#657 Government House calling

The Lieutenant Governors of British Columbia

by Jenny Clayton, with a foreword by Janet Austin

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2019

$26.95 / 9781550178647

Reviewed by Patrick A. Dunae

*

The Office of the Lieutenant Governor is perhaps best known to the public for its pageantry. But it has an important constitutional function. It was created under the British North America Act, which established the Dominion of Canada in 1867. Under this legislation (now known as the Constitution Act, 1867), each province is provided with a viceregal official who represents the Crown. These officials are formally appointed by the Governor General of Canada upon the recommendation of the prime minister and so, to some extent, are representatives of the federal government. In the nineteenth and first half of the last century, they were important conduits between the Dominion and provincial governments, but their role as federal agents is much diminished today. Still, the lieutenant-governor is important in representing the monarch and our Head of State, in having the authority to summon or prorogue the provincial legislative assembly, sign orders-in-council, assent to government bills, and to summon and on rare occasion dismiss provincial premiers. Thus, the lieutenant-governor undertakes several roles involving viceregal and constitutional duties, as well as celebratory and promotional duties. The salary of the lieutenant-governor is paid by the federal government, along with expenses for travel and hospitality. The maintenance of the official residence, Government House, is paid by the provincial government.

The Office of the Lieutenant Governor is perhaps best known to the public for its pageantry. But it has an important constitutional function. It was created under the British North America Act, which established the Dominion of Canada in 1867. Under this legislation (now known as the Constitution Act, 1867), each province is provided with a viceregal official who represents the Crown. These officials are formally appointed by the Governor General of Canada upon the recommendation of the prime minister and so, to some extent, are representatives of the federal government. In the nineteenth and first half of the last century, they were important conduits between the Dominion and provincial governments, but their role as federal agents is much diminished today. Still, the lieutenant-governor is important in representing the monarch and our Head of State, in having the authority to summon or prorogue the provincial legislative assembly, sign orders-in-council, assent to government bills, and to summon and on rare occasion dismiss provincial premiers. Thus, the lieutenant-governor undertakes several roles involving viceregal and constitutional duties, as well as celebratory and promotional duties. The salary of the lieutenant-governor is paid by the federal government, along with expenses for travel and hospitality. The maintenance of the official residence, Government House, is paid by the provincial government.

British Columbia’s viceregal representatives have been the subject of several books. The latest, by Jenny Clayton, is unquestionably the best. The Lieutenant Governors of British Columbia is engaging and informative. Accessible to the general reader, it will impress scholars with its analysis of historical events and breadth and depth of its research. The book offers skillfully-drawn biographical portraits and deft assessments of BC’s chief executive officers from 1871 to 2018. It also provides a sweeping history of the province, since the tenure of each appointee is considered within a wider historical context.

A couple of earlier publications pointed the way for this study and are duly referenced. The first appeared in 1967 and was written by a veteran journalist, D.A. McGregor. A slim volume of seventy-five pages, it was entitled They Gave Royal Assent: The Lieutenant-Governors of British Columbia. It was published as a Canadian centennial project and was apparently the first work of its kind in Canada.[1] A more substantial study was written in 1971 by Dr. Sidney W. Jackman, a professor of History at the University of Victoria. It was undertaken to celebrate BC’s entry into Confederation. Professor Jackman emphasized that his book was not intended to be a “definite collection of biographical essays on the Lieutenant-Governors of British Columbia but rather a series of portrait sketches. It is not a formal historical study — the obvious trappings of scholarship such as footnotes and bibliography are deliberately omitted.” His book was entitled The Men at Cary Castle.[2]

The title derives from an archaic local name given to the official residence of the lieutenant-governor on Rockland Avenue in Victoria, BC. Originally the home of a colonial official, George Hunter Cary, the 1865 structure served as the official residence of provincial lieutenant-governors during the nineteenth century. The official residence is now called Government House. And while there is much to commend in Professor Jackman’s book, its title is quaint. Since his book was published in 1972 three women have served as lieutenant-governors of BC: Iona Campagnolo, Judith Guichon, and the current incumbent, The Honourable Janet Austin, who wrote the foreword to this book.

Clayton’s book does not mark any particular anniversary. It was conceived a few years ago when James Hammond was the Private Secretary at Government House. In 2012, he and Jerymy Brownridge, who was then Director of Operations and is Hammond’s successor, “initiated a number of projects to raise awareness of the Lieutenant Governor’s roles.” These included interpretative signs on the grounds of Government House. Jenny Clayton, who teaches History at Camosun College and the University of Victoria, provided historical images and text for the signs.

Hammond then suggested that a new study was warranted, one that would explore “how the role of the Lieutenant Governor has evolved into the twenty-first century.” Dr. Clayton was commissioned to research and write it. As she remarks in the Introduction, this was an opportunity to reconsider and reposition some significant historical figures. “In my years of researching and teaching the history of British Columbia, I had noted that although Lieutenant Governors showed up almost everywhere, their constitutional and ceremonial actions were rarely central to the story. This book would be a chance to shine a spotlight on their life stories and explore how they had interpreted the role to which they were appointed” (pp. 4-5). She has succeeded admirably in her purpose.

The book’s opening section provides a brief description on the evolving role of BC’s lieutenant-governors. Next, Clayton discusses the colonial governors of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. This chapter is not strictly necessary, but is a bonus. It is intended to set the stage “for the transition [from colonial status] to provincial status and responsible government” and to demonstrate that colonial governors “had much more authority and responsibilities than the Lieutenant Governors who would follow them” (p. 28).

Thirty people have served as viceregal representatives since 1871 and Clayton has chronicled twenty-nine of them. As we learn, each of them was unique and they dealt with their duties in different ways. While she has presented the office-holders chronologically, according to the years when they were appointed, Clayton has provided unifying themes for their terms of office.

In chapter three, she looks at the men who held office from the time BC joined Confederation up to the First World War. The cadre commenced with Joseph Trutch (1871-1876) and concluded with Thomas Wilson Paterson (1909-1914). They “were not only representatives of the Crown, but also agents of the federal government…. All had spent part of their careers in the capital [Victoria, BC] working for the federal government or had served as federal government agents elsewhere” (p. 29).

Clayton discusses BC’s response to the First World War in chapter four and describes how the war affected Government House. “As representatives of the Crown, the Lieutenant Governors and their chatelaines … served as role models in their support of the armed forces and war-related fundraising efforts. After the war, they helped to usher in a new peace, representing the Crown in commemorative events in an attempt to come to terms with the incomprehensible losses” (p. 100). Francis Stillman Barnard (1914-1919) and Edward Gawlor Prior (1919-1920) were incumbents during this period. Both had served as Members of Parliament before their appointment as viceregal representatives. “Prior was the last of a series of politically experienced ‘Ottawa’s men’ to serve this role,” Clayton says. “After Prior, the role of the Lieutenant Governors of British Columbia would undergo a dramatic shift” (p. 114).

The political experience of men appointed before 1920 was crucial in carrying out the constitutional duties of the lieutenant-governor. British Columbia was noted for its political instability in the late nineteenth century: recall the hurly-burly turnover of governments led by Theodore Davie, John Turner, Charles Semlin, and “Fighting” Joe Martin. And even with the advent of party-based politics after 1903, there were uncertainties. During his term, Barnard accepted the resignation of one premier (Richard McBride) and administered oaths of office to three others — William Bowser, Harlan Brewster and John Oliver. Provincial politics were relatively stable afterwards and, Clayton says, from 1920 to 1960 “political and legal experience were not essential for the job, while a willingness to travel, promote British Columbia and host large events became increasingly important” (p. 116).

Walter Cameron Nichol (1920-1926) was the first viceregal representative of the new order and is introduced in chapter five. Soon after his appointment he visited communities in the Okanagan and Kootenay regions of BC and in 1924 travelled to Yuquot (Friendly Cove) on the west coast of Vancouver Island. He was accompanied on that occasion by a prominent BC historian, Judge F.W. Howay. They were there to unveil a cairn erected by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. Clayton includes a photo of Nichol meeting a Nuu-chah-nulth chief wearing traditional regalia. The chief, Clayton notes, “took the opportunity of an audience with the Crown’s representative to argue that the anti-potlatch law of 1884 should be withdrawn” (p. 121).

She discusses the Office of the Lieutenant Governor during the 1930s in a chapter entitled “Retrenchment and Extravagance.” John William Fordham Johnson (1931-1936), formerly president of the confectionery conglomerate BC Sugar, served during the darkest years of the Depression and was mindful that his post was viewed by some taxpayers as an unnecessary expense. In Alberta and Ontario, the official residences of lieutenant-governors were closed as a cost-cutting measure. The abode on Rockland Avenue in Victoria was spared but maintenance payments from the provincial government were reduced. However, Johnson’s successor, timber baron Eric Werge Hamber (1936-1941) was independently wealthy and not inconvenienced by retrenchment. He and his wife Aldyen spent $50,000 “of their own money on entertainment and other expenses while he held the post” of lieutenant-governor (p. 144).

As Clayton observes, some potential candidates declined to be considered because they could not afford the financial burden or were not prepared to cover the costs from their own pockets. Consequently, a practice of appointing wealthy men to Government House was established. These men included William Culham Woodward (1941-1946), a department store magnate and cattleman, and Frank Mackenzie Ross (1955-1960), a former banker, business manager and another cattleman. (Ross was co-owner of the Douglas Lake Cattle Company which operated the largest cattle ranch in the Commonwealth). When Government House was destroyed by fire in April 1957, Ross and his very accomplished wife, Phyllis Turner Ross, “played a significant role in the furnishing” of a new building – the handsome structure that stands today. They provided the house with new furniture and décor and commissioned a new set of portraits of former lieutenant-governors to replace ones lost in the fire (pp. 179-180).

Incidentally, this was the second time the official residence had been destroyed by fire. The first occurred in 1899 when Thomas Robert McInnes (1897-1900) was lieutenant-governor. That conflagration destroyed the original Cary Castle. A new residence, designed by Samuel Maclure and Francis Rattenbury, was completed in 1903. In designing its replacement after the 1957 fire, architects with the provincial Department of Public Works used the Maclure-Rattenbury plans as guidelines.

An era of wealthy entrepreneurs in Government House drew to a close when Ross retired. His successor, George Randolph Pearkes (1960-1968), was a gallant soldier who earned the Victoria Cross in World War I. In the Second World War, Pearkes was the General Officer Commanding in BC. After the war, he sat in Parliament as Conservative MP for Nanaimo and served as Minister of Defence in John Diefenbaker’s government. Pearkes was extremely popular and Prime Minister Lester Pearson asked him to extend his term of office in order to help celebrate Canada’s centennial.

Robert Gordon Rogers (1983-1988), a tank commander in the war, culminated his corporate career as president of a major forestry company, Crown Zellerbach. In 1988, he and his wife Jane established the Government House Foundation, “which to this day raises funds to preserve and enhance Government House.” Its first project was to commission and install a magnificent stained-glass window above the main staircase. Subsequently “it became customary for Lieutenant Governors to design personal legacy projects assisted by the Government House Foundation” (p. 236).

In the penultimate chapter, the author underscores the “Diverse Identities” of the modern Office of the Lieutenant Governor in BC. She discusses the tenure of David See Chai Lam (1988-1995), the first Chinese Canadian to hold office. For his legacy project, Lam created a new rose garden at Government House and provided equipment for a volunteer horticultural group (p. 247). The group is now called the Friends of Government House Gardens Society and boasts more than four hundred members.

Iona Victoria Campagnola (2001-2007), the first woman to hold office, established two awards: The Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Excellence in BC Wines and Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Literary Excellence. She designed a new uniform for herself that featured Indigenous motifs including a killer whale and eagle. A striking portrait of her wearing the uniform graces the cover of this book.

Regarding Steven Lewis Point (2007-2012), Clayton writes: “The appointment of an Indigenous Lieutenant Governor had long been overdue, but when it came, it signalled a commitment to reconciliation” (p. 282). His legacy projects included programs to provide books to isolated First Nations communities and promote youth development through Aboriginal cadet corps. His legacy can also be seen in a bandshell and totem pole on the grounds of Government House. [Point’s Indigenous name is rendered in an orthographic script as Xwĕ lī qwĕl tĕl but the pronunciation of his name in English is not offered in this book.]

In a very brief concluding chapter, Clayton remarks that while “earlier appointees were focussed on advancing the interests of settler society, modern representatives of the Crown have made it a priority to recognize Indigenous culture and history, emphasizing respect and reconciliation” (p. 297).

Clayton provides biographical sketches of BC’s viceregal representatives, plus information about their spouses and other family members, over a period of nearly one hundred and fifty years. The term “sketches” does not do justice to the work that is presented here: “essays” is a better term. Clayton devotes about six or seven pages, or approximately three thousand words, to each subject.

Some of the essays are shorter, notably those on Albert Norton Richards (1876-1881), Thomas McInnes, Fordham Johnson, and Charles Arthur Banks (1946-1950). Several essays, including those on Lam, Pearkes, and Point, are longer. The longest entry in the book is devoted to Judith Guichon (2012-2018). A rancher and environmentalist, Guichon did not anticipate having to make a momentous decision about choosing a premier when she was appointed. In 2017, in the aftermath of a very close general election, Guichon had to weigh competing claims from the incumbent premier, Christy Clark, and the leader of the Opposition, John Horgan. After studying precedents and considering legal advice from constitutional lawyers and other viceregal representatives, she “chose to exercise her reserve powers” and invited Horgan to form a minority government (p. 295).

As the publisher’s blurb says, this book is “rich with photographs.” The book is illustrated with nearly seventy photographs and remarkably the majority of them (nearly fifty) are published courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives. That’s remarkable because most authors and publishers cannot afford to pay the archives’ licensing and reprographic fees. Authors and publishers who are producing books today about BC seek out other sources – such as the exemplary and obliging City of Vancouver Archives – for images to illustrate their publications. Did the Royal BC Museum and Archives discount or waive its reprographic fees for this book, or did the Government House Foundation underwrite this publication expense?

Clayton’s book raises more important questions. When did the federal government begin consulting with provincial premiers about suitable candidates as viceregal representatives? Clayton mentions that Premier Byron Johnson may have been behind the recommendation of Clarence Wallace (1950-1955) as a potential lieutenant-governor (p. 170). But did such recommendations occur previously? And when did the lieutenant-governor cease to be an agent and confidante of the federal government? Ostensibly, that role stopped in the early decades of the last century, but maybe it did not. In 1973, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau may have selected Walter Owen (1973-1978) — described as “an anti-communist lawyer” who “earned a reputation for advising companies on how to challenge unionization” – as a “counterbalance” to the newly-elected socialist NDP government of Premier Dave Barrett (pp. 210, 215).

What about viceregal and executive council relations? Sir Henri Joly de Lotbinière (1900-1906) once described his role as being “an advisor to my advisors” (p. 83). How did the lieutenant-governors get along with their advisors? Or, to put the question another way, how did provincial premiers get along with the viceregal representatives with whom they were required to consult on myriad issues? It is interesting to speculate how populist premiers such as T. D. Pattullo and W. A. C. Bennett regarded their advisors — Hamber and Woodward; Wallace, Ross, Pearkes and John Robert Nicholson (1968-1973) respectively.

Unlike Professor Jackman, Clayton has provided the “trappings of scholarship such as footnotes and bibliography.” The Select Bibliography lists over one hundred and sixty books and articles, and refers to interviews that Clayton conducted with Guichon, Point, and Campagnola, former private secretaries and others. She has read manuscripts, including Richard Mackie’s unpublished biography of Eric Hamber (1987), which is kept with the Hamber family papers (AM1036) at the City of Vancouver Archives. She has consulted material at Government House and acknowledges a “volunteer Archives Group” that gave her “useful advice and assistance with sources” (p. 313). [The archives at Government House is not open to the public but may be more accessible in the future.]

Clayton refers to a few sources in the BC Archives, including a scrapbook of newspaper clippings (MS-1320) compiled during the tenure of Walter Nichol and a collection of government records pertaining to the reconstruction of Government House after the fire of 1957 (GR-1962. British Columbia. Provincial Secretary, 1957-1963). Surprisingly, at least to this reviewer, she does not mention an extensive collection of official records accessioned in the BC Archives as GR-0443 (British Columbia. Lieutenant-Governor, 1871-1936). She may have consulted this fonds during the course of her research but does not refer to it in the Endnotes or Select Bibliography.

GR-0443 consists of communications between the lieutenant-governors of BC and the Governors General of Canada, and between BC’s viceregal representatives and the Secretaries of State for Canada. Correspondence with provincial government ministers and despatches from Senior Officers of the Royal Navy station in Esquimalt are also preserved in this fonds.

Clayton’s book is not diminished because GR-0443 is omitted in the list of sources. The archival government records are mentioned here for the benefit of future researchers who may be interested in examining aspects of the viceregal office during the last quarter of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth century. Those researchers will be grateful to Clayton for providing a good foundation for them to build on.

Readers will enjoy the anecdotes and stories that Clayton has woven into her narrative. For example, we learn that McInnes – who is remembered by some historians and political scientists because of a constitutional imbroglio known as the McInnes Incident – presided at the opening of the new Parliament Buildings in February 1898. He used a golden key to unlock the front door (p. 72). In May 1899 his residence, Cary Castle, was consumed by fire. With the exception of his uniform, “which was thrown out when the alarm was first given,” McInnes and his family “lost all of their personal effects, including clothing, jewels and private papers” (p. 73). Fortunately for historians, the official papers of the lieutenant-governor had been transferred to the newly-established Provincial Archives just before the conflagration. By the way, the uniforms worn by McInnes and Campagnola are preserved in the Royal BC Museum.

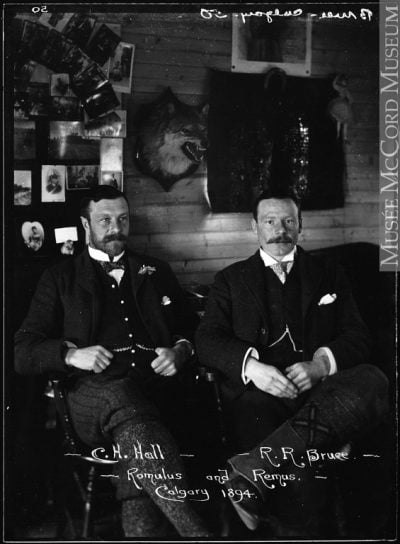

In January 1912, in Oak Bay, Thomas Paterson dropped the puck at an artificial ice hockey rink in “the first professional hockey game played west of Toronto” (p. 97). In May 1915, dozens of soldiers stood guard at Government House following anti-German riots in Victoria. Lieutenant-Governor Barnard’s wife, born in Victoria of German descent, was threatened. Robert Randolph Bruce (1926-1931), a widower, relied on his young niece, Helen Mackenzie, as the hostess at Government House functions. She also acted as his amanuensis and “as his eyes,” since he was legally blind. “He preferred not to reveal this disability to the general public, so she read official papers and speeches to him, allowing him to memorize them, and at gatherings she would cue him in advance, enabling him to “recognize” guests” (p. 127). These are but a few morsels from the anecdotal smorgasbord in this book.

All in all, this is an impressive work. Jenny Clayton has provided a comprehensive account of the lieutenant-governors of British Columbia and a summary of key events and issues in the social and political history of the province. The Government House administrators who commissioned this book and the author who researched and wrote it deserve high praise. The Lieutenant Governors of British Columbia deserves a wide readership.

*

Patrick Dunae was born in Victoria and lives there now. He taught BC history at the University of Victoria and Vancouver Island University. Previously, he was an archivist in the Manuscripts and Government Records Division of the Provincial Archives. One summer, when he was an undergraduate, he worked as a labourer on the grounds of Government House.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] D.A. McGregor, They Gave Royal Assent: The Lieutenant-Governors of British Columbia (Vancouver: Mitchell Press Limited, 1967).

[2] S.W. Jackman, The Men at Cary Castle (Victoria: Morriss Printing Company, 1972).

2 comments on “#657 Government House calling”

Comments are closed.