#411 The boy Attorney-General of B.C.

ESSAY: A Person of Some Consequence: Attorney-general George Hunter Cary (1832-1866)

by Robert Ratcliffe Taylor

First published October 31st, 2018

*

Victoria historian Robert Ratcliffe Taylor previously contributed an essay to these pages on the career of the forgotten architect Hermann Tiedemann (The Ormsby Review no. 211, November 26, 2017). Now Taylor turns his attention to another important but overlooked figure of colonial British Columbia.

Taylor assesses the meteoric rise and cataclysmic fall of George Hunter Cary who, after a promising education and early career as a barrister in England, arrived in Victoria in 1859, aged 27, to take up appointments as the first Attorney-General of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia.

“Young Cary began well in the colony,” notes Taylor, but by 1865 he had gone mad. His clerk Arthur Stanhope Farwell found him out of his senses in September of that year, as he noted in his diary: “Sows peas among potatoes at 12 at night with a candle…. Ox bone in one hand and enormous stick in other. Mad as a hatter.”

Taylor assesses the possible causes of Cary’s madness and follows his hasty trip back to England, where his brilliant legal career and many contributions to colonial B.C. ended abruptly with his sudden death in London in July, 1866. – Ed.

*

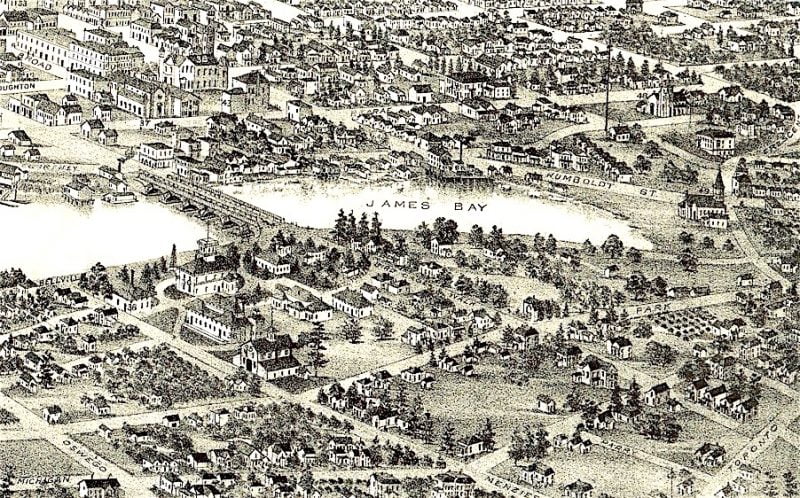

The early days of Victoria, British Columbia, saw a flourishing of vivid personalities such as the journalist and politician Amor De Cosmos, still a well-known figure to local history buffs. British Columbians are less familiar with the name of Vancouver Island’s first Attorney-General, George Hunter Cary,[1] but his seven years in Victoria were a remarkable chronicle of hectic activity and controversy. His choice of a site for his home – now Government House, Victoria — and the legislation he introduced amounted to a not inconsiderable legacy for the province.

In Woodford, Essex, in the United Kingdom, George Cary was born into the professional elite, on 16 January 1832, the eldest of the ten children of William Henry Cary, a general practitioner (b. 1801 or 1802) and Elizabeth Malins. He had an excellent education at St. Paul’s School, London. Then he attended the law school at King’s College, London. Upon graduating, he followed in the footsteps of his uncle, Sir Richard Malins, a prominent barrister. He was said to be a favourite student of solicitor-general Sir Hugh Cairns, who was himself a former student and assistant of Malins. Called to the bar of the Inner Temple on 9 June 1854 at age 22, he moved to Lincoln’s Inn to practice in the Equity Courts, which he did successfully.

On 6 November 1858, he married Ellen Martin. Mrs. Cary was “a small eccentric woman — very pretty,” wrote Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken, Speaker of the Vancouver Island House of Assembly, “witty, sarcastic and her tongue a little venomous,” a feminine counterpart to her husband, who “considered her the sharpest and cleverest woman perhaps ever made.” On one social occasion, however, Judge and Gold Commissioner Henry Maynard Ball found her “savage and rude about some trifle.” Robert Burnaby, although a friend and sometime partner of Cary, detected some social pride in Mrs. Cary, for he wrote that his friend had “a wife who says ‘she was never so ‘igh up a tree before’.” She may, in fact, have been as socially ambitious as her husband. When the couple were ruined, Ball commiserated, “all her ambitious ideas and lofty castles dashed to the ground.”[2]

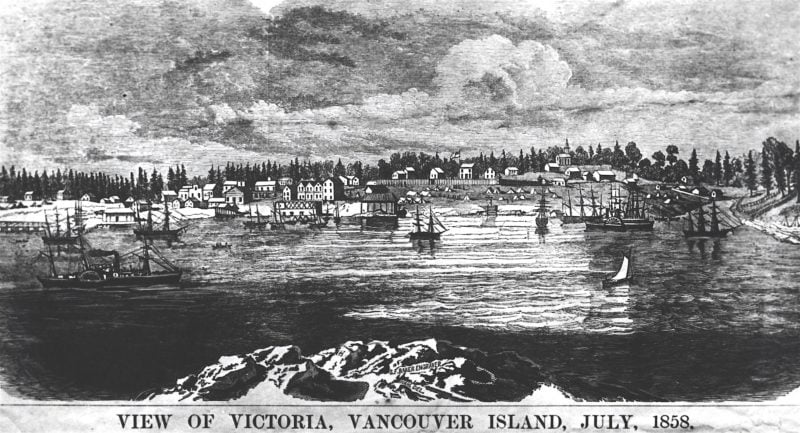

Meanwhile, on Britain’s remote colony on the Pacific Coast, Vancouver Island, Governor James Douglas had appealed to London for well-educated and able men to help administer the other new colony, on the mainland, British Columbia.[3] The 1858 gold rush had swamped both settlements with thousands of outsiders, mainly American, who had little respect for the British rule of law. In response to the Governor’s request, in 1859, the 27-year-old Cary was probably recommended by Cairns to Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, British Colonial Secretary. Some colonists believed that Cary’s relatives recommended his appointment as Attorney-General of B.C. while others claimed that he applied vigorously for the position. Amor De Cosmos hinted that he had connections with the Hudson’s Bay Company.[4]

In 1859, the young couple, who never had children, travelled to remote Victoria. Cary owed unpaid taxes on a house in England, which, he said, he had told his agent to remit to the Board of Inland Revenue. Actually, he seems to have owned two houses there, as well as “two or three outstanding liabilities,” which he had not settled even by March 1864[5] — a hint of the erratic behaviour that was to continue in the colony. It is difficult to know the extent of Cary’s financial resources when he arrived in Victoria. He must have had some savings from his work in England which, along with revenue from his employment in the winter of 1859-60, enabled him to build a mansion, but he was never financially secure.

Young Cary began well in the colony. When, shortly after he arrived in 1859, his name was suggested as a candidate for election in the riding of Victoria Town, his supporters said that they were “confident in [his] ability, independence, and integrity.”[6] Helmcken recalled that Cary was “a very clever lawyer, as sharp as a needle … [with] no end of go and work in him.”[7] Later, in 1864, still confident of his abilities, several of his fellow MLAs introduced a bill in the Assembly which could have made him Chief Justice of Vancouver Island.[8] Cary’s talents also attracted the talented Montague W. Tyrwhitt-Drake, a lawyer and politician, who became his law partner for a time.

Even in 1864, when he had left the House of Assembly and resigned as Attorney-General and his eccentricities were notorious, Cary served on a committee organizing a ball to be held in the House of Assembly on the Queen’s birthday. His name also appears on a list of suggested “stewards” to serve at the retirement banquet for James Douglas.[9] In the same year, Judge and Gold Commissioner Henry Ball noted that, although he was “still in hot water,” he was on a list of invitees to a ball at Government House, New Westminster.[10] Obviously, he still had many admirers. When Cary died in England in 1866, the Daily British Colonist, earlier very critical of him, wrote that, as Attorney-General, “his arguments were respected and his opinions sound.”[11] The Gentleman’s Magazine (London) published an obituary, noting that he “possessed great talent and ability.”[12]

For their part, historians have generally neglected Cary. In the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, however, Victoria historian James Hendrickson calls him “a person of some consequence.”[13] Yet by 1865, he had ended his political career in Victoria under suspicion of corruption, had failed in his business endeavours, and was going mad.

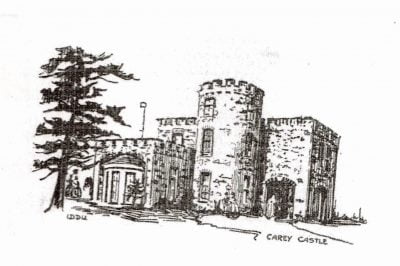

To encounter Cary was to meet a man noted for emotional instability, intemperate language, irrational behaviour, and unscrupulous dealings. He was, according to Helmcken (revising his earlier opinion), “not overburdened with the ordinary ideas of right or wrong.”[14] Even his associate, businessman Robert Burnaby found him to be “a conceited prig of a chap.” Captain Edmund Hope Verney called him “a clever man, but vulgar, unpopular and insincere.” In our time, Professor Hendrickson concluded that Cary was “vain, truculent and eccentric,” and historian George Woodcock wrote that Cary had “the devious arrogance of [. . . a . . . ] self-serving careerist.”[15] He was often the subject of public mockery, most notably when he built his large faux-medieval mansion on a windswept hill on the outskirts of Victoria which was ridiculed as “Cary Castle.”

On the other hand, he did establish loyalties in some quarters, so must have had certain positive qualities. Dr. Helmcken wrote that “we were very good friends.” Henry Ball socialized with the Carys regularly and sympathized with “poor Cary” in his downfall, writing in his diary, “I really am sorry for him.”[16] As well, he seems to have won the respect of his young clerk, Arthur Stanhope Farwell, who recorded attending an “evening party” at Cary Castle in the summer of 1864 and how, on many other occasions later in 1865, he “lunched with Cary,” played billiards with him, or “dined at Cary’s.” On one of these occasions, he found Cary to be “very kind and hospitable.”[17] The 22-year old Farwell may have been impressionable or career-minded, but his often difficult employer did not alienate him. In fact, when the young man had financial difficulties, Cary “promised very kindly to pull me through.” Upon his employer’s unorthodox departure from the colony at Esquimalt in September 1865, Farwell noted that “a great many friends came down to see him….”[18]

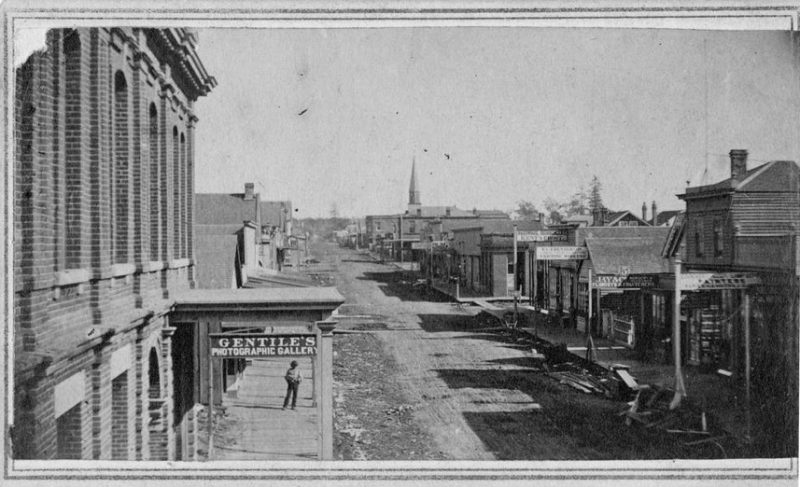

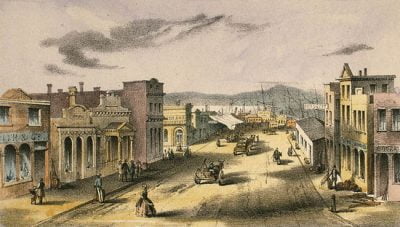

In a frontier town with a small population, sharp personality clashes were bound to occur. Moreover, Cary may have been all too aware of his intellectual superiority over most of his fellow colonists and could not “suffer fools gladly.” No doubt he was struck by the difference between cosmopolitan, sophisticated London where he was educated and had first practiced, and the rugged gold-rush town, going through an economic slump. The mud of Victoria’s streets was alleviated slightly by wooden sidewalks, themselves unreliable and likely to be damaged by horsemen such as the young Attorney-General. The quality which distinguished his personality, however, was a hypersensitivity bordering on instability.

In twenty-first century terms, Cary was a “workaholic,” which may partly explain his irascibility. Restlessly active, he stretched his abilities to the breaking point. The result was that “his rage and despair [were] something frightful to see,” said Judge Matthew Begbie, “if they were not also comical.”[19] This hyper-emotionalism was evident as early as the 1860 election. At a meeting at the Victoria Theatre, Cary “lashed De Cosmos to fury” and got furious himself, making “some slashing remarks.”[20] In the House of Assembly, highly sensitive to perceived slurs, he never developed the tough hide necessary for a politician. Typically on one occasion, reacting to criticism from an MLA, he was “very much excited,” saying, “you shall not attack my veracity or assail my reputation. I shall not allow it.”[21] In 1864, he launched an action against another lawyer for allegedly slandering him. The least of his parliamentary excesses included his “loud laughter,” which interrupted Alfred Waddington’s presentation in June 1860. Also in that year, in response to a suggestion in a court case that he had obtained money under false pretences, he denied the charge and “became very much affected; his eyes filled with tears and his whole frame shook with emotion.”[22]

In the Court House, his behaviour was also considered inappropriate. When the Chief Justice refused a request from Cary, the latter “banged his brief upon the table in a towering passion and shouted that he would never practice in that court until a new judge sat on the bench … [then] … rushed out in the open air to cool his rage.” In 1865 in a case in which the mental stability of the accused was debated, the lawyer Ring averred that the man was not insane, to which Cary relied, “No, but you are.”[23] Ironically, at this time, Cary himself was on the verge of madness.

To what degree his physical health problems affected his emotional balance is hard to determine. He may have been a victim of rheumatism, which produces painful inflammation of the muscles and joints. Thus his emotional outbursts could have been partly due to physical agony — or to the drugs he was taking to alleviate the pain. “Aspirin,” which treats such symptoms, was not invented until 1897 but morphine and treatments containing mercury were popular at the time, both of which could have negative effects of the brain.

Some accounts maintain he had “an eye affliction,” probably iritis, an inflammation of the iris. On the way to Lillooet to practice law in 1862, he was compelled to stop at Port Douglas with “inflammation of the left eye (a chronic complaint),” and had to return to Victoria.[24] In 1865, his secretary, Farwell, gave him a pair of his own spectacles, presumably to alleviate this problem.[25] As his investment in his Cariboo gold mine was failing, fellow lawyer Edward Alston reported that “Cary has come back — very ill — the old complaint in his eye.”[26] These ailments may have been exacerbated by living in his Castle, which was cold and damp. One may also speculate that the arsenic, lead, or antimony in the wallpaper pigments at the Castle could have exacerbated his problems. It might have been a salubrious change, therefore, when, upon his bankruptcy in 1864, George and Ellen moved to “a nice little house en route to Beacon Hill Park” in Victoria, recorded Henry Ball, where they were “very snug and jolly, and feel more at home than in the big house.”[27]

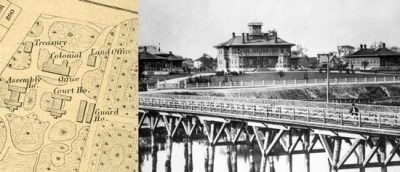

His personality and health issues were not immediately obvious when he arrived in the colony. On 29 April 1859, the Victoria Gazette announced that Cary had been appointed Attorney-General of British Columbia, the mainland colony with its capital at New Westminster. Within ten days after he had arrived in Victoria on 16 May 1859, the young barrister so favourably impressed Douglas that he confirmed him as Attorney-General of Vancouver Island as well. He accepted this dual appointment at no extra salary — a challenging start to his professional life on the west coast and a strain on his personal finances as well as a typically ambitious overestimation of his abilities. He may also have been annoyed to find that in neither colony was there yet a purpose-built courthouse or a structure for the legislature. But young Cary quickly adjusted to his circumstances, finding space for the realization of his ambitions.

Even before Governor Douglas’s appeal for assistance managing the Mainland colony, he had envisaged developing a settlement of landowners similar to English country gentlemen. Pioneers such as John Tod and Roderick Finlayson acquired hundreds of hectares of good land, becoming a buttress to Douglas and the Hudson’s Bay Company — of which most were employees. By the time Cary arrived, most of the best land was taken by these men. The rocky land upon which he would build his “Castle” was not ideal for farming but, aspiring to the life of one of these gentlemen, Cary plunged into landownership. As early as August 1859, he had purchased land in North Saanich. By 1861, he owned about 162 hectares of land in and around Victoria, including three water lots at Thetis Cove, and more on Sallas (Sidney) Island. In February 1860, he was interested in buying land at Port Douglas at the head of Harrison Lake on the route to the Interior. In September 1862, he visited the Comox Valley on Vancouver Island with fifty prospective settlers.[28]

As well, he leased ten hectares in perpetuity on Belcher Street (now Rockland Avenue), outside the eastern precincts of Victoria Town. Here, in 1860 he began to build a manor house on a bluff overlooking the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Its tower and crenellated rooflines reflect the fashion for the “medieval” while the porte-cochère and French windows suggest the country home of an English gentleman. Although compared to many country houses, which Cary would have seen in England, his own home was modest in scale. The mansion’s three-storey stone tower, however, expressed his need to be recognized as not only an important man but as a member of the ruling class. In England, such a house symbolized “glamour, mystery and success.” It would be, in Marc Girouard’s words, “a power house.” Any Englishman who “had made money by any means and was ambitious for himself and his family . . . invested in a country estate.”[29] Such a man was George Cary.

One might have predicted that Cary, wanting to influence government procedure, would have chosen a residence closer to the scene of the action. But the rural surroundings of his mansion may have appealed to Cary’s romanticism and suited his plans for a functioning estate — or to his contempt for his fellow colonists.

According to some sources, construction of a building on the property had been begun by someone else in the early 1850s but was rebuilt by Cary after a fire.[30] As a would-be estate owner, he imported cattle from San Francisco and planted an orchard on the northeast corner of his property. He may also have had plans to expand the mansion but due to his bankruptcy was forced to sell it, the furniture, and the cattle in late 1864.

His manor house was built of rusticated or rubble stone, probably limestone. In 1861, such a quarry existed in Esquimalt, near the new Esquimalt Road, close to the Craigflower Farm. Limestone was also being imported to Victoria from the Santa Cruz quarry south of San Francisco. Building his manor house must have been a drain on his finances. Steam-powered cranes and derricks were in use at this time in the Canadas but, even if Cary’s contractor could avail himself of such equipment on remote Vancouver Island, the work of lifting these stones into place would have been time-consuming and expensive. Hauling or shipping this stone by water would also have been another drain on Cary’s finances. Perhaps he had some ready cash with him when he arrived from England or, in the several first months of his life in Victoria, he earned a good income from clients’ fees and from his government appointment. The need to pay these expenses, however, was probably one of the reasons why he worked so obsessively, which in turn contributed to the decline of his health.

When he arrived on Vancouver Island, young Cary had relatively little professional experience and none of colonial life. It is therefore remarkable that he accomplished so much in the colony in only five years. Part of his success must be attributed to Governor James Douglas’ high opinion of him and consequent support. The governor did not experience his antics in the House of Assembly or in the Court House. Moreover, the older man’s career in the hurly-burly of frontier fur-trading outposts had probably made him tolerant of what he may have considered youthful male hijinks.

In Vancouver Island’s political-bureaucratic system, the support of the Governor would be useful to a man like Cary. Douglas may not have been the autocrat that De Cosmos made him out to be but he had far-reaching authority and influence in the colony. Still, the rudiments of British parliamentary government were emerging. In August 1850, a three-man council for the Island had been appointed including Douglas and two other men. Encouraged by London, Douglas had reluctantly allowed elections for a Legislative Assembly for the colony to take place on 22 July 1856. Seven men were elected as Members. An Executive Council, an advisory body, was appointed by the governor and could include judicial and military men. In this system, the executive was not yet responsible to the elected assembly, but it suited Cary well. A “Supreme Court of Justice” had also been set up for the Island in December 1853.

Agreeing to run for election to the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island, Cary announced a platform on 17 September 1859 which included keeping Victoria’s status as a free port, reforming the land-ownership system, direct and equal taxation, the incorporation of the Town of Victoria, modernizing the judicial system, and defending the rights of the colony against the Hudson’s Bay Company. Obviously, Cary had thought about the state of the Island economy and government and was eager to not only to make his mark but also to improve the colony’s conditions. In the election in early 1860, he won a seat for Victoria Town, which he held until 1863. “Never,” wrote the Daily British Colonist, “had a young man a fairer future.”[31]

Of course, his “new broom” probably also riled some of the colonial establishment and made him enemies. When Cary announced that he would be a candidate in the 1860 election, Amor De Cosmos, as editor of the Colonist, objected immediately, insisting that as Attorney-General, he had no right to do so — and criticizing most of Cary’s proposed legislation. On the other hand, when the Vancouver Island legislature opened in March 1860, Alfred Waddington thought enough of Cary’s qualities to nominate him as Speaker of the House of Assembly. In this session, Cary acted the leader of the government party, expressing their views and policies, which were often his own. No such position as premier existed yet. Nor did responsible government in the colony, which explains why Cary could be both the appointed Attorney-General and an elected MLA. This dual position suited him because he could have the government’s business enacted more easily if he was active in the House of Assembly. His situation led the Colonist to refer to “the Cary Government.”[32]

The young MLA seems to have tried to fulfill his campaign promises. He defended the right of the colony of Vancouver Island to the townsite of Victoria against the claims of the Hudson’s Bay Company.[33] He introduced a bill to regulate the trials of First Nation people accused of crimes; another to introduce an annual registration of voters. In April 1860, he introduced a bill to incorporate the town of Victoria and worked on the Act of Incorporation until 2 August 1862, when it came into effect. Whether or not the great error in wording of this legislation — it did not grant the city the power of taxation! — was Cary’s fault is hard to determine. (The act was revised in 1867.) He introduced another bill to regulate the operation of joint-stock companies and served as Acting Registrar of those companies after the measure was enacted on 27 August 1860. He also introduced and saw to enactment the Real Estate Tax Act (28 December 1860), which levied an annual tax of one per cent on the market value of property on Vancouver Island.

Perhaps the best example of his constructive measures was his reform of the land ownership system. In the fall of 1860, he introduced the “Torrens System,” which became the Land Registry Act of Vancouver Island, passed on 26 August 1861. In London, Sir Hugh Cairns had told Cary about the system, urging him to enact it in the colony.[34] The new law specified that, when land changed hands, an act of registration at a public office was necessary. No longer would the transaction be a solely private agreement between a seller and a buyer. A “Registrar of Titles” or “Registrar General” would be appointed to oversee the workings of the system. A suitable headquarters would be provided for the Land Office — which was housed in one of the new government buildings on the harbour, the “Birdcages.” The Act had thirty-three sections, which gave rise to complaints that it was too long and complicated, but it put landownership on the island colony on a firmer and lasting basis.

Clearly, in Vancouver Island’s second House of Assembly (1 March 1860 to 28 February 1863), Cary was vigorously active so that, at least partly due to his dynamism, the Assembly passed seventy-one Acts in all. Cary did not have a hand in every one of them but his energy and creativity must have galvanized his colleagues. Moreover, this legislation was accomplished while the Assembly had to meet in the new Court House at James Bay, its own accommodations in the “Birdcages” being unfinished. Frustrated with disruptions to their work, the MLAs moved to the old Court Room in the Police Barracks on Bastion Square, a micro-drama that must have made the easily annoyed Cary even harder to get along with.

When he ran in the 1860 election, his inventiveness — and cunning — were first evident. As a supporter of James Douglas, he ran against Amor De Cosmos who was adamantly critical of both the governor and of Cary, whom he saw as Douglas’s spokesman. Victoria’s relatively large population of American Blacks felt a debt to Douglas, who had invited them to the British colony where he had maintained that they would be free citizens of the Queen. Knowing this, Cary told the Blacks that the property-owners among them could vote in this election, an assertion which was not entirely true but which he seems to have hoped would predispose them to support Douglas and hence his own policies. His reasoning was that, since they were not American citizens, then they must be British subjects. Conceivably, De Cosmos’s defeat was partly due to their support for Cary. This “irregularity” did not go unnoticed and contributed to growing criticism of his behaviour.

When he ran in the 1860 election, his inventiveness — and cunning — were first evident. As a supporter of James Douglas, he ran against Amor De Cosmos who was adamantly critical of both the governor and of Cary, whom he saw as Douglas’s spokesman. Victoria’s relatively large population of American Blacks felt a debt to Douglas, who had invited them to the British colony where he had maintained that they would be free citizens of the Queen. Knowing this, Cary told the Blacks that the property-owners among them could vote in this election, an assertion which was not entirely true but which he seems to have hoped would predispose them to support Douglas and hence his own policies. His reasoning was that, since they were not American citizens, then they must be British subjects. Conceivably, De Cosmos’s defeat was partly due to their support for Cary. This “irregularity” did not go unnoticed and contributed to growing criticism of his behaviour.

He did not run for re-election in 1863, probably because his investment in the Cariboo gold fields took him out of Victoria. Conceivably he was aware that he had made many enemies in Victoria so that success at the ballot box might be less likely. At all events, he hoped to make his fortune in gold and to pay for his Castle and to retire on an estate to a life of leisure.

Cary seems to have had a large private law practice, from which one might assume that he had considerable income, an impression that might have arisen from the many cases he argued in the Court House at James Bay. Working only in Victoria, however, was not enough for Cary. He was happy to act as Attorney-General in both the Pacific colonies, although in March 1860 some Mainland residents expressed their opposition to his non-residence in that city. Typically, however, in 1862 he started to practice law in New Westminster and tried to expand his practice into the Interior, venturing up to Lillooet and Lytton. Certain New Westminster residents, however, thought he should be tarred and feathered. Instead, they decided to burn him in effigy and to drown the charred remains. Later, in 1863, they wanted his name struck off the Rolls of the colony of British Columbia “for alleged malpractices.”[35] Undaunted (and unrealistic), he applied again to practice in British Columbia in 1864.

Watching Cary defend a client or cross-examine a defendant would have been impressive because his presentations were flamboyant and strenuous. On 7 June, 1864, for example, he gave “a very forcible address of 2½ hours in duration,” which, given his fragile health, must have been exhausting. Two days later, he “opened the case for the plaintiff in a very able manner” but later “addressed the court in a high-flown style.” At the same time, he had little respect for Chief Justice David Cameron, who had no formal legal training. On one occasion his “disparaging remarks” about the Chief Justice’s procedures led to “utter confusion in the court.”[36] Yet his abilities in the courtroom were prized by many. As late as August 1865, disgraced and demented, and about one month before he left Victoria to return to London, he was still practicing law and defending clients.

Not only would Cary serve as Attorney-General, an officer of the Crown, representing both the Crown and the public in the colony’s Supreme Court and responsible for the organization of civil justice but, because the Attorney-General was also a member of the Executive Council, he would be official legal advisor to the government. With characteristic egotism, George Cary overestimated both his own abilities and the willingness of the public to tolerate his personality and antics. As the Colonist noted, “the Boy-Attorney-General” would be challenged for his apparently grandiose ambitions.[37]

When he was serving as Attorney-General for the Mainland colony, as noted above, concern arose there that he lived on the Island rather than in New Westminster, the capital of British Columbia. When the Home government eventually encouraged Governor Douglas to abolish “absenteeism” in the colonies, Cary was understandably loath to move to New Westminster, relinquish his position as MLA for Victoria Town and, equally important, to give up Cary Castle, which he had only recently had built. And so he gave up his position as Attorney-General of British Columbia, which was, he said, a “bleak and barren region.”[38] As we have seen, this sacrifice did not prevent his later attempting a law practice on the Mainland.

He remained an MLA for Victoria Riding until 1863 as well as Attorney-General for Vancouver Island until 1864. In the summer of that year the new governor, Arthur Kennedy, ordered the auditing of public accounts, a review that found irregularities in his Attorney-General’s records, such as taking excessive legal fees from the government. Kennedy was less tolerant of Cary than Douglas had been and, having found “matters affecting his character,”[39] the governor intimated that he should resign. On 6 August, seeming to comply, Cary wrote to the Executive Council “declining to act any further for the Crown in cases where counsel is required.” The Governor accepted his statement as a resignation from the office of Attorney-General, after which Cary, in a confusion probably reflecting his mental state, wrote that he “had no intention of resigning;” [40] and then, without defending himself, he announced his formal resignation on 20 August 1864.

Upon learning of Cary’s resignation, the Colonist hoped that his replacement would be “a gentleman of integrity, ability and colonial experience, qualities that unfortunately have been ‘conspicuous in their absence’.” In New Westminster, the British Columbian pithily remarked, “A GOOD RIDDANCE,” followed by one sentence noting his resignation.[41]

More accusations followed. On 27 September of that year, the Executive Council learned that the amount of fees received by Cary as Registrar of Joint Stock Companies and paid into the Treasury had been less than it should have been, a deficit of $526.00. On 10 October 1864, the Council felt obliged to threaten legal proceedings against Cary unless he paid that sum immediately.[42] Shortly after this announcement, Cary hired his former partner M.W. Tyrwhitt-Drake as his defence lawyer in case such proceedings were begun.

No record exists of his remitting this “short payment,” but his continuing to work, although in ill-health, suggests that he may have done so. Nor does a formal court case against him seem to have been launched, perhaps because the authorities were aware of his increasing mental instability. At all events, for another year, he was allowed to continue to practice law in Victoria, attracting clients and the loyalty of a few friends.

Although not originally one of those newcomers who were attracted to the west coast colony by the lure of gold, Cary was determined not only to have political influence but also to get rich. He had no business experience in England or in the colony but seems to have had an exalted sense of his own financial acumen. Maintaining his neo-medieval mansion on Belcher Street would have necessitated an expensive staff of servants appropriate to his and his wife’s sense of self-worth. This need to support the “life-style” of a country squire and to supplement his salary as a public servant and a lawyer may explain why he became involved in several business ventures.

His undertakings often had the “optics” of deviousness, which antagonized his enemies. He seemed to be using his position as Attorney-General to further his business activities, while trying to hide such involvement from the public. As an entrepreneur, however, he failed in everything he undertook.

For example, as a putative member of a joint stock company that owned the Victoria Gazette, it was said that he changed the wording of articles that others had written. According to his partner in the enterprise, George E. Nias, he “refused to publish anything complimentary to [David B.] Ring” and “always had a fit of bile when Ring’s name appeared in print.” (Ring, a lawyer almost as irascible as Cary, often clashed with him in the Supreme Court and in the Legislative Assembly.) His connection to the Gazette had to be kept secret because, he was reported to have said, if it became public knowledge, it “would injure me politically.”[43] As with much of Cary’s activities, the details of this case are murky and the ethics on both sides are questionable. Nias claimed that the Attorney-General had not provided his promised share of funding for the partnership. Cary sued Nias for $1103.00 and denied ever being a partner with Nias. The latter accused Cary of perjury, was jailed for debt, and ultimately, although the judge ruled that no partnership had existed, had to pay what Cary claimed was owed to him.

For example, as a putative member of a joint stock company that owned the Victoria Gazette, it was said that he changed the wording of articles that others had written. According to his partner in the enterprise, George E. Nias, he “refused to publish anything complimentary to [David B.] Ring” and “always had a fit of bile when Ring’s name appeared in print.” (Ring, a lawyer almost as irascible as Cary, often clashed with him in the Supreme Court and in the Legislative Assembly.) His connection to the Gazette had to be kept secret because, he was reported to have said, if it became public knowledge, it “would injure me politically.”[43] As with much of Cary’s activities, the details of this case are murky and the ethics on both sides are questionable. Nias claimed that the Attorney-General had not provided his promised share of funding for the partnership. Cary sued Nias for $1103.00 and denied ever being a partner with Nias. The latter accused Cary of perjury, was jailed for debt, and ultimately, although the judge ruled that no partnership had existed, had to pay what Cary claimed was owed to him.

In March 1860, he riled public sensibilities when he tried to buy Victoria’s water supply, which came from the Spring Ridge area. Although in theory the Hudson’s Bay Company owned the land, the spring had long been regarded as public property. Cary tried to finesse the deal as surreptitiously as possible, forming an arrangement with engineer and surveyor John J. Cochrane, who was the public face of their company and who made the actual purchase from the HBC. (Cary’s name does not appear in the advertisements.) When Cochrane began to fence in the spring and charge a fee for use of the water, an outcry arose, especially from the water carriers who regularly came to fill their barrels and deliver the contents to places in the city. One John Montrose tried to tear the fence down. A court case ensued, which Montrose, because he was theoretically trespassing, lost. But the damage was done to Cary’s image — as “The Water Monopolist.”[44] Ultimately, the Hudson’s Bay Company revoked the sale.

The most notorious of his business ventures was his role in the Bentinck Arm and Fraser River Company. (The North Bentinck Arm is an extension of the Burke Channel, about 400 kilometers north of Vancouver.) In 1862, Cary was a partner and “legal advisor” to this enterprise, dedicated to building a toll road from Bella Coola on the Arm to the Fraser River. To this end, the company would acquire land near the mouth of the Bella Coola River where they envisioned a new seaport, with connections to Victoria. Cary claimed that the land between Bella Coola and Quesnel — the territory of the Nuxalk and the Tsilqot’in people — was “empty,” i.e., uninhabited. Indeed, it was nearly empty by 1862, after a terrible smallpox epidemic decimated the First Nations population there.

Cary’s involvement with the Bentinck Arm project raises the question of his allegedly deliberate but covert introduction of smallpox into the area. Recent books[45] have suggested that he sent two men infected with smallpox into the valley with the aim of spreading the disease there, thus emptying the place of the Indigenous population and making it easier for white settlers to move in. It is true that Cary described the area as “empty,” that he would be the main beneficiary of the scheme, and that thousands died of the disease. On the other hand, because he shared with his contemporaries the view that the First Nations were savages, he could have meant that the valley was “empty of civilized people.” No direct evidence exists that Cary deliberately schemed to kill the Indigenous population of any part of British Columbia.

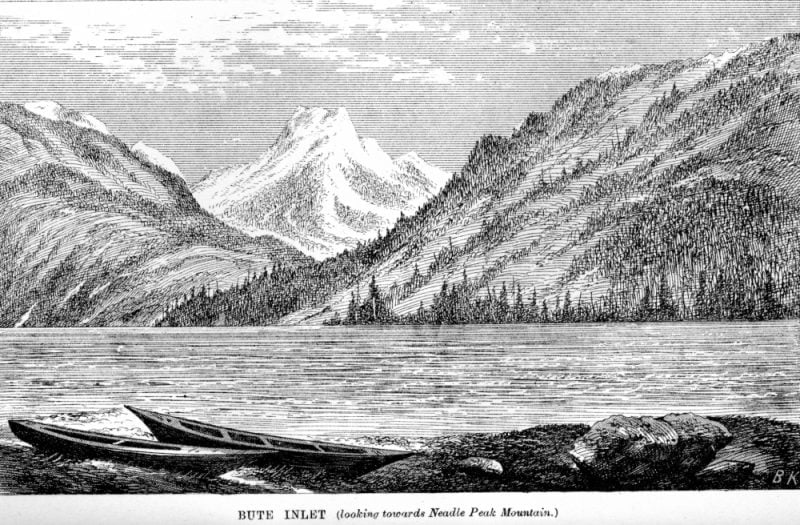

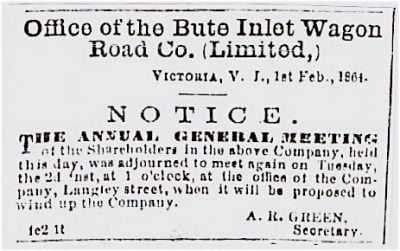

Typically, however, his business tactics were devious. For example, he attempted to play down his involvement in the Bute Inlet Company, advertisements for which cited as secretary A.R. Green, a local import merchant, not mentioning Cary’s role as one of the prime movers. His education and experience, of course, were an asset in avoiding public difficulties. He was the instigator of a lawsuit against William Hood, a contractor on the Bute Inlet project who may have owed the company $20,000. Reading the transcript of Hood’s trial, one cannot escape the sense that this simple man was outmaneuvered by Cary and his colleagues. The letter of the law, however, stood with Cary and so Hood lost the case.

Meanwhile it appeared as if Cary and other investors may have ignored regulations of an Act of 1856. When he was reprimanded by Douglas, who found Cary’s actions close to land speculation and hence illegal, the Attorney-General let his claim lapse. The project never fully materialized and the company was wound up by the shareholders in March 1864.

In 1863, Cary said that, in order to recover from nervous exhaustion, he had to spend some time in the Interior and so took a three-month leave of absence. There may have been truth in this reference to his psychological problems, exacerbated by overwork. His expenditure on his mansion may have drained his personal finances or possibly he needed funds to expand the structure. Certainly he wanted to develop his share in the Never Sweat Mine Company in the Cariboo. In his journal, Henry Maynard Ball says that he warned Cary against “those infernal mining speculations,”[46] but to no avail. Farwell recorded that Cary purchased an interest for “$2000 cash and $2000 in thirty days.” He visited the mine and dug up a panful of gravel himself. When it was washed, it yielded fifty dollars, so that he eventually expected to “clear about $30,000.”[47] Encouraged, he borrowed from friends to invest in the mine.

The Cariboo Sentinel wrote that “the best miners are puzzled” at Cary’s confidence. It was rumoured that the mine had been “salted;” that is, someone had added gold to samples from the mine, increasing its value and thus deceiving its potential investors. Indeed, the mine’s production record was uneven. Throughout the summer of 1863, it was “taking out gold abundantly,” yielding about $40,000. In May 1864, however, the enterprise was “troubled with water,” so the owners installed an over-shot wheel to help in the washing of the gravel. Matters progressed smoothly, although “want of water” was still a problem. Then in September 1865, “one of the greatest freshets that has ever visited Cariboo” caused the mine to cave in, leaving it “in a bad condition.” In October it was “not doing much” and never produced the wealth that Cary anticipated.[48]

The Cariboo Sentinel wrote that “the best miners are puzzled” at Cary’s confidence. It was rumoured that the mine had been “salted;” that is, someone had added gold to samples from the mine, increasing its value and thus deceiving its potential investors. Indeed, the mine’s production record was uneven. Throughout the summer of 1863, it was “taking out gold abundantly,” yielding about $40,000. In May 1864, however, the enterprise was “troubled with water,” so the owners installed an over-shot wheel to help in the washing of the gravel. Matters progressed smoothly, although “want of water” was still a problem. Then in September 1865, “one of the greatest freshets that has ever visited Cariboo” caused the mine to cave in, leaving it “in a bad condition.” In October it was “not doing much” and never produced the wealth that Cary anticipated.[48]

Even here, Cary’s involvement was controversial, not all of it clearly recorded. It was said that at Never Sweat, he held “more claims than he was legally entitled to.” Knowing this, a certain Stenhouse “came to jump a claim” on Cary’s property. To forestall this, the latter quickly sold twenty-one metres of ground before Stenhouse “had staked out the jump,” thus saving most of the actual mine for himself.[49] Ultimately, Cary lost his investment in the enterprise and so, upon returning to Victoria, despite still having a large private law practice, he was bankrupt, a condition in which must have exacerbated his emotional instability and his physical health.

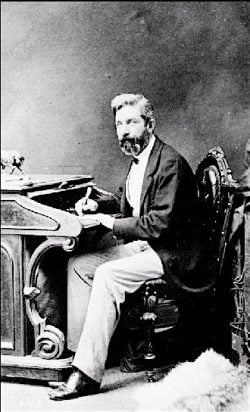

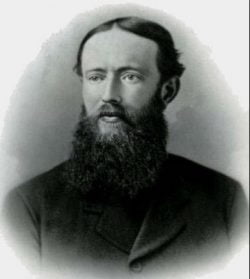

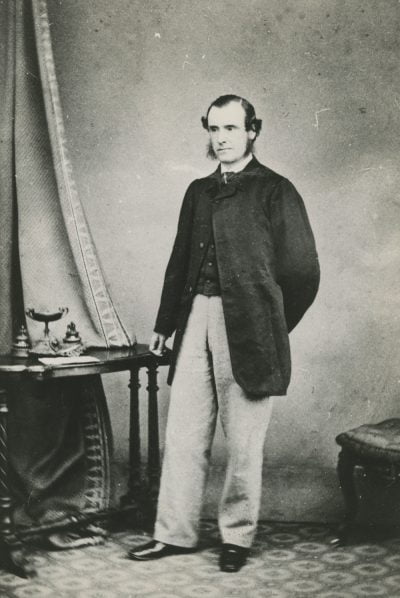

Cary’s mental and physical condition was problematic to say the least. The photograph which accompanies this article is revealing. He seems to have been unable to stand still for the photographer so that his face appears blurred, his expression preoccupied and distant. The memoirist Edgar Fawcett recalled that Cary was “delicate-looking” and appeared ten years older than his actual age.[50] (Ellen, however, looks up at him as a devoted Victorian wife, and in her case probably a long-suffering one.) Outside the Supreme Court and the House of Assembly, Cary’s behaviour was erratic, even violent. It was said that he once assaulted a defendant in the street with a horsewhip. On another occasion, he engaged in a fistfight with a certain Macloughan, enduring “a black eye, etc.”[51] He was fond of horse racing, often betting at the Beacon Hill racecourse. Perhaps he was an unfulfilled jockey himself, for in 1859 he was arrested for riding “furiously” across James Bay Bridge.[52]

As early as 1860 he had become notorious for appearing at the Police Court on various similar charges. For example, he was fined twenty dollars for riding his horse on the Fort Street pedestrian footpath. His reaction was typical. Flaunting his presumably superior legal knowledge — and in a typically long-winded (three page) letter — he claimed that only in England were horses not allowed on the footpath. Moreover, he said, Police Commissioner Augustus Pemberton had “personal ill feelings against me,” “a desire to cause me personal annoyance” and did not understand the nature of his job. The Magistrate, however, held that the laws of England did indeed apply to Victoria.[53] Cary had to pay a fine. On another occasion, he was seen riding “at full trot” over the new Victoria Bridge.[54]

Reacting to critical comments, he was prepared to go to extremes. In the House of Assembly, he often disagreed in the House with David B. Ring so that they “frequently crossed swords” [metaphorically] and “on one occasion came very near spitting at each other in earnest.”[55] In October 1859, he accepted challenge of a duel with Mr. Ring when the latter called him a slanderer and a coward. The encounter was planned for nearby San Juan Island, then considered part of Vancouver Island colony, but the authorities intervened before it could happen and charged Cary with having intended to commit a breach of the peace When he was brought before Justice Augustus Pemberton, Cary maintained that no evidence existed to prove that he had accepted any such challenge. Not convinced, the Judge convicted him “on notoriety,” sentencing him to twelve months in jail or a bond of £500.00 to behave for a year. He refused to post the bond and so was jailed but was soon released on a technicality.

In 1864, faced with bankruptcy, Cary had been compelled to sell what must have been for him a “dream house” and its furniture. (The eventual buyer of the Castle was Mrs. Elizabeth Miles, the widow of John Miles who had worked as a clerk in Colonel Moody’s office in New Westminster.) Despite this wise sale, neither George nor Ellen Cary seem to have understood the reality of their financial situation. Shortly before the Castle was sold, Ellen hoped to let it for £400 and then to be able to retire on £700 a year. In September 1864, however, they were planning to leave for England in the near future. In January 1865, they were still talking about re-emigrating. But in the spring Cary announced that he would to go to the Kootenays although his purpose, like his mind, was not clear. His strange public behaviour, violent outbursts in the Court House and Assembly, and his financial catastrophe so perplexed his friends that they determined on a plan to have him return to England.

Cary’s departure from Victoria in 1865 was described by Arthur Farwell in his diary:

8 September: Mrs. C. came to the office in a tremendous state. Dr. Helmcken had told her GHC was insane, everybody in the place says so. Imagines he has no end of business which is not the case. Sows peas among potatoes at 12 at night with a candle. Buys all sorts of things he does not want and swears he has paid for them when he has not. Bought a gentleman’s dressing gown and gave it to Mrs. C. to wear.

10 September: C. raised the devil about Wren.[56] Ox bone in one hand and enormous stick in other. Mad as a hatter.

13 September: Cary worse. Talking the most awful rot.

14 September: Cary came to the office with a lot of bones in one hand and mushrooms in the other which he was going to make tooth powder of.

Indeed, at about this time, Dr. John Ash certified him as insane. (Ash was a local ophthalmologist who may have treated him for his vision problems.) Therefore, Farwell, Helmcken, John Cochrane, Pemberton, Helmcken and others decided that he must return to England. To this end, on 14 September 1865, they “manufactured” a telegram and a letter, reporting that he was to be appointed Lord Chancellor of the Exchequer.

16 September: . . .went to GHC with H. (Helmcken) Mrs. Cary gave him at 10:30 a letter supposed to have come from Miss Malins, manufactured by Miss Pemberton. He had been gardening, covered in mud. Nothing but shirt and pants on with a bucket of grease on his whiskers. Very much delighted.

. . Mrs. Cary packed up. GHC drew up what he called a Power of Attorney which amused him and kept him quiet. Gave him Telegram which answered admirably. Thinks he will be made Chancellor with £15,000 per annum …. GHC amused himself by writing directions, calling himself Her Majesty’s representative … carriage came at 2 p.m. with Helmcken. Got him in before he knew very well where he was … Got him on board at Esquimalt.[57]

His friends had arranged to pay for his passage on the steamer Orizaba. As Mr. and Mrs. Cary left Victoria on 16 September 1865, they were accompanied by Robert Burnaby, presumably to exercise some control over his unstable fellow passenger. Farwell, his secretary, attended to Cary’s professional matters and sold his furniture and books. He “took away [from Cary’s office] all letters and papers I could find.” Presumably he destroyed them (a loss to future historians). On the 25th, he “wrote to Malins asking for instructions about the law books.”[58]

In the two west coast British colonies, Cary’s departure was ignored by the leading newspapers, an ignominious conclusion to his career.

I have found no record of how Cary reacted when, upon reaching England, he realized that he had been deceived. He died on 16 July 1866, in London, of “paralysis of the brain, caused by over exertion.”[59] Whether this was a cerebral hemorrhage or a result of his rheumatism is hard to know. What is sometimes called “rheumatic fever” can cause damage to the heart, so that he may have died of heart failure. One wonders what he had been “over-exerting” himself about in those few last months in London. Any conclusion is hypothetical.

The reason the political and legal elite of Victoria tolerated Cary for so long is probably threefold. His education, talent, and accomplishments were clearly superior to those of any other lawyer in the colony. He was a favourite of James Douglas, governor until 1864, who had a high opinion of his abilities. Moreover, despite his instability, he had loyal friends who found personal qualities in the man that were not in evidence in his political and business dealings.

His professional accomplishments on Vancouver Island were obvious. James Hendrickson referred to Cary’s “powers of articulation and considerable intellectual ability,”[60] which enabled him to introduce and pilot through the Assembly several important pieces of legislation, much of which has endured in one form or another. Moreover, Cary Castle, the expression of his considerably vanity, became Government House in 1865 and, rebuilt twice, the vice-regal residence has remained on the impressive site that Cary chose for his country estate.

When he died in London, as noted earlier, the Gentleman’s Magazine referred to his “great talent and ability.”[61] The Daily British Colonist in Victoria summed up the local view of the man — “able but eccentric.”[62] In fact, Cary was more than able and more than eccentric. His tragedy was that his professional brilliance was too often overshadowed by his amorality and instability.

*

Robert Ratcliffe Taylor was born and raised in Victoria, B.C. and attended Willows School, Oak Bay Junior and Senior High Schools, and Victoria College. He has a B.A. in English and History from U.B.C., an M.A. in History from U.B.C., and a Ph.D. in History from Stanford. He taught History at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, where he was active in the Local Architecture Conservation Advisory Committee, the Welland Canals Preservation Association and the Canadian Canal Society. He has published in German history, St. Catharines history, and, with Dr. R.M. Styran, the history of the Welland Canals. “Retiring” to Victoria, he has worked as a Docent at the Victoria Art Gallery and has published books and articles on local history. This article on Cary grew out of his research into the “Birdcages,” British Columbia’s first legislative buildings. He is indebted to Dr. Michiel Horn and Dr. Wesley Turner for their constructive criticism and encouragement in the preparation of this article. For a review of his book The Birdcages: British Columbia’s First Legislative Buildings, 1859-1957 by architectural historian Martin Segger, see The Ormsby Review no. 807, April 22, 2020 –Ed.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Occasionally, Cary’s name was spelled “Carey” but the “e” was usually dropped especially later in his career. Maintaining the “e” was Joseph W. Carey (no relation), a businessman and mayor of Victoria 1883-84.

[2] John Sebastian Helmcken, Reminiscences. (ed. Dorothy Blakey Smith) Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1975, p. 177; “all her hopes are gone and blighted,” Henry Maynard Ball, Journal, 5 January 1865; BCARS, MS-0750; Burnaby, Land of Promise. Robert Burnaby’s Letters from Colonial British Columbia, Burnaby: City of Burnaby 2002, p. 105; Arthur Stanhope Farwell, Cary’s clerk, found that he “liked Mrs. Cary” and was “agreeably surprised in her.” (British Columbia Archives [Hereafter cited as BCARS]: AO 1236 Box 2, Arthur Stanhope Farwell, Diary, 27 March 1864); Ball, Journal, 28 December 1864, BCARS, MS-0750.

[3] Two separate British colonies were established on the west coast of North America: Vancouver Island, with its capital at Victoria, and British Columbia, centred on New Westminster or Queensborough near the mouth of the Fraser River. Vancouver Island was established in 1843; British Columbia, in 1858. They were briefly united as British Columbia in 1866, then joined Confederation in 1871. Douglas was Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Victoria, 1840-1858, and Governor of Vancouver Island 1851-1864.

[4] The British Colonist, 5 August 1864, p 2 (hereafter cited as Colonist.); Terry Reksten, Rattenbury, Victoria: Sono Nis, 1978, p. 55. Edmund Verney noted that Mrs. Cary was “distantly related to James Douglas” (Vancouver Island Letters 1862-1865, Vancouver: UBC Press, 1994, p. 75), so a nepotistic appointment may have occurred or high-placed HBC officers in London may have met the young barrister or have heard of his talents. Working in Victoria, however, Cary, although loyal to Douglas, did not always seek to further the interests of the HBC. See for example, the suit between him and the Company, Journals of the Colonial Legislatures of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1851-1871 (ed. James E. Hendrickson), Victoria: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1980, 29 April 1864, vol. 1, p. 126. (Hereafter cited as Journals.)

[5] BCARS: Colonial Correspondence, Cary to Colonial Secretary Young, 12 March 1864, Microfilm B01313, File 275.

[6] Colonist, 29 December 1859, p. 2.

[7] Helmcken, Reminiscences, p. 176.

[8] Colonist, 21 May 1864, 2; 13 June 1864, p. 2.

[9] Colonist, 23 February 1864, p. 3.

[10] Henry Maynard Ball, Journal, 8 September 1864; BCARS MS-0750.

[11] Colonist, 14 September 1866, p. 3.

[12] The Gentlemen’s Magazine and Historical Review, vol. II, August 1866, 280; www.hathitrust.org.

[13] James E. Hendrickson, “Cary, George Hunter,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/ Université Laval, 2003, http”//www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cary_george_hunter_9E.html, accessed September 24, 2017.

[14] Helmcken, Reminiscences, p. 177.

[15] Burnaby, Land of Promise, p. 105; Verney, Letters, p. 105; James E. Hendrickson, “Cary, George Hunter,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9; Woodcock, Amor de Cosmos. Journalist and Reformer, Toronto: Oxford, 1875, p. 53.

[16] Helmcken, Reminiscences, 176; Ball, Journal, 28 August and 12 September 1864. When the Carys left for England, Ball empathized with Mrs. Cary: “poor Nelly.” (Journal, 21-September-1 October 1865).

[17] Farwell, Diary, 27 March, 20 November, 3 December, 1864. Farwell was well-connected in England. Richard Malins, who was acquainted with Sir Hugh Cairns, and who had probably recommended Cary for the colonial position, had married Susannah Farwell, daughter of Reverend Arthur Farwell. Farwell received letters from “Aunt Susan” and was occasionally in correspondence with “Uncle Richard.” Farwell himself was probably recommended to Cary by Malins. (Diary, 26 March 1864) Cary himself wrote to Malins in 1864 (Diary, 6 November 1864.)

[18] Farwell, Diary 1 July 1864; 16 September 1865.

[19] Quoted in Robin Ward, Echoes of Empire. Victoria and Its Remarkable Buildings, Madeira Park: Harbour, 1996, p. 266.

[20] Helmcken, Reminiscences, p. 177.

[21] Colonist, 21 July 1860, p. 3.

[22] Colonist 17 May 1864, p. 3; Colonist, 22 July 1865, p. 3. David Higgins, a journalist who may have witnessed this eruption, wrote that, during Cary’s outburst, his “wig sailed across the courtroom . . .” (D.W. Higgins, Passing of a Race and More Tales of Western Life, Toronto: Briggs, 1905, p. 62.)

[23] Colonist, 22 July 1865, p. 3. As editor of the Daily British Colonist, De Cosmos wasted no opportunity to criticize most of Cary’s legislation, such as his constructive land reform. The Colonist’s reportage, therefore, is not entirely objective.

[24] Burnaby, Land of Promise, p. 105.

[25] Farwell, Diary, 16 September 1865.

[26] Crease Papers, BCARS, Reel AO819, Box 5, File 15, 16 June 1865.

[27] Ball, Journal, 16 April 1865.

[28] See Richard Mackie, The Wilderness Profound: Victorian Life on the Gulf of Georgia, Victoria: Sono Nis, 2002, p. 43.

[29] Mark Girouard, Life in the English Country House. A Social and Architectural History, New Haven: Yale, 1978, pp. 2 and 3.

[30] Robert H. Hubbard, Ample Mansions. The Pre-Confederation Government Houses in the Provinces, Ottawa: University of Ottawa. 1977, p. 137; This Old House. Victoria’s Heritage Neighbourhoods, Victoria: Victoria Heritage Foundation, 2007, Vol. 3, p. 167.

[31] Colonist, 5 August 1864, p. 2.

[32] Colonist, 20 April 1861, p. 2.

[33] In this way, he tried to refute his opponents’ claims that he had been the Company’s appointee. Later, at a public meeting in Victoria, he averred that the Company “had robbed every lot-holder in the city….” (Colonist, 11 February, 1865, p. 3.)

[34] Greg Taylor, The Law of the Land. The Advent of the Torrens System in Canada, Toronto: University of Toronto 2008, p. 25. This system originated in the colony of South Australia.

[35] Colonist, 1 October 1863, p. 3.

[36] Colonist, 8 June 1864, p. 3; 10 June 1864, p. 3; James Robert Anderson Memoirs, MS 1912, Box 8, File 8. (BCARS: British Columbia Archives)

[37] Colonist, 5 August 1864, p. 2.

[38] Colonist, 14 January 1861, p. 3.

[39] Executive Council Minutes, 22 August 1864, GR-1223, vol. I; BCARS, GR-1223.

[40] Journals, Vol. 1, p. 142.

[41] Colonist, 23 August 1864, 3; British Columbian, 24 August, 1864, 3. The Victoria Evening Express offered simply a three-line notice, without comment. (22 August 1864, p. 3.)

[42] Executive Council Minutes, vol. I, 10 October 1864; BCARS GR-1223

[43] Colonist, 23 and 9 October 1860, pp. 2 and 2. David Babington Ring, Dublin-born, came to Victoria in 1859. Also an MLA and a barrister, he became acting Attorney-General during Cary’s absence in 1863.

[44] Colonist, 30 April 1861, p. 2. Cochrane [1827-1867] was a local politician and engineer.

[45] Tom Swanky. The True Story of Canada’s War of Extermination on the Pacific. Burnaby; Dragon Heart, 2012; and The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory. Surrey: Dragon Heart, 2016.

[46] Ball, Journal, 12 September 1864.

[47] Farwell, Diary, 21 April 1864.

[48] All the quotations here are from the Cariboo Sentinel BCARS MS-0676.4.11, June 1863 to November 1865.

[49] Colonist, 30 July 1863, p. 3.

[50] “Fifty Years Ago,” Colonist, 24 September 1916, p. 4.

[51] Farwell, Diary, 12 April 1864.

[52] Victoria Gazette, 17 September 1859, quoted in James E. Hendrickson, “Cary, George Hunter, Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

[53] Colonial Correspondence, 13 June 1860, BCARS Microfilm B01313, Files 175 and 275; Colonist, 21 February 1860, p. 2.

[54] Colonist, 4 March 1861, p. 2.

[55] Colonist, 4 March 1881, p. 2.

[56] Several Messrs. Wren appear in the 1865 newspapers, but why Cary should be upset with one of them is not clear.

[57] Farwell, Diary, 14 and 16 September 1865.

[58] Farwell, Diary, 21 and 25 September 1865.

[59] Gentleman’s Magazine, 16 August 1866, p. 280.

[60] Hendrickson, “George Hunter Cary,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9.

[61] Gentleman’s Magazine, 16 August 1866, 280. The English Law Times repeated this accolade; quoted in Greg Taylor, The Law of the Land, 684.)

[62] Colonist, 4 March 1881, p. 2.

One comment on “#411 The boy Attorney-General of B.C.”

Comments are closed.