#645 The journeys of Eizo Osada

The Return of the Shadow

by Kunio Yamagishi

London: Austin Macauley, 2018

£6.16 (U.K) $25.95 (Cdn) / 9781786937155 / Please order from your local bookstore or through Book Depository who offer free worldwide shipping.

Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

*

In July 2019, The Return of the Shadow, by Comox Valley writer Kunio Yamagishi, was shortlisted for a 2019 Rubery Book Award (Birmingham, UK) in the Fiction category – Ed.

*

In 1977, while working at the Japanese Consulate General’s office in Toronto, Kunio Yamagishi became aware of Eizo Osada. Although Yamagishi did not deal with him directly, he noticed how Osada seemed “haunted by a nightmare” and a “guilty conscience.” The image was etched in Yamagishi’s “head like a shadowgraph” (p. 11). Osada wanted to renew his passport in order to return to Japan where 43 years earlier he left a wife and three young sons. The consulate could not oblige since he could not provide his family’s registration paperwork — a clue to the plot of the story. Moreover, because he had taken out Canadian citizenship, Japan no longer considered him one of theirs, so he returned to Japan on a Canadian passport.

In 1977, while working at the Japanese Consulate General’s office in Toronto, Kunio Yamagishi became aware of Eizo Osada. Although Yamagishi did not deal with him directly, he noticed how Osada seemed “haunted by a nightmare” and a “guilty conscience.” The image was etched in Yamagishi’s “head like a shadowgraph” (p. 11). Osada wanted to renew his passport in order to return to Japan where 43 years earlier he left a wife and three young sons. The consulate could not oblige since he could not provide his family’s registration paperwork — a clue to the plot of the story. Moreover, because he had taken out Canadian citizenship, Japan no longer considered him one of theirs, so he returned to Japan on a Canadian passport.

Osada was a real person and Yamagishi interviewed people who knew him in Canada. Yet, while reading like a biography, The Return of a Shadow is a work of fiction and can be read as a mystery novel. Yamagishi draws on published histories to provide background; on interviews to create details of Osada’s life; and on his imagination to add dramatic interest. It is a compelling story of the hardships and discrimination faced by the Japanese in British Columbia and culminating with their removal from the coast in 1942 and the consequences of long-term family separation.

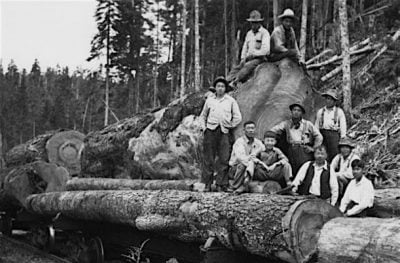

When he arrived in British Columbia in 1935, Osada was one of seventy Japanese who immigrated to Canada that year. With insufficient land in Japan to support his family, he followed a friend who claimed to be making good wages as a logger near Cumberland. Like his friend, he planned to earn money to send to his family and ultimately rejoin them in Japan. His Japanese “boss” exploited him and other workers so when the opportunity arose, he moved to a sawmill in Campbell River. Conditions were no better; he returned to the logging camp.

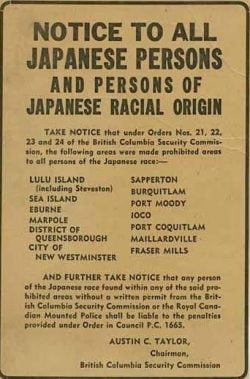

Osada’s story is a composite of Japanese Canadian experiences. Conveniently, he was at key places at critical times. On 7 December 1941, the day that Canada declared war on Japan, Osada was in Vancouver. Seeking news, he was visiting the offices of Tairiku Nippo, a Japanese language newspaper, when the RCMP advised the editor to cease publication. Osada returned to Vancouver Island the next day; five days later, his Japanese boss lost the labour contract and he was unemployed.

A Japanese friend provided accommodation in Cumberland where he stayed until mid-April when, along with his host family, he was told to be ready the next day to move to Hastings Park in Vancouver. Shortly thereafter, he was briefly sent to a road camp where Japanese men, with picks and shovels, went through the motions of building the Yellowhead Highway. When workers were needed to build accommodation for Japanese men, women, and children, he was sent to Tashme, a purpose-built camp just outside the coastal defence zone, where he spent the remainder of the war years. Although he had no property, he saw the trauma that the confiscation and sale of their property caused to others. Like them, he shared the dilemma of deciding between going to Japan after the war, or staying in Canada but leaving British Columbia. Concerned for how his family might fare in war-damaged Japan, he opted to stay in Canada and resume sending money. He moved to Ontario. After doing menial jobs for several years, he found work in a soft drink factory where he remained for twenty-two years before retiring at age 70. His kindly hajukin employer appreciated his hard work and assisted Osada, whose knowledge of English was limited, in dealing with governments.

Save for the war years when communication with Japan was impossible, Osada regularly sent money to his family and exchanged letters. In 1954, he informed them of his plan to return. Rather than welcoming this prospect, Kino, his wife, citing unemployment in Japan, urged him to stay in Canada so he could send money. Apart from a few notes from a daughter-in-law he heard no more from his family and had not received any letters for a decade.

Despite the absence of correspondence and uncertainty about his reception, he was determined to return to Japan when he retired. A son, who lived in Tokyo, met him at the airport and gave him lodging and meals for several days but would not let him speak to Kino on the telephone and was evasive about her wellbeing. Not until Eizo visited his eldest son who, with his wife, cared for Kino, did Eizo discover what his sons were hiding. After an affair with a man who then left her, their mother suffered a severe mental breakdown. Her peculiar habits in wandering about the village made her a local laughing stock and severely embarrassed the family who treated Eizo civilly, but coldly.

Yamagishi, a native of Japan and a graduate of Hosei University in Tokyo, knows the Japan to which Osada returned, members of the Nikkei community in Canada, and the lay of the land of Vancouver Island: he now lives in Comox. Through secondary characters, he develops some minor themes such as the “rat race” of Tokyo compared to the relative calm of Toronto and the perceptions that the post-war Japanese immigrants to Canada and their pre-war counterparts had of each other. He also notes how Issei and Nisei, the first and second generation of immigrants, tried to protect their children and grandchildren from knowledge that might “extinguish the light of hope” for their future in Canada, but instead created bitterness among their descendants (p. 313).

Moreover, Yamagishi draws on his knowledge of Japanese culture to explain the thinking of Osada and other Nikkei. He suggests, for example, that most Nikkei resignedly obeyed the order to leave the coast because of their beliefs in okami no meirei, that orders from authority must be obeyed and in the “Buddhist sense of resignation and passivity” (p. 283).

The “shadow” is an effective literary device through which Yamagishi expresses Osada’s thoughts. Italics set off the musings of the shadow — his talking to himself and his conscience. The shadow provided some comfort as an escape from loneliness; when he anticipated a warm welcome from his wife, he wanted it to disappear (p. 163). When his wife rebuffed him, the shadow returned with an overwhelming theme of Eizo’s strong sense of guilt for Kino’s illness, which he attributed to his long absence.

The book does not have a happy ending. It is not quite a mystery novel, but revealing the details would eliminate the suspense that adds to the pleasure of reading it. For all readers, The Return of a Shadow is a well-informed introduction to the experiences of many Japanese in Canada who lived through the war years and to the reception encountered by some who returned to Japan.

*

Patricia E. Roy, a native of British Columbia, is professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria where she taught Canadian history for many years. Her own research has been mainly in the field of British Columbia history and she is best known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989); The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007). All were published by UBC Press. Her longstanding interest in BC’s political history resulted in Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012). Editor’s note: Patricia Roy’s latest book is The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 2018), reviewed here by Chad Reimer.

Patricia E. Roy, a native of British Columbia, is professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria where she taught Canadian history for many years. Her own research has been mainly in the field of British Columbia history and she is best known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989); The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007). All were published by UBC Press. Her longstanding interest in BC’s political history resulted in Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012). Editor’s note: Patricia Roy’s latest book is The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 2018), reviewed here by Chad Reimer.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.