#493 Canadian maps that mattered

A History of Canada in Ten Maps: Epic Stories of Charting a Mysterious Land

by Adam Shoalts

Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2018

$22.00 / 9780143193982

Reviewed by Graeme Wynn

*

The universe is made of stories, not atoms.

The universe is made of stories, not atoms.

American physicist Sean Carroll once used this line by American poet Muriel Rukeyser as a springboard for his claim that: “There is more to the world than what happens; there are the ways we make sense of it by telling its story. The vocabulary we use is not handed to us from outside; it’s ultimately a matter of our choice.”[1]

These words were brought to mind, somewhat perversely, by my encounter with Adam Shoalts, A History of Canada in Ten Maps. First published by Allen Lane in 2017, it was designated one of Macleans magazine’s six “must-read” books for November of that year. In 2018 it was long-listed for the RBC Taylor Prize. It later received the 2018 Louise de Kiriline Lawrence Award for Nonfiction, and was shortlisted for the 2018 Edna Staebler Award for Creative Non-Fiction. Widely-reviewed in newspapers and magazines across the country, it soon became a Globe and Mail national bestseller and something of a publishing phenomenon. Its author, earlier hailed as “Canada’s Indiana Jones,” and called one of the country’s “greatest living explorers,” on the strength of his exploits recounted in Alone Against the North (Viking, 2015), is probably coming to a literary festival near you this summer.

Telling the story of Canada through maps is an idea that appeals to me. “Show me a geographer who does not need them [maps] constantly and want them about him, and I shall have my doubts as to whether he has made the right choice of life” opined Carl Sauer, perhaps the greatest geographer of the twentieth century.[2] I find maps (especially in their traditional printed, and often folded form) a source of delight as well as information. They provoke questions, spur the imagination, and offer hidden surprises. Because maps are not the territory they invariably conceal stories beyond those embedded in the landscapes they depict — stories about the how and why of their production, and about choices made and emphases placed in that process — that invite further contemplation and reflection. Adam Shoalts clearly shares this fascination and enthusiasm. Maps, he understands, are cultural artifacts. In addition to representing particular pieces of land or sea, they provide a glimpse into the worldviews of those who made them: “what they may have valued and what they didn’t, what they desired and what they didn’t” (p. 2).

For all that, the years have revealed that not all people feel the same way about maps. Many of those I know find traditional maps cumbersome, frustrating, and almost useless. Unschooled in cartographic conventions they struggle with orientation, are distracted by “extraneous” detail, and detest the prospect of refolding the document. Despite the niche appeal of pursuits such as orienteering and geo-caching, most people today are probably relieved to encounter maps as interactive digital files on their phones or tablets. Hit the right keys and Mr. Google’s map division will drop a flag on the location you seek, then issue voice commands about the distance you should travel and the turns you should make to reach it. These maps are the perfect tools for our times: they provide answers rather than invite reflection; they offer solutions instead of stories.

How then to account for the great success of Ten Maps — especially in light of the many previous (and generally less-celebrated) attempts to place maps near the centre of stories about Canada? Various possibilities come to mind. Perhaps the answer lies in the particular choice of maps? the structure and content of the book? the style rather than the substance of the volume? the charisma of the author? the zeitgeist of our times? the strategies used to promote the book? Perhaps it is to be found in some combination of these considerations. Broaching these questions reveals something of the choices that went into the making of Ten Maps and its climb onto the bestseller lists — and suggests some not entirely comfortable things about the nature of our collective choices.

We live in an age of lists. Schools and universities are ranked in “league tables.” People of a certain age are expected to have a “bucket list.” Even the world’s most respected newspapers carry “promoted links” enticing readers to discover “The 10 Most Legendary Investors Who Have Ever Lived” or “11 Best Soccer Goalkeepers in the World.” Jordan Peterson has given us 12 Rules for Life, and our former Governor General Twenty Ways to Build a Better Country.

Perhaps there is special allure in the prospect of ten maps encapsulating the “stuffy” history of Canada. But Shoalts is curiously unforthcoming about the reasons behind his choice of maps. His introduction notes that “they tell stories — stories of adventure, discovery, and exploration, but also of conquest, empire, power, and violence.” He knows that “few maps are wholly innocent” and avers that “the interesting ones usually aren’t.” But are these the “most legendary,” the “best,” the most interesting, maps of Canada? Shoalts offers no such justification. Nor does he explain his choice of this double handful, rather than eight or fifteen or, instead, a completely different selection.

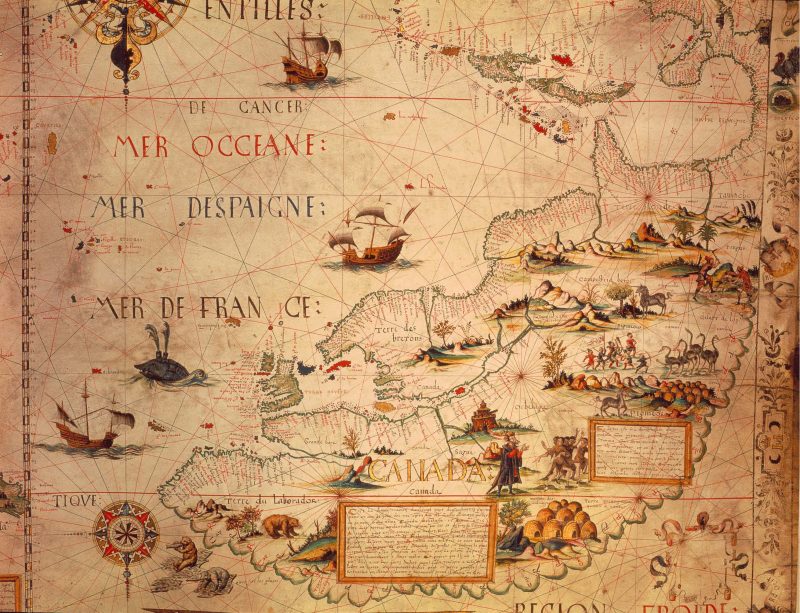

The maps at the centre of this book date from 1690 to 1828. The earliest is a copy of the Skálholt map (made a century or so earlier), incorporating knowledge of the coasts west of Greenland acquired by Norse voyagers about 1000AD. The most recent was published with John Franklin’s account of his second overland expedition to the Arctic. Between these we have the CANADA section of Desceliers’s world map of 1550; Champlain’s map of New France (1632); Bellin’s map of New France (1755); Peter Pond’s map of the lakes and rivers between Lake Superior and Slave Lake (1790); Samuel Hearne’s map of the Coppermine River (1795); Alexander Mackenzie’s “Map of America,” showing his great northern and western voyages (1801); David Thompson’s giant map of the territory between Lake Superior, Hudson Bay and the Pacific coast (1814); and an 1815 copy of the Romilly and Philpotts map, made a year earlier, of the siege of Fort Erie.

Most of these maps are reasonably well known; versions have been more or less readily available on the internet for some time. The Romilly-Philpotts map of the Niagara peninsula aside, most of them cover considerable expanses of territory; their physical dimensions vary greatly, from the 26 cm by 21cm of the Skálholt map to Thompson’s 500 cm by 300 cm display. Three (the Skálholt map, Desceliers, and Bellin) are by mapmakers intent on consolidating and presenting geographical information derived from earlier voyages. Six are ascribed to particular individuals who were themselves explorers, though the physical production — the cartography, engraving, and printing — of the maps reproduced in the book was, variously, the work of others.

All of these explorers’ maps included material derived from other sources, but each of them reported information derived from epic overland/ canoe voyages undertaken by their authors. Against this backdrop, the Fort Erie map is an outlier. Produced by Royal Engineers rather than intrepid voyagers, its theme is conflict rather than “discovery.” “Explorers might make the first maps, but the final ones are usually made by armies” runs Shoalts’s opening sentence in his discussion of “Canada’s Bloodiest Battlefield” (p. 246).

Still, questions remain. Canada, as we think of it today, came into being gradually, after 1867. Of course the name was used earlier (as Desceliers shows us), to characterize the area also known as New France, and then, after 1791 in the names of the colonies of Lower Canada and Upper Canada. But in 2017 – the 150th anniversary of Confederation – it is passing strange to find a “History of Canada” (in maps or otherwise) that effectively comes to an end in 1828. A “geographical history” of Canada might well have used maps to chart the expansion of Canadian territory “From Bonavista/ To Vancouver Island, / From the Arctic Circle/ To the Great Lakes waters.” But even this would hardly stand as a history of the country.

This book is not the “History of Canada” it claims to be. Shoalts over-reaches when he says that the explorers and voyageurs who are at the heart of his account “created the modern Canada we know today” (p. 302). The small print at the foot of Shoalts’s title page indicates that the book offers “epic stories of charting a mysterious land” — and so it does. Moreover, the “ten maps” are not integral to the story told here. They serve, instead, as foils to Shoalts’s overriding interest in exploration and discovery, his admiration for those who forged into “the unknown” parts of an often harsh and brutal land, and his own persona as an “expeditioner.”

Shoalts writes a vigorous prose. Consider a few of his chapter-opening sentences: “The ship under sail pitched and swayed as a bearded warrior gazed across heaving seas at fog-bound cliffs” (here come the Vikings, p. 21); “Inside the palisaded walls of the little wilderness fortress, a severed head impaled on a pike stood as a grim warning” (don’t cross Samuel de Champlain, p. 72); “It was a fine spring morning in 1652 when twelve-year-old Pierre Espirit Radisson set off for some duck hunting with two friends” (only to be captured by Iroquois, to be tortured, to escape and become a fur trader, and to contribute, perhaps, a little information to Bellin’s map, p. 111).

Revealingly, the discussions that follow these openings dwell on the journeys, challenges, and hardships of those whose explorations eventually yielded information systematized on maps. Generally, the maps themselves go unremarked until the last few paragraphs of each chapter, and then they are given cursory treatment. So Radisson’s adventures lead on to those of Louis Jolliet, La Salle, Henry Kelsey, and La Vérendrye, until the talented cartographer Jacques-Nicolas Bellin compiled his map from “knowledge derived from generations of French explorers.” This map, Shoalts observes, conveys an “often hazy sense of what qualified as Canada” and includes an immense blank space marked “these parts entirely unknown” (pp. 136-7).

These sentiments seem to lead, quite “naturally,” to the final section of Shoalts’s book. There he writes: “If there has been one constant throughout Canada’s history, it’s been our wilderness. Vast, forbidding, mysterious, at times both grim and enticing….[it] was the stage for the great dramas of Canada’s past…The wilderness, much more than hockey or the canoe or some bland modern platitude, is the real soul of Canada” (p. 303). Canadians, he suggests early in his book, have possessed something of “the spirit of the Vikings, their restless wanderlust, their desire to seek the unknown and probe the world’s mysteries” (p. 48). But as “the scope of our maps” has expanded, the wilderness and “the scope of our imaginations” have contracted. Forests fall to gargantuan machines, individual tree species to aliens such as the emerald ash borer; hundreds of plants and animals have been extinguished or endangered by the march of settlement. And the process continues. What, Shoalts asks, “would a Canada without true wilderness be like?” (p. 305). His solo trek across the Arctic in 2017, ostensibly undertaken to “celebrate Canada’s 150th Birthday” was, he concedes, less about the past than an act of mourning for the future.

There are vivid and insightful descriptions of exploration in these pages. Shoalts the modern day adventurer knows what it feels like to battle the elements, to endure exhaustion, to suffer despair, to be spooked by unanticipated sights and sounds, and so on. He has an eye for telling, visceral, moments and is at his best in making tangible the experience and effects of pressing into parts little known. Imagine oneself a member of Dr. Richardson’s group from the Franklin expedition, who “had been wandering the cruel Arctic tundra, gradually becoming reduced to mere skeletal figures — their clothing torn to rags, faces weathered and emaciated, eyes sunken in their sockets, hair long, greasy, and unwashed.” These “virtual walking corpses,” Shoalts continues, “emitted a foul stench, with their gums turned black from scurvy and their yellow, crooked teeth loose in their mouths” (p. 273).

Yet there is little new in these stories. The exploits of the men (for most of those hailed as explorers were men) who entered, described, and mapped Canadian space have been related many times. Dozens of expedition journals have been reprinted, and epic overland voyages have been recounted, in general histories and more extended narratives. Although Shoalts acknowledges the explorers’ reliance on Indigenous guides and recognizes, for example, that David Thompson married a Metis woman, Charlotte Small, who accompanied him on many of his journeys, this is a somewhat old-fashioned Eurocentric, androcentric, uncritical and broadly familiar account of the exploration of Canada. Historians might incline to shelve it alongside, say, John Bartlett Brebner’s, Explorers of North America, 1492-1806 (1933).

True, Shoalts reaches, at the last, for some very current sentiments — might the Haudenosuanee idea “that all North America is a fragile, interconnected ecosystem that humans share equally with plants and animals” offer a new way of looking at the world, a vision that carries us beyond dollars and cents and Gross Domestic Product as the measure of all things? Surely we need such a recalibration. But we need a mechanism to get there and we need it not, as Shoalts has it, simply to “recognize Canada’s remaining wild lands and wild life for the irreplaceable gifts that they are” (p. 306). Here Shoalts’s persona as an adventurer trumps his part as scholar. His devotion to remote spaces leads him to ignore now widely accepted arguments that “wilderness” is not a thing but an idea, that there is no longer any truly pristine place (untouched by human influence) on earth, and that the “unspoiled wilderness” areas of past and present fancy were and are the homelands of Indigenous people.

Reflecting on all of this raises some (troubling) questions about what we (the book-buying public at large) read and why. Does the popularity of works such as this reflect an inclination to hero-worship and myth-making; a fascination with adventure; or a nostalgic impulse? If the latter, is our hankering for seemingly simpler times past, or for simpler narratives, uncomplicated by the fine-grained theoretical affectations of contemporary academia? Do we prefer recitations of broadly familiar stories told in triumphal terms (histories written by victors), to the complexities of multi-focal and multi-vocal accounts acknowledging the experiences of those who suffered and lost as well as those who won?

Or does the answer lie elsewhere? Might it turn less on substance than on style? Certainly Ten Maps is a lot more compelling and accessible, stylistically, than the many academic monographs that parse and elaborate upon various parts of its substance, to offer more complex interpretations of early voyaging and mapmaking in northern North America. This popularization and simplification is also evident in television interviews that have Shoalts pitching his book as a series of stories about wars, violence, mutinies, assassinations, and piracy, to the extent that the maps are “almost drawn in blood.”

Or — might we ask — does the success of books today depend (as with so many other things) on their positioning in the marketplace as much as (or more than?) their content? Cover endorsements from outstanding scholars knowledgeable about the topic have long been part of the book business, but the euphoric blurb by a reporter or celebrity reviewer seems to have become a basic necessity of promotional campaigns in recent years. The 2018 Penguin edition of Ten Maps carries endorsements from Canadian Geographic, The Toronto Star, and the Winnipeg Free Press, calling it “brilliant,” “masterful,” and a “marvel.” None of these words springs immediately to my mind as an accurate characterization.

Then there is the glitzy Youtube book trailer for Ten Maps, 1:43 minutes of dramatic historical images and stirring music cross-cut with pictures of the intrepid adventuring author, announcing five themes: Legends; Mysteries; Empire; Madness; and Obsession. More than this, it may be that the story of publishing success in the WWW-age is less attributable to the content between the covers than to the (generally hidden) digital metadata that publishers attach to their titles, to drive search engines to retrieve and display information about them.

For all the poetic license in Rukeyser’s declaration that stories, not atoms, constitute the universe, there is, indeed, “more to the world than what happens” (or at least what seems to happen). The stories we tell — of past and present and (as dreams) of the future – help us to make sense of who and where we are in space and time. They orientate and sustain us, as individuals and as the collectives we call communities, societies, and nations. They are the maps we create to navigate life. Just as explorers of old provided new information for cartographers to improve their renditions of the world, experience leads us to refine and reshape our understandings of who we are.

Reading Shoalts has reminded me that this is why stories matter, and why we need, always, to be thoughtful about the materials we use and the interpretations we borrow in constructing them. These choices have probably never been entirely free and untrammelled: myths, legends, folklore, unspoken convictions, intellectual canons, political propaganda, and so on have variously shaped the ways in which people have been able to envisage their lives and frame their stories. Shoalts has obviously framed his history in ways quite different from those that I or others might have adopted. The choice was indubitably his to make. Still, there are good reasons to harbour reservations about the tales he tells.

In the final analysis the main contribution of A History of Canada in Ten Maps seems to me to lie not in the stories it offers, but in the vital questions it raises about the role of new digital media in shaping popular understandings of the past and thus inflecting both our sense of the present and our capacity to imagine alternative futures.

*

Graeme Wynn is Professor Emeritus of Geography at UBC. As an historical geographer and environmental historian, he served that institution in various capacities including Associate Dean of Arts, twice as Head of Geography and, for six years, as editor of BC Studies. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, he is currently serving as President of the American Society for Environmental History (2017-2019) and he is Adjunct Professor (History) in the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Wynn currently serves on the Advisory Board of The Ormsby Review and on the Advisory Board of UBC’s Green College. Much of his work has focused on Canada, although his interests extend more broadly to encompass much of the so-called British world. He edits the Nature| History| Society series published by UBC Press, and Spring 2019 will see the appearance under UBCP’s On Point imprint, of a collection of essays, co-edited with Colin Coates, on The Nature of Canada.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Sean Carroll, “Poetic Naturalism,” available at https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/poetic-naturalism/

[2] Carl O. Sauer, “The Education of a Geographer,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 46: 3 (September 1956), pp. 287-299; p. 289.

Comments are closed.