitions.

However, as Grescoe notes, while Mussolini embarked on a resurrection of Rome’s grandeur, focusing on architectural restoration, development, and excavation of ancient monuments, his work was so greatly overextended and rapidly executed that much of his building plan never reached the quality of the ancient Roman original. In fact, many of his projects had a detrimental effect by exacerbating the existing instability of many of the ancient ruins in Rome, Ostia, and Pompeii.

Possess the Air is well-paced and rich in historical insights from this period. Grescoe describes Mussolini’s rise and his increasing hold over Rome in a leisurely manner that seems to mimic the tranquility of the affluent Americans who studied at the school and strolled in the sunshine through Rome’s Janiculum, the ancient and affluent district of the city. The turn of the tide against Mussolini is described in a more staccato pace, while his fall from grace, after he makes his claim on Egypt, is frenetic. Grescoe describes this deftly. True to form, Mussolini employed the scholarly research of Egyptologists to reinforce Rome’s aggressionist policies against Egypt, by claiming that Rome had always been a major formative influence in the splendour and power of Egypt, rather than the reverse. Mussolini’s aggressive expansion into Africa resulted in a slow realization in the court of popular opinion that his leadership was neither virtuous nor the embodiment of his magnanimity. By the time Mussolini allied himself with Hitler, his perception as a great strong man and worthy successor to Augustus Caesar had lost its momentum and believability. Although Mussolini celebrated the 2000th anniversary of the birth of Augustus in September 1937 at great expense, the allure of his regime was over, as was American financial support for his policies — and eventually also the American School’s blind support.

There is much to this story. While the life of a central figure was deeply affected by Mussolini’s rise and fall, Possess the Air is much more universal than can be conveyed by the experiences of a single life. Lauro De Bosis (1901-1931), the hero of the story, was the former director of the American school in Rome and its New York City equivalent, the Italian American Society, which, as Grescoe notes, was used by Mussolini to facilitate fascist expansion into America. Originally a supporter of Mussolini, De Bosis – whose mother was a New Englander — became an antifascist activist and finally a martyr to the cause by learning to fly an airplane specifically to deposit anti-fascist flyers over Italy, a mission that led to his death.

While De Bosis is a noble figure, the story is not so much about his life as about historical responsibility, and what occurs in its absence. Grescoe effectively breaks through our illusions of true historical objectivity, and in the process reminds us that in times of change, turmoil, chaos, populism, and polarity, any essence of objectivity is quickly dispensed with, even in the institutions of academia, where we expect to find it the most. While the message of Possess the Air is universal and pertinent, discerning readers will find in it a mimic of our times. For the purposes of this story it just happens to take place in Rome under Mussolini.

*

Dr. Angela Clarke is Director of the Italian Cultural Centre, Vancouver, and also Curator of Il Museo there. Her academic specialties include women, religion, and the domestic decorative art of Italy. Her interest in Italian material culture focuses on ceramics, textile, and mosaic. She has written about the material culture of the Italian Renaissance, especially Italian maiolica ceramics and the female-oriented arts and crafts traditions. She has curated the work of contemporary Canadian and European artists and is author of two museum catalogues: Heroine of A Thousand Pieces: The Judith Mosaics of Lilian Broca, and Family Lines: Lesbian Family Heraldry, An Achievement of Arms.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster