#565 Postwar Germans

Harold Rhenisch reviews two books:

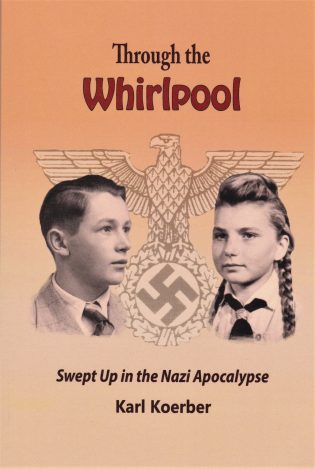

Through the Whirlpool: Swept Up in the Nazi Apocalypse

by Karl Koerber

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2019

$15.85 / 9781718958524

*

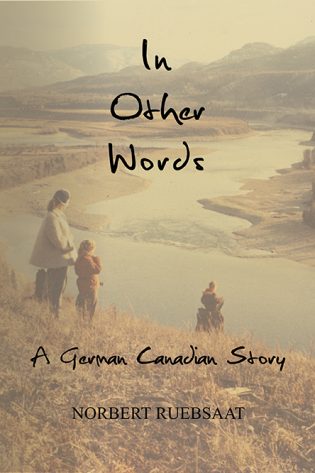

In Other Words: A German-Canadian Story

by Norbert Ruebsaat

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017

$16.20 / 9781547129027

*

British Columbia is a popular place with Germans. Before Expo 86 helped open the province to Asian investment and immigration, perhaps fifteen percent of British Columbians were descended from German families. My mother’s family came in 1929, to join an agricultural commune in the Okanagan.

I mention this only to place Karl Koerber and Norbert Ruebsaat’s books in context. From the 1920s to the 1970s, there was a kind of satellite German colony in the Penticton area. During the Second World War, there was even a Nazi-appointed Gauleiter, a regional Nazi administrator, in Summerland, waiting for German victory. Most Germans had nothing to do with him.

Into this mix, Koerber and Ruebsaat’s families came after the war, to the expanding rural-industrial country of the Kootenays. This story of immigration continues through the present, yet now, as always, Germans don’t make a big splash about their presence. They prefer to vanish and become Canadian. Whole regions of Vancouver, solidly German in the 1960s and 1970s, are now Asian, and their Lutheran churches are Korean and Chinese.

The Germans didn’t leave. They just stopped being German. With the violent German government of the 1930s and 1940s using ethnic culture as an instrument of control and oppression, few wanted to take on an ethnic identity in the Canadian multicultural fashion and chafed whenever attempts were made to lay one on them.

Out of this great vanishing, or this great integration (your choice), a number of German memoirs have been written and quietly self-published over the years, in both German and English, including, for example, my The Wolves at Evelyn: Journey through a Dark Century (Brindle & Glass, 2006) and Hugo Redivo’s Casa Miralago (Okanagan Bookworks, 2005).

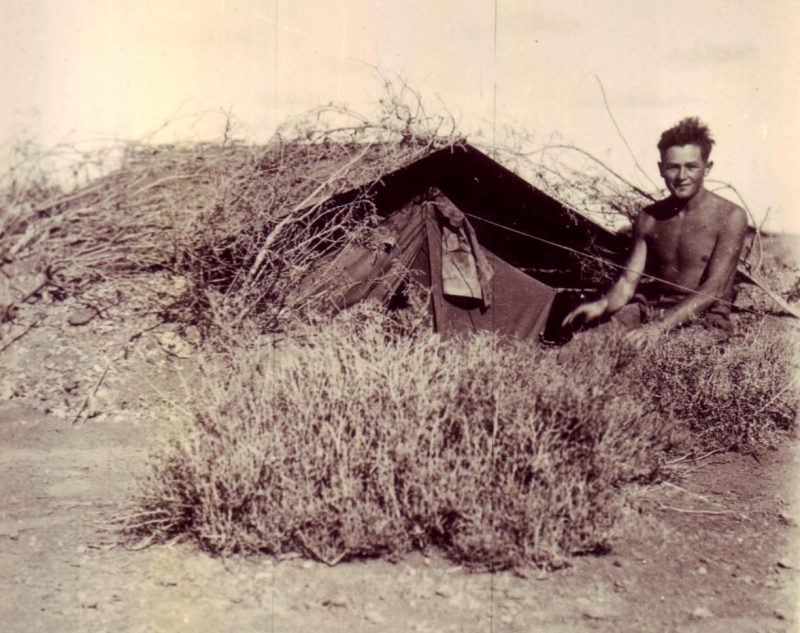

Redivo, the photographer who defined the Okanagan for a couple of generations on an Italian-German foundation, considered himself “the only soldier in World War II who never fired his rifle, even in practice.” Like Karl Koerber’s father, he became an Allied prisoner in North Africa. Like him, he found his way into freedom, of a kind more romantic in imagination than reality, by moving to British Columbia.

The newest in this long series of near-secret memoirs are Koerber’s and Ruebsaat’s. They are quite different books. Karl Koerber is deeply troubled by the Nazism and the Second World War. He has carefully and thoroughly researched Nazism in many books of popular history, searching for some explanation of how his parents, the kind people he loved, could have been swept up in something as horrible as the Nazi Movement. As a result, his book is a compact history of the Second World War and its beginnings, placing family history, love, marriage, adventure and struggle, within the political realities it was given. Throughout, he works to separate the lives of his parents, obviously gentle people, from the regime they supported.

Ironically, the two weakest historical resources he has are his parents. They rarely spoke about these issues. For them, a Nazi past, however weak, was not a stain. It was a fair German attitude: almost all Germans have a Nazi past. They simply had to move on.

Not so Karl Koerber himself. As the true Canadian in his family, he struggles with this legacy. It is only near the book’s close, after his fair and thorough history of the Nazi Period, that he can write, “In 1964, my parents became Canadian citizens and began exercising their right to vote. Any lingering sense of ostracism diminished and finally disappeared completely. We became just another swatch in the Canadian mosaic.”

Koerber is troubled enough by his legacy to gloss over the point that this coming-together and integration was as much British Columbian as German-Canadian, which means, perhaps, that he didn’t need to worry. The two cultures grew up together. He was in good and generous hands throughout.

*

Norbert Ruebsaat’s memoir is less historical and more poetic, as befits one of B.C.’s prominent poets of the modern age. It provides a warm counterpart to Koerber’s cultural wrestling. It is the story of a young German boy in Canada, speaking of his new country and the troubles of integration through the lens of fairy tale. There’s lots of room for that. Ruebsaat’s father was a doctor who retrained in Edmonton to receive Canadian medical accreditation, before taking up a practice in the Kootenays.

While his parents were at work to keep the family afloat in this difficult period, the pre-school children Norbert and Ulrike (Rika) were on their own, looking after themselves. The world of fairy tale that Norbert used to guide them would have led to multiple disasters if not for the generosity, indulgence, and lack of judgment of their Canadian neighbours.

The pattern stuck. In the end, Norbert wrote his memoir of becoming a Canadian in two voices: that of the child, painfully lost in a confusing but nonetheless innocent and beautifully-integrated world, and that of the adult Canadian, placing that lost yet strangely prescient and wise child within the larger context of a family and a country.

Still, there’s much in common with Koerber here, including this bittersweet observation: although these stories of the troubles, failures, and modest successes of integration are vital to an understanding of British Columbian culture, because of the success of Germans at vanishing into the woodwork, they stand out as strangely foreign to British Columbian culture today. That’s integration for you.

If you look for German-language books in British Columbia today, you will find the proud collections of professors of German Literature, and all of their still vital cultural history, in the locked basement of MacLeod’s Books in Vancouver. The first floor is rich with novels, mostly American. It might have been different, had Ruebsaat and Koerber written their memoirs in the early 1970s, when British Columbian culture was a proud European mosaic and J. Michael Yates published his visionary multi-language anthology of B.C. literature in its unofficial immigrant languages: Volvox.

What Norbert Ruebsaat and Karl Koerber have given us instead is a gift from the past, documents about the power of love and memory, and a reminder of how strong the drive is in the human heart towards integration and forgiveness. It is only sad that they had to write them at all.

*

Harold Rhenisch is the author of thirty books, including two books of immigrant experience, Out of the Interior: The Lost Country (Ronsdale: 1994) and The Wolves of Evelyn: Journey Through a Dark Century (Brindle & Glass, 2006), which won the George Ryga Prize. As a boy, he refused to wear lederhosen and was the target in the daily re-enactment of World War Two in the playground of his elementary school in the Similkameen. In 2017, he took his father to Germany and together they triumphantly set the Second World War to rest. He lives in Vernon.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster