#410 Journey to Fernie

Ordinary Strangers

by Bill Stenson

Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue Publishing, 2018

$23.95 / 9781896949710

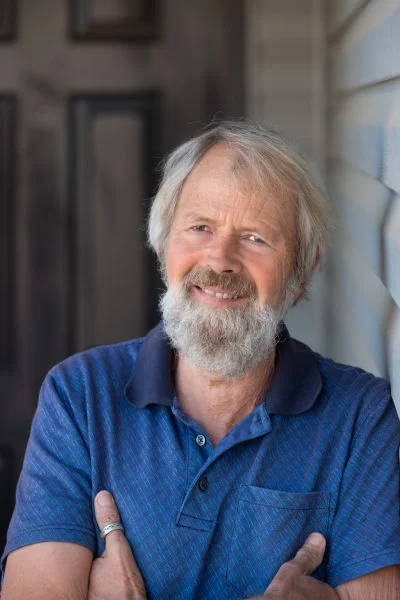

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

First published October 30th, 2018

*

The title is the key. This is a novel about the ordinary, yes, but also about people who are, in many different ways, “strangers:” within the first few pages an “ordinary” couple virtually sleep walks into abducting a child. The rest of the novel is superficially commonplace — after all, what could be more ordinary than two parents raising a child to adulthood? Though they may be ordinary to each other, however, the characters are also, in many ways, strangers — to themselves, to each other, and to the reader.

The title is the key. This is a novel about the ordinary, yes, but also about people who are, in many different ways, “strangers:” within the first few pages an “ordinary” couple virtually sleep walks into abducting a child. The rest of the novel is superficially commonplace — after all, what could be more ordinary than two parents raising a child to adulthood? Though they may be ordinary to each other, however, the characters are also, in many ways, strangers — to themselves, to each other, and to the reader.

Equally, though, the novel is about ordinary strangeness — the everyday, yes, but also the deeply strange, sometimes dark, underbelly of the mundane.

First, the ordinary.

The time is ordinary, the location is ordinary, the everyday lives are ordinary. Set mostly in the 70s and early 80s, the entire world has the faded colours of a film of that era. Some readers will find in it an appealing evocation of a period of Expo 86, Mulroney politics, and — most iconically for this book — the VCR. Even so, author Bill Stenson has chosen to use the familiarity of the retro time period mostly for atmosphere, not as an opportunity to penetrate the zeitgeist. Conversations about, for example, the scandal surrounding televangelist Jimmy Baker, flavour the time-soup, but little more.

The time is ordinary, the location is ordinary, the everyday lives are ordinary. Set mostly in the 70s and early 80s, the entire world has the faded colours of a film of that era. Some readers will find in it an appealing evocation of a period of Expo 86, Mulroney politics, and — most iconically for this book — the VCR. Even so, author Bill Stenson has chosen to use the familiarity of the retro time period mostly for atmosphere, not as an opportunity to penetrate the zeitgeist. Conversations about, for example, the scandal surrounding televangelist Jimmy Baker, flavour the time-soup, but little more.

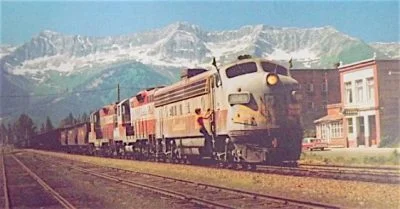

Likewise, the location. In many ways, the novel works squarely within the tradition of those “democratized” Canadian novels based in the world of small town commonfolk. Certain features of the selected town, Fernie, the cemetery, the river, and especially the mountain surroundings and the Kaiser coal mine, are evoked just enough to act as reminders that this is a specific town with specific characteristics. The author, though, doesn’t try to do for Fernie what, most famously in CanLit perhaps, Margaret Laurence did for the (fictional) Manawaka. The character or spirit of the town is not made to feel colourful: rather it is, importantly we feel, ordinary.

The spare writing style complements the location and period. Language is direct and un-fussed. This is not the writing of a novelist interested in inventive turns of phrase, richly cadenced syntax or delicately acid ironies. When they come, the rare striking sentences jump off the page. “It was the season when all the barbs that had snagged evidence of Sage Howard living in the house became most evident.” “Such days, flirting with an imbecile world seemed liberating.” Sentences like this suggest what the narrative voice could be, but generally avoids.

In their most general outlines at least, the characters are also unexceptional. Della, the mother of the abducted child, babysits; and little more. Sage, the husband, works his way slowly up the ranks in the coal mine, smokes pot, and fishes. Stacey, the child, suggestions of an Aspergers/autistic personality aside, goes to school, spends time with a few friends, and passes with little drama most (not all) of the usual mileposts of growing up.

The second rung of characters is, in some ways more colourful, almost to the point of being Dickensian: neighbour Molly the Nose is exactly that, repeatedly and relentlessly. Her husband, Hart, obsesses about the Wild West, repeatedly and relentlessly. Della’s long-lost (half) sister, Sadie, jets in from California, and does little to dispel her sister’s claim that she is a good time gal. Memorably, though, all these characters are good-hearted, very much diamonds in the rough.

Here, though, we have to pause. Character, more than any other aspect of the novel, goes far beyond the ordinary. From the outset it is clear that with Stenson we are in the hands of a writer unusual in his approach to character. In many ways, in fact, he makes his characters “strangers” to his readers. First, he avoids almost entirely providing observations from a narrator’s perspective. We are told little about the personalities of the chief characters, about their relationships, or even about phases of their lives. In many ways, Stenson’s approach seems more that of a screenwriter than of a conventional novelist.

Take Della. Rather than imbue her with a richly complex inner life, one in which his readers can track her feelings and thoughts, Stenson makes her both stolid and solid — a kind of literary version of one of those monumental, opaque women in a Picasso painting from the 1920s. Right from the beginning, he excludes us from her thoughts and feelings, even as she abducts the young child. Throughout her life, though, she reveals herself to us only through occasional diary entries — even-toned and almost muffled. Even her final sorrows the author allows us to experience only from afar.

Stacey, whose growth to maturity defines the shape of the novel, is likewise given an inner life glimpsed only fitfully. Rarely does he tell us what she is thinking (a memorable exception being her wonderfully odd child-thoughts on vegetables: “That was the problem with vegetables. They grew in dirt and came out dirty and needed to be thoroughly cleaned.”). He does vividly show her reacting to childhood events, (strikingly, in running away from kindergarten), but, until she is in high school he makes few narrative sorties into her thoughts or feelings.

Even then, and when she reacts to events like being sexually assaulted, Stenson creates the impression he is filming her emotional reactions, recording her words, rather than penetrating her mind. Although, by the end of the novel, the author positions her to be the central character, it is only during the last few pages that he reveals directly what she is thinking and feeling, and, even then, in a tightly packaged, purposeful way: “She had assimilated everything her mother had written in her diaries and most of it she accepted.”

With Sage — the most psychologically complex character in the novel and, by far the most colourful — Stenson’s approach is somewhat different. Of his restlessness, self-doubting eagerness for experience, enthusiasms and drives, we are told a great deal. At one point, for example, he observes, “Sage knew he had holes in his moral fibre. He always felt dissatisfied and could never stick to one thing.” The central character in the first part of the novel, this pot-smoking, mercurial character works his way through different jobs in the coal mine, engages in risky money-making ventures, becomes an obsessive fisherman, and even has an affair with a bar maid. Even with Sage, however, as we discover, a great deal of what drives him is also withheld. Particularly when his sexual drives take over, like a stranger he is almost beyond our ken. And, surprisingly, during the last part of the novel, he becomes largely a cypher, viewed entirely from outside.

With this cinematic technique that dominates his narrative methods, Stenson clearly has some hard choices to make in choosing his storyline. In fact, it is here, in focusing not on the thoughts of his characters, but their actions, that his melding of the ordinary and the strange makes its most distinctive impact. Arguably, chief amongst all Stenson’s creative strengths is his ability to invent quietly quirky, sometimes playful, scenes. In one of the only detailed expositions of her early childhood, for example, we read about Stacey and her childhood friend Tommy experimenting in drinking Kool-Aid and fizzies in order to produce cascades of burps. Indeed.

Such events demonstrate strong powers of invention — and a suggestion of human unpredictability, even strangeness. At one point, more idiosyncratically, Hart, the neighbour, steals a rented horse from distant Bull River and, with little explanation and fewer consequences, rides it over the mountains to his own back yard. The police are bemused but they (and the reader) aren’t quite sure what to make of the event.

Indeed, rather than producing a fluid sequence of causally inter-related acts, Stenson constructs his novel as a series of such side channels and back-eddies. His is not a world of plot-sequence, where an event sketched at one point necessarily links to another. Rather, in Stenson’s world, events are often almost discreet, echoing only faintly in the rest of the novel. In one of the mostly scrupulously detailed, but odd, scenes in the book, Della visits a man she has met only a few times, Oli Hendricks, a lonely widower and obsessive stamp collector. From the colour of the sofa to peculiarities of a postage stamp from Mauritius, Stenson brings the scene sharply alive — and then lets it drift away, like a half memory.

Even Sage’s pot-selling scheme to raise money for his house begins as a suspenseful plot line — and then simply stops. It is only later we deduce he actually did earn enough for his house.

Stenson’s ability to give the ordinary a sense of the odd or quirky, but to do so quietly, without fanfare or plot consequences, is nowhere more evident than in his treatment of sexual behaviour. Though not even remotely “graphic,” his handling of sexual behaviour repeatedly backfoots his readers. At one end of the spectrum is the scene he sets up so that we fully expect at least a minor flurry of sexual infidelity. What we get, though, however emotionally rich, is not even remotely that. His depiction of Sage’s affair with Selma, the bar maid, is somehow also off-centre, beginning and ending almost like an afterthought.

Likewise, Stenson’s depictions of a coolly choreographed first sexual experience at one point and, at another, of a mentally challenged man’s stalking and exhibitionist assault are typically low key — and inconsequential. A case of (almost) incestuous sexual predatory behaviour, and a subsequent fumbled and confused sexual assault pave the way for, later, the psychological climax of the novel, a deeply odd act of sex performed with the sole intent of tormenting a witness to the act.

In spite of its episodic and unpredictable nature, though, the novel’s main narrative arc and chief “suspense” unsurprisingly centre on the much-postponed revelation of Stacey’s abduction and her subsequent search for long lost parents. Even that storyline, though, is askew and unsensational: few readers are likely to anticipate what actually happens, but it is the kind of thing that does happen in Stenson’s oddly ordinary world. And, many will feel, their own.

Admittedly, the novel largely ends a little “novelistically,” its big events precipitated not by human will but by lightning bolts from above, a pair of sad and saddening deus ex machinas. Likewise, even though the major relationship of the novel’s latter part, that between Stacey and Sage, is “novelistically” resolved — it is, as we might expect in the world of this novel, happens in a greyed and nuanced manner.

In the end, like any novel covering many years, from births to deaths, this one leaves the reader with a kind of matter of fact melancholy. Can we conclude anything about “life,” though, from our experience? — that it is full of quiet desperation? that it contains little, nameless unremembered acts of kindness and love? that all our yesterdays lead the way to dusty death? that we are such stuff as dreams are made on?

Like most clear-eyed novels, it suggests – suggests — all of these. Most centrally, though, it reminds us that “life,” even ordinary life, has its own kind of strangeness, that even ordinary people are, fundamentally, strangers.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Theo is the author and illustrator of popular guide, travel, and hiking books including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island — Volume 1: Victoria to Nanaimo, and Volume 2: Nanaimo North to Strathcona Park (Rocky Mountain Books, both published in 2018 and reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen in The Ormsby Review no. 384, September 25, 2018). He has also written a Kindle book, When Baby Boomers Retire: Getting the Full Scoop. You can learn more about him from his website. Theo lives at Nanoose Bay.

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Theo is the author and illustrator of popular guide, travel, and hiking books including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island — Volume 1: Victoria to Nanaimo, and Volume 2: Nanaimo North to Strathcona Park (Rocky Mountain Books, both published in 2018 and reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen in The Ormsby Review no. 384, September 25, 2018). He has also written a Kindle book, When Baby Boomers Retire: Getting the Full Scoop. You can learn more about him from his website. Theo lives at Nanoose Bay.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

2 comments on “#410 Journey to Fernie”

Comments are closed.