#643 Father, daughter, and Tarot

My Father, Fortune-tellers & Me: A Memoir

by Eufemia Fantetti

Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue Publishing, 2019

$21.95 / 9781896949758

Reviewed by Linda Rogers

*

“Children are resilient,” they say. “What doesn’t kill them makes them stronger” is another variation. It seems that religion, proverbs, and shibboleths were invented to justify the traumatic malformation of child psyches that has led to millennia of war and inter-generational cruelty, the sad trajectory of human history.

“Children are resilient,” they say. “What doesn’t kill them makes them stronger” is another variation. It seems that religion, proverbs, and shibboleths were invented to justify the traumatic malformation of child psyches that has led to millennia of war and inter-generational cruelty, the sad trajectory of human history.

In My Father, Fortune-tellers & Me, truth is always stranger than fiction-writer Eufemia Fantetti’s affirmation of the dis-empowering myth that started in the Book of Isaiah, “When the (mother) eats sour grapes the (daughter’s) teeth are set on edge.” Gender is fluid these days. The proverb comes from an ancient patriarchy, but girls are equal opportunity victims. Her book is testament, a memoir of twisted matriarchy, the congenital disease of suffering and endurance.

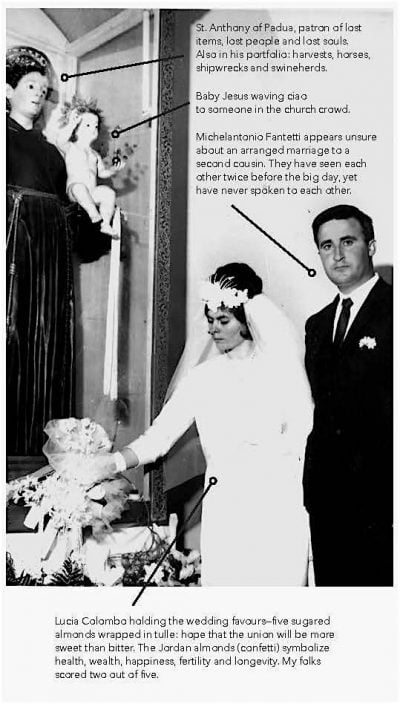

Just as livestock is cursed by inbreeding, so is the author’s disturbed paesan bloodline. Fantetti’s genetic memory is of Southern Italian mountains blocking the light, generational deprivation of sanity replaced by superstition and dangerous crevasses.

The assumption that children thrive in terra firma and struggle with peaks and valleys, the impassable cracks in intransigent land formations, has yet to disarm the dangerous demographic that torments forming minds. And so, generation after generation, young people distorted by trauma grow up to beget.

The Fantetti family chose to emigrate from the mountainous Molise region of Southern Italy, but flight only exacerbated their dysfunction, as it so often does with immigrant families beset with traumatic memory and thwarted dreams. After years of abused husband and child clinging desperately to one another, Fantetti’s mother is diagnosed with schizophrenia. That is only one part of Eufemia’s terrible legacy, not the least of which is a father broken by the sacrament of marriage, family, and social dysfunction, with church and state conspiring to control the bodies and minds of a population costumed in a hybrid mess of superstition.

The author succumbs to anxiety, the ultimate tool of hyper vigilant artists, but her father is broken spiritually and physically by the effort to effect normality, whatever that is in a society shaped by fear and apprehension.

Fantetti is the dysfunctional parent’s worst nightmare, a child with the gift of tongues. And she tells, although no one at first seems to listen. With the stubbornness of her ancestors, resolute survivors of every disaster from war to famine, she would reach out to a new audience, sympathetic readers with a higher empathy quotient than the non-listeners in family, church, school, and the medical professions. When she had previously pleaded for her own survival and that of her abused father, no one truly heard:

I thought please, please, please, please, please, please, please, please, please, please, God, you deaf bastard. Don’t take my father. He’s all I have.

Even, Goddess help him or her, because poetry is the most intimate of writing exercises, her poetry prof at UVic failed to unlock her metaphors and gave this eventual award winning writer a failing grade.

Buon fortunata, Fantetti eventually found her platform in comedy, the stage of the truly unhappy, and in theatre, fiction, and memoir; so we are enlightened.

The range of normal finds its extremes in intransigent peasant communities like the Molise/Abruzzo region, which is so under populated that the Italian government offers stipends to settlers. Bound by Catholic ideology and a stubborn almanac interrupted by earthquake and insanity, it is the cultural equivalent of suffocation, specializing in sensory deprivation in spite of its beauty, the reason why so many have left.

Although the author grew up half a world away from the intimidating peaks and valleys of this region, she was subjected, like many first and second-generation immigrants, to a double down in its invisible forces. This is a common story, hers exacerbated by inter-generational maternal psychosis.

This book is a part personal memoir, her own map, and part map to the migration patterns of humans, a social requirement in these shifting geopolitical times. Fantetti writes with the acuity of the emotionally alert. She has intimate knowledge of physical and emotional dislocation and extraordinary descriptive skills.

She stages the psychotic episodes in amazing sensory detail, conveying the smell of madness and fear, and describes her anxious victim world, the horrible timbre of suffocation, with frantic immediacy. It is impossible to escape the effect of her explication of living death, and inhuman not to wish for the resolution that might come at the end of a long series of agonizing epiphanies:

I felt like a diver being lowered into the depth of the sea in a shark-proof cage, realizing at the last moment that I was not properly equipped.

They say reading develops empathy. If this book isn’t a primer on the sensitivity of children to the positive and negative effects of adult behaviour, then there is no book of change to inform the universal caretakers of bombed and caged infants and no affirmation for those who manage, with and without help, to transcend negative patterning and become the book of what is to come.

Through her father, Fantetti discovered another world of destiny, another mythology to explain the patterns of predestination and self-determination, the Tarot, and she has used the cards to explicate a life that too often felt un-navigated. Each chapter is named after a card from the major arcana. Tarot is Fantetti’s comfort and also the structure of this memoir, explaining destiny and free will in unconditional terms. From The Fool to The World, she is succeeding. Redemption is being free to speak and being heard. It is being. Free at last.

*

Linda Rogers’ recent book is Yo! Wiksas? Hi! How are you? (Exile Editions: 2019) with artist Chief Rande Cook, and she is about to move on Repairing the Hive, third book in the Empress trilogy, and the collaborative Arioso Game with Ben Murray, shortlisted for the BC Great Novel Search. She is also working with fellow writers and artists on Mother, the Verb.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#643 Father, daughter, and Tarot”

Comments are closed.