#520 Somewhere inside the rainbow

The Afrikaner

by Arianna Dagnino

Montreal: Guernica Editions, 2019

$20.00 / 9781771833578

Reviewed by Alan Twigg

*

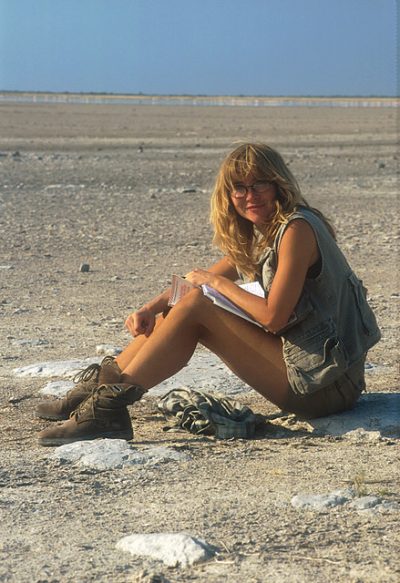

In Arianna Dagnino’s The Afrikaner, a brave and resilient woman ventures to the Kalahari Desert to find her place in Rainbow Nation. The novel arises from the author’s five-year stint as a journalist in South Africa during the late 1990s. Coincidental with its release, it is reviewed by Ormsby Review co-founder Alan Twigg — Ed.

In Arianna Dagnino’s The Afrikaner, a brave and resilient woman ventures to the Kalahari Desert to find her place in Rainbow Nation. The novel arises from the author’s five-year stint as a journalist in South Africa during the late 1990s. Coincidental with its release, it is reviewed by Ormsby Review co-founder Alan Twigg — Ed.

*

In today’s holier-than-thou literary climate, the rising tide of self-appointed purists and keen-to-conform academics could very well demand that all South African novels should henceforth be written by non-whites to offset centuries of settler colonialism.

That would deny us Arianna Dagnino’s long-delayed debut novel, The Afrikaner, a sincere invocation to seek personal truths, incorporating race and politics and history—and culminating with a naked swim in Zanzibar at daybreak.

The Afrikaner begins with a carjacking in Johannesburg during which a white victim describes himself being shot and killed by vicious blacks, all recorded in the present tense. It’s 1997, only four years after Archbishop and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Desmond Tutu has coined the term Rainbow Nation in the wake of South Africa’s first fully democratic election.

The post-apartheid narrator for three pages, Dario Oldani, was a brilliant, young palaeontologist determined to work away from the fundable research hotspots in East Africa (Kenya, Tanzania), hoping to discover the cradle of humankind might be in South Africa or Namibia instead.

The Afrikaner of the title turns out to be his grief-stricken lover and colleague, Zoe Du Plessis, who, despite being from a deeply entrenched white family [the word Boer is avoided], is little concerned with money, status or personal appearance. Instead she seeks belonging.

“Her life is no different from that of many other white-born children of this continent: She invaded Africa, grew in her womb, was raised by her and learned to love her as if she were her real mother, no matter how dysfunctional the womb might turn out to be.”

Zoe gains permission to continue Dario’s dig in the Kalahari, across the border in Namibia, grateful to leave her liberal and ambitious brother to manage the family’s venerable wine business.

A fellow palaeontologist has once suggested it would be easier for Zoe Du Plessis to give herself to an Australopithecus than to a man in the flesh. “Only Dario succeeded in breaking her subliminal veto.” But our protagonist is no prude. Rather, Zoe has gleaned that romantic love is dangerous for first-born daughters of the Du Plessis clan due to a curse thrown at a male family member by an old Xhosa diviner during a massacre that happened in the year 1801. “White Man! From now on, the first-born females in your family will see their men die before producing offspring.”

Zoe learns all this from diaries and letters written by a succession of first-born aunts dating back to the late 19th century. She is also spooked by having witnessed, at age thirteen, the rape of her family’s beloved mixed-blood maidservant, Georgina, in the kitchen, by Georgina’s boss. At the time, Georgina pleaded with Zoe not to tell. The victim and perpetrator remain in the employ of Zoe’s brother, who is none the wiser.

That’s the set-up. Woe is Zoe.

Unfortunately, the abstract painting on the book jacket provides zero information as to what the story is going to be about, so one could argue that, despite a promotional video, this debut Canadian novel, by an Italian-born journalist who teaches at UBC, is unlikely to gain a lot of traction. That said, as soon as we get to ride along with Zoe towards the Kalahari where, as Dario once noted, muscles relax, the mind expands and ‘our’ time dissolves, Zoe’s grief becomes transformative, and we’re hooked.

The Afrikaner becomes a convincing and deeply moving account of how a brave woman is determined to take “her first steps out of the cage of her Afrikaner heritage” to feel she is a necessary and good part of the new Rainbow Nation.

*

Early on, Zoe has recalled a brilliant black man she knew in London during the 1980s. Thabo Nyathi had moved to England thanks to a scholarship that allowed him to bypass the Bantu Education system which prevented Blacks from attending white universities. Zoe and Thabo both applied for a new research unit at Witwaterstand University. What happened next is worth quoting in its entirety.

“The choice fell on her — a Du Plessis — and Piet de Vries, another thoroughbred Afrikaner. Thabo, the best among the candidates, didn’t make it. He accepted the verdict with composed dignity. She accepted the posting without venturing to say a word in his favour. They both knew Thabo would be precluded from any further career in the field of paleoanthropology, at least in South Africa.

“At that time, not even academia, supposedly the patron of broad-mindedness, was ready to open its doors to blacks. But even out there in the bigger world, Zoe asked herself then, conscious of this injustice: How many black paleoanthropologists were there? Did they exist? Did they have a voice? Did they publish books? Although the largest number of hominid fossils had been found in Africa, she was not aware of any paleoanthropological research team headed by a black. As in the golden age of safaris, the white bwana commanded and the black porter looked after the luggage.

“She hasn’t heard from Thabo since then. But she has never forgiven herself for having kept quiet. The moral wrong has seeped into her, day after day, digging into her. To no one has she confessed her cowardice. For years she has felt this infamy burn inside her. She’s no better than other Whites who, being in the know, kept their mouths shut; who, at seeing a black kicked or whipped with the sjambok, have turned their head away. This sick feeling about herself has grown within her like a consuming cancer–it clogs the pores, deadens the heart.”

This is the voice of the person we are glad to follow into the desert.

Just as Frida Kahlo was deeply distraught by her inability to have a child, and turned that angst into art, Zoe Du Plessis’s woe drives her to dredge up intimate honesty with herself while she and her racially diverse crew assiduously hunt for fossils. The latter professional enterprise is ostensibly what drives her to avoid society but Zoe knows scientific celebrity is the product of sheer luck almost as much as expertise. “What we are looking for are needles of Palaeolithic evidence in the haystack of Africa.”

Near an encampment of twenty San Bushmen people, in charge of men under strenuous circumstances, able to have a brief shower only once a week, Zoe proceeds to explore her place in South African society, contemporary and otherwise, with an unflinching candour that makes The Afrikaner increasingly engaging.

“Zoe feels an instinctual bond with the San people and the Coloured in general. It isn’t always the case with the Blacks, she now admits to herself in dismay. She grew up in Africa but she doesn’t know them. There are millions of them in her country, yet–except for her interaction with a bunch of researchers and medical students–she hasn’t shared much with them.”

One of those barren aunts has advised another aunt in a letter that there are many ways to make life meaningful without a man’s love. In the latter half of this novel, we share Zoe’s resolve to discover her own rightful place in South Africa, with or without a man, so she can no longer feel like a prisoner inside her family’s plotline, “trapped in a cage of predestination, with invisible bars and no rescue plan.”

The Afrikaner boldly includes a lengthy dinner table conversation, hosted by a famous writer, that is unabashedly intellectual. It resembles that long, dinner table sequence that was cut from Apocalypse Now for its theatrical release, a scene in which Martin Sheen is hosted by French post-colonialists who dissect the historical backdrop of Indochina prior to the Vietnam War. “Your fortress becomes a prison,” the writer tells Zoe, “once you have swarms of desperate people pressing at the gate.” Just because he can sometimes appear arrogant doesn’t mean he isn’t right. Much to her surprise, Zoe becomes curious to know more about him.

*

To say more is to give away too much. The Afrikaner is far from a perfect construct; but, hey, look at Under the Volcano. In Crying, Roy Orbison goes dreadfully flat. Schubert’s symphony was never finished. Art must be cathartic, original and memorable.

Dagnino’s omniscient and yet deeply personalized narration, in the present tense, can often seem clumsily at odds with the frequent insertions of private letters, but if the reader perseveres, the novel pays great dividends as soon as Zoe’s begins her exodus to the Kalahari.

North Americans have gleaned a deeper awareness of South Africa through Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country, Sir Laurens Jan van der Post, Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee. We’ve also seen Invictus or A Dry White Season or Richard Attenborough’s Cry Freedom about Stephen Biko, the man that Nelson Mandela described as “the spark that lit a veld fire across South Africa.”

The Afrikaner deserves its place in that pantheon.

*

Alan Twigg is a freelance writer. In the fall of 2029, Ronsdale Press released his 18th book, Dr. Aall: Sixty Years of Healing in Africa, about a Canadian physician who pioneered treatments for epilepsy in rural Tanzania.

Alan Twigg is a freelance writer. In the fall of 2029, Ronsdale Press released his 18th book, Dr. Aall: Sixty Years of Healing in Africa, about a Canadian physician who pioneered treatments for epilepsy in rural Tanzania.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster