#592 Ginger beef and fried macaroni

Chop Suey Nation: The Legion Cafe and Other Stories from Canada’s Chinese Restaurants

by Ann Hui

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2019

$24.95 / 9781771622226

Reviewed by Imogene Lim

*

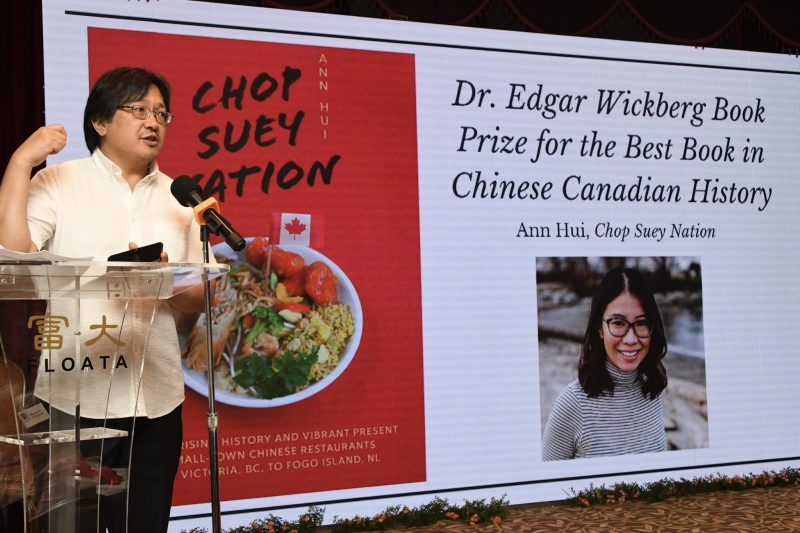

In March 2019, B.C. Bestseller Chop Suey Nation, by Ann Hui, was awarded the 2019 Dr. Edgar Wickberg Book Prize by the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of B.C. for the Best Book on Chinese Canadian History. In June 2019, Chop Suey Nation was longlisted for the Toronto Book Awards.

Ormsby reviewer Dr. Imogene Lim identifies Chop Suey restaurants in Canada — from Fisgard Street in Victoria to Fogo Island, Newfoundland — as springboards for immigrant Chinese families to establish themselves as Canadians, put their children through university, and sometimes achieve professional status for their offspring — Ed.

*

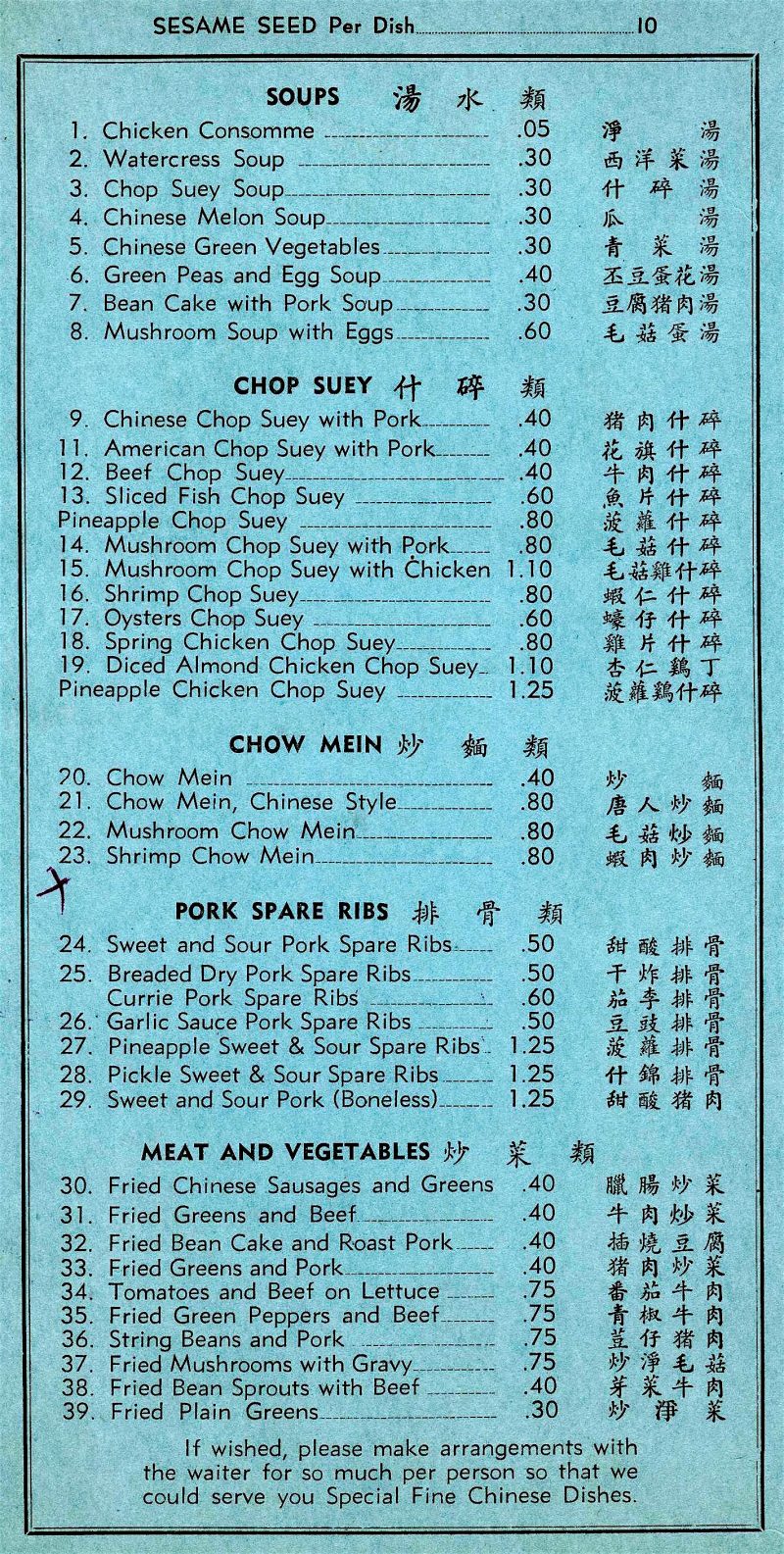

The words “chop suey” serves as a shorthand, a signifier, to announce to diners throughout Canada and the United States that the restaurant is a Chinese one that also offers a specific kind of Chinese cuisine, a westernized version (Lim 2005: 13). It was a means of introducing foods, foreign to most of its non-Chinese clientele, that has evolved over the decades. “Chop suey” today is less likely to be served in urban centres where there is a sizeable population of individuals of Asian ancestry. However, Chinese cafés and restaurants of the chop suey variety continue to dot the landscape of small-town Canada.

The words “chop suey” serves as a shorthand, a signifier, to announce to diners throughout Canada and the United States that the restaurant is a Chinese one that also offers a specific kind of Chinese cuisine, a westernized version (Lim 2005: 13). It was a means of introducing foods, foreign to most of its non-Chinese clientele, that has evolved over the decades. “Chop suey” today is less likely to be served in urban centres where there is a sizeable population of individuals of Asian ancestry. However, Chinese cafés and restaurants of the chop suey variety continue to dot the landscape of small-town Canada.

Ann Hui, the Globe and Mail National Food Reporter, takes readers on a road trip from coast to coast in Chop Suey Nation: The Legion Cafe and Other Stories from Canada’s Chinese Restaurants. The number of places visited are limited given her travel time of 18-days, beginning in Victoria, with Fogo Island, Newfoundland, as the final destination. Nevertheless, her thoughtful interviewing of owners brings to light the circumstances that continue to bring Chinese immigrants to seek opportunities where they can, just as earlier ones did, whether in the early 1900s, the 1950s, or the 2000s.

Hui’s book expands upon her original two-part article published in the Globe and Mail as “Chop Suey Nation: A road trip uncovers the lives behind small town Chinese Canadian food” (2016). In the book, Hui ably intertwines three stories: early Chinese Canadian immigrants, experiences of the restaurateurs she met, and her own family’s history as immigrants and owners of Chinese restaurants. This distinguishes it from other books about Chinese food in the North American context, especially academic ones which focus on cultural history (Coe 2009) or on diasporic culture and restaurants (Cho 2010).

Hui is a storyteller at heart and a very good one at that. She makes history readily accessible by introducing details as snippets to link one part of her story to the next. For example, her rationale for beginning her journey in Victoria: “it seemed logical to begin the trip on the opposite coast, in British Columbia. After all, B.C. was where the first major wave of Chinese men arrived in Canada in search of gold” (p. 22). Or in explaining Chinese immigrants opening restaurants and social policies: “Many had only started restaurants because they had no other options, because the work didn’t require formal training or much English, and also because until the mid-twentieth century, they had been barred from other professional occupations” (p. 77).

Hui explicitly delineates waves of immigration marked by regions as well as by social class and the impact of their arrival, including on the restaurant/food scene. Chinese immigrants to Canada are not monolithic, they are an expression of diversity and heterogeneity. As she notes, “The 1980s and 1990s introduced Canada to a new kind of Chinese. […] there were hundreds of thousands of middle class and wealthy Hong Kongers” (p. 46). Then, among the most recent, “the new newcomers are a diverse set, including middle class and poor Chinese too. […] [who] brought with them to Canada great, authentic and diverse regional Chinese cuisines” (p. 48).

In her overall story, she frames her own family’s experience within the larger context of immigration patterns in Canada and beyond. For example, while her grandfather (Ye Ye) was a child, there was an absence of his father (Ah Gong): “Gum San. Gold Mountain. […] [They] were so poor that the villages could only feed their sons by sending them away. […] Gum San wasn’t just one place. It could be Canada, or the United States, or Australia, or Holland. It just meant ‘away.’” (p. 66). Part of the story is how one arrives, especially in the first half of the 20th century. “Great Aunt’s offer to Ye Ye had come with one major condition. He’d had to give up his own identity. ‘He was a paper son’” (p. 247). As explained by Hui, “citizenship documents for husbands and sons and nephews were bought and sold to those desperate enough to pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars for these” (p. 248; see also Chan 2017).

Hui’s focus on small-town Chinese restaurants is one that has been explored by others as a topic of their identity as Canadians. The number of associations with the Prairies is striking, with one of the first documentaries on the topic produced in 1985 by Anthony Chan, Chinese Cafés in Rural Saskatchewan. Michelle Wong also explores her roots as a family of intergenerational Chinese café operators (Boston Cafe) in St. Paul, Alberta, in Return Home (1992). Almost two decades later, the Royal Alberta Museum hosted a travelling exhibit “Chop Suey on the Prairies” (Wheeler 2012).

Identity for Hui while growing up is also associated with food. How can you invite school friends home for a meal without being embarrassed? “The food we ate at home was something different. It was the same kind of different I felt when the white girls in class had sleepover parties” (p. 14). As noted by a school aged Hui, this was not “normal food,” as “sold at Safeway and advertised in cartoon commercials” (p. 14).

With family focused on surviving in the restaurant business, Hui with the benefit of hindsight and her conversations with the many restaurateurs, who she met, comes to understand the sacrifices made for the next generation’s success as Canadians. The Kwang Tung Restaurant of Fogo Island is a perfect example. The Huang family, by coming to Canada was “invest[ing] in themselves, to take advantage of new opportunities” (p. 231). In their case, owning two restaurants meant separation. “Like the families of the Gold Mountain men, the Huangs would live apart. Only instead of being split across continents, the Huangs were split by the harbour” (p. 232).

A lot of hard work is involved, as well as timing and/or luck. Although Hui focuses on successes, she is well aware of the reality of running a business. “For every family that found Gold Mountain, there were many others who didn’t. […] many faded restaurants I had visited seemed on the verge of shutting down. […] towns where one after another, the storefronts were shuttered” (p. 280).

Recent arrivals come from different social backgrounds. Without the Huangs’ back story, a reader of headlines, such as, “Montreal real estate: Wealthy Chinese increasingly investing in properties overseas” (Tomkinson 2018), might assume that in purchasing a house in an Oshawa development (p. 261) that they were among the nouveau riche of China. In reality, the Huangs lived separately and worked “365 days a year and never close[d] their restaurants [and] […] never, ever spent any money on themselves” (p. 258). In purchasing a house, the Huangs had “[t]he picture-perfect retirement they’d always dreamed of” (p. 261).

The Huang story, as well as Hui’s, is a reminder that behind the multiple accounts of immigration and restaurants is a love story to family. “It wasn’t what they came for, but who” (p. 241). When readers see headlines about migrants endangering their lives to reach Europe, the United States, or Canada, especially when travelling with children, we need to remember the conditions that propel them to undertake such a journey. As already noted, Hui’s grandfather was a “paper son,” not a “legal” means of immigration. He left China because of and for his family. When immigrants arrive, they give up familiarity and home to build something new.

Depending on when they arrived, their welcome varied. During the first wave of Chinese immigration to Canada, anti-immigrant sentiment rose, leading to numerous pieces of legislation directed at the Chinese. Based on economic and social fear, that same opinion is being heard today of peoples arriving from South and Central America, from Africa, from the Middle East. “40 per cent of Canadians believe that an influx of immigrants could make it more difficult for Canadian citizens to get jobs. Despite this, much of Canadian immigration deals precisely with the labour shortages that the home-grown workforce isn’t able to fill” (Volmiero & Russell 2019). The immigrant origins of the many who call themselves Canadian, by birth or naturalization, should not be forgotten.

“Modern” Canada is an immigrant nation. Beyond feeding communities, the children of these restaurant families have made their mark on the larger Canadian society. They have established themselves as Canadians. Hui is a reporter for one of Canada’s national newspapers. The Huangs’ daughter, Stacy, is a physiotherapist (p. 258). William Choy of Stony Plain, Alberta, became mayor (p. 91). And I, your reviewer, also the child of a Chinatown restaurateur, am an educator. Anthony Chan, already mentioned for his Chinese Cafés in Rural Saskatchewan, chronicled his own Victoria family and their last restaurant, The Panama (1996). He, too, was a scholar and educator (CFMDC 2019).

Chinese immigrants and their cafés and restaurants, like McDonald’s tag line, have served millions and millions, without considering their impact on the local economy. As one “chop suey” restaurateur in the United States said, “that’s our business. It put a lot of kids through college so they can find better jobs now, get themselves a better education” (Mizes-Tan 2019). If not for immigration, the resilience and entrepreneurship of those earliest Chinese pioneers, what would the food landscape of Canada be? Think of the regional specialties offered across Canada: Alberta ginger beef (p. 76), Thunder Bay bon bons (p. 123), Québec fried macaroni (p. vi, 196), and Newfoundland chow mein (p. 197). These are dishes “made in Canada” as are the descendants of those “chop suey” restaurant pioneers.

*

A descendant of Cumberland and Vancouver’s Chinatowns, Dr. Imogene Lim is an anthropologist (BA Hons, Simon Fraser University; AM & PhD, Brown University) at Vancouver Island University, where she teaches Anthropology and in the Global Studies Program. As a field language, she learned to speak Swahili. For the past two decades she has focused her research interests on Vancouver Island — ethnicity in Canada and Asian Canadian history. In this regard, she has served on the BC Legacy Initiatives Advisory Council (in response to the Chinese Historical Wrongs Consultation Final Report), the BC Chinese Canadian Community Advisory Committee, Working Group-BC Chinese Canadian Museum, and the Coal Creek Historic Park Advisory Committee (Cumberland). She is a founding member and former Board Director of the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of BC.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

References:

CFMDC, “Dr. Anthony Chan,” 2019: https://www.cfmdc.org/filmmaker/1054

Anthony Chan, director, The Panama (Seattle, Sun Riders Production, 1996): https://www.cfmdc.org/film/954 [copyright date incorrect on this ref, which has 1997, see film credits on https://youtu.be/ZNu3Ol_FYM4]

Anthony Chan, director, Chinese Cafés in Rural Saskatchewan (Seattle, City Production, 1985): https://www.cfmdc.org/film/247

Arlene Chan, “Chinese Immigration Act,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 7, 2017: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act

Lily Cho, Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu in Small Town Canada (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2010).

Andrew Coe, Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (New York, Oxford University Press, 2009)

Ann Hui, “Chop Suey Nation: A road trip uncovers the lives behind small town Chinese Canadian food.” The Globe and Mail, June 21, 2016: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/food-and-wine/chop-suey-nation/article30539419/

Imogene L. Lim, “Mostly Mississippi: Chinese Cuisine Made in America,” Mostly Mississippi: Chinese Restaurants of the South, by Indigo Som, Exhibition Catalog, pp. 13-15. (San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America, 2005): http://wordpress.viu.ca/limi/files/2012/07/MostlyMississippiEssayLim.pdf

Sarah Mizes-Tan, “How the Chow Mein Sandwich Claimed a Small Slice of New England History,” The Salt, NPR, June 24, 2019: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/06/24/732028721/how-the-chow-mein-sandwich-claimed-a-small-slice-of-new-england-history

Briana Tomkinson, “Montreal real estate: Wealthy Chinese increasingly investing in properties overseas,” Montreal Gazette, September 7, 2018: https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/montreal-real-estate-wealthy-chinese-increasingly-investing-in-properties-overseas

Jessica Vomiero and Andrew Russell, “Ipsos poll shows Canadians have concerns about immigration. Here are the facts,” Global News, January 4, 2019. https://globalnews.ca/news/4794797/canada-negative-immigration-economy-ipsos/

Lauren Wheeler, “Chop Suey on the Prairies,” Active History, November 1, 2012: http://activehistory.ca/2012/11/chop-suey-on-the-prairies/

Michelle Wong, director, Return Home (Montréal, NFB, 1992): https://www.nfb.ca/film/return-home/

One comment on “#592 Ginger beef and fried macaroni”

Such a wonderful and wise review. Thank you so much for the care that went into it.

Comments are closed.