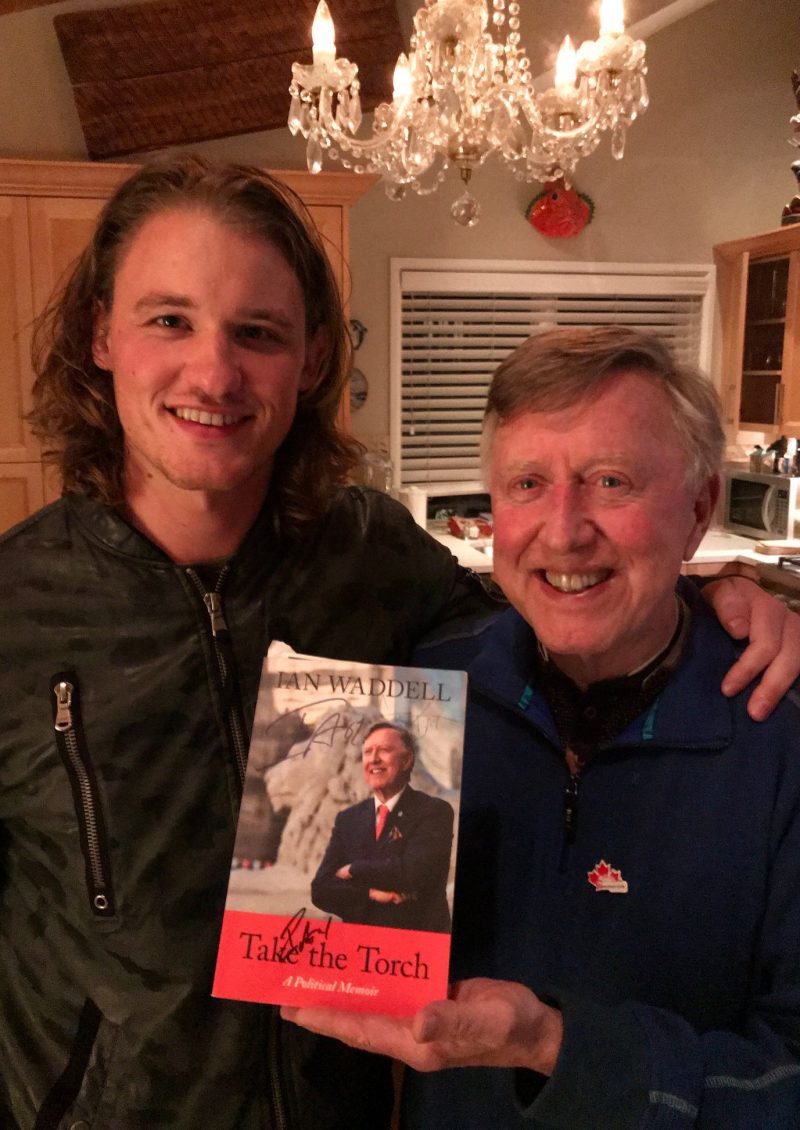

#475 Ian Waddell’s front row seat

Take the Torch: A Political Memoir

by Ian Waddell

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2018

$22.95 / 9780889713475

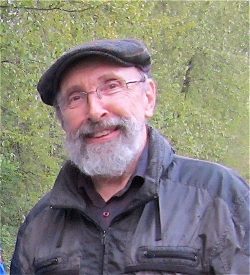

Reviewed by Rod Drown

First published Jan. 30, 2019

*

In Take the Torch, long-time British Columbian New Democratic Party politician Ian Waddell tells, in detail and with humour, the story of how a Scottish boy made good in Canada — and not just for himself. This is a memoir of a distinguished career in federal and provincial politics, the title of which reflects Waddell’s desire to inspire young people to take a more active political interest. Waddell took a leading role in both social awareness and governmental policy-making. Canada’s Indigenous people and women are now thankful for Waddell’s contribution, as are many British Columbians working in artistic, cultural, and sporting fields. Waddell also made a salient contribution to Canada’s constitutional evolution.

In Take the Torch, long-time British Columbian New Democratic Party politician Ian Waddell tells, in detail and with humour, the story of how a Scottish boy made good in Canada — and not just for himself. This is a memoir of a distinguished career in federal and provincial politics, the title of which reflects Waddell’s desire to inspire young people to take a more active political interest. Waddell took a leading role in both social awareness and governmental policy-making. Canada’s Indigenous people and women are now thankful for Waddell’s contribution, as are many British Columbians working in artistic, cultural, and sporting fields. Waddell also made a salient contribution to Canada’s constitutional evolution.

Born in Glasgow in 1942, Waddell had a federal political career as an M.P. (1979-1993) that spanned the governments of five prime ministers (Pierre Trudeau, Joe Clark, John Turner, Brian Mulroney and Kim Campbell), and as an M.L.A (1996-2001) he served in the cabinets of three B.C. N.D.P. premiers (Glen Clark, Dan Miller, and Ujjal Dosanjh). A virtuous exemplar of constitutional and political activism in Canada, Waddell helped change the nature of his — and our — times.

Waddell’s political pedigree reveals that he drove Liberal leader Lester Pearson’s campaign car in the 1962 federal election and two years later met Pearson’s Progressive Conservative archrival and nemesis, John Diefenbaker. This chatty memoir makes clear that Waddell found his feet, and his true progressive political perspective, when as a young lawyer he served as legal counsel to the Berger Inquiry, established in 1974 by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Those of us who came to adulthood in the late 1960s and early 1970s well remember the work that Justice Thomas Berger did in Canada’s north. Berger’s record of responsive openness to the concerns of Indigenous people had a profound effect on Waddell. He recalls how he became a champion of Indigenous rights:

It was not until I was a young criminal lawyer in Vancouver at Main and Hastings that I began to appreciate the tragedies and injustices that enshrouded Canada’s Indigenous peoples. As Counsel to Tom Berger during the Mackenzie Valley pipeline inquiry, I began to see an answer to their plight: Indigenous people could regain political and economic power within the modern Canadian framework through the recognition of Aboriginal and treaty rights (p. 125).

The Berger Inquiry was formed, Waddell writes, because “Arctic Gas, a consortium of the world’s biggest oil companies, wanted to build a natural gas pipeline from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska across the northern slope of the Yukon (near Old Crow) to the Mackenzie Delta, then south along the valley of the Mackenzie River and through Alberta to the United States.” Berger visited all the villages affected by the proposed pipeline.

In a kind of an archival “flashback” to the era, Waddell revisits an article he wrote at the time on the completion of Berger’s session at Old Crow, west of the Mackenzie River Delta. “We finally hear from the young people, the youngest being Harvey Kassie, aged eleven. The Judge listens to him with the same patience as with the older people. He is always polite, never condescending.”

Berger was instrumental in getting good coverage of his hearings – not just to southern Canadians but to the people living in the Northwest Territories. “So it came to pass that the CBC Northern Service provided an hour of nightly primetime coverage throughout the vast Mackenzie Valley in English and for the first time ever, in the Indigenous languages of the Arctic,” writes Waddell. “Coverage in English and French was broadcast to the rest of Canada” (p. 58).

In 1977, Berger’s two-volume report Northern Frontier, Northern Homeland was published simultaneously in English and French. He recommended that a pipeline could be built down the Mackenzie Valley corridor, but only after a delay of ten years, which would allow time for settlement of land claims along the route.

It was not just Ian Waddell who cut his political teeth on the Berger Inquiry. In a postscript he records the later accomplishments of some of the Indigenous principals who took part in the Inquiry’s hearings. Several later became leaders in the territorial governments and the northern political milieu: Nellie Cournoyea, premier of the Northwest Territories (1991-95); Fred T’Seleie, later a proponent of the pipeline (because it moved to include Indigenous people as partners); and Stephen Kakfwi who also became NWT premier (2000-03). Like T’Seleie, he became a supporter of the pipeline. Kakfwi married Marie Wilson, who in 2009 would be appointed as one of the Commissioners of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Two other Indigenous people involved in the Berger Inquiry rose high in the territorial political administration or Indigenous organizations: Jim Antoine became premier of the NWT (1998-2000), and George Erasmus, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations (1985-91) and co-chair of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

After his work with Berger, Waddell went into politics, starting as M.P. for Vancouver-Kingsway in 1979. As an M.P., he had a significant role in Pierre Trudeau’s most memorable achievement: his campaign to bring Canada’s original constitution (the British North America Act) home to Canada from the United Kingdom.

Trudeau, in his effort to create an acceptable Charter of Rights as part of the constitutional process, courted NDP support. Mindful that in the 1980 election his liberals had won only two of 75 seats in the four western provinces, Trudeau held talks, according to Waddell, “with [NDP leader] Ed Broadbent about taking some of our western NDP MPs into the government as cabinet ministers, though we MPs were not aware of this” (p. 119).

Much discussion took place to ensure that the Charter of Rights gave recognition and credence to Canada’s Aboriginal people. Along with fellow NDP MP Svend Robinson and some NDP staff, Waddell concentrated on the Aboriginal rights amendments. The NDP group brought pressure to get their proposed amendments through Cabinet via Trudeau’s loyal lieutenant and Minister of Justice, Jean Chretien, whom he describes as “at first reluctant” (p. 126).

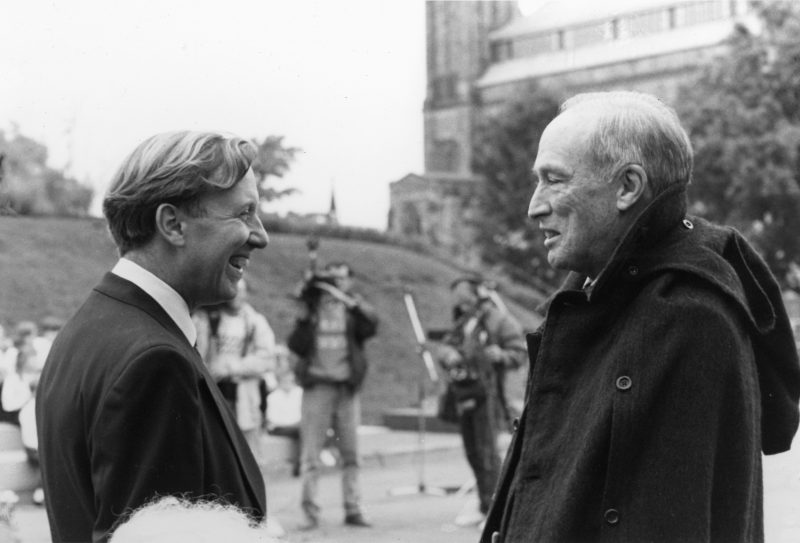

At one stage in the tangled process of achieving the final version of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Aboriginal rights clauses and the women’s equality rights were — incredibly — written out of the document. This omission shocked Waddell, his NDP companions, and his mentor and former employer, Thomas Berger, who was especially forceful in his criticism of the Trudeau government’s removal of the Aboriginal amendments:

No words can deny what happened. The first Canadians — a million people and more — have had their answer from Canada’s statesmen. They cannot look to any of our governments to defend the idea that they are entitled to a distinct and contemporary place in Canadian life. Under the new constitution the first Canadians shall be the last. This is not the end of the story. The native peoples have not come this far to turn back now (p. 129).

Berger’s criticism was not welcomed by the Canadian legal community, many of whom felt it was unseemly and inappropriate for a judge to comment on a political matter. Trudeau was displeased and Chief Justice Bora Laskin also took issue with Berger’s remarks, but Waddell jumped to Berger’s defence. In December 1981, Waddell wrote to Trudeau that: “Your government had the foresight — as it turns out — to appoint him to the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline inquiry which now has given Canada a worldwide reputation as a country that honestly tried to struggle with the implications of development on the frontier” (p. 130).

Eventually, the critical Section 35 – drafted by Waddell — was reinstated and now reads in its four parts as follows:

(1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal people in Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

(2) In this Act, “Aboriginal Peoples of Canada” includes the Indian, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada.

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1), “treaty rights” includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

(4) Notwithstanding any other provision of this act, the aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in subsection (1) are guaranteed equally to male and female persons.

Waddell also recalls the energetic disagreement among leading New Democrats over the very necessity of a Charter of Rights. “Premier Allan Blakeney of Saskatchewan, a highly intelligent and principled man, represented those in the NDP who didn’t like the idea of unelected judges making law, which would happen when judges interpreted a charter of rights” (p. 122).

Waddell’s account of exchanging political memos with Pierre Trudeau in Ottawa shows the nice bipartisan side of Canada’s House of Commons. Policy and even legislation can be discussed behind the scenes by members of opposing political parties. Such communication between opposing politicians may not be as frenzied or as entertaining as Question Period, but it can be effective.

Returning to politics in B.C. in 1996 as M.L.A. for Vancouver-Fraserview, Waddell became Minister of Tourism and Culture. In this capacity he supported the growth of the Arts Club on Granville Island, the purchase and preservation of the Stanley Theatre on Granville Street, and provided significant government support for B.C.’s film industry during the late 1990s. Waddell is also proud of his role in initiating the 2010 Winter Olympics Bid by Vancouver and Whistler.

I have a few criticisms. For those of us who like to skip through text in search of particular political personalities, Waddell’s book could have used an index. More descriptive chapter headings might have drawn the reader into the text more effectively. For example, Waddell served federal constituencies that were wholly or partly located in Vancouver and Coquitlam. Perhaps the titles of a few chapters could have reflected those geographical realities.

I recommend Take the Torch to anyone wanting a first-hand and front-row view of some of the most interesting political events of the last forty years — especially on the federal level. Waddell comes across as both a gentleman and a man on a mission, especially for causes related to the respectful constitutional position of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Take the Torch is also a manual on how to get things done on behalf of the electorate in Ottawa and Victoria — both publicly and behind the scenes.

*

Born and raised in Golden, B.C., Rod Drown attended Simon Fraser University during the 1970s. Since then he has been a farmer, janitor, sawmill worker, journalist, elected regional government representative, and worker in the mental health field. In the 1970s, his poetry was published in a number of Canadian and American literary journals and magazines, including the Dalhousie Review, Canadian Author & Bookman, and West Coast Review. For a few years in the mid-2000s he edited and published an online magazine called Grab News: Muse Views from Vancouver. He also dabbles in writing and recording his own songs. His most recent book, self-published with co-author Ken McIntosh, is No Dog Barked: Who Killed the MacLauchlans? Previous to that, Drown and McIntosh published The 1974 Frasers, the one-term wonder New Westminster minor league baseball team. Currently Rod Drown has three books in preparation: a history of UFOs in B.C., a private detective fiction series based in Vancouver, and a history of Golden’s forest industry. Rod lives in New Westminster.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster